The Land

When Ban Gu 班固 (32–92 CE) set out to write the History of Han (Hanshu 漢書), he planned a chapter titled “Treatise on Geography” (Dili zhi 地理志). He began by quoting legends about the earliest period of history known at that time, the era of the Yellow Emperor. It was a favorite practice of the authors of the Han dynasty, and, for that matter, of most of Chinese imperial history, to begin a treatise by quoting from ancient sources. The idea of antiquity seemed to have an authenticating effect, in most cases, rendering support and giving authority to what the author was about to write and argue.Footnote 1 Ban Gu was no exception:

The Yellow Emperor invented ships and wagons to assist with travelling so that people were able to move all over the country. He set up institutions across ten thousand li and drew lines to divide the provinces, and this resulted in ten thousand states, each being one hundred li square. This is why the Book of Change (Yijing 易經) states, “the former king established ten thousand states, and formed an alliance with the vassals,” and the Book of Documents (Shujing 書經) states, “[the Yellow Emperor worked] to harmonize the ten thousand states.” During Emperor Yao’s time there was a flood that flowed over the mountains and hills and separated the country into twelve provinces, and Yu was assigned to manage the flood. When the flood was under control, he re-divided the state into nine provinces, established the five levels of officials and instituted the taxation system.Footnote 2

As one follows the pages of the “Treatise on Geography” further, it is difficult not to get the impression that Ban Gu was actually writing about the historical evolution of the administrative units of the state; even the statistics about the households and residents of each of those units were all recorded. For example,

The Commandery of Hongnong, established in year four of Yuanding era (113 BCE) of Emperor Wu. It was known as Youdui by Wang Mang’s time. It has 118,091 households, with a population of 475,954. There is an office of iron production at Minchi. There are 11 counties: Hongnong County, formerly the Hangu Pass. Mount Ya presides over Xiagu, from which the River Zhu flows northward into the Yellow River; Lushi county, with the Xionger mountain to the east, where the River Yi flows towards the northeast and enters the River Luo, passes by one commandery and continues for 450 li. There is also the River Yu that flows southward until it enters the River Mian at Shunyang…Footnote 3

The geographic regions that he described in the “Treatise on Geography” encompassed most of the territory of the modern state of China, except for the Northeastern Provinces, Inner Mongolia to the north, Xinjiang and Qinghai to the west, and Tibet to the southwest. In a word, the world known to him as belonging to the rule of the Han regime roughly corresponded to the area that people lived in throughout later Chinese history. It is quite impressive that he was able to collect this detailed geographic information, although his position as the Director of the Royal Archives (Lantai lingshi 蘭台令史), did give him access to some of the most important documents and maps pertaining to the operation of the government. But why did he want to write this treatise, and to what purpose? Ban Gu’s main interest was, of course, not only the geography of the country, but also the entire history of the Former Han. It is nevertheless remarkable that he should have included such a chapter in his History, which strongly suggests that there was an interest in collecting the kind of information that could be useful in providing a bird’s eye view of the entire empire for people with a managerial mindset. The fact that such information was available at all, moreover, presupposes a society in which records of a massive scale were collected and archived on a regular basis by certain government agencies such as the Royal Archives that Ban Gu worked for. The recent discovery of a set of statistics concerning personnel and armory that was supposedly part of the annual report sent to the central government from the Donghai Commandery may corroborate this point.Footnote 4 Therefore, let not the 2,000 years between his time and ours veil the fact that at the beginning of its imperial history China was already a highly bureaucratized state, with managerially minded intellectuals who constituted the backbone of the government.Footnote 5 We shall have ample opportunity to witness this character throughout the study.

Ban Gu was particularly interested in describing the historical evolution of the hydraulic system of the land, as the taming of the flood water by the legendary King Yu was considered in most early sources a decisive episode and a common memory of ancient Chinese history. Unlike the biblical flood that was sent down by God, in China the flood was a natural disaster that people were expected to conquer. Since the management of water was essential to agriculture, the issues of flood and drought were constant and serious factors that affected the livelihoods of myriads of farmers, and ultimately everyone in the country. According to legend, when Shun was emperor, an enormous flood spread throughout the land. Shun first entrusted Yu’s father, Gun, with the task of managing the flood. Nine years on, he still had not completed the task, as he was using the strategy of damming up the water, which was ineffective. Shun thereupon appointed Yu to continue the work. Fearful of another failure in completing the job, he put all his efforts into the task, did not return home for thirteen years, and finally succeeded in channeling the flood into the ocean, thereby managing to save the ravaged land. Yu’s son, Qi, succeeded him and became the first sovereign of the Xia dynasty, the chronicle of which was preserved in the Records of the Grand Scribe (Shiji 史記) by the Western Han dynasty historian Sima Qian (司馬遷 c. 140–86 BCE). Some modern scholars view the story as wholly fictional and see Yu as no more than a sort of cultural hero who epitomized the ancient memory of an era of natural disasters.Footnote 6

Certainly, the legendary history of early China began earlier than the reign of King Yu, as the interest in historical writing and in managing the state also preceded Ban Gu. Sima Qian gave an account of the early history of China in the early chapters of his Records of the Grand Scribe by piecing together stories about the rulers of the remote past, beginning with the Yellow Emperor; continuing up to the sage rulers Yao, Shun, and Yu; down to the kings of the Shang and Zhou dynasties. This chronological account of the succession of the rulers is, of course, not to be taken literally, as we know from modern archaeological studies that during the period between 3000 and 300 BCE (roughly before the unification of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE), the East Asian subcontinent was never ruled by a single regime, despite the claims of the dominion of the Shang and the Zhou. The vastness of the land itself and the diverse geographical features speak forcefully of the natural division of the land into smaller units.

Sima Qian was well aware of this situation, which he described in the “Treatise on Food and Merchandise” (Huozhi liezhuan 貨殖列傳) in his Records of the Grand Scribe:

The area within the Pass, from the Qian and Yong rivers east to the Yellow River and Mount Hua, is a region of rich and fertile fields stretching for a thousand li. Judging from the tribute exacted by Emperor Shun and the rulers of the Hsia [Xia] dynasty, these were already considered to be among the finest fields available at that time … In fact, the people of this region still retain traces of the customs they learned under these ancient rulers. They are fond of agriculture, raise the five grains, take good care of their fields, and regard any wrongdoing as a serious matter.

Later, Dukes Wen and Mu of Qin established the capital of their state at Yong, which was on the main route for goods being brought out of both Long and Shu and was a center for merchants. Dukes Xian and Xiao moved the Qin capital to the city of Yue … It, too, was a center for great merchants. Kings Wu and Zhou established their capital at Xianyang, and it was this site that the Han took over and used for their own capital, Chang’an. People poured in from all parts of the empire to congregate in the towns established at the imperial tombs around Chang’an, converging on the capital like the spokes of a wheel. The land area is small with a large population, and therefore the people have become ever more sophisticated and ingenious and have turned to secondary occupations such as trade to make a living.Footnote 7

Sima Qian’s account could be seen as a kind of “cultural geography” in the modern sense; he was interested in the interactions between various factors such as the geographic features of the land, the resources of each area, the character and temperament of the people, and the local customs. Again, from a different angle, he demonstrated a kind of managerial interest in describing the composition of various sectors of the state. It was his way of giving a historical explanation to the social and cultural development of the country by observing the multifarious characteristics of different regions. Such an interest, therefore, received further development in Ban Gu’s “Treatise on Geography,” where cultural geography can be seen in the account of administrative registers.

The Rivers

In looking at a map of China, it is clear that the land of the East Asian subcontinent has been carved out by two river systems – the Yellow River and the Yangzi River – into several smaller areas.Footnote 8 The Yellow River to the north was known to the people in ancient times simply as “The River.” Its power to give life but also bring about destruction was likely the reason for its divine status in the belief systems of these ancient peoples. In the Shang dynasty oracle bone inscriptions, the river was one of the deities to which the Shang king offered sacrifices and prayed for blessings.Footnote 9

The famous Tang dynasty poet Li Bai (711–762 CE) opens his most renowned poem, “Wine Drinking (Jiang jinjiu 將進酒),” with these lines:Footnote 10

Usually readers of this poem appreciated the use of the constant flow of the Yellow River as an allusion to the passing of time. Less noticed is that the Yellow River was, by Li Bai’s time, no less a source of life than it was in the Shang dynasty. The phrase “falling from the sky” was not only a literary expression to describe its source, but also carried some implicit reference to its divine status. It originates in the high mountains of modern Qinghai Province, rushing down from an elevation of 4,800 meters toward the eastern sea for a distance of 5,460 kilometers. Along the water course, areas suitable for agriculture were formed, notably around the middle reaches of the area of the Wei River (a tributary of the Yellow River) basin, where the Han capital city Chang’an (modern Xi’an) was located, and further downstream to the east, the Central Plain area, where the city of Luoyang had been the center of political and economic power since the time of the Zhou.

Owing to the lower elevation of the plain and the high sedimentation level of the river, the river bed below its middle reaches actually rose higher than the plain through centuries of sedimentation; thus the river was prone to bursting its banks and causing flooding from time to time. In the two and half millennia of recorded history, the Yellow River flooded its area more than 1,500 times and changed its course 26 times, which indicates that King Yu’s celebrated achievement was nowhere near a complete success.Footnote 11

In the ancient period, during the fourth and third millennia BCE, the average temperature of North China was a few degrees higher than it is in the modern era, and lush forests were part of the landscape. The loess plateau encircled by the Yellow River, which comprises present-day Shaanxi Province, was greener than in its present state and boasted abundant natural resources. It was allegedly through thousands of years of human development that the area lost its vegetation and became impoverished. The Wei River basin south of the loess plateau was nevertheless suitable for agriculture and, being encircled on all sides by mountains, was the power base of the Qin-Han and later the Tang Empires. A Western Han scholar, Jia Yi (200–168 BCE), once pointed out the strategic importance of this area:

The land of Qin was surrounded by mountains with rivers running through, and it was secured on four sides. Since the time of Duke Miu, until the First Emperor, there were more than twenty rulers who often were leaders of the vassals of Zhou. Could this mean that every generation of rulers was good? It was in fact due to the geographic superiority of the region.Footnote 12

Passing through the Hangu Pass (Hangu guan 函谷關) at the eastern end of the Wei River basin, therefore, the Yellow River faced no further obstacles to the east, and the entire Central Plain was practically the beneficiary – or the victim – of the river system. The city of Luoyang was the power center, located at a strategic position west of the Central Plain, flanked on both sides by mountain ranges, taking command of the land to the east. It was the capital of the Eastern Zhou and Eastern Han, and of many later dynasties.

The Yangzi River is the longest river in China, also originating, as does the Yellow River, in the high mountains of Qinghai Province. To the ancients, it was known simply as the “Jiang” (river), a name probably derived from a language of the ancient Austroasiatic people.Footnote 13 Modern Chinese refer to it as the Long River (Changjiang 長江). Its 6,300-kilometer journey across the middle of the East Asian subcontinent passes through some of its most fertile agricultural regions, with no fewer dramatic changes of geographical characteristics than the Yellow River. Before the Yangzi broke through the Three Gorges it nurtured the Sichuan basin, with its ancient name Shu, which was also the center of a mysterious bronze culture, contemporary with the mid-Shang dynasty, known today as the Sanxingdui 三星堆 culture. Following the current, in the middle reaches, early agricultural societies such as Daxi 大溪 (c. 4400–3300 BCE) and Qujialing 屈家嶺 (c. 2500–2400 BCE) became prosperous, while in the lower reaches, the Hemudu 河姆渡 and Liangch良渚 cultures flourished during the fifth millennium BCE.Footnote 14

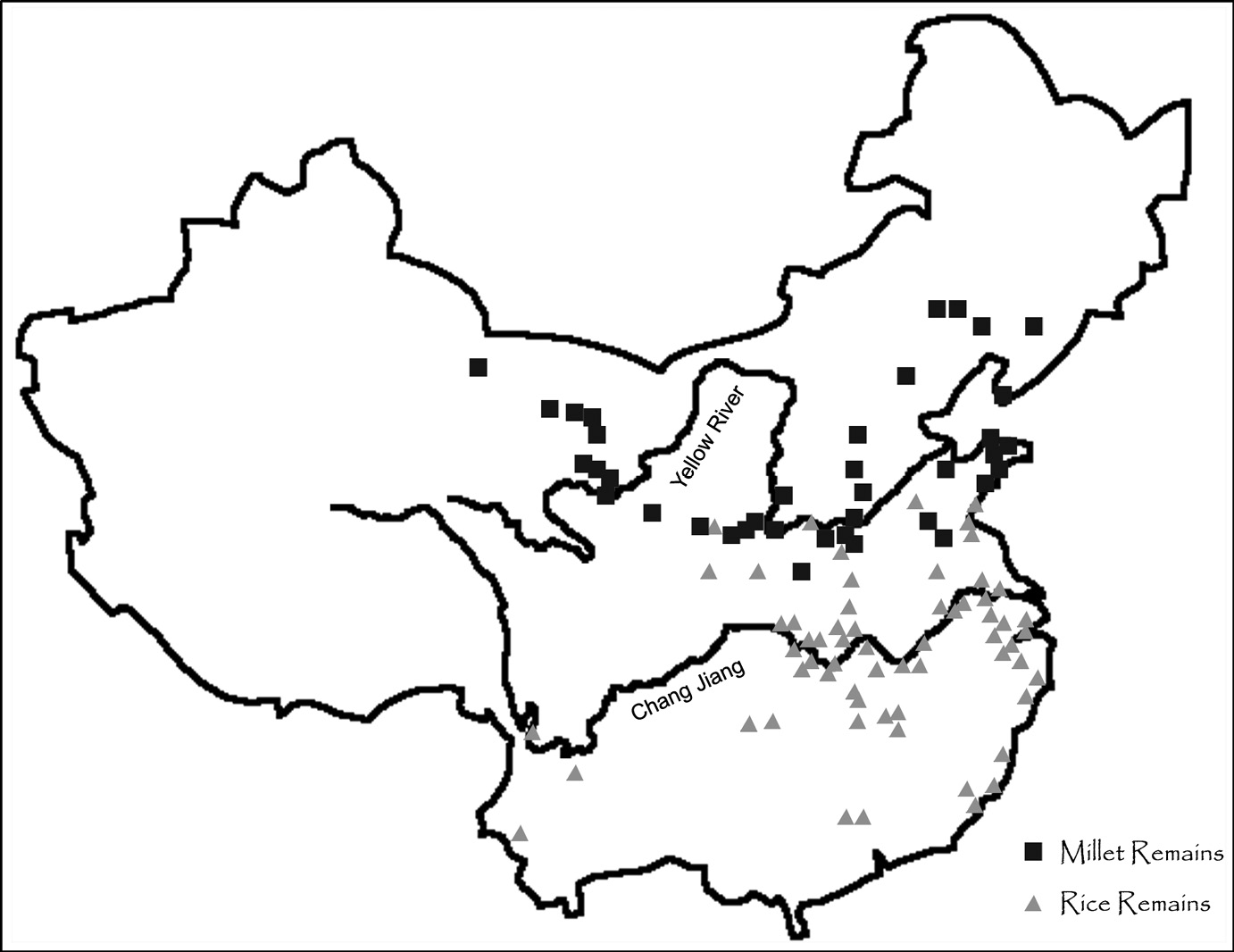

In general, the major crop of North China, irrigated by the Yellow River system, was millet, while the major crop of the area irrigated by the Yangzi River was rice, at least from the late Neolithic period. In between the two river systems was an area where rice and millet cultivations overlapped, as the region was a transitional zone from subtropical climate, which was more suitable for rice cultivation, to temperate weather, which was more suitable for millet (Fig. 1).Footnote 15 Climatic studies show that between 6000 and 1000 BCE the North China Plain experienced a period of relatively warm weather, during which there were greater numbers of subtropical plants and animals in the area. The onset of cooler climate after 1000 BCE led to a division between the temperate and the subtropical zones that remains to the present day.Footnote 16

1. The distribution of rice and millet remains in the rice and millet blended zone in the Neolithic Age.

Farmers in both areas cultivated a variety of plants for food in addition to the major staples of millet and rice. By the beginning of recorded history, that is, the late Shang dynasty, domesticated animals included pigs, dogs, cattle, and goats and were a major meat source of these people, in addition, of course, to the abundance of game in the forests and fish in the rivers and lakes. In the south, that is, the Yangzi River Valley, buffalo were also domesticated (Fig. 2).

Shang

The earliest literate society in this part of the world, the Shang dynasty, with its last power center at Anyang, Henan Province, succeeded an earlier dynasty, the legendary Xia. Although still unidentified archaeologically, it is generally assumed that the Xia dynasty originated in the west, in Shanxi Province.Footnote 17

The early history of the Shang could be represented only by archaeological discoveries and the information preserved in the transmitted pre-Qin texts and the Records of the Grand Scribe of Sima Qian. So far the earliest Shang power center to be identified was the site at Yanshi (偃師), Henan. With a total area of 1.90 million square meters and well-built city wall, palace buildings, ordinary housing area, cemetery, pottery kilns, wells, as well as drainage pipes, the city of Yanshi marked the beginning of a powerful and well-organized state. As it is also close to the pre-Shang (possibly belonging to the legendary Xia dynasty) site of Erlitou 二里頭, which displays many similar material features, a reasonable assumption would be that the Yanshi site was a successor of Erlitou.Footnote 18 A little later than Yanshi was the site of Erligang 二里崗 at Zhengzhou 鄭州. With an increased area of 3.17 million square meters, this city shows improved design and consideration of the living environment.Footnote 19

Later sources mentioned that before choosing Anyang as the last capital, the Shang court had moved a number of times, indicating a certain unstable situation of the regime, either politically or economically. Presumably, as the most powerful and culturally sophisticated state from the multicentered tribal system at the end of the Neolithic period, the Shang had acted as a kind of overlord of a loose confederation of smaller states, known collectively as the “Four Lands” (situ 四土) in the oracle bone inscriptions, which would bring tribute to the Shang court, and which would form a buffer zone surrounding the Shang. Punitive warfare with certain tribes or chiefdoms, notably the Guifang 鬼方 and Tufang 土方, was often mentioned in the oracle bone inscriptions, lending some weight to the assumption that the Shang had a certain power over these tribal states.Footnote 20

During the late Shang period when the capital was at Anyang, more than fifty independent states mentioned in the oracle inscriptions were scattered around the Shang capital, and more than forty small townships were under the rule of the Shang king. One of the largest independent states not mentioned by the oracle bone inscriptions was the early to middle Shang state, perhaps the early capital of the state of Shu (蜀), at Sanxingdui, modern Guanghan, Sichuan Province. The extraordinary bronze objects, including the huge masks, the bronze tree, and the statue, indicate a culture that was powerful, vibrant, and although related, quite different from the Shang culture.

Much about this culture is still covered in a fog of mystery. The fact that this state could have the control of such enormous bronze industry indicates that one should reevaluate the status of the Shang among the contemporary power structures, and view it as one of the main cultural centers, though perhaps better known to later generations because of the use of an effective writing system that allowed the passing down of knowledge and information that privileged the owner of the writings.

It should be clear that, although a dominant political power with sophisticated bronze industry and working bureaucracy, the Shang was not the sole player in the land, and many sizable and independent communities, whether under the cultural influence of the Shang or not, followed their own course of development. One of these states, the Zhou, eventually accumulated enough strength to challenge the leadership of Shang, and was able to replace it.

One conspicuous feature of the Shang in terms of possible communication with the outside world was the funerary pits of chariots and horses. It has been argued that the use of a horse and chariot came from the West, perhaps from the Near East through central Asia, since there was no trace of the use of a horse and chariot before early Shang. What can be certain is that the construction of a chariot involves the use of sophisticated bronze components that only the ruling elites who controlled the resources and production of bronze objects – including the ritual vessels and weapons and armor – could have afforded.Footnote 21

Bronze Culture

Ever since the excavation of the royal tombs of Shang at Anyang in the early twentieth century, the Shang bronze culture and oracle bone inscriptions have been at the center of scholarly attention, as these were the most prominent testimony to the achievements of the people who created this culture, and whose imprint on the later development of the Chinese culture was permanent. The royal cemetery at Anyang, with the huge royal tombs, the median tombs of the nobles, and the small tombs of the lesser officials, graphically shows the formation of a well-established complex society.

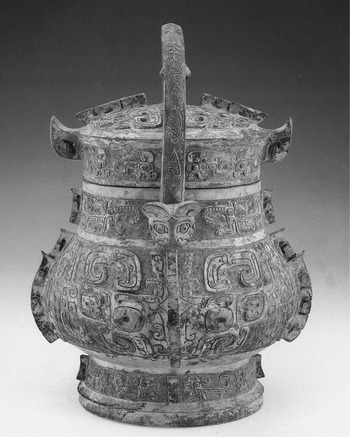

The bronze vessels found in the tombs and storage areas at Anyang and elsewhere, in various shapes and numbering in the thousands, and now often occupying a central position in museums around the world, testify to a refined ritual practice that at the same time was an expression of religious ideas, political order, economic power, aesthetic articulation, and technological innovation. They are not merely vessels for cooking and for making offerings to deities and ancestors; they are markers of political status, as the size and number of vessels in a burial chamber often correspond with the political status of the deceased. They also imply a well-established chain of resource appropriation and production management, as revealed by the discovery of casting workshops.Footnote 22 They are, furthermore, the embodiments of a special kind of aesthetic sentiment with highly refined casting technology, as shown by the ubiquitous and ever-changing taotie-animal (饕餮) style designs on the vessels (Fig. 3).Footnote 23

3. Bronze vessels with animal style designs.

The function of the bronze vessels, besides daily use at banquets and meals, was to contain food offerings at religious rituals. When food was cooked and the aroma rose upward to reach the spirits, the gazing eyes of the taotie on the container could have added a sense of intense expectation.Footnote 24 Such sensual but mute communication with the spirits, whether ancestral or divine, must have been supplemented by verbal communications such as prayers, songs, or spells. Yet what we do have are records of another form of communication with the spirits, the oracle bone inscriptions.

Divination

Being a form of divination, the Shang oracle bone records open a window for us to the spiritual world of the Shang people, albeit that of the ruling elites. This spiritual world, seen through the looking glass of divination, could be severely distorted when we gaze into it. Thus we need to pay extra attention to contextualize the information we gain from the divination records.Footnote 25

Divination exists in many cultures, under the basic assumption that there is a certain connection between worldly phenomena and future events. Through certain skills and knowledge in reading the signs, whether natural or manmade, one was expected to be able to interpret the meanings of these signs and thus discover the divine wills or future events. The divination records of the Shang preserved for us some of the questions, and therefore the concerns, of the Shang people regarding various aspects of their lives. Among the most commonly asked questions were those related to agricultural topics such as rainfall and harvest; warfare with foreign peoples; sacrificial ceremony for deities and ancestors; and even the personal health and well-being of the king or royal family members, concerning matters such as toothache, illness, or childbirth.

Divination could be an ambivalent pursuit. One wishes to know what the future holds, but also fears that the message will be inauspicious. The dilemma between “to divine or not to divine” must have troubled many who felt pressed to learn about the future. Thus the Shang diviners often cast their inquiries more than once, and as both positive and negative queries: Will it rain? Will it not rain? The answers that they received were then carved on the oracle bones after the queries.

Scholars have tried to explain the fact that some of the divination records contained only the questions but not the answers. Could these be a way of communicating with the divine power as a form of supplication rather than divination?Footnote 26 It seems that the “powers” to which the Shang diviners posed questions were never directly mentioned. We are thus unsure whether a question such as “Will it rain?” was addressed to the rain god or to another more powerful god who could order rainfall. We are still not certain if even questions such as “Will Di (i.e., the god on high) cause it to rain?” were addressed to Di directly, and not to some intermediate power or messenger, as the question was not addressed in the second person, such as “Will thou cause it to rain?” Thus although the act of divination is based on the assumption that there is a way to have access to the divine will, there might not be sufficient grounds to view the queries as a form of prayer.

The implication of divination may be elaborated further: since there is a connection between certain worldly signs and the future, there had to be an assumption that the future is already determined or prescribed, and, importantly, knowable. The fact that people also offered prayers and sacrifices to the deities implies that they hoped to manipulate the divine will and to change the prescribed future. As the deities could presumably change the fate of the people, knowing the future became important: one should keep the good prognostication, and try to change any inauspicious predictions. This, indeed, was a widely held conception in the ancient world.Footnote 27

What can be certain is that Di was a major deity who could command various natural phenomena such as rain, clouds, drought, and flood, as well as bestow a harvest and bless the king with land and victory.Footnote 28 It seems logical to see the lesser deities as obeying the command of the Di, much as subjects obeying the ruler in a secular court. If there were a pantheon, therefore, Di would be the presiding deity. The royal ancestors were sometimes said to be able to visit with Di, indicating that the Shang people regarded their deceased rulers as possessing a certain divine status and thus becoming objects of cult worship. Besides sacrificial rituals to the deities, ancestral temples and ritual offerings associated with the temples were often mentioned in the oracle bone inscriptions. This two-track ritual system, one for the deities and another for the royal ancestors, was followed by later ruling regimes and formed the basic structure of the Imperial Cult.

Food and Drink

The intensive care and effort put into the production of ceremonial food offerings can be seen not only in the variety of bronze vessels used in the rituals, but also in the treatises found in later texts such as the Book of Ceremonies (Yili 儀禮) and the Book of Rites (Liji 禮記).Footnote 29 Here it should be pointed out that we could probably treat the theoretical considerations of food offering of the Shang and Zhou as one continuous tradition. In this tradition, the major components of an august offering would usually include meat and alcoholic beverages, the produce of husbandry and agriculture.Footnote 30

Archaeological findings from the Shang period include the remains of such domesticated animals as cattle, goats, pigs, dogs, horses, and chickens. Wild game includes bear, fox, raccoon, tiger, leopard, elephant, hare, deer, boar, gazelle, buffalo, rhinoceros, monkey, and tapir. There were also various types of fish, turtles, and clams. The appearance of some of these creatures, which cannot be found in later records, indicates a warmer climate in North China during the second millennium BCE.

The staple diet consisted of millet, barley, wheat, sorghum, and rice, plus various fruits and vegetables. Alcoholic drink made of millet was known to the people far earlier than the records found in history indicate; thus only some legendary accounts are able to fill the void.Footnote 31 Since grape was not a native plant, grape wine was unknown to China until the Han dynasty. For convenience’s sake we use the term wine to refer to all kinds of alcoholic drink made from grain.

One of the major features of daily life was the way people sat and consumed their meals. Until the invention or importation of the idea of a chair into China, possibly with the coming of Buddhism in the years after the fall of the Han dynasty,Footnote 32 people sat on the ground, in the posture of either kneeling or squatting, or resembling a winnowing basket. The last posture, according to later sources, was considered rude in public places and could carry apotropaic meaning because of its sexual implication. Depending on the means available, a mat made of various kinds of fabric would serve as a sitting surface between the ground and the body. The vessels containing food would be put on the ground or on a low table. Although knives and spoons were used to help with cutting and scooping, in general food was taken by hand, since chopsticks, though found in late Shang tombs, were not used for eating until the Han dynasty.

As for cooking, ancient texts such as the Book of Rites mentioned a host of culinary terms, including various ways to barbeque meats; to use cooking pots to boil, steam, and fry; and to prepare food by marinating and making sauces using salt, wine, sweet (honey and malt) and sour (plum) ingredients, indicating that these people had developed a very mature and complicated food culture. It is true that although the Book of Rites dated probably to the Warring States period, the sophisticated way of food preparation contained in the text could have had a long history.Footnote 33 This attention to the culinary experience had a rather unusual impact on the development of religion and philosophy. The ancient Chinese authors were very much attracted to the idea of using culinary metaphors to convey all sorts of philosophical and religious ideas. Many of the important discourses on personal cultivation, wise governing, and human–divine interactions were cast in the thinking and vocabularies of culinary art.

For example, meat consumption, by virtue of its importance in the diet of the rich and noble in ritual sacrifices to the spirits, became the object of philosophical speculation. Whether, how, and when to consume meat were subjects of discussion for the ancient Chinese authors. This train of thought has much resonance in the life and teaching of Confucius. It has been argued that in the Confucian tradition, the attitudes toward food and food consumption are reflections of an accomplished gentleman’s appreciation of social hierarchy, ritual propriety, and moral integrity.Footnote 34 Yet one of the most famous metaphoric uses of culinary art is the story of the Cook Ding told by the Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi (莊子, c. 369–286 BCE). The story relates Cook Ding’s superlative skill at dissecting cattle, which stemmed from his thorough understanding of the animal’s anatomic structure. By recognizing how the cow’s muscles, sinews, and joints intertwined with each other and by perceiving the cavities between them, he was able to pass his cleaver through the cavities and dismantle the entire structure without ever hitting the bones. After nineteen years, as the story goes, his cleaver was still as sharp as one fresh from the grindstone.Footnote 35 Of course, Zhuangzi is not really talking about culinary art, but about the importance of searching and following the Way. Yet the use of this culinary art, in fact the basic art in any kitchen, as a metaphor for the achievement of supreme knowledge, indicates that culinary art occupied a particular position in the theoretical articulation of the author. It also expressed vividly his idea that the most exalted revelation of truth could be found in the most mundane situation. Similarly, Laozi’s terse one-liner, “governing a large state is like cooking a small fish,” is not about cooking, but about mastering the art of governance. Although one cannot assign a definite explanation to this sentence, it appears that the text does not suggest that cooking a small fish is an easy matter. On the contrary, since to cook a small fish properly takes delicate mingling of various ingredients and controlling the timing and temperature that only an experienced chef could have achieved, governing a large state is no less of a complicated and delicate matter that requires the mastering of the Dao, just like Cook Ding’s ability to follow the Dao in his art of dissecting the bull. This love of expressive use of culinary experience was understandably a sign of a prosperous society, in which a whole stratum of social elite was responsible for the nurturing of such a sophisticated taste.

Dress

Certainly, signs of opulence could be observed not only in delicate food and luxurious food vessels, but also in the style of dress. According to ancient legend, the queen of the Yellow Emperor, Leizu, invented the art of silk weaving. Silk fabrics were found as early as the Neolithic period. By the time of the Shang, silk was widely used by the upper classes, as weaving had become a mature craft. Six kinds of different weaving techniques are found in fragments from the tomb of Fuhao, the queen of Shang King Wuding. In all likelihood, for the common people, a cheaper material would be more practical. The use of flax fiber for weaving was also a long-established practice, and linen would be the main textile that people used to make garments. Although the Shang people also knew how to use wool and other fabrics, these were never the major garment materials. The few available examples of human figures from the Shang period show that the dresses that people wore were either a short dress with a lap from left to right or a join in the middle, plus a short skirt, or a long dress that fell beneath the knee. People usually walked bare-footed, but they were also known to wear shoes made of cloth or leather, sometimes with high soles made of wood to avoid the dampness on the ground.

Living Space

A way to avoid dampness, of course, is to build one’s residence higher, either on elevated ground or by making the ground higher. Long before the Shang dynasty, people had learned the technique of making pounded earthen platforms for building beds, houses, and palaces. The higher one’s social and political status, the higher the ground floor on which one’s residence was built. Taking the palace site no. 1 at Erlitou as an example, the entire area measured 108 × 101 meters, had a pounded earth ground base, and the main palace was built on a platform measuring 36 × 25 meters, about 3 meters high. The entire palace compound of the late Shang capital at Anyang was located on a piece of higher ground overlooking the nearby river Huan.

A salient feature of the Shang city was the city wall, a testimony of the conflict and warfare between various political powers. The wall of Yanshi measured 1,700 × 1,200 meters, with seven gates, checkerboard-like roads within the city, and a surrounding moat that protected the city. The city at Zhengzhou has a wall measuring 1,690 × 1,870 meters, with eleven gates, a palace area that occupies 380,000 square meters, and the largest building with a base measuring 65 × 13.5 meters.

The majority of the people, needless to say, lived in much smaller residences. Within the Anyang area, a house with a suite built above ground, about 30 square meters in size, would count as being rather comfortable and perhaps fit for the nobility. Next to this would be a half-underground single-room house measuring about 15 square meters, perhaps occupied by ordinary residents. The smallest houses would be an underground pit that was only large enough for a single person to reside in. No doubt this would be for people on the lowest scale of the social ladder. Conceivably, residences outside of the city in the countryside would be considerably larger, yet without the various support and conveniences that a city could have offered.

Zhou

According to ancient texts such as the Book of Poetry, the Zhou dynasty originated to the west of Shang, in the area of present-day Shaanxi and Shanxi area, and was a subordinate vassal of the Shang. Oracle bones discovered at the site of Zhouyuan, the ancient cultural center of Zhou, indicate a cultural background similar to that of the Shang. The early Zhou rulers, including the kings Wen, Wu, Cheng, Kang, and the legendary chief architect of Zhou ritual system, the Duke of Zhou (Zhougong 周公), were represented by later sources as consciously building a state institution based on ritual (li 禮) and music (yue 樂). They made a departure from the Shang custom of indulging in the belief in spiritual beings and opted for a more rational understanding of the workings of the world. Most importantly, the concept of the Mandate of Heaven was invented to account for the political transformation. The Mandate was seen as representing the moral principle of the supreme power, Heaven, which would be conferred on the rulers who exhibited high moral standards. According to this concept, in order to gain the Mandate, that is, the legitimacy to rule, the ruler had to act according to this moral principle. Thus any ruler who successfully secured political control of the state could claim that he had gained the Mandate of Heaven, because Heaven would bestow the Mandate only on rulers who were morally worthy of the position. Thus Heaven was seen as having a rational and moral will that distinguished the evil and the good. This concept of the Mandate would thus become the official position for generations of rulers to claim their legitimacy to be on the throne. The replacement of the Shang by the Zhou rulers, therefore, was interpreted by the Zhou as the shifting of the Mandate.Footnote 36

Yet what were the vices of the Shang that caused it to lose the Mandate? Understandably it was the Zhou rulers who supplied the answer. In a chapter entitled “Announcement about Drunkenness” in the Book of Documents (Shangshu 尚書), the newly established Zhou king attributed the fall of the Shang to their indulgence in wine drinking. It was the excessive consumption of alcohol that eroded morale and corrupted the entire ruling apparatus. Anyone who engaged in wine drinking, thus announced the apprehensive Zhou king, would be arrested and executed. The bad example that the Shang rulers set, though most likely a piece of Zhou political propaganda in support of the shifting of the Mandate, was remembered by later generations as a grim reminder for those in power to be aware of the destructive potential of alcohol. What is significant about the charges against the last Shang ruler is that they had identified a ruler’s personal moral character with the legitimacy of his political authority as well as his ability to govern. In other words, a person without virtue would not have the authority or the ability to rule, and vice versa, a person with virtue was commensurate with a person with the authority and ability to rule. This, although comparable to the Platonic philosopher king, is of course not true at all in reality. Yet the myth of virtue as equaling ability and legitimacy persisted henceforth as the enduring legacy of the Zhou political culture.

There is, of course, no use in speculating on whether the charges against the Shang rulers were historically true or not. The bronze objects excavated from the Zhou dynasty tombs contain a considerable number of wine vessels, which demonstrates that wine drinking was not at all prohibited in the Zhou. As demonstrated by various documents, it seems that the Zhou rulers did not and could not really forbid the use of alcoholic drinks either in public or in private lives. Thus the prohibition against the consumption of alcoholic drink was no more than lip service, moralistic advice that had no actual effect on the customs of society at large.

To ensure the success of the dynasty, the early Zhou rulers instituted a system of vassalage based on kinship ties. Sons and brothers of the king were given fiefdoms to rule as vassals. This assumption that kinship ties could guarantee strong political alliance, of course, proved only wishful thinking in reality.Footnote 37 From the beginning when the system was implemented, as the story has it, powerful brothers of the kings were not satisfied with being subjects of their siblings. Throughout the Zhou, therefore, peace and prosperity existed only when the ruler himself was capable of controlling the vassals. The benefit of support from the vassals grew ever slimmer as time went by, until the situation became uncontrollable under the corrupt King You (c. 795–771 BCE), when the vassals rebelled and overthrew the king and established another, King Ping (reigned 771–720 BCE), as the symbolic head of the state. This ruler moved the capital from Chang’an to Chengzhou (i.e., Luoyang). This move between Chang’an and Luoyang became a pattern of later dynastic transition: the Western Han established its capital at Chang’an, and the Eastern Han moved to Luoyang. The Tang dynasty, after the long confusion following the fall of the Eastern Han, again returned to Chang’an.

The Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE), that is, the period from the beginning of the Eastern Zhou when the capital was moved eastward to Luoyang, was a time when powerful vassal states took turns at playing leading roles by claiming their loyalty to the Zhou kings, while developing their own power sphere. At the time, numerous small vassals and independent tribes were scattered among the larger Central Plain states and were collectively known as the Hua/Xia, that is, the cultural descendants of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. It was a time when the Hua/Xia people (including the Zhou and their vassals) were engaged in conflicts and rapprochements with foreign tribes and states known as Rong, Yi, Man, and Di, which must have begun long before they were recorded in any written form, such as texts inscribed on the bronze vessels, or the Zuozhuan 左傳 (Commentary of Master Zuo), a historical commentary to the chronicle of Chunqiu 春秋, the Spring and Autumn Annals, attributed to the hand of Confucius.

The Zuozhuan was the first narrative account of the events of the Eastern Zhou or the Spring and Autumn period. Although certainly a literary representation of what could have happened instead of what really had happened, it was most probably partially based on state archives, in particular that of Lu, Confucius’s home state. It shows frequent political activities in the form of war and diplomacy, court intrigues, and marriage alliances, not only between the states, but also between the states and the non–Central Plain states, the so-called “Rong-Di barbarians.” For lack of other extant historical records for this period, the Zuozhuan became the major source of information. It was also one of the most favored literary texts in China, as generations of literati read and quoted from it, not only for the elegance of the writing, but also for the moral of the stories.Footnote 38

By the end of the period, most of the smaller states had been obliterated from the map, with only seven strong states left to continue their struggle for political supremacy. This Warring States period (476–221 BCE) saw a rapid change in the development of statecraft, the blooming of intellectual diversity, the progress of agriculture, the expansion of commercial activities, and the advancement of military technology.

This was also a time that a new medium of economic activities was needed to facilitate commercial exchange. Unlike the round coins invented in the Greek world, the earliest “currency” found in the Shang dynasty was made of cowry shells, indicating that sea shells during that time were regarded as something valuable and could serve as the medium of exchange. Subsequent forms of money produced after the Zhou were in the shapes of bronze spades, hoes, and knives, reminiscent of the time when these objects were valuable objects of daily use, and thus served as common media of exchange. Various kinds of money were issued by the states to facilitate the exchange of goods, although, expectedly, the lack of a common system and the knowledge of how currency functioned in an incipient market system made it difficult for the currency to actually become a convenient tool for commerce, not to mention the cumbersome shapes of coins (Fig. 4). It was only after the unification of the empire by the Qin state that a unified currency was issued by the government, so that a common means of exchange could be used by people everywhere. This attempt, however, was short lived, as the Qin regime collapsed after a short lifespan.Footnote 39 As we shall see in Chapter 4, the Han government, or, for that matter, all the subsequent dynasties, had to confront a very difficult task of producing a sound currency policy.

Confucian Ideals

The key players of this age of reform – if we can use this term – were an emerging social group, the shi 士, literally “knight,” who originally belonged to the ruling nobility class. During the incessant political turmoil of the Spring and Autumn period when many noble families were brought down, their members became displaced and sought employment among those still powerful enough to stay in the game. With their knowledge of the affairs of the state, they gradually became, in a sense, advisors to the power holders, i.e., rulers, princes, or nobles of different ranks. They became people with knowledge, “intellectuals” who participated at every level of the government. Confucius, or Kongzi 孔子 (c. 551–476 BCE), was one such example.Footnote 40

Although credited with the founding of “Confucianism” or “Ru-ism,” Confucius himself was never aware of this term and was known to his contemporaries as a person with enthusiasm about propagating a set of moral principles derived from the Zhou dynasty ritual system. Confucius himself claimed that he only represented this system of ritual that the Duke of Zhou established without creating anything new, although he did in fact transform the meaning of the ritual system from outward court ceremonies to inward moral principles by teaching his followers through discussions and personal example.

According to the Confucian view, in order for a society to function harmoniously, all sorts of interpersonal relationships should be respectable and amicable. As later developed by Mencius (Mengzi 孟子, c. 372–289), Confucius’s spiritual disciple, people should follow a fivefold hierarchical order that defines all possible interpersonal relationships: “filiality between father and son, duty between ruler and subject, distinction between husband and wife, precedence of the old over young, and trust between friends.”Footnote 41 Except between friends, all the other four relationships are clearly hierarchical, that is, the former dominates the latter. This hierarchical order was explained as not being an outside requirement forced upon people, but rather an inner appreciation that grew out of mutual respect and appreciation. What was the nature of these relationships? From the perspective of emotion and empathy, the interpersonal relationship could be summarized in the concepts of benevolence (ren 仁) and forgiveness (shu 恕); from a rational perspective, the interpersonal relationship could be summarized in the concepts of loyalty (zhong 忠) and justice (yi 義). How these concepts were to be implemented in the five relationships without creating contradictions and impediments occupied a central position in the Confucian discourse. For example, Confucius said, “One who is benevolent loves people.” Yet this does not mean that one should love everyone with an equal amount of love, because different social relations would define different degrees of love. In comparison with the Christian concept of love, which, ideally, is an equal and undifferentiated love for all humankind, the Confucian love has to be considered in a hierarchical order based on the Five Relations. One could treat one’s enemy only with straightforwardness, but not love. In the end, when and if these virtues could be completely immersed and embodied in the Five Relations, society would have become an ideal world.

Since, like Socrates, Confucius, as well as his spiritual disciple Mencius, never put down his thoughts in writing, it is important that one should try to understand the major points of their ideas, and not insist on discovering a systematic philosophical treatise on moral philosophy. The Warring States Confucian thinker Xunzi 荀子 (313–239 BCE) was different, for he did write down his thoughts in a more systematic way. Xunzi discussed in his essays, for example, the origins of ritual and music, and human nature. He believed that human nature was evil by birth, and that only through education could one bend or guide this nature and force it to become good or to desire goodness. This theory is fundamentally opposite to that which Mencius propagated, that human nature was basically good, and there was an inner source of goodness that could be cultivated and expressed to become a positive force to benefit society. Both Xunzi and Mencius argued with a certain degree of persuasion, yet it is also understandable that their theories could generate debates, without producing firm answers, as the problem of human nature remains unsolved to this day.

In general, the Confucian thinkers were interested in developing a moral and political philosophy that could be of practical benefit to society at large, for this was the aim of their humanistic concern. This propensity of interest gravitated into a system of thought that combined personal and social ethics with a political philosophy based on the hierarchy of the Five Relations, which evolved into the fundamental ideology of government that underwent its most important period of growth during the Han dynasty.

The Dao and Its Proponents

In opposition to, or as a kind of critical reflection of, Confucian ideas was the strain of thought later coined as “Daoist,” with its leading characters Laozi 老子 and Zhuangzi 莊子. Leaving aside the complex issue of who is earlier than the other,Footnote 42 we can characterize the central idea of Daoism as a kind of naturalism. In contrast to the Confucian idea of active social responsibility and belief in the efficacies of moral teachings in achieving an ideal world, and also because they saw the weakness of human nature in its tendency to abuse power and wealth once in hand – along the line of thinking that “power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely” – the Daoist renounced the pursuit of political power and abandoned the cunning maneuvering in the insinuating intrigues of political struggles and opted for a life in tune with nature – simple, quiet, and spiritual, without the pursuit of material gains that went against nature and ultimately caused only anxiety, fear, doubt, and pain in one’s mind.

Being a kind of critical thought that was developed in response to the contemporary intellectual environment, which could be described as intellectual warring states that reflecting the political situation of the day, we need to see the Daoist idea of naturalism not only as a way of expressing disagreement with the Confucian ideal of social ethics, but also as an expression of disillusion with the contemporary political scene, in that the naked display of power crushed the livelihood of many ordinary people, mainly because the rulers had an incessant ambition to expand their power. Thus there was an underlying criticism in Laozi of the way politics were run by those with grandiose ideas, who taught the rulers how to rule, how to educate and mold the people into having a mindset of servitude in order to benefit the power holders. This was perhaps the true meaning behind the remark of Laozi: “Abandoning sainthood, forsaking wisdom, people will then return to the state of benevolence and filiality.” That is to say, the Confucian emphasis on following the examples of saints and moral teachings would only produce the opposite effect. Thus, “the better known the laws and edicts, the more thieves and robbers there are.”Footnote 43 One could therefore observe in Daoist thinking some elements that do not totally abandon this world or are alienated from contemporary society, but, on the contrary, offer a sense of compassion for the lives of the common people and provide a different route to alleviate some of the problems they suffered. This is why during the early Han dynasty Daoist rhetoric was adopted by the rulers, although only briefly, as a means of healing the war-torn society. This Daoist rhetoric, now assuming the name of Huang-lao, i.e., Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) and Laozi, was actually a blend of Daoist thought of Laozi and Zhuangzi and the Legalist attitude of the late Warring States period, most famously represented by people such as Shang Yang 商鞅 and Han Fei 韓非, about whom we shall have more to say in Chapter 3. Thus, ironically, the Lao-Zhuang Daoism of the pre-Qin era that originally despised secular power turned out to become Huang-lao Daoism of the early Han that served the secular regime.

A brief mention of the philosophy of Mozi should also be made here. A unique visionary with a radical idea of achieving peace in the world by promulgating the principle of universal love, Mozi, or the philosophy that this name represented, was nevertheless the product of his time, the late Warring States period. He accepted most of the Confucian ethics, but criticized the Confucians as prone to excessive ritual paraphernalia and of not being thrifty and prudent enough. His idea of “anti-aggression,” also a product of the Warring States period, was related to his “universal love,” because love brings peace, and when aggression is curtailed, peace could also be achieved. He also accepted the conventional religious ideas that revered Heaven, gods, and ghosts, and considered these useful to teach the people proper behavior. Mozi’s philosophy was prevalent for a time during the late Warring States period, but did not continue in the ensuing chaotic period of the Qin Han transition. Although one cannot pinpoint the reason, it could have to do with the very utilitarian attitude toward “love” and “peace.” Mozi’s reasoning was focused on the “benefits” one could have to promote “love” and “peace,” which might not have a deeper connection with one’s compassion and therefore lacking a lasting commitment.

By the end of the Warring States period, however, a more or less integrated cultural entity was beginning to emerge from the shadows of war. There were signs that show that people who lived in different parts of the land, whether in Gansu to the far west, Hubei to the south, or Shandong to the east, were adopting similar lifestyles by using the same divination system, observing similar funerary customs, obeying similar laws, and accepting a common dynastic ideology.

This situation indicates that the cultural landscape of China was undergoing a process of assimilation through times of war and peace. To be sure, the cultural differences among various areas, notably the Qin, based in the Wei River basin; the Jin, based in Shanxi; the Qi, based in Shandong; and the Chu, whose territory covered present-day Hubei and Hunan, were still noticeable even in the time of Sima Qian. They nonetheless were kneaded – voluntarily or not – into the same cultural outlook defined largely by the Zhou ritual system and ideology. More effort and time were needed for the states of Wu and Yue, which occupied the present-day lower Yangzi basin, and the Shu, in present-day Sichuan, to be integrated into the larger cultural sphere of the Hua/Xia people.

The complexity of the situation can also be shown by the use of different writing systems, such as the Qin, the Chu, the Shu, and the Central Plain Shang-Zhou system, not to mention the different spoken languages each area used. When the Qin finally unified the entire land, a single writing system was enforced to facilitate communication. Yet there was never an attempt to unify the spoken language until the twentieth century. The adoption of a unified writing script eventually led to the cultural unification of the country, the effect of which can be perceived throughout the following chapters (Fig. 5).

5. Han dynasty wooden slip roll.

This chapter thus sets the stage for the main acts in the subsequent chapters. For without this basic background such as the land, the historical development of the political regimes, the material condition of living, as well as the fundamental intellectual and religious propensity, many of the subsequent developments in the sphere of daily life, to which we shall pay special attention, would be less easy to imagine. Yet eager as we are to look at history from the bottom up, it would be better to have some idea of the superstructure of the society that we plan to explore. Such a structure, consisting of government organization and legal system, not only set a limit on the imagination and creativity of the elite, but also placed a restraint on the lives of ordinary citizens.