These lines from Vladimir Maiakovskii’s 1924 epic poem, Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, marked the creation of one of the Bolshevik Revolution’s central tropes – the kitchen maid that would rule the state. In the poem, the kitchen maid stood for the most exploited and disenfranchised laborers of tsarist Russia who would replace the former elites in running the state once the Bolsheviks had transformed them into conscious workers. Maiakovskii’s kitchen maid was a reference to one of Vladimir Lenin’s most important texts, the article “Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power?” written several weeks before the party’s seizure of power in October of 1917. Demanding inclusion of conscious workers and soldiers in the government after the autocracy had been overthrown in the February Revolution, Lenin wrote: “We are not utopians. We know that an unskilled laborer or a cook cannot immediately get on with the job of state administration.” Lenin then demanded that “a beginning be made at once in training all the working people, all the poor, for this work.”Footnote 2 In Maiakovskii’s poem, however, Lenin’s acknowledgment that cooks were not yet ready to participate in running the state became transformed into the declaration that they had the right and obligation to do so.

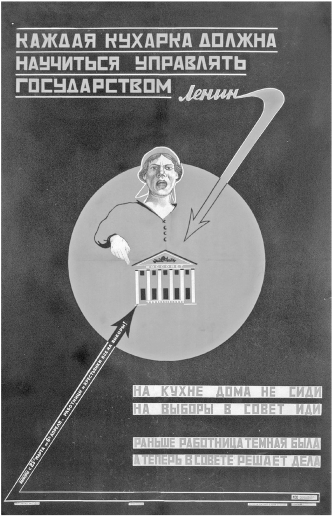

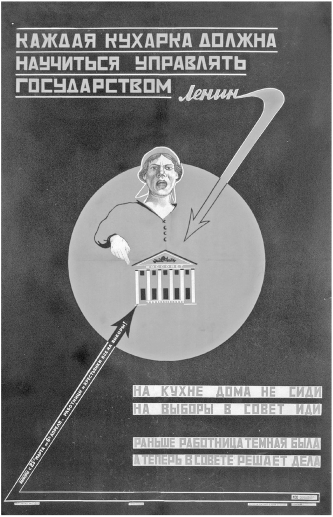

Lenin’s alleged words about the kitchen maid who would rule the state became one of the most recognizable symbols of Bolshevik egalitarianism (Figure I.1). Yet the lives of actual Soviet kitchen maids remained in their shadow. For Lenin, “they were not much more than a metaphor,” Angela Rustemeyer writes in the introduction to her study of domestic service in late imperial Russia.Footnote 3 This book challenges this statement in two ways. First, it argues that from the early days of Soviet power Bolsheviks grappled with the question of domestic service. Historians of the Soviet Union are well aware of the existence of paid domestic labor in the Soviet state. Nannies, cooks, and maids regularly appear in the pages of history books and articles. All of these works, however, share one underlying premise: Domestic service was something illicit, something that remained behind the closed doors of upper-class apartments.Footnote 4 The Bolsheviks were hostile “in principle toward personal services” and therefore the majority of families could not use paid domestic labor.Footnote 5 Domestic workers were barely mentioned in official publications and when they were, only in a negative context.Footnote 6 As we will see, however, paid domestic service was not something little discussed; rather, domestic labor was an object of public debate from the founding of the Soviet state into the 1950s. Moreover, the Soviet Union was the first state to introduce comprehensive pro-servant labor legislation, initiating history’s first government-led effort to recognize domestics as workers. By the mid-1930s, the Bolsheviks officially embraced paid domestic labor as an integral part of the socialist economy.

Figure I.1 “‘Every kitchen maid should learn to rule the state.’ Lenin”. Ilya P. Makarychev, 1925.

Second, this book demonstrates that the power of Lenin’s kitchen maid, rather than being “not much more than a metaphor,” is an entry point into Soviet conceptualizations of class and gender. The years following the publication of Maiakovskii’s Vladimir Il’ich Lenin saw an explosion of references to “Lenin’s kitchen maid.” They occupied a particularly prominent place in the campaign to mobilize and transform women. The power of the kitchen maid metaphor appealed doubly as a revolutionary symbol, in terms of both class and gender. Lenin’s kitchen maid was to represent the power of the new regime to transform “those who had nothing” into “those who have everything,” as the female domestic servant was the most backward, the most exploited victim of the tsarist oppression.Footnote 7

How was this persistence of paid domestic labor in the Soviet Union reconciled with Bolshevism’s central promise of revolutionary emancipation for all workers? This book explores why Bolsheviks embraced paid domestic labor as part of the socialist economy and how their approach to regulating domestic service affected the lives of domestic workers and their employers. The history of paid domestic labor in the Soviet Union serves not only as a window onto issues of class and gender inequality under socialism, but also as a new vantage point to examine the power and limitations of state initiatives to improve the lives of household workers in the modern world.Footnote 8

The Domestic Service Dilemma and the Gendered Hierarchy of Labor

When the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917, domestic service had long been associated with exploitation and inequality. It seems intuitive that paid domestic labor would have no place in the Soviet state. Even if domestic service persisted as a practice, it would exist in the gray area of informal relations. Yet, as this book will show, paid domestic labor not only remained legal throughout Soviet history, but was eventually embraced as part of the socialist economy. To understand this paradoxical legitimization of domestic service in the first socialist state, one needs to consider the meanings of class and gender as applied to paid domestic labor in the Soviet context. The contradictory interpretations of these categories formed the key tensions of the Soviet discourse on domestic service and are the focus of this book.

The Bolsheviks, following Marx, relied on one’s relationship to the means of production to define one’s class. Since domestic servants did not produce commodities, their employment was meaningless for class analysis.Footnote 9 Thus, employment of domestic servants did not mean exploitation in the Marxist sense. Moreover, even though Marxism was an egalitarian ideology, the Bolsheviks did not promise complete equality right away. Equality would only be possible once communism was achieved: There would be no exploitative classes and technology would create abundance. In the transitional period, a certain degree of inequality was inevitable because at this point the main goal of the revolutionary society was to create a sufficient material base for the transition, first to socialism, and then to communism. Different toilers had different skills and talents. The state needed to organize its labor force in the most rational manner to produce material goods in the most efficient way. This is why the state began to differentiate its citizens based on the value of their labor for the socialist project, thus creating a hierarchy of labor.Footnote 10 The privileges bestowed upon the most valuable laborers were not interpreted as class privileges but as proof that the Soviet state rewards labor.Footnote 11 I argue that the right to hire another person to work in one’s household was one such privilege.

My conceptualization of the ability to hire domestic workers as a privilege does not imply the corruption of Bolshevik principles, as famously argued by Stalin’s arch enemy, Leon Trotsky. In The Revolution Betrayed (1936), Trotsky used existence of domestic service as evidence of the embourgeoisement of Stalin’s elites and his failure to liberate women.Footnote 12 Trotsky’s accusations were echoed by the “Great Retreat” and “Big Deal” arguments by scholars, who conceptualized Stalin’s rule as a pulling back from revolutionary values that included rehabilitation of bourgeois lifestyle in exchange for loyalty of the new elites.Footnote 13 In this view, employment of domestic servants was part of the retreat.Footnote 14 I also disagree with historians who argue that the Bolsheviks betrayed their revolutionary values immediately after winning the Civil War by hiring domestic servants as symbols of power.Footnote 15 Finally, I do not contend that the ubiquity of paid domestic labor in the homes of Soviet elite was a sign of persistence of traditional domesticity that ultimately undermined the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary ambition.Footnote 16 Instead, I maintain that the hierarchy of labor was an intrinsic part of the revolutionary project and grounded in the Bolsheviks’ understanding of Marxism. Resting on the hierarchy of labor as necessary for building a socialist society, paid domestic labor served the state’s modernizing goals in the realm of domestic life.Footnote 17 Most importantly, I demonstrate that this hierarchy of labor was fundamentally gendered.

Emancipation of women – meaning their equal participation in building socialism – was one of the cornerstones of the Marxist revolutionary vision. Emancipation was conditioned on women’s liberation from housework, which socialist thinkers viewed as laborious and unpleasant. In their writings, Marx and Engels suggested that domestic labor under socialism would be removed from the household and transferred to public industry.Footnote 18 When the Bolsheviks came to power, the collectivization of housework outside of the home was a hallmark of their program of women’s emancipation. According to the Bolsheviks, creation of a public industry of communal services would solve two problems. Relieved of their duties in the home, women would have time to engage both in productive work and in politics. In other words, freedom from housework would allow women to become conscious political subjects. Their political development was of crucial importance because building socialism was possible only if the population purposefully engaged in it. The second benefit of transferring housework to public industry was efficiency. The Bolsheviks believed that professionals employed at public cafeterias, laundries, and crèches would be better than housewives at cooking, washing laundry, and raising children. Indeed, domestic labor within individual homes could never be organized as rationally as within a service industry.Footnote 19

While liberation of women was essential for the revolution and collectivization of housework was to serve many purposes, the Bolsheviks conceptualized the problem of housework as a woman’s problem. In his famous speech at the Fourth Moscow City Conference of Non-Party Working Women in 1919, Lenin explicitly presented socialization of housework as a policy aimed at women: “We are setting up model institutions, dining-rooms, and nurseries that will emancipate women from housework. And the work of organizing all these institutions will fall mainly to women.”Footnote 20 According to Soviet propaganda, women had the most to gain from reorganization of everyday life because new institutions would free them from housework.Footnote 21 Most importantly, even though the most ardent Bolshevik champion of women’s liberation, Aleksandra Kollontai, suggested that both men and women should be involved in collective housekeeping, and Vladimir Lenin chastised proletarian men for failing to ease their wives’ burden by “lending a hand in ‘women’s work,’” the Bolsheviks never proposed redistribution of labor within the home as a way to achieve women’s emancipation.Footnote 22 When Soviet propaganda encouraged men to do housework, they were conceptualized as “helping” women.Footnote 23 Even when Stalin’s death allowed for a public discussion of men’s insufficient involvement in housework and childrearing, it did not lead to the fundamental rethinking of gender roles or the redistribution of labor in the home as a path to women’s emancipation comparable to the Cuban Family Code of 1974 that codified equal division of labor between spouses.Footnote 24 Thus, from the point of view of the country’s leadership, building public facilities would benefit women first and foremost, while increasing production was crucial for the larger goal of building socialism. Therefore, the Bolsheviks prioritized production over reproduction, investing most of the country’s limited resources in factories rather than daycare centers or laundry facilities.Footnote 25 In the meantime, it was women who were to pick up the load and make sure that their husbands and children were fed, their clothes washed, and homes cleaned. The Bolsheviks’ desire to emancipate women ran up against a gendered vision of society in which housework was women’s work.

If complete socialization of housework was the plan for a rather distant future, what was to be the place of domestic labor performed by individual women in Soviet society? Lenin famously called household labor “the most unproductive, the most barbarous, and the most arduous work a woman can do.”Footnote 26 Kollontai unequivocally stated that household chores “are of no value to the state and the national economy, for they do not create any new values or make any contribution to the prosperity of the country.”Footnote 27 These statements, as important as they were, are only part of the story. The history of domestic service in the Soviet Union reveals that party attitudes toward domestic labor were not uniform and evolved over time. While in the early revolutionary years the Bolsheviks were dismissive of domestic labor, they eventually recognized its value, if not in the Marxist sense, then in the sense that it was important for the achievement of their revolutionary goals.Footnote 28 By the mid-1930s, official Soviet discourse began to celebrate the work that wives and mothers did in the home: A well-maintained home ensured high productivity at work and proper parenting was a contribution to the country’s future. Even though it was less valuable than work at factories and in offices, housework was labor that contributed to the collective good. In that regard, the Soviet Union differed from contemporary capitalist societies that did not see housework as labor. The Soviet approach to housework was also distinct from that of Maoist China, where the official discourse did not publicly recognize the value of work of women in the home.Footnote 29

The Soviet state recognized the significance of domestic labor for the socialist economy. However, due to the successful mobilization of women in the urban public sphere, many of them had little time to perform this important work in the home: In the cities, the more women became gainfully employed and politically active, in the context of a deficit of public services, the more acute the problem of housework became. The solution was to shift the burden of housework from skilled urban women to unskilled female peasant migrants, and thus to free urban women’s skilled labor for production. Thus, a history of domestic service complicates a familiar story of the Soviet gender order, in which the state failed to create the comprehensive network of reliable services such as public cafeterias, laundromats, or daycare centers Bolshevik revolutionaries imagined and instead saddled Soviet women with “double burden” of work outside and inside the home. In fact, many educated urban women shifted much of their domestic burden onto the shoulders of their maids and nannies because the regime recognized privately employed household workers as a legitimate alternative to public services.

I argue that this recognition of servants as workers, who were performing tasks of social value, not only affected the lives of women in privileged households but also fundamentally changed the social position of their employees. Labor historians have done a lot to understand who or what constituted the Soviet working class. Much of this history, however, has dealt with the industrial proletariat, with only few works dedicated to other kinds of labor.Footnote 30 Such focus inevitably leads to privileging the stories of groups with long history of organized militancy and strong class identity.Footnote 31 Domestic workers, however, had been historically excluded from the working class and had a limited history of participation in the workers’ movement. Only under the Soviet power were servants admitted into the proletarian family with all the rights and obligations that came with such status. A history of domestic workers opens a unique opportunity to investigate what it meant to be ascribed to the working class, to use Sheila Fitzpatrick’s term.Footnote 32 The book shows that the Bolsheviks had an inclusive understanding of the proletariat and that they were serious in their attempt to transform into proletarian workers even servants who were marginal to industrial production.

The key tools of this transformation were professional unions that provided domestic workers with legal and educational services and enforced pro-servant labor laws. Most historians are in agreement that Russian labor unions gradually lost their political power after 1917: If in the 1920s they were still a formidable force the party had to reckon with, by the end of the decade unions had become bureaucratic structures meant to regulate the labor force on behalf of the state.Footnote 33 This book offers a history of workers whose professional organization was mostly formed after the revolution. It demonstrates that these union structures were crucial in protecting the rights of their members. Moreover, union oversight was a still significant factor in labor relations after 1930. It has been argued that even though state unions could intervene on behalf of individual workers, they could not protect workers’ collective interests against management.Footnote 34 Without disputing the party’s control over state unions under Stalin, this book emphasizes the significance of such individual interventions, which were particularly important for domestics. At a time when collective bargaining was completely inaccessible to their peers in other countries (and is still rarely available today), such interventions were at the heart of the transformation from servants into workers and had a real impact on domestics’ lives. As a result, domestic workers’ labor rights in the Soviet Union were protected better than anywhere in the world.

The acceptance of domestics as workers and the recognition of the social value of housework informed two competing goals of Soviet policies on domestic service: first, the protection of domestic workers’ rights; and second, making their labor more accessible to urban households. The former was at the heart of early Soviet policies and related debates. The latter became central during Stalin’s industrialization. Only after Stalin’s death did the issue of domestic worker’s rights resurface in discussions of paid domestic labor. While different approaches to domestic service were dominant in different periods of Soviet history, a consensus never emerged on the question of paid domestic labor because the fundamental tensions were never resolved. Even though paid domestic labor did not constitute exploitation in the Marxist sense, for many Soviet citizens it remained a symbol of inequality incompatible with the emancipatory promise. While newspapers praised domestic workers for freeing up the labor of their employers and thus contributing to building socialism, many domestics saw their work in the nonproductive domestic sphere as degrading. These tensions drove the debates about paid domestic labor until the 1960s, when the number of domestic workers declined significantly, and domestic service no longer attracted attention.

For forty years the Bolsheviks had to deal with what sociologist Shireen Ally called the “domestic service dilemma.” The term seeks to capture the difficult choices feminists in the capitalist world had to make when they confronted “the possibility of paid domestic work as a way of resolving their gendered responsibility for domestic labor.”Footnote 35 For the Bolsheviks, it was the strong association between domestic service and class inequality, rather than its gendered nature, that made the practice problematic. Whenever Soviet citizens expressed dissatisfaction with the persistence of paid domestic labor, they utilized the language of class, in the post-Stalin period substituted by the language of merit and privilege, to point out that it was those who had less who were working for those who had more. Yet, among hundreds of documents, publications in the press, and works of fiction and film relating to the issue of paid domestic labor, one searches in vain for voices that question the fact that it was women who were hired to do the housework. As this book will show, the debates about domestic service in fact reinforced the gendered division of labor.

This persistence of the normative understanding of domestic service as feminine was consistent with the paradoxical nature of the Bolsheviks’ regendering of the workforce as documented by labor historians. With the growth of Soviet industry women gained access to many jobs previously coded as masculine.Footnote 36 Women’s contributions in these new positions as well as in traditionally feminized sectors of the economy were celebrated, including domestic service.Footnote 37 At the same time, the workforce remained segregated by gender, as women predominantly clustered in jobs that had been traditionally considered, or newly designated as, female.Footnote 38 The celebration of women’s work also heavily relied on essentialized notions of women’s qualities, thus reinforcing gender stereotypes.Footnote 39 Most importantly, women’s labor, while praised, was never valued as highly as work that was gendered masculine. The recognition of servants as workers was limited by the gendering of service work – particularly in the home – as female, and therefore not quite on par with the “real work” in production. Domestics, while embracing their status as workers, understood their role as inferior to those of other proletarians and actively sought to leave service. As Diane Koenker writes in her study of waitressing in late Soviet society, “[t]he gendering of Soviet service occupations consolidated the equation of service work as female and second-rate.”Footnote 40 In this regard, the Soviet case is strikingly similar to other modern societies which devalue paid domestic work because it is associated with unpaid housework, performed largely by women.Footnote 41

The gendering of domestic service as female also shaped laws and educational efforts that relied on the notion of servants’ particular backwardness. The definition of domestic servants as “vulnerable” implied a subject status with compromised capacity.Footnote 42 The state sought to empower domestic servants, but the backwardness framework set limits to active participation in their own refashioning. This tension between a sincere desire to liberate and the disempowering framework of vulnerability and backwardness is familiar to historians of gender in the Soviet Union. While serious about equality between men and women, the Bolshevik leadership was highly suspicious of women, especially peasant women, fearing that they could sabotage the new order because of their “backwardness.”Footnote 43 Therefore, Soviet activists conceived of the emancipation of women not only in terms of employment opportunities and lessening the burden of household chores, but as a profound identity change, a transformation of the baba into a comrade – a conscious Soviet citizen.Footnote 44 The New Soviet Person was not, however, gender-neutral. Soviet educational activities and other forms of propaganda instilled in Soviet women particular ideas about what it meant to be a woman in the Soviet state. The history of domestic service shows how the conflict between the emancipatory thrust of the revolution and the traditional view of gender roles affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of women in the Soviet Union. These contradictions, I argue, could be both liberating and oppressive.Footnote 45 As the book will demonstrate, the Soviet state created opportunities for domestic workers unheard of in other states, while simultaneously thwarting their agency.

The Bolsheviks’ approach to domestic service reveals the gendered hierarchy of labor that lay at the heart of Soviet society. This is not to say that this approach was predetermined by Marxism. In fact, the histories of other communist governments show that Marxism could inspire a spectrum of decisions regarding domestic service: from total legitimization as part of a socialist economy, to tacit toleration as an elite practice, to outright prohibition. In the first decades of the People’s Republic of China, employment of domestics was limited to urban elites who hired servants with permission of the party.Footnote 46 The practice was criticized as bourgeois during the Cultural Revolution, only to be rehabilitated in the early 1980s as a “practical solution to the problems that so many urban couples face in coping with domestic work and child care.”Footnote 47 It was only then that household employees were officially recognized as “workers.”Footnote 48 Domestic service in the Republic of Cuba had a similarly nonlinear trajectory. While in the first years of the republic some voices in the new government called for labor rights for domestic servants, in 1961 private employment of domestics was deemed incompatible with the goals of the revolution and former servants were retrained in highly publicized schools.Footnote 49 In the following decades, “women who help” would exist on the “gray” market until 1993 when the government passed a law expanding private businesses that listed domestic service as one of the many newly legal jobs.Footnote 50 Thus, as the following chapters will show, the Soviet approach to paid domestic labor was not predetermined but stemmed from the Bolsheviks’ reading of Marxism, the Russian cultural context, and the economic, social, and political circumstances of the first four decades of Soviet rule.

Thus, Domestic Service in the Soviet Union contributes to the conversation about persistence of paid domestic labor in the modern world and the difficulty democratic and feminist movements have had resolving the domestic service dilemma. The book expands the scope of this debate by examining the persistence of paid domestic labor under socialism. It demonstrates the abilities and limitations of pro-worker legislation and state-supported unions to improve the lives of household workers in a society extremely sensitive to the class inequalities at the heart of domestic service but oblivious to their gendered dimension.

Voices and Sources

“Immured in their basements and attic bedrooms, shut away from private gaze and public conscience, the domestic servants remained mute and forgotten until, in the end, only their growing scarcity aroused interest in ‘the servant problem,’” wrote the historian John Burnett about domestic servants in Britain at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 51 Burnett’s vision of domestic servants as “mute and forgotten” inspired historians to conduct research that would give domestics a voice, and make them visible in the broader historical narratives. Burnett’s statement also pointed to the difficulty historians would encounter in trying to uncover those voices: The archives and the printed discourses would be dominated by masters rather than servants.

As the following chapters will show, Soviet domestic workers were neither “forgotten” nor “mute.” Rather than being an illicit practice, domestic service was an object of lively debate during the first four decades of Soviet history. Regulation of paid domestic labor was widely discussed in the Soviet press and state institutions. Maids and nannies were ubiquitous in Soviet literature and film. Documents produced by Soviet institutions and articles in Soviet newspapers were full of testimonies of domestic workers as well as activists who worked with them. These materials are the primary sources of this study. They are not merely documentary repositories but congealed forms of the revolutionary regime’s transformative agenda. The Soviet state actively sought out domestic workers in order to mold them into exemplary Soviet citizens and used the image of the domestic worker as a powerful symbol of both female oppression and emancipation. The variety of texts and images created in the process were an essential part of revolutionary politics.

Labor unions were the institutions central to the history of domestic service in the Soviet Union. Once the Bolsheviks took power, they invested great effort in suppressing and co-opting the Russian workers’ movement. There were several stages of this subjugation of the labor unions: the creation of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (1918); the party discussion of the role of labor unions in the Soviet state, which reaffirmed their position as the party’s “transmission belts” (1921); the “turn to production campaign,” which redefined labor unions as tools for labor mobilization (1929); a series of union reorganizations and removal of the old leadership (1930, 1934); and the disbanding of the People’s Commissariat of Labor and making the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions its successor, thus finalizing unions’ transformation into institutions of labor regulation and welfare provision (1933). Thus, Soviet labor unions were state institutions that adhered to the party line. However, this does not mean that they offered no space for agency. Throughout the Soviet period discussions within unions had an impact on state policies. Even when decisions were made in the Kremlin, room for interpretation and contestation remained at different levels: in the unions’ central committees, regional (republican) union organizations, and local committees.Footnote 52

Four consecutive unions were to recruit domestic workers so that they were incorporated in the project of building socialism in the first four decades of the Soviet state: the Professional Union of People’s Food Service and Dormitory Workers (Narpit) (1918–1930), the Professional Union of Workers of City Enterprises and Domestic Workers (PUWCEDW) (1930–1934), the Professional Union of Workers of Housing Services (PUWHS) (1934–1947), and the Professional Union of Workers of Communal Services (PUWCS) (1948–1957). Documentation from these unions in state and local archives contains voices of multiple actors: the union leadership, representatives of other institutions, local union administrators, rank-and-file activists, and domestic workers. These voices were often amplified in brochures, booklets, and journals published by the union press. While the unions served as “transmission belts” for the party agenda, they remained important sites where this agenda was debated, appropriated, and contested.

Just as activists in state labor unions did not simply enforce policies promulgated by party leaders, Soviet journalists, writers, and film directors did not simply reproduce official discourse on domestic service. Rather, they creatively engaging with this discourse, transforming it in the process.Footnote 53 Their works show us how Bolshevik visions were appropriated and reworked by institutions and individuals. They also demonstrate that, even at the height of Stalinist terror, competing ideas about the place of domestic service under socialism existed in the Soviet public sphere, testifying to the unresolved tensions in the understanding of paid domestic labor.

Journalists, writers, and filmmakers as representatives of Soviet creative intelligentsia were undoubtably from the milieu that hired household workers (if not necessarily employers of domestic workers themselves). Yet hardly any of them spoke from the position of employers the way their imperial predecessors or non-Soviet counterparts did. In fact, the voices of employers are absent from the public discussions. Except for a brief moment in the late 1930s, no Soviet newspapers published “letters from employers of domestic workers.” To access the voices of employers, this book relies on retrospective sources – memoirs and interviews.Footnote 54 While such sources have their limits (like other sources, too), they provide invaluable insights into an aspect of domestic service that is absent from archives and the pages of the Soviet press – the relationships within the households. These sources are key to understanding the extent to which Soviet discourse transformed the lives of domestic workers and the families that employed them.

Domestic workers’ voices are of crucial importance for this project. So are the voices of their employers, union activists, party functionaries, and the artistic intelligentsia. The presence of so many actors in the debate about domestic service testifies to its importance to Soviet policy.

The Scope of This Book

Soviet censuses taken in 1926, 1937, and 1939 consistently recorded roughly half a million domestic workers.Footnote 55 Almost all of them were single women.Footnote 56 The already small number of men in domestic service declined rapidly between 1926 and 1939, from 3,762 to 582.Footnote 57 Paid domestic labor was also becoming an increasingly urban phenomenon, with 84 percent of domestics being employed in towns and cities in 1939 compared to 71 percent in 1926.Footnote 58 The biggest cities had the most demand for paid domestic labor, with Moscow accounting for almost 10 percent of all domestics in the country (42,255), followed by Leningrad (25,318) and Kharkov (10,463) in 1926.Footnote 59 The majority of domestics working in these urban areas were peasant migrants.Footnote 60 With no place of their own in the city, they primarily lived with their employers: One study from 1926 stated that over 90 percent of all domestics in Moscow were live-in.Footnote 61 Soviet domestic workers rarely specialized in particular kinds of service. According to the 1926 census, over 75 percent of domestics were employed as “maids of all works,” performing a range of duties around the house, including cooking, cleaning, and looking after children. The rest were nannies, who made up almost 20 percent urban domestics, and cooks, who accounted for slightly over 5 percent.Footnote 62 Domestics were also mostly young, though the percentage of domestics under the age of thirty declined from 78 percent in 1926 to 62 percent in 1939.Footnote 63

Finally, most domestic workers in the Soviet Union were Russian. About two-thirds of Soviet domestics lived in Russia.Footnote 64 Only in Ukraine and Belarus did “titular nationalities,” Ukrainians and Belarussians, account for majority of urban domestics (68 percent and 66 percent, respectively).Footnote 65 In all non-Russian republics, Russian women were overrepresented among domestics. For example, in the Kharkov district, only 32 percent of all women were Russian, whereas Russians accounted for 44 percent of domestic workers.Footnote 66 In the Kiev district, 21 percent of domestics were Russian, while Russians only made up 9 percent of the general female population.Footnote 67 Russian women appear to have taken on jobs in domestic service declined by Jewish women, who made up a significant percentage of the population in both cities. The case of Minsk is even clearer in this regard: Only six percent of domestics in the city were Jewish, while Jews accounted for about 40 percent of the population.Footnote 68 Domestic service as an occupation for peasant migrants had little appeal for Jewish women, who were mostly born in urban areas. Muslim women were even less likely to be employed in domestic service. Out of 3,502 domestics working in Uzbekistan, only eighty-six were Uzbek, twelve were Tajik, and twelve belonged to “other indigenous groups,” according to the 1926 census. The rest were recorded as “nonindigenous,” meaning mostly Russian.Footnote 69 Out of 6,320 female servants in Baku, 4,622 were Russian and only 278 were recorded as “Turkic.”Footnote 70 Few Muslim women worked in domestic service because Islam restricted women’s employment outside the home, limiting their ability to seek jobs in domestic service. Simultaneously, because Muslim women rarely worked outside the home, their families could rely on them for housework and had less need for paid domestic labor.

Thus, young Russian peasant migrant women employed in urban areas as full-time live-in maids of all works are the main protagonists of this book, with older, non-Russian, nonpeasant women, and those employed in rural areas making occasional appearances. This focus leaves out other kinds of arrangements between those who provided services and those who received them. Along with live-in cooks and nannies, people hired day laborers, cleaners, and laundresses and paid them by the hour. There was a certain number of women who looked after a neighbor’s child for extra cash. The 1926 census recorded 13,490 individuals working in domestic service in addition to their primary occupation.Footnote 71 There were girls and women working in other people’s homes in the countryside. Following an established tradition, peasant families sent their daughters (and sometimes sons), often as young as six or seven, to the homes of wealthier neighbors as childminders. They would come back to their families once they were old enough for agricultural labor.Footnote 72 According to the 1926 census, 57,443 girls and 672 boys under the age of fifteen worked in domestic service in the countryside, mostly as nannies, 49,712 and 577, respectively.Footnote 73 Before agriculture was collectivized in the 1930s, there were a significant number of female agricultural laborers (batrachki) who did some work around the house in addition to working in the field. Some families also chose to bring in poor relatives to help around the house. Another group of domestic workers were political prisoners, deportees, and later prisoners of war, who worked in the homes of Gulag employees. Many of them were men who served as orderlies for male Gulag administrators.Footnote 74 All of these forms of domestic service are beyond the scope of this book, as they were not discussed in general debates about paid domestic labor. The live-in female workers who cooked, cleaned, and looked after children in urban homes in exchange for wages, food, or shelter were the “typical” domestic workers (domrabotnitsy) of the 1920s–1950s. These were the domestic workers imagined by the state officials who drafted policies on paid domestic labor, and portrayed by the artistic intelligentsia.

This book traces the evolution of domestic service in the Soviet Union against the background of changing discourses on women, labor, and socialist living. It covers the period from the revolution of 1917 to the rapid decline of live-in domestic service in the 1960s. This chronological framework is not common for histories of socialism in Russia as it cuts through the conventional division into early Soviet, Stalinist, and late-Soviet periods. Yet it makes sense if we follow the demographic history of Soviet urbanization, as constant migration of women from the countryside served as an endless pool of domestic workers until the flow began to dry in the 1960s. In order to analyze continuities and ruptures in the functioning of domestic service in the Soviet Union, the chapters are structured chronologically as well as thematically. This approach allows me to write the story of paid domestic labor as part of a larger historical narrative and to emphasize the connection between the changes in domestic service and socioeconomic and political shifts in the country as a whole.

The first four chapters constitute the first section of the book. It analyzes the efforts to transform servants into workers in the early days of the Soviet state, from the Bolsheviks’ ascendance to power in 1917 to the end of the New Economic Policy in 1928. The first decade of Soviet power was the time when the key notions of socialist living were articulated. These ideas in one form or another would define the Soviet experience for decades to come. Chapter 1 analyzes the shift in the understanding of domestic service from a problematic institution intrinsically connected to inequality and exploitation to an acceptable practice. It argues that the attitude toward paid domestic labor changed because Soviet authorities began to recognize the social value of domestic labor. Chapter 2 demonstrates how this shift affected some aspects of domestic workers’ rights but not others. While domestic workers’ labor rights were limited by a new law on domestic service to make their labor more accessible to employers, the state was reluctant to limit their access to their employers’ housing after termination of contract, because female homelessness was closely associated with prostitution. The new law put domestic workers in a disadvantaged position compared to other workers, which, together with continuing valorization of “productive” labor, made domestics seek employment opportunities outside domestic service. The low status of domestic service in the Soviet hierarchy of labor undermined efforts to draw domestic workers into activism through union mobilization, as argued in Chapter 3. Even though some domestics found union activism attractive as a means to reinvent themselves as class-conscious workers, the overall results of the campaign were underwhelming: The appeal of “productive” work inspired domestics to use their activism as a springboard for careers outside of domestic service rather than for organizing their peers. Domestics’ reluctance to engage with the union only confirmed the long-standing suspicion that domestic service fostered “lackey’s souls” rather than conscious proletarian selves. The union’s educational campaign discussed in Chapter 4 was meant to reshape domestics to fit them into the proletarian mold. The union’s disciplining approach, however, provided space for domestic workers to creatively engage with the official discourse and use it to claim a place in the revolutionary society or to take the state to task for failing them.

The Bolsheviks saw the 1920s as a transitional period of mixed economy that Lenin himself defined as “state capitalism.” With the introduction of the First Five-Year Plan at the end of the decade, the Bolsheviks began an accelerated transition to socialism proper. By the mid-1930s, according to the country’s leader Joseph Stalin, the foundations of socialism had been built. The construction of socialism and its meaning for domestic service is the focus of the second part of the book. As Chapter 5 demonstrates, the country’s “turn to production” in the late 1920s rendered “nonproductive” domestic labor irrelevant for socialism. During these ambitious years of forced industrialization, domestic service was proclaimed a thing of the past: Domestic workers were to be retrained and sent to the public sector. This notion, however, was soon revisited. With the official transition to socialism in the mid-1930s, domestic service was reimagined as an integral part of the socialist economy. Yet, as Chapter 6 reveals, the recognition of domestic workers as equal builders of socialism only solidified the gendered hierarchy of labor. As a result, many Soviet citizens continued to view domestic labor as degrading. The transition to socialism also meant that the relationships between domestic workers and their employers had to be reimagined. While official discourse encouraged domestics and employers to treat each other not just as parties in a labor contract but as family members, domestic service remained a site of intense economic, cultural, and emotional interactions. These negotiations are the focus of Chapter 7. The book concludes with the study of paid domestic labor in postwar society. While in the rest of Europe World War II brought about a rapid decline in residential domestic service, the Soviet Union saw solidification of class and gender privileges that laid at the heart of domestic service. As Chapter 8 demonstrates, after Stalin’s death, domestic service became a vehicle to discuss class inequality in Soviet society. Gender inequality, however, was never questioned. On the contrary, the debates around paid domestic labor only reinforced the notion that was fundamental to gender inequality in the Soviet Union: that housework was women’s work.