Book contents

- Cities of Strangers

- The Wiles Lectures

- Cities of Strangers

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Maps

- Chapter 1 Cities and Their Strangers

- Chapter 2 Strangers into Neighbours

- Chapter 3 Jews: Familiar Strangers

- Chapter 4 Women: Sometimes Strangers in Their Cities

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 March 2020

- Cities of Strangers

- The Wiles Lectures

- Cities of Strangers

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Maps

- Chapter 1 Cities and Their Strangers

- Chapter 2 Strangers into Neighbours

- Chapter 3 Jews: Familiar Strangers

- Chapter 4 Women: Sometimes Strangers in Their Cities

- Conclusion

- Notes

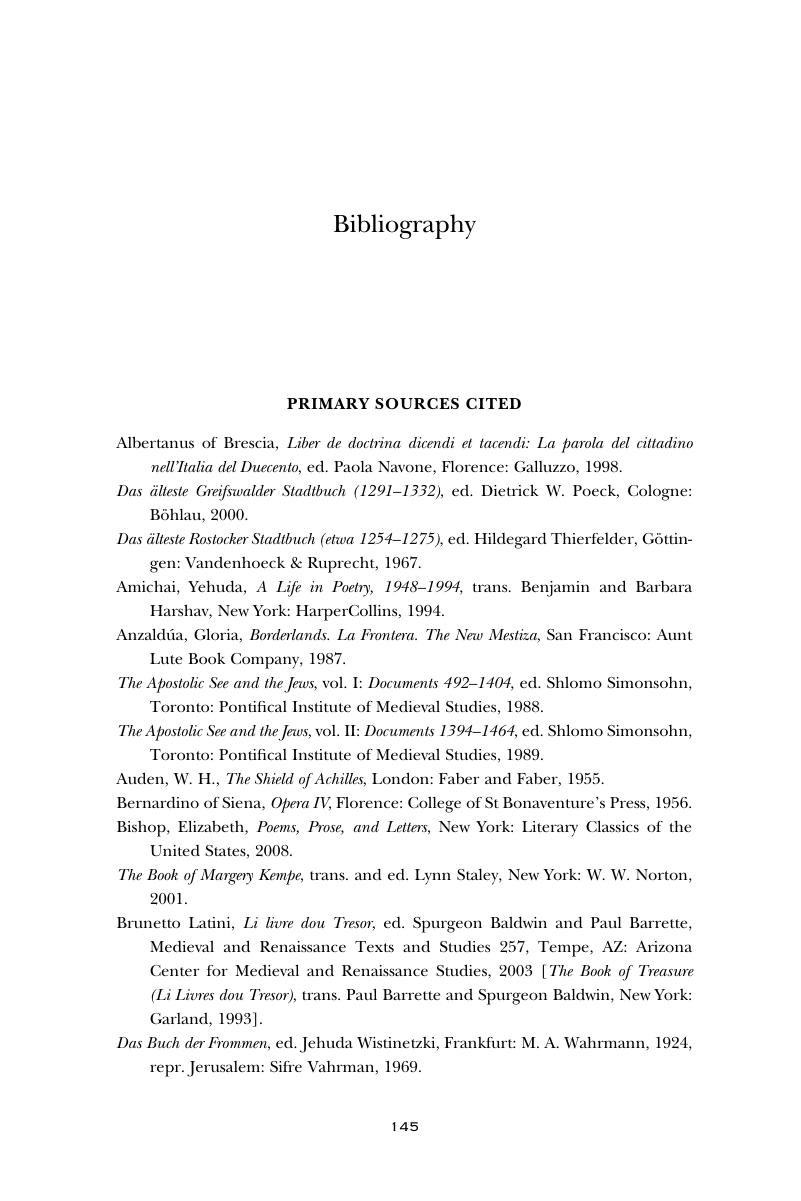

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Cities of StrangersMaking Lives in Medieval Europe, pp. 145 - 184Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020