Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- A Torn Narrative of Violence

- I Did Not Expect Such a Thing to Happen

- (Dis)connections: Elite and Popular ‘Common Sense’ on the Matter of ‘Foreigners’

- Xenophobia in Alexandra

- Behind Xenophobia in South Africa – Poverty or Inequality?

- Relative Deprivation, Social Instability and Cultures of Entitlement

- Violence, Condemnation, and the Meaning of Living in South Africa

- Crossing Borders

- Policing Xenophobia – Xenophobic Policing: A Clash of Legitimacy

- Housing Delivery, the Urban Crisis and Xenophobia

- Two Newspapers, Two Nations? The Media and the Xenophobic Violence

- Beyond Citizenship: Human Rights and Democracy

- We Are Not All Like That: Race, Class and Nation after Apartheid

- Brutal Inheritances: Echoes, Negrophobia and Masculinist Violence

- Constructing the ‘Other’: Learning from the Ivorian Example

- End Notes

- Author Biographies

Behind Xenophobia in South Africa – Poverty or Inequality?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- A Torn Narrative of Violence

- I Did Not Expect Such a Thing to Happen

- (Dis)connections: Elite and Popular ‘Common Sense’ on the Matter of ‘Foreigners’

- Xenophobia in Alexandra

- Behind Xenophobia in South Africa – Poverty or Inequality?

- Relative Deprivation, Social Instability and Cultures of Entitlement

- Violence, Condemnation, and the Meaning of Living in South Africa

- Crossing Borders

- Policing Xenophobia – Xenophobic Policing: A Clash of Legitimacy

- Housing Delivery, the Urban Crisis and Xenophobia

- Two Newspapers, Two Nations? The Media and the Xenophobic Violence

- Beyond Citizenship: Human Rights and Democracy

- We Are Not All Like That: Race, Class and Nation after Apartheid

- Brutal Inheritances: Echoes, Negrophobia and Masculinist Violence

- Constructing the ‘Other’: Learning from the Ivorian Example

- End Notes

- Author Biographies

Summary

Many commentators have identified one important set of factors underlying the violence in townships and squatter areas during May to be mounting difficulties faced by poor people. When asked by journalists why the violence had occurred, residents in these areas referred to issues including crime, lack of work, and lack of housing and basic services. Government – in the form of minister Essop Pahad – argued that the violence must be the work of a ‘third force’ since South Africa has done more than any other developing country for the poor. I would argue that to the extent the violence is linked to the economic circumstances of poor people, it is not the result of poverty per se, but rather of inequality. It is surely not simply that people are poor which leads them to attack other poor people, but instead the sense of unfairness engendered by inequality, of being discriminated against, which creates the resentments and hostility towards those perceived, rightly or wrongly, to be better off or to have received preferential treatment.

INEQUALITY IS DISTINCT FROM POVERTY

The main point of this chapter is that poverty and inequality are distinct issues: they are not the same thing and cannot be addressed by policy as if they are. There is no doubt of course that both poverty and inequality are intractable and deeply-rooted issues in South Africa. In 2005, 47 per cent of the population was in poverty using the widely-agreed poverty line of R322 per capita per month in 2000 prices. This proportion was below the 2000 level of 53 per cent, but was nonetheless inordinately high.

Inequality is perhaps even starker. In 2006, the Gini coefficient was officially calculated at 0.73, certainly amongst the two or three highest globally. More revealing perhaps was that the richest 10 per cent of the population received 51 per cent of total household income, while the poorest 10 per cent received a mere 0.2 per cent, the ratio of average income between the two groups thus amounting to a massive 255:1. The richest 20 per cent of the population received 68.8 per cent of the total income, compared with the poorest 20 per cent obtaining only 1.4 per cent, a ratio of 49:1.

- Type

- Chapter

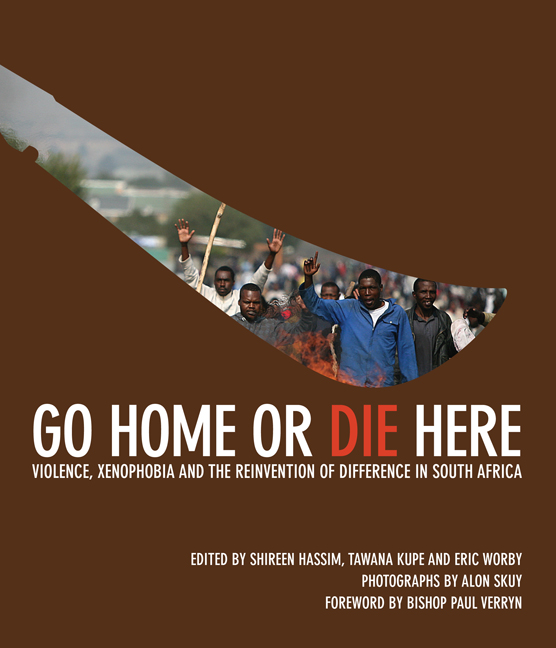

- Information

- Go Home or Die HereViolence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa, pp. 79 - 92Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2008