Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

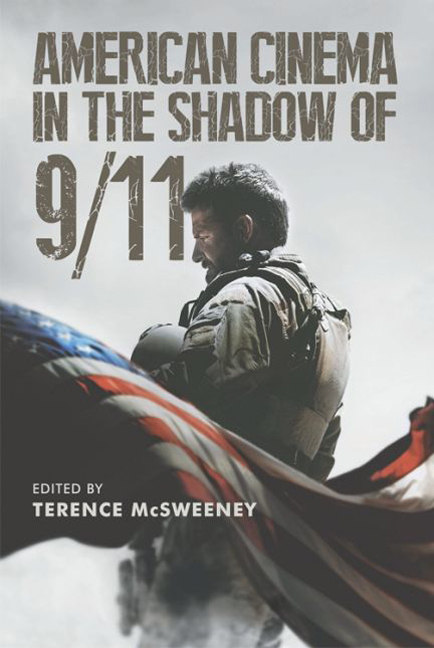

- Introduction: American Cinema in the Shadow of 9/11

- Part I Dramatisations of the ‘War on Terror’

- Part II Influences of the ‘War on Terror’

- 6 ‘Not Now That Strength’: Embodiment and Globalisation in Post-9/11 James Bond

- 7 Training the Body Politic: Networked Masculinity and the ‘War on Terror’ in Hollywood Film

- 8 ‘Gettin' Dirty’: Tarantino's Vengeful Justice, the Marked Viewer and Post-9/11 America

- 9 Stop the Clocks: Lincoln and Post-9/11 Cinema

- 10 Foreshadows of the Fall: Questioning 9/11's Impact on American Attitudes

- Part III Allegories of the ‘War on Terror’

- Selected Filmography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

8 - ‘Gettin' Dirty’: Tarantino's Vengeful Justice, the Marked Viewer and Post-9/11 America

from Part II - Influences of the ‘War on Terror’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 May 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction: American Cinema in the Shadow of 9/11

- Part I Dramatisations of the ‘War on Terror’

- Part II Influences of the ‘War on Terror’

- 6 ‘Not Now That Strength’: Embodiment and Globalisation in Post-9/11 James Bond

- 7 Training the Body Politic: Networked Masculinity and the ‘War on Terror’ in Hollywood Film

- 8 ‘Gettin' Dirty’: Tarantino's Vengeful Justice, the Marked Viewer and Post-9/11 America

- 9 Stop the Clocks: Lincoln and Post-9/11 Cinema

- 10 Foreshadows of the Fall: Questioning 9/11's Impact on American Attitudes

- Part III Allegories of the ‘War on Terror’

- Selected Filmography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

In Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight (2015), a criminal masquerading as the local hangman reflects upon the vexed nature of American justice. Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth) first explains how ‘civilised society’ defines justice: the accused is tried by a jury and, if found guilty, a ‘dispassionate’ official carries out the sentence. Mobray then presents the idea of ‘frontier justice’, when people take the law into their own hands, playing judge, jury and executioner. He explains that ‘the good part about frontier justice is it's very thirst quenching. The bad part is it's apt to be wrong as right.’ Mobray's comments prove ironic for the film in question since several characters manipulate ‘civilised’ justice in order to carry out the ‘frontier’ kind. However, they also speak to Tarantino's post-9/11 body of work, films that offer the satisfactions of ‘frontier justice’ by depicting the film's oppressors brought to a violent ending commensurate with their crimes. And yet, while his revenge fantasies do appease our desire to see the bad guys ‘get theirs’, they also ask viewers to recognise ‘the impossibility of a “just” equilibrium’ (Schlipphacke 2014: 114), especially given a filmic formula that achieves ‘its ends when it reveals its own failure, its inability to produce equilibrium in an unjust world’ (123). By cultivating and then compromising the desire for vengeful justice, Tarantino's films invite audiences to interrogate the ways that moral definitions and ideas of justice shift, mutate, evolve, but also fail in a post-modern, now a post- 9/11, culture. His most politically charged films – Inglourious Basterds (2009), Django Unchained (2012) and The Hateful Eight – must be understood as both products of, and inquiries into, a post-9/11 America in which the desire to see those who deserve it ‘get theirs’ has undergirded everything from cultural fictions and media representations to debates about ‘appropriate’ interrogation methods and domestic/foreign policy.

In what follows I deconstruct Tarantino's ‘moral vision’ vis-à-vis justice, arguing that while his works are often disturbingly humorous, their post-modern play with morality is quite serious.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- American Cinema in the Shadow of 9/11 , pp. 169 - 190Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017