Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Maps, Figures & Illustrations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Becoming Maasai: Introduction

- III Being Maasai: Introduction

- 7 Becoming Maasai, Being in Time

- 8 The World of Telelia: Reflections of a Maasai Woman in Matapato

- 9 'The Eye that Wants a Person, Where Can It Not See?': Inclusion, Exclusion, and Boundary Shifters in Maasai Identity

- 10 Aesthetics, Expertise, and Ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai Perspectives on Personal Ornament

- IV Contestations and Redefinitions: Introduction

- V Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

8 - The World of Telelia: Reflections of a Maasai Woman in Matapato

from III - Being Maasai: Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 August 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Maps, Figures & Illustrations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Becoming Maasai: Introduction

- III Being Maasai: Introduction

- 7 Becoming Maasai, Being in Time

- 8 The World of Telelia: Reflections of a Maasai Woman in Matapato

- 9 'The Eye that Wants a Person, Where Can It Not See?': Inclusion, Exclusion, and Boundary Shifters in Maasai Identity

- 10 Aesthetics, Expertise, and Ethnicity: Okiek and Maasai Perspectives on Personal Ornament

- IV Contestations and Redefinitions: Introduction

- V Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

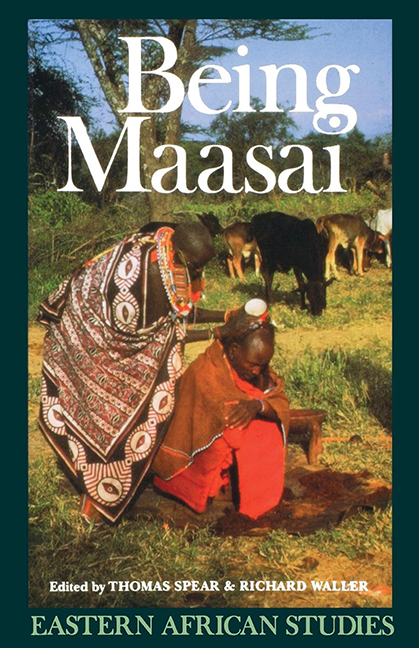

Telelia expressed her world-view on which the present chapter is based towards the end of 1976, It was the most critical period of a severe drought made worse by the spread of East Coast Fever along their herds which killed off most of the calves. I had begun my fieldwork among the Matapato Maasai at the village where Telelia's husband, Masiani Ole Chieni, had three wives. She was the fourth and most senior wife, who was living at the time at a warrior village (manyata. pi. many at) four miles away. This was one of three self-governing manyat set up in Matapato, ostensibly to defend the herds in the area, but serving also to separate young men, murran, temporarily from their fathers. Several years earlier, Telelia had been taken away by the murran of the manyata to accompany her youngest son and a foster nephew along with other selected mothers of murran. No-one could visit the manyata without first obtaining permission from the murran there. Telelia's oldest son Kinai ('Nasira's father’) negotiated this permission for me and it was with him that I first met Telelia inside her hut at the manyata. She was slightly built, although with a resilient vigour in her conversation and movements that gave few concessions to ageing or to hunger caused by the drought. On her shaved head there was just a hint of grey stubble, and her face showed strong, lined features with an extraverted expression. She seemed to merge easily into the company of the other women there, all displaying a string of beads from one ear that identified them as manyata mothers. Telelia was probably the oldest among them. From comments in her narrative, she would have been about 63 years old.

I next met her back at her husband's village as the drought became steadily worse and food became scarcer. Masiani himself had just moved away with one of his wives and the bulk of his herd in the hope of finding better conditions for the cattle elsewhere.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Being MaasaiEthnicity and Identity in East Africa, pp. 157 - 173Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 1993