Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Cartography

- 1 Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg

- Section A The macro trends

- Section B Area-based transformations

- Section C Spatial identities

- 23 Footprints of Islam in Johannesburg

- 24 Being an immigrant and facing uncertainty in Johannesburg: The case of Somalis

- 25 On ‘spaces of hope’: Exploring Hillbrow's discursive credoscapes

- 26 The Central Methodist Church

- 27 The Ethiopian Quarter

- 28 Urban collage: Yeoville

- 29 Phantoms of the past, spectres of the present: Chinese space in Johannesburg

- 30 The notice

- 31 Inner-city street traders: Legality and spatial practice

- 32 Waste pickers/informal recyclers

- 33 The fear of others: Responses to crime and urban transformation in Johannesburg

- 34 Black urban, black research: Why understanding space and identity in South Africa still matters

- Contributors

- Photographic credits

- Acronyms

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Index

24 - Being an immigrant and facing uncertainty in Johannesburg: The case of Somalis

from Section C - Spatial identities

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Cartography

- 1 Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg

- Section A The macro trends

- Section B Area-based transformations

- Section C Spatial identities

- 23 Footprints of Islam in Johannesburg

- 24 Being an immigrant and facing uncertainty in Johannesburg: The case of Somalis

- 25 On ‘spaces of hope’: Exploring Hillbrow's discursive credoscapes

- 26 The Central Methodist Church

- 27 The Ethiopian Quarter

- 28 Urban collage: Yeoville

- 29 Phantoms of the past, spectres of the present: Chinese space in Johannesburg

- 30 The notice

- 31 Inner-city street traders: Legality and spatial practice

- 32 Waste pickers/informal recyclers

- 33 The fear of others: Responses to crime and urban transformation in Johannesburg

- 34 Black urban, black research: Why understanding space and identity in South Africa still matters

- Contributors

- Photographic credits

- Acronyms

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Index

Summary

In this chapter I discuss the influence of urban setting and spatiality on various aspects of Somali identity (social, economic and religious). I describe different categories of Somali immigrants, who continue to face levels of uncertainty and risk in their new host country and particularly in the city-region of Johannesburg. The categories described relate to immigrant status, gender, class and religious identity, and I show how these are important in the stratification of the Somali population living and working in the suburb of Mayfair in Johannesburg. In particular, I look at how intermingling notions of class and immigrant status have contribtued to structuring the economic spatiality that Somali entrepreneurs have formed through a nexus of links between the city of Johannesburg and townships in the Gauteng region.

My-gration, your-gration: who are the Somalis in Johannesburg?

In the field of transnationalism Somali migrants constitute what we call a diaspora – a diaspora whose members have through transnational mobility created a Somali diasporic space on different continents. The diasporic mobility of Somalis is not new, especially for sailors employed in sea ports of the British Empire (Hyslop 2009). As a result, small Somali communities – especially Isaq communities – can be found in port cities as far apart as Perth and New York (Lewis 1961). By the end of the nineteenth century, the biggest Somali presence outside Africa was settled in England along the Welsh coast: these were the seamen of the British Merchant Navy. During the 1930s, Somali leaders in Britain served as political intermediaries for Kenyan Somalis, who tried to negotiate with the Colonial Office in London about uplifting their racial status in Kenya (Turton 1972). There are a number of cases of Somali transnationalism in Africa and elsewhere during imperial and colonial times, as well as after the Second World War. Somalis travelled into southern African countries such as Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to work as miners; they were also present in Yemen and the Gulf states after Somalia's independence, where they were able to organise trans-Indian Ocean business.

Therefore, it is no surprise to observe a stratification of identities among Somalis in post-apartheid South Africa along specific transnational experiences and journeys.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

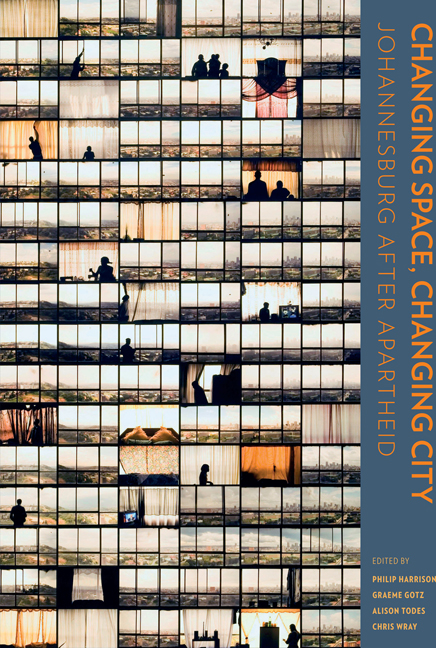

- Changing Space, Changing CityJohannesburg after apartheid, pp. 481 - 486Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014