Introduction

For much of the twentieth century, Upper Palaeolithic (UP) primary burials were seen as a cultural innovation directly stemming from the spread of anatomically modern humans across Europe and strictly associated with the panoply of critical inventions that followed this peopling event (cave and mobiliary art, personal ornaments, blade technology, bone and antler technology, systematic use of pigments, and musical traditions). They were used, in this context, to support the scenario of a cognitive revolution occurring in Europe ca. 40,000 BP (Klein Reference Klein2000; Mellars & Stringer Reference Mellars and Stringer1989). Neanderthal burials from Europe and western Asia were in the framework of this scenario discarded as the outcome of natural phenomena, considered unreliable because of the antiquity of excavations, interpreted as revealing a much lesser degree of complexity, or seen as reflecting a qualitatively different cognition (see Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011; Sandgathe et al. Reference Sandgathe, Dibble, Goldberg and McPherron2011; Zilhão, this volume, for a review of the debate). We argue in this chapter that this view is no longer tenable and will demonstrate that ensuant paradigm changes, methodological innovations, and new dating allow researchers to apply a novel research philosophy to UP mortuary practices. In particular we will use available 14C dates to test the unitarian character of the UP burial phenomenon, explore the potential of grave goods associated with Gravettian primary burials to reconstruct cultural geography, and use results from the direct analysis of grave goods associated with some UP primary burials to evaluate the degree of social inequality present in Palaeolithic societies.

The first reason for challenging the ‘sapiens-burial’ equivalence is linked to the observation that chimps, to some extent, do it too. Although inhumation and treatment of the dead are generally regarded as quintessential features of modern humanity, carrying of infant corpses – in one case for sixty-eight days – and attention paid to corpses of adults have been reported for a number of primates in the wild (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Gillies and Lock2010; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Piel and O’Malley2012; Piel & Stewart, this volume). We do not know the meaning of these practices and whether they are symbolic in nature, but they suggest that chimpanzees may have a greater awareness of death and dying than previously thought. These practices suggest that chimps’ and humans’ common ancestor, and subsequent members of the human lineage, may have shared a concern for the demise of their body. The inevitable corollary of this observation is that mortuary practices can no longer be seen as an exclusive sapiens business, but represent instead an inherent feature of the behavioural evolution of our lineage. This may have gone through a number of evolutionary steps reflecting patterns of cognitive evolution (Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011) or manifested itself through variability in time and space reflective of different cultural and social settings. Some of the oldest instances of mortuary behaviour have left archaeological traces, which make evolutionary models concerning mortuary practices testable (see Zilhão, this volume).

The second reason for not considering UP burials as a monolithic hallmark of ‘modernity’ is that archaeological discoveries made during the last decade have challenged the ‘Human Revolution’ paradigm. We now know that the emergence of humanness, including aspects related to death, can no longer be conceived in antonymic terms. During the period between 160 ka and 20 ky BP, complex lithic technology, adaptation to hostile environments, engravings, pigments, personal ornaments, and elaborated bone technology appear, disappear, and reappear in different forms, suggesting major discontinuities in cultural transmission (d’Errico & Stringer Reference d’Errico and Stringer2011). The discontinuous nature in time and space of this process, and the fact that this trend is common to modern humans in Africa and Neanderthals in Europe suggests that local conditions must have played a role in the emergence, diffusion, and eventual disappearance of crucial innovations or particular cultural choices in the different regions of the world. This contradicts a stochastic scenario for the origin of the modern behavioural ‘package’. It also counters the gradualist ‘Out of Africa’ model according to which we should see the crucial cultural innovations that have made our species culturally modern occurring only in that continent and gradually accumulating there as a result of the origin of our species. There is no reason to think that beliefs and acts concerning death did not undergo a similar process. Data on early mortuary practices in Africa and Europe are particularly telling in this respect (see Zilhão, this volume, for a review of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic evidence). Instead of finding, as one might expect, increasingly complex mortuary practices including primary inhumations, associated with the Middle Stone Age in Africa, we observe a patchy pattern that does not fit the model. The claim for a polish suggestive of curation of a skull at the ca.-160,000-year-old site of Herto in Ethiopia has not been supported by additional data (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Beyene, WoldeGabriel, Hart, Renne, Gilbert, Defleur, Suwa, Katoh, Ludwig, Boisserie, Asfaw and White2003). Similarly, the first consistent evidence for a primary burial tradition is found in western Asia (at sites such as Skhul, Qafzeh, and Tabun) and not Africa, is a behaviour shared by early modern humans and Neanderthals (Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011), and appears much later than the date suggested by palaeoanthropologists and geneticists for the origin of our species in Africa. In addition, we do not observe this practice again in modern humans for more than 40,000 years. Only three Middle Stone Age burials are known, that of the Border Cave (Beaumont et al. Reference Beaumont, de Villiers and Vogel1978) with an age of 74,000 BP, and those of Nazlet Khater (Crevecoeur Reference Crevecoeur2006) and Taramsa, Egypt (Van Peer et al. Reference Van Peer, Vermeersch and Paulissen2010) dated to 40,000 and 68,000 BP respectively. The child from Border Cave is associated with a perforated Conus sp. shell, and one of the three individuals from Nazlet Khater has a biface close to the head. In sum, if burial practices leaving a trace in the archaeological record were seen as an indication of cultural modernity, the African evidence would hardly receive a passing grade.

This is more significant when considering that after a period of mistrust and intense debate exemplified by Gargett’s critical approach to the issue (Gargett Reference Gargett1999), most Palaeolithic archaeologists (but see Sandgathe et al. Reference Sandgathe, Dibble, Goldberg and McPherron2011) have changed their view on Neanderthal burials. Among the sixty Middle Palaeolithic primary and possibly secondary burials reported from Europe and western Asia, at least forty belong to Neanderthals. Neanderthal burials in Europe are numerous, but concentrated in a few areas, suggesting that Neanderthals, as modern humans in Africa, often may have engaged in funerary practices that left no archaeological signature. Although in a number of cases this information is now difficult to verify, grave goods consisting of stone tools, bone retouchers, engraved bone, and a rock slab engraved with cupules were reported at Neanderthal burials such as La Ferrassie, La Chapelle-aux-Saint, and Le Moustier in France, as well as Amud and Dederiyeh in the Middle East (Maureille Reference Maureille2004; Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011). New evidence indicates that Neanderthals may also have deliberately modified and used human bone. Research conducted by one of us has recently shown that the oldest known human bone used as a tool is a fragment of Neanderthal skull from La Quina in the Charente region of France (Verna & d’Errico Reference Verna and d’Errico2011). Two human skull fragments found close to the bone tool, probably from the same individual, show traces of percussion, cutting, and scraping marks consistent with the hypothesis that the knapper cleaned the skull when soft tissues were still present, broke it, and subsequently selected the bone fragment s/he wished to use as a tool. This suggests that the knapper was aware s/he was using a human bone. The Neanderthal evidence and in particular its consistent variability in time and space shows that there may be no clear-cut boundary between the Middle and the UP and little, if any, between the Middle and the Later Stone Age but rather a non-linear process consisting of continuity in local traditions interrupted by choices of mortuary practices that are archaeologically invisible. There is no reason to believe that the pattern of change observed in the Middle Palaeolithic (and in most historically known human societies) should not also be at work in the UP.

Most of the partisans of the ‘Human Revolution’ scenario perceived UP burials as a unitary phenomenon, reflecting a threshold in cognition and representing a crucial step in the evolution of the way human societies conceived of death and the afterlife. By revealing that the history of mankind has long been dominated by non-linear cultural evolution, probably triggered by environmental changes and ensuing impacts on population dynamics, the new paradigm encourages a more in-depth analysis of UP burials in search of patterns of synchronic and diachronic variability that may signal changes in the way UP societies perceived death and that can tell us something about UP societies themselves. After all, cross-cultural analysis of mortuary practices, including those of hunter-gatherers, reveals an astonishing variability in the way the dead are treated (Binford Reference Binford1971; Testart Reference Testart2001). Why should we expect to find different trends during a period of more than 20,000 years and over a region covering more than 10 million square kilometres? The identification of a spatial and chronological continuity in UP mortuary practices would paradoxically contradict rather than confirm the modern character of UP cultural systems as it would make of such practices, seen as a whole, an evolutionary step of our lineage’s cognitive trajectory, a step characterised by a much lower degree of variability than the one observed historically. Direct dating of primary burials (e.g., Formicola et al. Reference Formicola, Pettitt and Del Lucchese2004; Kuzmin et al. Reference Kuzmin, Burr, Jull and Sulerzhitsky2004; Dobrovolskaya et al. Reference Dobrovolskaya, Richards and Trinkaus2012; Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011) and methodological innovations in the analysis of grave goods now place this goal within our reach. The former has played a major role in the last decade in reassessments of the age of a number of UP primary burials recorded decades ago and traditionally attributed to specific techno-complexes on the basis of often-uncertain stratigraphic evidence and associated grave goods. Many of these burials, and particularly those attributed to the Aurignacian, have been found to be much younger and in some cases not even Palaeolithic in age (Grootes et al. Reference Grootes, Smith and Conard2004; Street et al. Reference Street, Terberger and Orschiedt2006; Tiller et al. Reference Tiller, Mester, Bocherens, Henry-Gambier and Pap2009; Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffmann, Hublin, Hüls and Terberger2011). When confirming the traditional attribution, direct dating has significantly refined our knowledge of the age of the burial and identified possible inconsistencies with previous indirect dates. Although problems remain, databases of direct and indirect 14C ages for UP burials can now be constructed and explored (see d’Errico et al. Reference d’Errico, Banks, Vanhaeren, Laroulandie and Langlais2011) with the aim of identifying consistencies in UP mortuary practices through both time and space.

In parallel with such advances, a number of studies have highlighted the potential of personal ornaments, in particular those associated with primary burials, as a means of addressing issues of past cultural geography and social inequality. Ethnographic studies have shown that beadwork, like body painting, scarification, tattooing, garments, and headdresses, is perceived by members of traditional societies as a powerful indicator of identity, enhancing intra-group cohesion and fixing boundaries with neighbouring groups (Strathern & Strathern Reference Strathern and Strathern1971; Faris Reference Faris1972; Ray Reference Ray1975; Hodder Reference Hodder1977, Reference Hodder1982; Lock & Symes Reference Lock, Symes, Lock and Peters1999; Sanders Reference Sanders2002; Verswijver Reference Verswijver1986; Kuhn & Stiner Reference Kuhn and Stiner2007; Vanhaeren Reference Vanhaeren2010). Ethnographic studies also indicate that the ethnic dimension of beadwork is conveyed through the use of distinct bead types or by particular combinations and arrangements of bead types on the body shared with one or more neighbouring groups. Since the other functions of personal ornaments –that is, markers of gender, age, class, wealth, social status, or use as exchange media, and so on – are governed by rules shared by the members of a community, beadwork used in these ways also contributes, even if unintentionally, to differentiate a society from a neighbouring one (Vanhaeren Reference Vanhaeren, d’Errico and Backwell2004). As a consequence, we may expect that contemporaneous cultural entities will be identified archaeologically by geographically coherent clusters of sites yielding particular ornament types as well as by characteristic proportions and associations of types found over broad regions. Archaeologically, this research strategy seems appropriate: personal ornaments are associated with most UP technocomplexes and they occur during this period as many distinct types. We have created a geospatial database recording the occurrence of 157 bead types at ninety-eight Aurignacian sites (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren2006). Seriation, correspondence, and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) analyses of these data identified a definite cline in ornament type association sweeping counter-clockwise from the northern European plains to the eastern Alps via western and southern Europe through fourteen geographically cohesive sets of sites. We have argued that this pattern, which is not solely explained by chronological differences between sites or raw material availability, reflects long-lasting ethno-linguistic diversity of Aurignacian populations. To date the potential of this approach has not been tested by a comparable analysis of beads associated with primary burials. This is one of the goals of the present study.

Ethnicity, however, constitutes only one element in the construction of social identities and is one of many that may be reflected in mortuary practices. In the last few years, ethnographers have explored mortuary practice variability with the aim of identifying consistencies that may suggest middle range theories to guide the interpretation of graves of mute past societies (Testart Reference Testart2006). Results from such cross-cultural research revealed that in many instances grave goods may indeed inform us about the degree of social inequality of a given society and can provide insights into the way ideology and power influenced the possession and sharing of goods.

On the other hand, advances in analytical methods applied to the study of grave goods associated with prehistoric burials, in particular personal ornaments, have significantly increased the quality and quantity of information on which archaeologists can rely to interpret this record (Giacobini & Malerba Reference Giacobini, Malerba, Hahn, Menu, Taborin, Walter and Widemann1995; White Reference White and Camps-Fabrer1999; d’Errico & Vanhaeren Reference d’Errico, Vanhaeren, Cupillard and Richard2000, Reference d’Errico2002; Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren and d’Errico2001, Reference Vanhaeren2003a, Reference Vanhaeren, Larsson, Kindgren, Knutsson, Leoffler and Akerlund2003b, Reference Vanhaeren, Zilhão and Trinkaus2003c, Reference Vanhaeren2005; Vanhaeren et al. Reference Vanhaeren, d’Errico, Billy and Grousset2004; d’Errico & Vanhaeren Reference d’Errico2002; Bonnardin Reference Bonnardin2009; Rigaud et al. Reference Rigaud, Errico, Vanhaeren and Vidal Encinas2010, Reference Rigaud, Vanhaeren, Queffelec, Le Bourdon and d’Errico2014; Slimak & Plisson Reference Slimak and Plisson2008; Cristiani & Borić Reference Cristiani and Borić2012). Grave goods associated with primary burials are well suited to provide more precise data on the social status of the deceased. One can be certain that the types of beads (raw material, colour, species, shape, size, and so on) found and their manufacturing techniques were all part of the material culture of the mourners or the societies with which they were in contact. By combining taphonomic, archaeozoological, isotopic, morphometric, technological, and functional data and comparing them with dedicated natural and experimental reference collections, archaeologists can now gather valuable information on the origin, modification techniques, stringing, length of use, and other aspects of ornaments associated with burials. Such information is of great relevance in establishing, for example, the local versus exotic provenance of objects, in assessing the degree of craft specialization necessary for their production, and in identifying whether they represent offerings deposited in the grave or objects worn by the deceased during his or her lifetime. If offerings are taken as items that will facilitate the journey of the deceased after death, that will be used during the afterlife, and that signal a belief in a form of immortality, the methods with which we have experimented so far may contribute to the identification of such belief systems.

In a series of papers (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren and d’Errico2001, Reference Vanhaeren2003a, Reference Vanhaeren, Larsson, Kindgren, Knutsson, Leoffler and Akerlund2003b, Reference Vanhaeren2005; Vanhaeren et al. Reference Vanhaeren, d’Errico, Billy and Grousset2004), we have argued that the application of these methods to grave goods associated with individual burials and their comparison with ornaments and faunal assemblages from contemporary sites and burials may provide a means with which one can assess the degree of social inequality present in Palaeolithic societies.

The aim of this contribution is to combine the analysis of a georeferenced database of grave goods associated with UP primary burials, their 14C ages, and results from the direct analysis of grave goods from a number of burials to understand the way in which these societies dealt with death. Our analysis highlights marked discontinuities through time as well as spatial consistencies that reflect ethnic and social identities at a regional scale.

Methods

In order to investigate the geographic and chronological distribution of UP primary burials, we created a database including their geographic coordinates and 14C ages using a variety of sources (Binant Reference Binant1991; Dobrovolskaya et al. Reference Dobrovolskaya, Richards and Trinkaus2012; Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren and d’Errico2001, Reference Vanhaeren, Zilhão and Trinkaus2003c; Formicola et al. Reference Formicola, Pettitt and Del Lucchese2004; Giacobini Reference Giacobini2006; Henry-Gambier Reference Henry-Gambier, Vialou, Renault-Miskovsky and Patou-Mathis2005, Reference Henry-Gambier2008; d’Errico et al. Reference d’Errico, Banks, Vanhaeren, Laroulandie and Langlais2011; Pettitt Reference Pettitt2011 and references therein; Marom et al. Reference Marom, McCullag, Higham, Sinitsyn and Hedges2012). Whenever possible, information was cross-checked against recent re-appraisals of burial sites. A number of purported burials were excluded from the database either because their burial status is questioned or because their chronological attribution remains uncertain. The former is the case with the Marronnier child remains, and the latter with the Combe Capelle and Labattut burials.

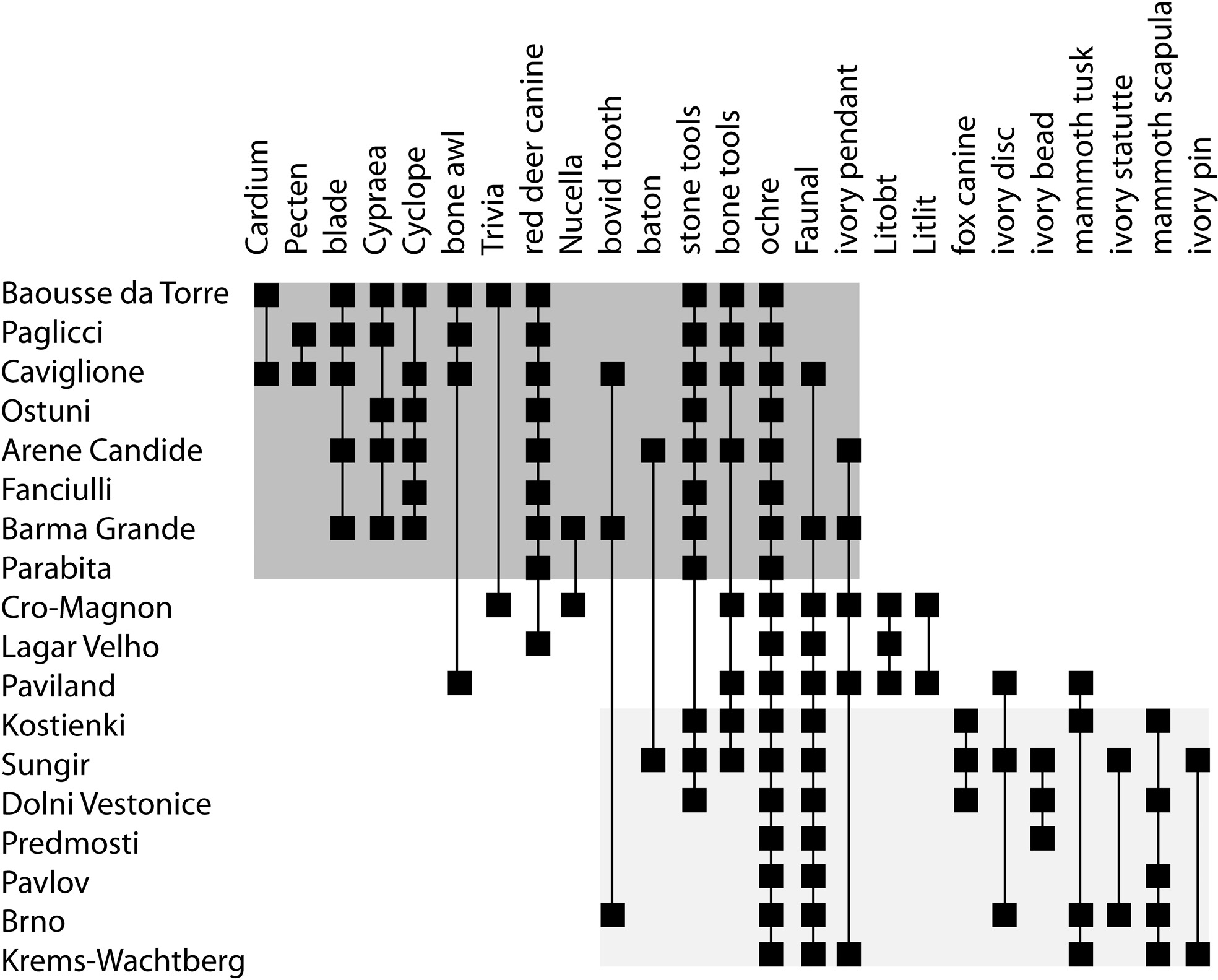

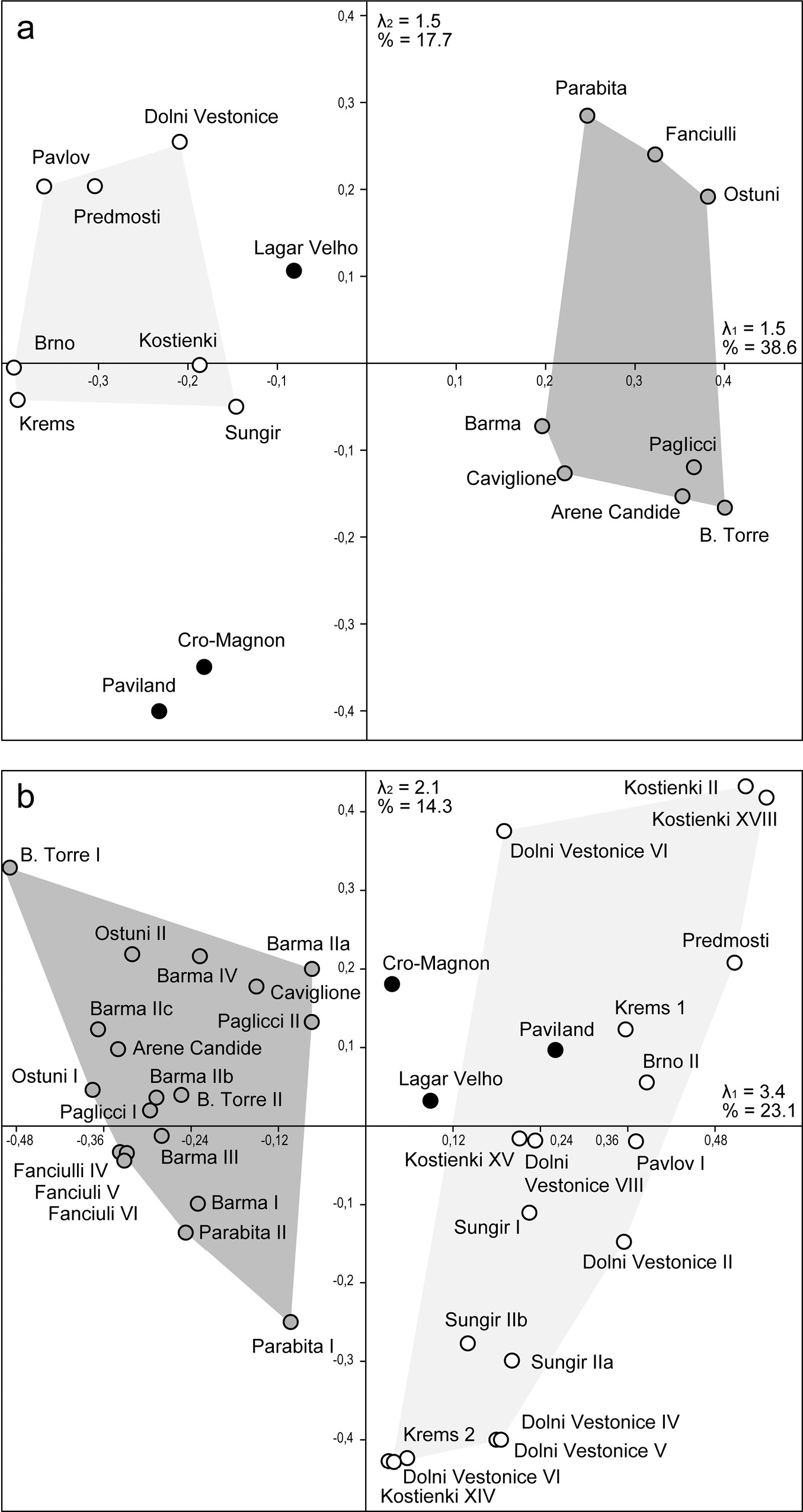

To test the potential of UP grave goods for identifying ethnocultural diversity, a second database was constructed for the grave goods associated with Gravettian burials. We considered objects’ raw material, function, morphology, and, in the case of personal ornaments, shell genus, and tooth species and type. These attributes were combined in order to create mutually exclusive grave goods categories. Data from single burials and burial sites were submitted to a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), and an unconstrained seriation of the absence-presence matrix. Grave good types present only at a single burial were excluded from the study. We used the statistical package PAST (Hammer & Harper Reference Hammer and Harper2006) to perform these analyses.

In the last fifteen years we have directly analysed the grave goods associated with a number of Middle and UP burials and developed methods to characterise the provenance of the raw material, manufacturing, and stringing techniques as well as use wear. These include the sites of Skhul, Border Cave, Bausso da Torre, Paglicci, Cro-Magnon, Lagar Velho, Saint-Germain-la-Rivière, La Madeleine, Les Enfants, and Aven des Iboussières. Although only some of the results are published, we take those observations into account in our discussion of the burial record.

Results

Chronology

At least 195 UP and Epipalaeolithic primary burials, discovered at sixty-one European sites, are reported in the literature. Most of the sites only have one or two individual burials. Multiple burials do exist but they are uncommon. All age classes and both sexes are represented. Sites with primary burials are not evenly distributed in space or time. Seventy percent of the primary burials are located in France and Italy. Only 17 percent of the UP burials are directly or indirectly dated by conventional or AMS 14C (Tables 4.1–4.2). Analysis of these ages reveals that reliable primary inhumations are virtually absent during the more ancient phases of the UP, corresponding in western Europe to the so-called Proto-Aurignacian and Ancient Aurignacian. They fall into three temporal clusters separated by gaps of at least 2000 years (Figure 4.1). The oldest cluster, dated between 35,000 and 27,000 calibrated (cal) BP, includes a large number of burials attributed to the Gravettian (Figure 4.2) and contemporaneous cultural facies (Pavlovian and Sungirian). These burials are present across Europe (Figure 4.3).

Table 4.1. Indirect 14C radiocarbon ages of Upper Palaeolithic burials

| Site | 14C age BP | ±1 σ error | Laboratory code | Figure 4.1 (top) number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kostienki 1 Poliakov | 32600 | 1100 | OxA-7073 | 1 |

| Cavillon | 28780 | 560 | GifA-88202 | 2 |

| Cro-Magnon | 27680 | 270 | Beta-157439 | 3 |

| Dolni Vestonice triple | 26640 | 110 | GrN-14831 | 4 |

| Krems-Wachtberg | 26520 | 200 | VERA-3819 | 5 |

| Pavlov | 26400 | 110 | GrN-1272 | 6 |

| Dolni Vestonice 16 male | 26390 | 270 | ISGS-1744 | 7 |

| Pavlov | 26170 | 450 | GrN-20391 | 8 |

| Dolni Vestonice 4 child | 25950 | 630 | GrN-18189 | 9 |

| Dolni Vestonice 3 female | 25950 | 630 | GrN-18189 | 10 |

| Predmosti | 25820 | 170 | GrN-1286 | 11 |

| Dolni Vestonice 16 male | 25740 | 210 | GrN-15277 | 12 |

| Dolni Vestonice 16 male | 25570 | 280 | GrN-15276 | 13 |

| Dolni Vestonice triple | 24970 | 920 | ISGS-1617 | 14 |

| Lagar Velho | 24860 | 200 | GrA-13310 | 15 |

| Pavlov | 24800 | 150 | GrN-1325 | 16 |

| Barma Grande triple | 24800 | 800 | OxA-10093 | 17 |

| Barma Grande 5 | 24800 | 800 | OxA-10093 | 18 |

| Barma Grande 1 | 24800 | 800 | OxA-10093 | 19 |

| Paglicci | 24720 | 420 | F-55 | 20 |

| Lagar Velho 1 | 24660 | 260 | OxA-8421 | 21 |

| Lagar Velho | 24520 | 240 | OxA-8423 | 22 |

| Ostuni | 24410 | 320 | Gif-9247(1) | 23 |

| Dolni Vestonice triple | 24000 | 900 | ISGS-1616 | 24 |

| Lagar Velho | 23920 | 220 | OxA-8422 | 25 |

| Paglicci | 23040 | 380 | F-51 | 26 |

| Parabita | 22220 | 360 | na | 27 |

| Parabita | 22110 | 330 | na | 28 |

| Pataud | 22000 | 980 | OxA162/GrN1876 | 29 |

| Malta | 19880 | 160 | Oxa-7129 | 30 |

| Tagliente | 13270 | 170 | OxA3532 | 31 |

| Tagliente | 13070 | 70 | OxA-35313 | 32 |

| Koneprusy | 12870 | 70 | GrA-13696 | 33 |

| Fanciulli 3 | 12200 | 400 | MC-402 | 34 |

| Vado all’Arancio | 11600 | 130 | Ly-3415 | 35 |

| Vado all’Arancio | 11330 | 50 | R-1333 | 36 |

| Romito | 11150 | 150 | R-300 | 37 |

| Romito | 10960 | 950 | R-221 | 38 |

| Maritza | 10420 | 60 | R-1270-R | 39 |

| Aven des Iboussieres | 10210 | 80 | OxA-5682 | 40 |

Note: na: not available.

Table 4.2. Direct 14C radiocarbon ages of Upper Palaeolithic burials

| Site | 14C age BP | ±1 σ error | Laboratory code | Figure 4.1 (bottom) number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kostienki 14 Markina Gora | 33250 | 500 | OxA-X-2395–15 | 1 |

| Sungir 2 | 30100 | 550 | OxX-2395–6 | 2 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 30000 | 550 | OxX-2395–7 | 3 |

| Paviland | 29490 | 210 | OxA-16413 | 4 |

| Paviland | 28870 | 180 | OxA-16412 | 5 |

| Sungir 2 early adolescent | 27210 | 710 | AA-36474 | 6 |

| Sungir 1 adult male | 27050 | 210 | KIA-27006 | 7 |

| Villehonneur | 27010 | 210 | Beta-216141 | 8 |

| Villehonneur | 26690 | 190 | Beta-216142 | 9 |

| Paviland | 26350 | 550 | OxA-1815 | 10 |

| Sungir 2 early adolescent | 26200 | 640 | AA-36475 | 11 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 26190 | 640 | AA-36476 | 12 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 26000 | 410 | KIA-27007 | 13 |

| Paviland | 25840 | 280 | OxA-8025 | 14 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 25430 | 160 | OxA-15751 | 15 |

| Cussac 1 | 25120 | 120 | Beta-156643 | 16 |

| Sungir 2 | 25020 | 120 | OxA-15753 | 17 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 24830 | 110 | OxA-15754 | 18 |

| Barma Grande 6 | 24800 | 800 | OxA-10093 | 19 |

| Ostuni 1 | 24410 | 320 | Gif-9247 | 20 |

| Sungir 3 late juvenile | 24100 | 240 | OxA-9038 | 21 |

| Sungir 2 early adolescent | 23830 | 220 | OxA-9037 | 22 |

| Brno 2 | 23680 | 200 | OxA-8293 | 23 |

| Arene Candide Principe | 23440 | 190 | OxA-10700 | 24 |

| Kostienki 8 Telmanskaia | 23020 | 320 | OxA-7109 | 25 |

| Sungir 1 adult male | 22930 | 200 | OxA-9036 | 26 |

| Kostienki 18 | 21020 | 180 | OxA-7128 | 27 |

| Sungir 1 adult male | 19160 | 270 | AA-36473 | 28 |

| Saint-Germain-la-Rivière | 15780 | 200 | GifA-95456 | 29 |

| Laugerie-Basse | 15660 | 130 | GifA-94204 | 30 |

| Lafaye | 15290 | 150 | GifA-95047 | 31 |

| Wilczyce | 12870 | 60 | OxA-16729 | 32 |

| Bonn Oberkassel female | 12180 | 100 | OxA-4792 | 33 |

| Villabruna | 12140 | 70 | KIA-27004 | 34 |

| Neuwied Irlich neonate | 11965 | 65 | OxA-9848 | 35 |

| Neuwied Irlich adult | 11910 | 70 | OxA-9847 | 36 |

| Bonn Oberkassel male | 11570 | 100 | OxA-4790 | 37 |

| Roc-de-Cave | 11210 | 140 | GifA-95047 | 38 |

| Fanciulli double | 11130 | 100 | GifA-94197 | 39 |

| Arene Candide XIV | 10735 | 55 | OxA-11003 | 40 |

| Arene Candide XII | 10720 | 55 | OxA-11002 | 41 |

| Arene Candide VIII | 10655 | 55 | OxA-11001 | 42 |

| Arene Candide VIb | 10585 | 55 | OxA-11000 | 43 |

| Madeleine | 10190 | 100 | GifA-95457 | 44 |

| Arene Candide III | 10065 | 55 | OxA-10998 | 45 |

| Arene Candide Vb | 9925 | 50 | OxA-10999 | 46 |

Figure 4.1. Available indirect (top) and direct (bottom) calibrated 14C dates for Upper Palaeolithic primary burials (cf. Tables 4.1 and 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Examples of Gravettian and contemporary primary burials.

a: Sungir, Russia;

b: Arene Candide, Italy;

c-d: Dolni Vestonice;

e-f: Lagar Velho;

h: Paglicci;

g and i: perforated red deer canines associated with the Lagar Velho and Paglicci, respectively.

Figure 4.3. Geographical distribution of dated Gravettian sites (dots) and primary burials (crosses).

The second cluster includes three sites from southwestern France attributed to the Ancient Magdalenian and dated to ca. 19,000 cal BP. The third cluster is situated between 15,000 and 12,000 cal BP and includes Epigravettian burials from Italy, two Magdalenian burial sites from France, and a Magdalenian site from the Czech Republic.

Grave Goods Associated with Gravettian Burials

Multivariate analyses of grave goods associated with Gravettian burials reveal a clear difference between sites in the Italian peninsula and those from eastern Europe, and a possible third intermediate entity represented by sites in England, southwestern France, and Portugal (Figures 4.4–4.5). Interestingly, similar results are obtained irrespective of whether all grave goods found at a burial site (Figure 4.5a) or just those associated with individual burials (Figure 4.5b) are considered in the analyses.

Figure 4.4. Seriation of grave goods associated with Gravettian burial sites.

Figure 4.5. Principal coordinate analysis of grave goods associated with Gravettian burial sites (a) and with individual burials (b).

The Italian burials have in common the widespread use of shells as personal ornaments. Twenty different species of gastropoda and bivalvia were found in these burials, and two of them (Cyclope sp. and Cypraea sp.) are, respectively, associated with thirteen and seven of the twenty interments from this region. In contrast, perforated shells are rarely associated with earlier UP burials from northeastern Europe, and, when they are, we find species unknown in the southern sample, such as Dentalium sp. in Brno 2. Another dissimilarity appears in the choice of teeth for pendants. Fifteen of the twenty southern interments yielded red deer canines, absent in the northeastern burials. The latter shows instead a frequent use of fox canines, never found associated with Gravettian burials from the Italian peninsula. Stone pendants and perforated discs are another feature that characterises northern burials. The Italian interments are instead characterised by an abundance of knapped stone tools, rare among burials of the other group. A disparity between the two groups of burials also appears in the use of personal ornaments and tools made of ivory. The presence of ivory objects in the Italian burials is limited to the pendants found at Arene Candide and Barma Grande. A large variety of personal ornaments and tools made from ivory is instead associated with contemporary burials from northern and eastern Europe. Faunal remains are restricted in the southern group to an ibex mandible and a horse maxilla associated with one of the two Paglicci burials, a bovid long bone at Barma Grande, and an astragalus, and possibly three red deer mandibles, found near the Caviglione 1 skeleton. Mammoth scapulae and rhinoceros ribs as well as rhinoceros, mammoth, and fox skulls have been recovered from interments of the northern group.

The grave goods associated with the burial sites of Cro-Magnon, Paviland, and Lagar Velho are different from both the Italian and the eastern sample. They share the presence of Littorina sp. shell beads, which are not found elsewhere. Paviland and Cro-Magnon ornaments also include ivory beads and pendants similar to those from eastern Europe while the Lagar Velho child is associated with red deer canines, which are present in all Italian burials.

Social Inequality

In hunter–gatherer societies where social inequalities are marked by the possession of riches, wealth comprises objects that display one or more of the following characteristics: (1) rare materials, either by their nature or through remoteness from their point of origin; (2) fabrication requiring a major investment of time and work; (3) production involving complex techniques mastered exclusively by certain members of the group; and (4) standardised forms and colours (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren2005). The first three characteristics ensure some control of the production of the units of value; the last one guarantees the interchangeability of objects of the same value. The ostentatious wearing of ornaments made up of numerous exotic objects obtained by exchange often characterises individuals as belonging to a dominant social group.

Depending on the society, this wealth may be inherited, distributed, exchanged, destroyed, or abandoned in a ritualised way, for example during funerary ceremonies. The abandonment of these goods in the tomb is generally part of a strategy of deliberately removing wealth from the exchange network, which prevents the gradual loss of their value caused by the introduction, through production or exchange, of new objects to the system. In these societies, those individuals who have access to this wealth constitute a minority. Other members may receive small quantities of these goods as loans or gifts, and possess goods of lesser prestige because they are less elaborate or not of exotic origin. Widely diffused within the society, and used by most of its members, these goods should have a better chance of being lost and then incorporated into the archaeological record.

The funerary ceremonies reserved for ‘common people’ can be very different from those of the ‘honourable’ people or may simply constitute a simplified version of them (Testart Reference Testart2006). Cross-cultural studies indicate that belonging to a privileged social group is often marked by the construction of durable mortuary structures.

We have argued elsewhere (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren2005) that as archaeologists, we should be able to identify complex societies through the presence of burials associated with prestige goods and elaborate structures. These burials should either be accompanied by others, without grave goods or with goods of lesser prestige, which can include small quantities of exotic objects, or appear to be the only funerary evidence – a clue indicating that the members of the less privileged groups were subjected to funerary practices that are archaeologically invisible. Additionally, a striking difference should appear when comparing personal ornaments associated with some burials and those found at habitation sites. The latter should mainly feature ornaments made of readily available raw materials and only rarely those found in the richest primary burials.

In other words, the contextualised comparative analysis of grave goods and contemporary personal ornaments found at habitation sites becomes a necessary epistemological requirement to establish whether they can be interpreted as riches.

White (Reference White and Camps-Fabrer1999) interprets as evidence for hereditary social ranking the difference in the number of elaborate grave goods associated with three burials from Sungir, Russia (Figure 4.2a), dated to ca. 30,000 BP (Marom et al. Reference Marom, McCullag, Higham, Sinitsyn and Hedges2012). However, no contextual data (comparison with personal ornaments found at contemporary habitation sites, raw material availability, etc.) are provided to demonstrate that the Sungir grave goods represent riches. Such contextual data and results of an integrated taphonomical, archaeozoological, technological, and morphometrical analysis are lacking for almost all the other UP burials that have yielded grave goods. Exotic grave goods in the form of Atlantic shell beads and mammoth ivory pendants are, for example, found in Gravettian burials from northern Italy. Nevertheless their exceptional character still needs to be demonstrated.

The two unique cases in which the approach promoted here has been applied and the hypothesis of social inequality supported by a range of data are those of the La Madeleine child burial, dated to 10,190 ± 100 BP (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren2003a), and the Saint-Germain-la-Rivière burial, dated to 15,780 ± 200 BP (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren2003a, Reference Vanhaeren2005).

Analysis of the 1,500 shell beads associated with the La Madeleine three-year-old child shows that Epipalaeolithic craftsmen invested a substantial amount of time in the production of tiny versions of adult beads and their embroidery for ostentatious display on the child’s clothing. Strontium isotope dating of Dentalium sp. shells, which represent the large majority of the beads associated with this burial, indicates they were collected on the Atlantic coast, some 200 km from the site (Vanhaeren et al. Reference Vanhaeren, d’Errico, Billy and Grousset2004). As the biological age rules out the possibility that the La Madeleine child achieved a special status through distinguished personal acts, the richness, variety, and specific form of this child’s beadwork either may mark all children as a distinct social grade, as suggested by Zilhão (Reference Zilhão, Vialou, Renault-Miskovsky and Patou-Mathis2005) for all early UP child burials, or may be a result of the child’s integration into a hereditary ranking system.

The excavation of the Saint-Germain-la-Rivière burial revealed a structure comprising four blocks supporting two slabs, which seemed to protect the deceased (Figure 4.6). A rich set of almost one hundred grave goods, including the skull of a bison, bone and stone tools, as well as seventy-one perforated red deer canines accompanied this burial. The virtual absence of red deer in southwestern French faunal assemblages dated to the same period and in the diet of the deceased (Drucker & Henry-Gambier Reference Drucker and Henry-Gambier2005), the preference for teeth from young stags, the rarity of this bead type at the site and at contemporary sites from the same region, together suggest that the teeth were obtained through long-distance trade and represented prestige items. This is confirmed by the analysis of personal ornaments found in the habitation layers of the Saint-Germain-la-Rivière site, which are dominated by beads made of locally available raw material, such as reindeer incisors and phalanges, and their imitations in steatite, fossil urchins, and fox canines. These studies indicate that certain members of Early-Middle Magdalenian societies in southwestern France possessed wealth made up of rare, and probably exotic, ornaments. The use of important quantities of exotic objects, probably implying structured exchange networks, seems to contradict the hypothesis that these objects served to mark individual social roles (such as chief or shaman) and, instead, suggests that their role must have been that of identifying groups made up of several individuals.

Figure 4.6. Personal ornaments associated with the Saint-Germain-la-Rivière Madgalenian primary burial, as well as a photo and reconstruction of the structure protecting the deceased.

Discussion and Conclusion

Geographic distribution and direct 14C dating of primary UP burials contradict the idea that mortuary practices during this period were a unitary phenomenon. Two-thirds of UP burials were discovered in France and Italy. This cannot be solely attributed to the history of research or to differential preservation: some areas such as the Cantabrian coast, rich in Palaeolithic sites and with well-preserved faunal assemblages, have yielded no burials. The heterogeneous distribution probably reflects, as is also arguably the case with Neanderthal burials, the fact that mortuary practices other than primary burials in habitation sites existed in some regions and left no or ambiguous archaeological signatures.

Chronologically, episodes during which interment, at least for some individuals, occurs alternate with periods during which there is an absence of burials in the archaeological record. With just 17 percent of burials directly dated, this pattern may of course change in the future and may be only partially representative of past reality. The absence of primary burials in the Aurignacian, for example, is not conclusive. One burial from Bausso da Torre, apparently associated with a typical split-based point, could well be one of the few primary burials from this period (Vilotte & Henry-Gambier Reference Vilotte and Henry-Gambier2010). Kostienki 14 could be another (Marom et al. Reference Marom, McCullag, Higham, Sinitsyn and Hedges2012). Curatorial attention paid to UP burials, many of which were excavated long ago, represents a supplementary challenge to their accurate dating and may influence the observed pattern in the future. Application of a method based on extraction and AMS 14C dating of hydroxyproline, a bone-specific biomarker, to the Sungir burials has recently shown that the addition of glues and consolidants to human remains kept in museums can significantly rejuvenate their age and that even the more advanced techniques that attempt to eliminate contamination entirely, such as collagen ultrafiltration, can be ineffective (Marom et al. Reference Marom, McCullag, Higham, Sinitsyn and Hedges2012). This probably explains the considerable range – Sungir being a remarkable example – observed in the ages produced at different times and by different laboratories when dating the same burial. It is, however, a fact that the direct dating of the UP burials is narrowing down rather than widening the time spans during which primary burials occurred and increasing the gaps during which no primary burials are found. This suggests that additional radiocarbon ages and methodological improvements will serve better to constrain rather than call into question the observed pattern.

Statistical analyses of Gravettian grave goods identify two, possibly three, spatially cohesive clusters composed of burials that share similar grave good type associations. We argue that the more parsimonious explanation for the observed pattern is that geographic differences in grave goods mirror long-lasting cultural differences between the human groups that lived in these areas between 34,000 and 26,000 cal BP. Alternative interpretations appear unlikely, for a number of reasons. In the light of what is known about Gravettian cultural continuity, and considering the age of the burials composing the clusters as well as their geographic location, the identified pattern cannot be interpreted as the result of changes in grave good preference over time. Also, it cannot be attributed solely to raw material availability. Fox canines and Dentalium sp. shells were readily available in southern Europe during the Gravettian; stone blades and a variety of bone awls were manufactured at Gravettian sites in northern Europe. Yet they were not used as grave goods in these regions. The ubiquitous presence of artefacts made of mammoth ivory in the eastern European burials does not explain the divide between the two main clusters. Pendants made of ivory, but of a different morphology, are also found in two burials from Italy, included by multivariate analyses in the Italian cluster. A third alternative hypothesis proposes that objects associated with Gravettian primary burials, and personal ornaments in particular, were simply offerings manufactured to be placed in the grave and were not objects worn by the deceased during their lifetime; that is, they would not reflect Gravettian vestimentary practices. However, microscopic analysis of grave goods associated with these burials (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren, Zilhão and Trinkaus2003c; White Reference White and Camps-Fabrer1999; additional data are unpublished) reveals that personal ornaments bear intense use-wear traces. This is particularly striking in the case of the Lagar Velho child, associated with four red deer canines from four different hinds and stags with one bearing evidence of having been recycled before being incorporated into the child’s beadwork. This indicates that the ornaments found in Gravettian burials were used as ornaments by the deceased during their life and played a role in expressing their vestimentary codes.

An additional alternative hypothesis would be that only certain members of Gravettian societies were inhumed and that, as a consequence, associated artefacts would indicate their social status rather than cultural affiliation. One may reasonably expect in this case (see previous discussion) that some divide would exist between personal ornaments used by members of ‘privileged’ social groups and those used by the other members of the community, and that such difference could be identified when contrasting personal ornaments associated with burials with those lost or disposed of at habitation sites. Although a comprehensive database of Gravettian personal ornaments is still under construction, available data and our own results appear to contradict the grave goods–social status equation. Personal ornaments associated with the Lagar Velho and Paglicci burials are similar to those found at contemporary Portuguese habitation sites and in the habitation layers of Paglicci cave (Vanhaeren & d’Errico Reference Vanhaeren, Zilhão and Trinkaus2003c; additional observations are unpublished). Also, if the exclusive function of Gravettian personal ornaments was to convey the social status of the deceased, grave goods associated with burials would not, once submitted to multivariate analysis, cluster geographically but rather would associate individuals belonging to those classes independently of the location of the burial. This suggests that even if conveying social role was among the functions of personal ornaments, they also unknowingly reflected cultural affiliation within the Gravettian technocomplex.

In other words, even if they were partially true, the last two hypotheses (offering and social status) would not be, in the light of our results, in contradiction with our contention. Differences between regions in the offerings placed in the graves or in the personal ornaments used by a particular social group would still be better explained as reflecting cultural geography. In the first case cultural differences between regions would be expressed by differences in mortuary practices rather than vestimentary codes, in the second by the compliance of a given social group rather than the entire society to principles governing the way it should dress. We must therefore conclude that grave good variability is a proxy for the cultural geography of Gravettian populations and probably reflects ethno-linguistic diversity, an argument based on the variability in bead type associations recovered from Aurignacian contexts.

This conclusion raises the question, which will need to be addressed in the future with appropriate methods, of whether the identified pattern is a function of distance between groups, and the result of horizontal transmissions through long-term trade and exchange systems (Jordan & Shennan Reference Jordan and Shennan2003; Moore Reference Moore and Terrell2001; Terrell et al. Reference Terrell, Kelly and Rainbird2001), or whether it reflects firm, though fluctuating, cultural boundaries determined by historical processes leading to group fission and isolation (Kirch & Green Reference Kirch and Green1987; Renfrew Reference Renfrew1987; Gray & Jordan Reference Gray and Jordan2000; Tehrani & Collard Reference Tehrani and Collard2002, Reference Tehrani2009; Rigaud et al. Reference Rigaud, Vanhaeren, Queffelec, Le Bourdon and d’Errico2014).

The type of analysis conducted here on Gravettian grave goods is still missing for burials dated to the end of the UP. The contextual analysis of grave goods from Magdalenian burials suggests that some of them reflect more the social status of the deceased than his or her ethnic affiliation and point to societies that were characterised by some degree of social stratification, if not enduring ranking systems. Changes in grave goods between the Gravettian and the Magdalenian may signal a shift in social complexity that needs to be studied through the analysis of personal ornaments lost or disposed of at habitation sites across the entire European territory. The implications of such complexity for UP ideologies and the way they conceive the afterlife still need to be explored through a detailed contextual analysis of grave goods. In particular, novel information could result from the identification of ‘offerings’ as opposed to objects used by the deceased during his or her lifetime. The latter represents for the moment, in our experience, the more common type of grave good associated with UP burial.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors of this book for inviting us to attend the Death Shall Have No Dominion symposium and to contribute a chapter to this volume. We also thank William Banks for a critical reading of the manuscript and acknowledge financial support from the European Research Council (FP7/2007/2013, TRACSYMBOLS 249587). Figure 4.2a, b, and d copyright Libor Balák, Antropark, reproduced by kind permission; Figure 4.2e and f courtesy of João Zilhão; Figure 4.2h courtesy of Maria-Grazia Ronchitelli.