Overlapping Views

J.K. Rowling describes depression as “[t]he absence of hope. That very deadened feeling, which is so very different from feeling sad” (Bennett, Reference Bennett2013). She embodied that description in the characters of the Dementors in her Harry Potter novels. Winston Churchill is said to have described it as his “black dog”. When examining the phenomenology of depression, one soon realises that depression is experienced in different ways by different people. We also know that individuals may have more than one, sometimes even contradictory, set of views of depression. Yet what is less known is why individuals come to espouse a particular view, or set of views, of depression.

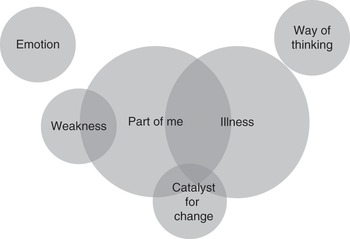

Most of the women I spoke with expressed more than one view of depression. This finding contrasts with the emphasis that some biographical and narrative researchers have placed on narrative coherence – particularly thematic coherence – of self-narrative (McAdams, Reference McAdams2006). Yet as several such as Rogge (Reference Rogge, Pilgrim, Rogers and Pescosolido2011) note, individuals vary in the extent to which they are consistent in the narrative they use, and specifically the extent to which they view their diagnosis as biographically disruptive (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Ong and Sim2006). This chapter will explore these differences within individual narratives in more detail. In particular, possible reasons for the frequent blending of views of depression among the women I interviewed are discussed towards the end of the chapter where the most commonly used combinations – that of “depression as an illness” and “depression as a part of the self” – are examined in more detail.

The Venn diagram in Figure 2.1 represents how the views of depression are interrelated. It shows which views overlapped with each other, and (roughly) the extent of overlap. For example, the degree of overlap between “part of the self” and “illness” circles reflects the number of interviewees who viewed depression as a part of their self as well as an illness. Some even viewed depression in three ways – a part of the self, an illness as well as a catalyst for change.

Figure 2.1 Overlaps in views of depression

It is possible that women tend to use more than one way of describing depression because one view of depression is the individual’s preferred view whereas the second (or third) is invoked either for convenience or ease of reference. Alternatively, individuals may change their view over time, and their expression of these different views during their interview may be a testament to both their old and current views. One interpretation of the most common combination of “illness” and “part of the self” is that depression is seen as an illness which resides in the self and, owing to the extent of its influence on and duration in the individual’s life, is inseparable from it. Yet another interpretation of this combination of views is that depression is seen primarily as an illness, but one which has a significant impact on the self. Finally, an illness versus part of the self viewpoint sees the two views at odds with each other and is often seen in the context of the interviewee trying to decide where to assign responsibility for certain behaviours. The last section here explores why and how interviewees combine the two views or pit them against each other.

Depression as an Illness

There is a range of reasons for why women describe depression as an illness. Some of those I spoke with stated that their view of depression as an illness was probably influenced by their clinician, others they had spoken to or the literature they had read. A few women said they described depression as an illness because depression made life harder for them; a few said it made them depart from what they considered to be their normal mode of function; and a few others saw it as an illness because (or when) it affects one’s physical health. Some described depression as an illness because for them it shares the quality of feeling out of their control as other illnesses do.1

Most of the interviewees who described depression as an illness were diagnosed with bipolar depression and stated that they had a family history of depression. In contrast, the majority of those who described depression as a part of their self were diagnosed with unipolar depression and only half said they had a family history of depression. This relationship may be the result of a number of factors. First, as the chapter on diagnosis (Chapter 3) discusses, the public tends to view bipolar depression as “more serious” or “more biomedical” than unipolar depression, and those I interviewed expressed similar views. Second, if a particular trait is believed to be inherited, it can take on a deterministic element and come to be seen as inevitable. Thus, if an individual believes her depression to be inherited, this may well cause her to view depression differently. This trend within those who described depression as an illness, in contrast with those who described it as a part of their self, may thus be a reflection of how difficult it is to disentangle an individual’s beliefs about her diagnosis, knowledge of her family history and views of her condition.

Some interviewees said they preferred viewing mental illness as akin to physical illnesses because they felt that this view avoids the shame associated with the former:

Heather: At the time, I felt like depression made me a failure, but having come out of the other side now I see it as you get ill, you go to the doctor, you get better. Why should it be any different for having a mental illness as opposed to a physical illness? So I’m not ashamed of it anymore.

Women such as Heather self-reflexively stated that describing depression as an illness is a way of giving it the same status as physical illnesses. In their view, this legitimises depression such that it makes as much sense to blame the sufferer of depression for her condition as it is to blame a sufferer of influenza. As a strategic move, as well as one often encouraged by the medical profession, the illness view is supposed to establish depression as a condition which is reified beyond the self, separate from “normal” sadness and worthy of medical attention (Helman, Reference Helman, Lock and Gordon1988; Lester & Gask, Reference Lester, Gask, Gask, Lester, Kendrick and Peveler2009). This view removes any reason for shame, because as an illness, depression is represented as “beyond rational mastery”, with its representation “relegated to the realm of the body over which we have no conscious control” (Kokanovic et al., Reference Kokanovic, Dowrick, Butler, Herrman and Gunn2008: 464). The prevalence of this view among the women interviewed, and its instant association with the sick role and all that goes with it, demonstrates the power of the biomedical narrative within the illness view. As Estroff describes, “[t]he clear association of medical/clinical models with self-labelling also suggests that the mantle of medicalisation or the ‘no-fault’ provisions of having an illness (Parsons, Reference Parsons and Jaco1972) are embraced by many” (Estroff et al., Reference Estroff, Lachicotte, Illingworth and Johnston1991: 361–362).

This perception of course ignores the fact that the individual to some extent can still control many illnesses. The risk of acquiring lung cancer, for instance, can be greatly reduced by not smoking. The risk of acquiring heart disease can be minimised by maintaining a healthy diet and lifestyle and so on. The illness view avoids seeing depression as a judgement of character or an indication of moral failure. It thus appears to succeed in separating depression from the moral self but, as described later, in practice does not succeed in dissociating depression from the self completely. Moreover, as discussed in Chapter 4, the relief of some responsibility afforded by the simple illness view is a double-edged sword, for a reduction of responsibility also means a reduction of control.

The term “illness” as it was used in the interviews was a flexible one, and was adopted for a variety of reasons. A number of researchers have found that individuals diagnosed with depression find it helpful to view it as a biomedical illness (as Zoe says below), but that commitment to this view is stronger during the initial stages of depression and is more likely to be combined or replaced by another view later (Badger & Nolan, Reference Badger and Nolan2006; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Datto, Ruckdeschel, Knott, Zubritsky, Oslin, Nyshadham, Vanguri and Barg2006; Holt, Reference Holt2007; Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Hansen, Traulsen and Eskildsen2002). Alternatively, individuals can simply be conflicted in their views. Most of those I interviewed indeed viewed depression in more than one way. As I probed their reasons for adopting the illness view, I began to see the nuances behind this depiction of depression.

Zoe is one of the interviewees who views depression as an illness because she feels it shares that “out of control” quality with physical illnesses. At the same time, Zoe implies that depression is unlike other illnesses because it straddles both the biological and the psychosocial sphere in its likely causes, symptoms and treatment more than other illnesses:

So why wouldn’t you expect to have control over [your depression]?

As an illness, I suppose it’s just easier to think about because you can’t really blame anything but it just makes the most sense to think of it like that. Yeah and then there’s not much control you have over lots of illnesses. But like other illnesses, there’s things you can do to help. But it is difficult because it’s at the interface between biology and social interactions and how it works.

That’s an interesting point. So it helps to see it as an illness. Do you think that’s an accurate way of seeing it?

I mean, but that’s not to say that I don’t think I have any responsibility to help myself, if you see what I mean. It’s not just saying it’s an illness and there’s nothing I can do about it. So I think because it’s at the interface, it’s an illness that you can also tackle with psychological techniques. But then it’s still an illness, it’s just that it can be tackled with thoughts as well.

Whereas women such as Zoe relied on a flexible definition of illness which includes both mental and physical symptoms, a few women supported their view that depression is an illness because it has physical as well as mental effects. This justification implies that unless a condition has physical symptoms, it is not really an illness. Wendy provides an example of this view as she makes a sharp demarcation between the mental and the physical in her definition of when depression becomes an illness:

Have you ever heard people describe [depression] as an illness? And what do you think about that?

[…] I think the physical aspects that can be cured, like not being able to walk or hold a pen and write, that is an illness and it can be cured by drugs or whatever. Talking in that case wouldn’t exactly help, but the way of thinking and the different way of thinking – that’s not an illness. That just is.

So are the physical things an illness because they are physical?

I’d say actually yes I’d say so, because you really can’t … I mean not being able to walk when there’s nothing wrong with your legs, that’s not normal. Whereas for me, thinking in a particular way, that is normal for me, whereas not being able to walk is not normal for me.

Wendy also touches on another justification used by a few other women for the illness model of depression, which is that it departs from their normal mode of function. This view is similar to the definition of disease as whatever departs from “normal species functioning” (as described by Christopher Boorse (Reference Boorse1977)).2 Ingrid provides an example of this view:

You know normal people don’t sleep in bed all day. They go to work. I want a job. I don’t want to be in bed all day. I don’t want to be sitting at home. I want to be out there like everybody else. That’s how I see it as an illness.

Wendy and Ingrid are among those who make such a distinction between illness and non-illness, and it is one that appears analogous to the distinction made by medical sociologists between “disease” and “illness” – disease being the medical pathology/objective state of the body (i.e. something we can measure) and illness being the subjective experience of disorder (physical, psychological and social). Fredrik Svenaeus summarises it thus:

[t]he line of demarcation between normal being-in-the-world and abnormal being-in-the-world certainly cannot be determined with the precision of the sphygmomanometer (with which one measures blood pressure) or the sensitivity of a tissue biopsy (with which one can detect the presence of cancer). This fact should come as no surprise, however, given the nature of phenomenological investigations, and the characteristics of mental illness in general. Recall the DSM-IV criteria for a depressive episode quoted above: the episode should cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” This is a life-world matter, dependent not only upon how things “really are,” but also upon how the person and people around him (including family, friends, and the doctor) interpret them to be. In the domain of illness, in contrast to the scientifically more objective domain of disease, the question of normality is in the end always anchored in normative judgments.

While Wendy and Ingrid use the term “illness” instead of “disease”, what that term refers to, for them, is a state which deviates from what is normal for the species (on Ingrid’s definition) or what is normal for the individual (on Wendy’s definition). In either case, they seek to anchor depression within “the scientifically more objective domain of disease” as distinct from the more subjective “life-world matter”. Of course, the problem with such a distinction is that while sphygmomanometers and biopsies may take accurate measurements, the point at which a result is deemed to be problematic, and therefore classified as disease, still involves a normative judgement and is not always clear-cut. The difference may be that for certain conditions, such as a broken bone, there is much more agreement as to what the problem is and how it should be fixed than is the case for other conditions, such as mental illness (Hughes & Ramplin, Reference Hughes, Ramplin and Cowley2012). In other words, there are values inherent in all diagnoses, but there is more agreement concerning the values inherent in some diagnoses compared with others. Moreover, something may deviate from “normal species functioning” but not necessarily be problematic. Regardless of the ease with which we can separate fact from value, or disease from illness, it is noteworthy that some of the women draw on such a distinction in order to separate depression from their self.

An alternative interpretation of the illness view is that it functions as a mechanism to separate, and in doing so protects, the individual’s core self from her malfunctioning body (Czuchta & Johnson, Reference Czuchta and Johnson1998; Register, Reference Register1987). An anonymous mental health service user, for example, writes that recognising that he had an illness enabled him to then look to the part of his self which he considered separate from the illness in order to regain hope of moving on (Anonymous, 1989). Deegan also writes that “the most important vocation for persons struggling with mental illness is the work of becoming one’s self in spite of one’s illness” (Deegan, Reference Deegan1989: 143) (emphasis added). Yet individuals espouse diverse definitions of “depression as illness” and, as described later, do not necessarily believe that the “illness” and the “self” are mutually exclusive. It is a finding which also problematises any attempt to apply the notion of “biographical disruption” to such cases. As Fox (Reference Fox1993: 146) observes, the focus on biographical disruption “serves to ‘fabricate’ a subject who is effectively ‘trapped’ within her/his ‘pained’ body and is required to ‘adjust’ or ‘adapt’ to the limitation this engenders”. For those who were able to separate the “illness” from the “self”, it could indeed be said that the self was experienced as having to adjust to the disruption wrought by the “illness”. However, most of those interviewed did not consistently hold to this concept. Hence, it is difficult to say whether, and to what extent, the individual’s biography had been disrupted.

Depression as a Part of the Self

About a third of those I interviewed viewed depression primarily as a part of who they are.3 Of these, half felt that depression had gradually developed at the same time that their character was forming, rendering it difficult to distinguish whether depression had caused certain mental, emotional and behavioural tendencies to develop, or whether the direction of influence went the other way. Yet what they felt was almost certain was that it was now difficult to extricate depression from their self – whether it was seen as an established character trait which flared up now and then, or an “old friend” or partner who feels like part of them simply because it has been with them for so long, or a warning sign that not all is well with their life and something had to change.

Some women felt that depression is a part of who they are due to the length of time they had experienced it or the number of times it had recurred. A couple of the interviewees were similar to those in David Karp’s book Speaking of Sadness in that at first they did not think what they had was an illness, but rather a personal failing. Yet when their low mood persisted after they felt the reasons for it had disappeared, they came to the conclusion that it must be an illness related to a lack of serotonin. Karp and most of those he interviewed came to the conclusion that because any external reasons for depression had disappeared, the cause must be biological (Karp, Reference Karp1996). Among those I interviewed, however, there were also individuals who had the opposite view – that because external reasons had disappeared, the cause might lie within the self. This finding became apparent during interview analysis, and the sample size for each view was too small to be able to speculate as to why some saw the persistence of depression despite the absence of external reasons as an indication of a biochemical problem at its root rather than a sign that they needed to reassess themselves or their lives.

I will, however, present Barbara’s story as she was one of the few women whose recurrent experiences of depression caused her to rethink its possible causes. Rather than thinking of depression as something transient, she began to consider whether the recurrence of depressive thoughts was a reflection of some deep-seated belief.

So has your impression of [depression] changed over the years?

Yeah I guess […] I saw it as really I guess like a medical thing. I guess like “Oh it’s just a chemical imbalance in the brain and sometimes I feel depressed so I shouldn’t worry about it.” I think that just meant that I didn’t really deal with any of the issues that were making me feel bad.

So how did that change?

And that changed more when I started to get more depressed and then I couldn’t really work out … because it went on for longer and it was worse … I wasn’t really able to say to myself, “Oh this is just something that happens sometimes and it’ll go away”, because I started to see, “Well actually these are the things that I really think. Maybe I really think these things.” So maybe which part of it is really me? (emphasis added)

Here, Barbara expresses how the internal conflict between viewing depression as a chemical imbalance versus viewing it as part of the self can manifest itself. For women such as Barbara, a realisation that something more serious was wrong caused them to look inward to examine the cause. As Barbara indicates, this inward search was a process of self-discovery. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the women who viewed depression as a catalyst for change also fell into this category. Insight achieved through counselling or other means often made them conclude that at the root of their depression was a mistaken or ill-founded belief about themselves or the world, as Barbara again illustrates:

The main thing that helped me improve I would say was counselling and feminism […] It was really helpful talking about some of the things and the hang-ups that I’d had that I’d never really talked about. And it was weird because it wasn’t like I hadn’t talked about them because I’d actively not wanted to talk about them, it was just because I hadn’t consciously thought about them enough.

And loads of stuff from my course – like I was doing an anthropology class on colonialism and learning loads about how social stereotyping works and different social pressures and loads of analyses about different power relations. It just made me realise that all the things I’d been feeling, I’d been blaming it all on myself but actually I’d been insecure, but all of the things that have been coming out has been the result of me picking up social stereotypes as well and feeling like I had to be this way.

Of those who viewed depression as a part of who they are, it is telling that only two viewed it solely as such. That is, the vast majority of those who primarily viewed depression as a part of their self also incorporated views such as the illness model, or the catalyst for change model, into various aspects of the way they view depression.

Depression as a Catalyst for Change

Just over a quarter of the women I interviewed said they felt that depression prompted them to gain insight and to change aspects of themselves or their lives. However, only a few women focused on this aspect as their primary view of depression. These women saw the changes they made as a result of having had depression as more than just minor additions to their lives. Instigating change, they believed, was depression’s primary function. Predictably, this is why all the women who viewed depression as a catalyst for change said they would not choose to permanently remove depression from their lives. To them, it is their mind or their body’s way of telling them that something is wrong and needs to change, or forces them to come to terms with aspects of themselves or their past. Gail describes this idea here:

Do you think, if you could press a button, theoretically, that would ensure that you would get rid of depression forever, would you press it?

No, because that’s the best way to know how you kind of get away from your true self again. If you don’t get any signs on the way, then you can really go a long way from who you’re supposed to be, and then maybe you realise when it’s too late. So I would not do it, no.

This idea is mirrored in the literature by authors such as Siegel (Reference Siegel1990) who hypothesise that individuals become ill because they “need” their illness, or who attribute their achievements and personality changes to their illness (Butler & Rosenblum, Reference Butler and Rosenblum1991; Higgins, Reference Higgins1992). Alternatively, Hydén (Reference Hydén1995) would describe such a psychological change as a switch from being merely a character in one’s own life to becoming the author.

Williams might describe this group as having lost their “personal telos and sense of identity” through their depression experience, as he describes a case of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis who “saw her illness as the bodily expression of a suppression of herself” and “the stress of events and the suppression of herself as merely components in the social process of being a wife and a mother” (Williams, Reference Williams, Hinchman and Hinchman1997: 199). Yet a loss of identity only describes half the story for women such as Gail, because having recognised that they had lost “who you’re supposed to be”, they described that this recognition then catalysed them into changing course or “regaining their self”. Gail’s view is instead akin to what Frank (Reference Frank1991) describes as a “dangerous opportunity”, whereby the destruction of the self caused by depression provides an opportunity to create a more authentic self. The catalyst for change view can also be understood in terms of Radley and Green’s (Reference Radley and Green1985, Reference Radley and Green1987) concept of secondary gain, which Herzlich (Reference Herzlich and Graham1973) refers to as “illness as liberator”. Although in reference to the liberation from the usual burdens of work afforded by an illness, and the alternative avenues of fulfilment which can result, the phrase is nevertheless apt here. Other authors would portray this transformation as a new meaning to life and a change in values which emerges from the struggle to make sense of the illness experience (Cobb & Hamera, Reference Cobb and Hamera1986; Hall, Reference Hall1990; McLean, Reference McLean1991).

A variation on this way of thinking but which I still consider part of the “catalyst for change” viewpoint is the view that it is not depression as such but the difficult life experiences that individuals had which acted as catalysts for their character development. According to this type of “catalyst for change” view, reflecting on and recovering from their hardship caused them to learn, grow and strengthen their personality. An extract from Anne’s interview is provided here to illustrate this view:

So do you think it’s a part of your character, or just a passing thing, or an illness or … ?

What? Which aspect?

Depression.

Hmmm. That’s a good question. No I don’t think it’s a part of my character. It’s a passing thing. It’s because of the circumstances mostly […]

Ah that’s very interesting. So do you think depression has changed you as a person?

As there are some like Anne who differentiate between the experience of depression and the difficult circumstances which they believe prompted their depression, this differentiation adds a nuance to the “catalyst for change” view of depression, and one which has not appeared in accounts of depression so far. The difference may appear slight, but it is meaningful, because what Anne is saying is that she feels more resilient now, such that she would probably not dip into depression in response to a stressful period in the first place. Whereas for Gail, a depressive mood serves as an indicator for her that something in her life must change.

Those who described their depression primarily as a catalyst for change were diagnosed with unipolar depression and felt they tended to experience something in their lives that triggered their depression. They were also much more hopeful and optimistic about their future than any other group. Some of the women outside this group who did not experience a trigger felt guilty because, in their eyes, not experiencing a trigger meant that they had no right to be depressed, or that experiencing one would have at least made it easier to explain and justify their depression to others. In a similar sense, a trigger provides for a narrative that weaves into the individual’s life. Their depressions are easier to understand, and hence easier to relate to, than those whose depressions arise seemingly out of nowhere. But when depression causes the individual to discover something about herself, to learn something new, to rethink her past or her future, her goals and values or the way she lives her life, then it goes beyond simply providing her with a neater narrative – it begins to serve a purpose. There is then even more cause for optimism because not only did the individual learn from and overcome depression in the past but if it happens again then, according to this view, it would probably happen for a reason.

For women who view depression as a catalyst for change, depression ceases to be something to fear and instead becomes an indicator that something in their lives or their selves must be changed. This point of view can only come with insight. Those who gained insight into themselves or their lives as a result of depression were not confined to the “catalyst for change” group, but very few of this group described depression as an illness overall. On the other hand, at least a third of those who viewed depression as a part of their self indicated that they gained some insight or learnt something valuable about themselves from having had depression. Having said this, depression was by no means seen as an easy lesson or a welcome event. The insights that depression, or the hardships surrounding it, gave were painfully won. Kleinman summarises this notion in his description of lessons learnt from chronic illness: “[f]or the seriously ill, insight can be the result of an often grim, though occasionally luminous, lived wisdom of the body in pain and the mind troubled” (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1988a: 55).

Depression as a Way of Thinking

Of all those I interviewed, only one woman described her depression as a way of thinking. This woman was Wendy. Raised in a rural setting, Wendy felt isolated and restricted until she grew old enough to move away. At school, there were few students with whom she could relate and she found it a lonely experience. Despite these contributing factors, Wendy felt her depression was something inbuilt – that although those social factors contributed to her depression, she suspected she might have been depressed regardless of her social situation.4 When I asked at what age she believed her depression began, she stated that her thinking and behaviour had been what most people would probably consider to be depressed since at least the age of seven. She explained that she came to this conclusion by contrasting the way she used to think and behave before and after she began taking antidepressants. The change, she explained, was so great that she stopped taking them after just a few months.

So why did you take yourself off that [medication]?

[…] It completely alters the way you think and behave and everything and that’s so disturbing.

So what kind of things for example?

[…] The way you think about the world. The way you perceive … I don’t know because it’s just ways of thinking. Basically the way I thought was normal was basically depression. And okay by that stage it was bad enough for me to notice that I couldn’t function, so I had to go on medication because that’s the only way to fix it, but I can’t remember but I knew that I was completely different to what I was used to. I suppose it’s like being on any mind-altering drugs. You think different thoughts and perceive things differently.

The change was akin to what Kramer (Reference Kramer1993) describes in Listening to Prozac as a complete personality change. But unlike Kramer’s patients, Wendy was not happy with this new personality because it was so alien to her. To Wendy, depression is a paradigm which is part of her sense of self – her unique way of seeing the world. She does not accept society’s conventions – its “Western corporate material culture” – and does not relate to the mainstream with its emphasis on appearance, money, marriage and having children. At university, she was finally able to find others who related to her attitude. Until then, she had felt alone in her unease with society’s values.

However, it was not until her late teens that a very low mood began to accompany this frame of mind and eventually had an impact on her body. She had thoughts of committing suicide and could no longer walk properly or even pick up a pen. Realising that something was very wrong, she went to a doctor and was prescribed antidepressants. Wendy explained that the antidepressant restored her mood and physical function, but also altered her thinking. It was its effect on her thinking which she found to be an especially unsettling experience. Yet despite the elevation in her mood and physical function, she was not tempted to stay on the antidepressants because of how strange and artificial they made her feel. In this respect, she was resisting society’s bias against dysthymic individuals – a bias which can push such individuals to take medication they might otherwise prefer not to take (Weisberger, Reference Weisberger1995). She describes her experience on antidepressants as “like being on a constant high” or on “mind-altering drugs”.

Unlike many others I interviewed, Wendy does not use medication to help her define what constitutes the “illness” and what does not. Doing so would mean that everything which was altered by the medication, including her way of thinking, was part of the illness. To Wendy, it felt as though everything had been changed by the medication. Accepting a definition of illness as everything that was altered by medication would thus entail a loss of self to the illness. Instead, she chooses the definition of illness to be whatever deviates from her normal state of functioning. So the physical and mental changes which occurred during the worst stages of her depression are what she considers “illness”. On the other hand, she does not consider her attitude, which others might consider to be a depressive outlook, to be part of the illness because it is her normal mode of thinking.

Wendy thus incorporates two different descriptions of depression into her viewpoint. At its worst stage, depression, to her, becomes an illness worthy of treatment with antidepressants. In its milder form, it is a way of thinking which is part of her self and of which she has no desire to be rid. She still calls the latter “depression” because it was also transformed by the antidepressants and because she understands that society would consider her way of thinking to be a form of depression. However, she describes it as an attitude or way of thinking which could be seen as a subset of the “part of self” view which nevertheless has some unique characteristics. In contrast with other accounts of the self in chronic illness (e.g. Davidson & Strauss, Reference Davidson and Strauss1992), Wendy’s sense of self was not threatened by depression because she believes it has always been part of her self, hence there is nothing to “rediscover” or “reconstruct”. Instead, Wendy’s case could be seen as supporting Jensen and Allen’s notion that “individuals could conceivably experience disease as wellness by accepting disease as an integral part of themselves” (Reference Jensen and Allen1994: 361).

Several women who felt that the condition is now a part of their self were not proud to say so. Their tone was mostly one of conceding that having experienced depression as a part of their life for so long, or lacking any other satisfactory explanation for its occurrence, they feel inclined to admit that it must be a part of their self. Like it or not, they simply cannot imagine who they would be without it. Wendy, on the other hand, is proud and defiant. Simply deviating from what is considered a normal attitude by the rest of society does not make her ill. Illness, to her, is what deviates from her normal mode of function.

Christopher Dowrick (Reference Dowrick2009: 101) argues that “the major driver behind the concept of depression as a medical diagnosis is a more fundamental set of cultural perceptions in Western societies, where our expectation that happiness is the natural way of being leads us to see negative emotional states as intrinsically deviant from normality”. The difference between Wendy and Ingrid’s accounts reinforces this point, as Ingrid accepts the societal expectation that happiness is a natural way of being, whereas Wendy rejects it. To return to Jensen and Allen’s point, Wendy thus defines what society calls “disease” as “wellness” (or rather, “illness” and “wellness”) as far as her personal biography is concerned, and simultaneously challenges the belief that what is called depression should be “negatively evaluated” (Dowrick, Reference Dowrick2009: 121). Bill Fulford asserts that “we are concerned, typically, with desires, beliefs, emotions, motivations, and so forth, areas of experience and behaviour in which human values are, characteristically and legitimately, diverse” (Reference Fulford2001: 82). Perhaps, given Wendy’s case, we should take this assertion more seriously.

Depression as a Weakness

Views of depression overlap with each other, and the view described here is no exception. At least two women described depression as a weakness or a tendency alongside another description of depression. For Evelyn and Frances, depression is a set of weaknesses or sensitivities which, if ignited, can set off a depressive episode. Frances illustrates this view here.

But do you yourself see it as an illness or something else?

I feel like you have weaknesses and tendencies that build up over a long period of time […] I’ve had a reasonable upbringing and so on, but I mean terrible losses and painful horrible things have happened to me around my sense of self I suppose and my safety and my self esteem and all that kind of thing. I think you get weaknesses and it’s like fault lines in a volcanic area or an earthquake area. And then there’s a trigger. Now I don’t consider that that is an illness, but that is a weakness. Maybe it’s a bit like having a heart condition where you take this medication and be a bit careful, you know, but you’re not ill, you know? So I don’t know. It’s hard isn’t it?

The weakness view, however, is quite fraught. It is quite close to describing depression as a weakness of character, leaving individuals open to having their struggles dismissed as simply needing to “buck up”.5 Yet this was not what Frances and Evelyn were saying. Describing depression as a vulnerability that can be triggered did not in any way diminish its seriousness. Rather, it appeared to be a way of normalising depression while still recognising their distress, in much the same way that the teenagers of Mervi Issakainen’s (Reference Issakainen2014) study sought to escape the views of depression as a mental illness and the view of depression as “a matter of pulling oneself together” by framing it instead as “a normal but serious affliction”. Such a move can be quite strategic when considering the fact that the biomedical model of depression actually contributes to, rather than alleviates, stigmatisation (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Holzinger, Carta and Schomerus2011; Lafrance, Reference Lafrance2007). Richard Bentall explains that this is because the biomedical model promotes a view “that humans belong to two sub-species: the mentally well and the mentally ill” (Bentall, Reference Bentall2016).

It may be tempting to characterise the “depression as a weakness” view as an offshoot of “depression as a part of me”, but Frances was resistant to this idea:

Did you ever have any of your therapists or doctor describe it to you as an illness or sort of in terms of chemical imbalances? And what do you think of that?

Well they do I suppose call it a chemical … Well [doctors] call [bipolar disorder] a personality disorder don’t they actually? Which really scares me. I mean I don’t accept that. I had a great personality thank you and still do and I’m not a danger. I mean I really object to that.

Thus, distinguishing the “weakness” view from the “part of self” view allows for more detail and a more accurate reflection of the individual’s representation of depression within her narrative. The perception of having an underlying weakness that is triggered by a circumstance or event was common to both Frances and Evelyn and occupied a crucial role in their narratives, just as triggers for depression played a crucial role for those who espoused the “catalyst for change” view. However, in the “catalyst for change” view, understanding a trigger for depression offers insight, whereas in the “weakness” view a trigger offers no such insight.

Depression as an Emotion

One of the women I interviewed did not describe depression in any of the ways mentioned so far. She held steadfast to the belief that depression is an emotion, pure and simple. For Penny, depression is not a disease that one can get rid of simply by swallowing a pill. In contrast to the “illness” view, Penny emphasises individual responsibility and describes depression as an emotion which the individual can control and think oneself out of by thinking positively. Penny’s description of depression as “just something that you feel” makes it sound deceptively mild. Yet given her story, depression was anything but mild. She firmly believes the main cause of her depression was her parents’ violent rows, their divorce and the resulting instability. This view is interesting because at the age of three she was deemed hyperactive and placed on Ritalin, which she says did not work but made her depressed. As a result, she was taken off Ritalin and placed on antidepressants. She then took antidepressants from the age of 6 until 13, culminating in a suicide attempt, until she and her mother decided she should stop taking antidepressants. It is interesting that although she believes Ritalin played a role in causing her depression and that the antidepressants did not only fail to help but actually made her worse, she does not blame the medication for causing her depression but sees the main cause as having been in an unstable family environment.

This view is consistent with her story that although coming off the antidepressants helped, her family life was still unstable and she was still withdrawn as a teenager, going through weight gain and six months of bulimia. Consequently, her depression improved a great deal more when she left home. The resulting stability and independence she gained, as well as meeting the man who became her husband and the continuing support from her mother, provided her with more strength and influence to be able to “view things positively” (in her words). Since leaving home, she has been able to reflect on past events. She puts her improvement down to working through her feelings about her parents’ separation, taking up yoga, support from her husband, resisting antidepressants and, in her words, “relying on herself”. Combining support with self-reliance seems to have empowered her to the point where she can control how she feels about events that take place in her life fairly well.

Penny’s view of depression is similar to “depression as a catalyst for change” in its emphasis on depression as something which is not a disease but a life problem that can only truly be solved by insight. In fact, Penny shares many characteristics with the majority of those who described depression as a catalyst for change: she believes her depression was triggered by circumstances in her life, that it was caused by environmental or life stress rather than biology, is not comfortable with taking medication for depression, feels she has a fair degree of control over her mood, believes that her depression is a temporary rather than a chronic condition and was diagnosed with unipolar (not bipolar) depression. Like the “way of thinking” and “weakness” views, the representation of depression as “an emotion” is quite a rare one. On the face of it, the rarity of this view may seem counter-intuitive given the very emotional form that depression can take in many individuals. Yet this rarity may be a result of what Abram de Swaan (Reference de Swaan1990) describes as “protoprofessionalisation”, in which the lay person accepts and, to some extent, internalises the professional accounts. As Michael Power and Tim Dalgeish (Reference Power and Dalgleish1996) note, psychiatric texts devote a great deal of attention to “affective disorders”, yet hardly any to the nature of emotions. Even when emotions are discussed in such texts, the discussion usually occurs in a separate sphere from discussions on psychopathology (Pilgrim & Bentall, Reference Pilgrim and Bentall1999). Nevertheless, Penny’s “depression as an emotion” view provides support for Simon Williams’ proposition that it might be

better to think in terms of emotional health (as a fully embodied phenomenon), than a sociology of “mental” health. Appeals to emotional health, echoing the above points, help to: (i) avoid the medico-centric and/or dualist ring of mental health; (ii) put embodiment centre-stage; and (iii) bring emotions to the fore in all discussions of health, including the “afflictions” of inequality. (Williams, Reference Williams2003: 151–152)

Combinations of Views

Despite encouragement by the medical establishment to view depression as an illness that is separate from the self, many people tend to question this distinction. Most of the women I interviewed who at some point in the conversation spoke of depression as an illness also described it as a part of their self, and vice versa. Perhaps, then, there is some truth to Horacio Fabrega and Peter Manning’s (Reference Fabrega, Manning, Scott and Douglas1972) assertion that what separates mental illness from other illnesses is the impossibility of separating the self from the condition. There were different senses in which depression was invoked both as a part of the self and as an illness. Roughly half of the interviewees said they had difficulty categorising certain traits or quirks as an illness because the traits or quirks felt too much like a part of their personality. Imogen was one such person:

But the most frightening thing I read recently was about a sort of chapter in this book about manic depressive illness and it was about personality and interpersonal relationships. And I read it and I just thought, you know, you think of yourself as an original person, and I read it and just thought, “Oh my God, there’s so much of it there that’s completely how I’m like”. […] It said something about how bipolar people can be very … they sort of fall in love really easily and have these really passionate sort of affairs and really sort of love people to extremes, like to a complete extreme – almost possessiveness and quite horrible ways really. And I read it and just thought that’s probably me. Oh dear. You know, and I was kind of horrified to realise that there are these patterns of behaviour that are quite common between people with the illness […] And even now I kind of think, “Is that just me or everybody goes through things like that? Or how far is it the illness and the depression?”

Another way that the women I interviewed invoked both “depression as an illness” and “depression as a part of the self” views was simply to refer to it as an illness at times and as a part of their self at other times. Take Layla, for example:

When I was a bit younger, I would have been too scared to tell someone [that I have bipolar] because I’d think that they’d think, “That’s a bit rubbish. What are you talking about?” Whereas now I feel a bit stronger and a bit more in control to tell people that that’s what I’ve got. It’s just me. It’s part of my personality.

Later in the interview:

So do you think your idea about bipolar disorder has changed over the years?

Yeah definitely. I think I used to think people who had things like that were crazy and couldn’t lead normal lives […] But I also see it more as like a medical illness I think.

For some women, describing their condition as a part of the self at certain points during the conversation and as an illness at other points produced contradictions in their narrative, whereas for others it did not. The reasons for this discrepancy in views of depression also varied. Sometimes the interviewee resisted calling depression an illness because it sounded “like something was wrong” with her, made her feel like an invalid or because she did not buy into the biomedical causation model. At other times the individual might reconsider depression to be an illness after all by virtue of its response to medical intervention. An antidepressant is supposed to fix a chemical imbalance in the brain. Since it worked, they reasoned, a chemical imbalance must have been at least one of the problems, as Karen articulates:

Do you think biology plays a part in it?

[…] I mean, biology has a part because if biology doesn’t have a part then Seroxat shouldn’t work, and it does. And I definitely know that because … I don’t know. Either the power of placebo is so great that you go from a point where you can’t imagine your life anymore, you can’t imagine living, to a point where you’re back to normal.

Sometimes the discrepancy between viewing depression at times as an illness and at other times as a part of their self seemed to be between a conscious and subconscious viewpoint. For example, when I asked directly, the interviewee might say that to her depression is a part of her self, and yet at other times during the conversation she would refer to depression as an illness, sickness, condition or similar “medical” language. About half of those I interviewed believed a description of depression as something other than an illness to be more accurate, but it was sometimes referred to as an illness nonetheless as it may have simply been easier to refer to as such. For example:

Karen: It might. The ability to, like I said, empathise with others, to help others, may be something positive. Besides what I know about depression? No. Nobody likes to be sick.

Is it like being sick?

Karen: No, not really. It’s … When you are depressed it is because nobody can see it ….

This phenomenon could be interpreted as shifting between what Hydén (Reference Hydén1997) calls speaking in the “illness voice”, which is to describe the illness “from the inside” as someone still suffering (which in this case would be describing depression as part of the self), versus speaking in the “healthy voice” as someone whose life has been invaded by something external (which in this case would be depression as illness) or something that was in the past. I suggest two slight modifications to this perspective. One modification is that those supposedly speaking “from the inside” (although it sounds incongruent to describe those depicting depression as a part of their self to be speaking in the “illness voice”) did not necessarily see themselves as “still suffering” (or indeed “suffering” at all). Second, those who described it in the so-called “healthy voice” did not necessarily believe it was in their past. For instance, some who described depression as a part of their self felt it was probably now over, but insofar as it formed a crucial part of their past, it contributed to their current self.

An Illness that Is Part of the Self

The combinations and permutations of the different descriptions of depression I came across provide rich territory to explore. One of the permutations of the “depression as illness” and “depression as a part of the self” combination is the view that depression is an illness that is part of their self. The most common reason that interviewees gave for this view was that depression seemed entrenched either in their personality or their family history (or genetic makeup), or both. Most of those who espoused this view said their family had a history of depression and felt their depressive episodes were usually not triggered by anything. Miriam is a typical example of this combined “illness that is a part of the self” view. She grew up in a family in which most of the members have suffered from depression in one form or another. At times she described depression as an illness, but at other times described it in the following way:

I’d always felt at that stage that if I was a ball, the depression was at the centre, but it had a switch so I could switch it off. That’s what I felt. And at the end of the counselling, I was still a ball with a much smaller centre and that was fixed. And I kind of felt instinctively then that if I took that away I would be hollow. I felt like it was deeply ingrained – just part of who I am. I couldn’t take it away any more than I could take away being able to see or hear or taste. So I don’t know. I mean my brain just interpreted that as it being hard-wired in, rather than a case of nurture. […]

Why do you think it’s so much a part of you?

Miriam’s account sounds very much like biographical reinforcement (Carricaburu & Pierret, Reference Carricaburu and Pierret1995). In their study of HIV-positive haemophiliacs and gay men, Carricaburu and Pierret describe how the diagnosis of HIV for men simply reinforced aspects of their identities which had centred on haemophilia or homosexuality. For example, for men with haemophilia, it simply confirmed their lifelong illness experience. For gay men, it reinstated their personal and political struggle. In a similar fashion, the diagnosis of depression seemed to confirm Miriam’s idea of what constitutes a person, or at least what constitutes herself. However, Miriam’s is an example of a family in which nearly everyone had suffered from depression, so the other women may not have experienced biographical reinforcement to the same extent. Nevertheless, the others who described depression in a similar way expressed a sense of depression as being deeply entrenched in their personal makeup despite not knowing of any family history of depression. Instead, they felt it was something they were simply born with, just as they were born with a particular disposition. For such women, they had felt a tendency to become depressed for as long as they could remember, even if a “full-blown” depression did not manifest until much later in their lives. Often they would describe depression as an illness as well at another point in the interview. Theresa, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, provides an example of this view:

Yes in a way, but not like … I don’t know, it’s difficult. I’m still kind of … I don’t think so. I think I can’t say it’s changed me because I think it is me. It’s part of me so I can’t see it as having changed me. It’s changed thought processes and it’s changed how I see things and how I react to things and how I deal with things, but not kind of you know …

Later:

So if you could theoretically press a button that would get rid of bipolar forever, would you press it?

Oh absolutely! Straight away! Yeah of course.

Belinda, on the other hand, views bipolar depression as inseparable from her self based on the influence it has on the way she reacts to people and situations in life. Without these unique reactions, she reasons, she would not be who she is. Yet at the same time she refers to what she has as an illness.

I think I’m more than just bipolar illness but by the same token I don’t think you can separate me from bipolar disorder because so much of the way I behave and the way I interact with people and all that sort of stuff is influenced by the fact that I have much more intense reactions to things.

These three examples reflect a range of different viewpoints within those who felt that depression is simultaneously a part of their self as well as an illness. While Miriam and Belinda said that if given the choice, they would not choose to be rid of their depression, Theresa used the illness view as a justification for why she would choose to be rid of it. After all, why would anyone want to hold onto an illness? Yet it is also something she does not consider to have changed her because she believes it has always been part of her. For Theresa, depression is an illness which has always had a significant impact on her self. The two concepts are not in contradiction. Yet the inference is that if she had been born without it, she would have been a different person and, she implies, would probably have been better off.

While Miriam’s particular account of depression is a case of biographical enforcement, the “illness that is part of the self” view as a whole could be understood as a variation on biographical continuity. In Pound et al.’s (Reference Pound, Gompertz and Ebrahim1998) study of stroke in older people, illness was seen as inevitable in later life. As a result, older people, especially those from working-class backgrounds, were more accepting of hardship. In this way, stroke was almost biographically anticipated. In a slightly different manner, women who view depression as an illness that is part of the self demonstrate an element of biographical continuity insofar as depression is at least not articulated as a biographical disruption but is worked into their narrative. Their self had been developed by, and with, depression. As Theresa explained, “I can’t say it’s changed me because I think it is me.” As such, depression is experienced as a biographical continuity – if nothing else, for the inability to conceptualise what the self would have been like without depression.

Part of the Self Developed by the Illness

A few of the women I spoke to felt that depression is a part of their self that has been formed or altered by the illness. Being an intense experience, as well as a sometimes long and protracted one, these women felt that depression had left its mark on their character in one way or another, often by learned behavioural or cognitive habits. Ursula illustrates a version of this view:

It’s easier to think of [depression] as part of me, but it’s probably better to think of it as an illness […]

And which one do you think is more true?

They’re probably both true because it is an illness but it’s part of me as well because it’s a part of my experience and part of my past experience of what has formed me. So in that sense it’s part of me as well.

The experience of depressive or bipolar-related symptoms for long periods of time without being diagnosed also compounds the problem of separating personality from pathology:

Gina: I do find that difficult to distinguish between symptoms and my own character, especially because I was undiagnosed and untreated for a very long time and I feel like my personality and my character developed while I was sick …

Gina explained that even when she is not experiencing depression or hypomania, she has a tendency to behave as though she is depressed or hypomanic, implying that these tendencies belong to the illness but that force of habit has imbued her behaviour with characteristics of the illness – characteristics which were not originally her own.

Even for those who adamantly described depression as an illness, it was impossible to neglect the impact it had on their personality. Diana said she sees depression as an illness largely because of the literature she has read, but also expressed how she had felt “disappointment to see myself changing into someone else that I don’t even like”. Although she placed depression squarely in the illness category, she was painfully aware of its reach into her personality. Lisa Robinson defines the self as “the thinking, knowing, feeling part of the human organism which deals with the world” (Reference Robinson1974: 19), and Donna Czuchta and Barbara Johnson (Reference Czuchta and Johnson1998) recognise that it is precisely because mental illness affects those human aspects that it is capable of shaping the self. This is why depression cannot be just an illness, as it affects how an individual thinks and feels about him or herself, the world and his or her future. Of course, more physical conditions and illnesses can also affect these aspects of the self, but the effect can be quite pervasive in the case of depression as it directly impacts an individual’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours – the very stuff that the self is made of.

I could certainly understand why these women came to view depression both as an illness and as a part of their self in nuanced ways. Yet these women were a subset of the whole, so I wanted to delve deeper into their stories to see if there was something that might have helped to draw them towards this particular view rather than another. I found the answer in their family history, or at least their interpretation of it. Nearly all of those who view depression as “an illness that is part of me” and all those who view it as “a part of me developed by the illness” said they had some family history of depression or bipolar disorder.6 On one level, it is not surprising that a family history of depression or bipolar disorder might lead one to these viewpoints. When I asked if they believed that genetic factors played a causal role in their depression, many cited whether or not another family member had also been diagnosed with unipolar or bipolar depression as a justification for their belief. As family history can be seen as closely linked to inherited genetic factors, and genetics in turn is implicated in the biomedical model of depression, it is easy to see how a family history of unipolar or bipolar depression can lead one to view it as an illness.7 Indeed, the majority of those I interviewed who described unipolar/bipolar depression mainly as an illness reported that they had some family history of it. Earlier, Miriam invoked her family history as a reason for why she views depression as both an illness and a part of her self (although family history was sometimes also used to justify a view of depression as an illness that is separate to the self rather than part of it). For women such as Miriam, Wendy and Bridget, locating depression in their genes, chemicals or hormones was seen as integrating, rather than isolating, depression as part of the self. Miriam illustrates this view:

So has your view of depression changed over the years?

[…] I’ve always felt that it’s just a part of me – that it’s hard-wired. It’s like having a hand […] it feels as solid as any part of my body … there is a little chemical bit that’s just part of my brain that’s not fixable.

Joseph Dumit (Reference Dumit2003) makes a demarcation between “genetic” disorders and “brain” disorders, claiming that individuals are more inclined to see the latter as part of their self than the former. However, women like Wendy, Miriam and Bridget challenge this demarcation as they include both their genes and their brain within their self-concept.

Genes and the brain were not the only physiological aspects that influenced the individual’s self-concept. Bridget cited the number of episodes she experienced and her reactions to physiological and psychological stresses as reasons for why she feels that depression is so much a part of her self:

I know different people will react to a situation in different ways. Some people will go through things I’ve gone through and not get depressed and I’m not one of those people. And I think it’s something to do with the way I react to psychological stress, but also I think physiological stresses. Because I think, to me it’s really interesting that hormone changes with both my children and pregnancy changes, the hormone changes in pregnancy, or that’s what I think it is, have always triggered my depression. Although maybe it’s the physical effects of being pregnant – you know, the morning sickness. But even when the morning sickness goes the depression doesn’t stay so …

So I guess despite the hormonal triggers or physical triggers, you think it’s still a part of your persona as you say?

Yeah, I honestly don’t think it’s just chemical. I don’t think it’s purely chemical that I get lower levels of serotonin and noradrenalin and that means I get depressed and you give me tablets and I get better. I don’t think it’s that simple.

Bridget could easily have viewed depression as an illness that is separate to her self, having linked her depressive episodes to her pregnancies so strongly. Yet what struck me about Bridget’s explanation was that the self, for her, is both physiological and psychological:

I think [depression is] part of who I am, I think, much as I’d like it not to be […] I think it’s a part of my physiological and psychological persona […]

I don’t think, you can’t say there’s a medical physiological model, for me anyway, or there’s a psychological model. I think it’s an interplay of factors […]

In this way, Bridget resists the mind–body dichotomy. It is not new to conclude that a unique reaction to events or circumstances may point to a locus of depression within the individual. However, to conclude that a unique reaction to physiological stresses indicates the same thing (rather than that the depression is a result of a “biochemical imbalance” that is separate from the self) implicates both the mind and the body in the concept of the self, rather than separate in the Cartesian sense. Bridget’s view, as well as the view expressed by Miriam and Wendy earlier, departs from the Western tendency to conceptualise the body as separate to the self. Instead, they include the physical, not just the spiritual, as intrinsic to the self.

Is It Me or the Illness?

It is striking that most of the women I interviewed spoke candidly about how they struggled with whether certain aspects of their thoughts, feelings and behaviours belong to themselves or to depression or bipolar disorder – that is, they would often raise the issue of whether those characteristics were simply manifestations of their “illness” or a part of who they are, without any prompting. They confided that at times they were unsure whether they were really entitled to feel guilt-free for behaviours which they have been told or read are symptoms of depression or mania and whether the biomedical explanation was simply providing them with an escape from responsibility.

Thoughts, feelings and behaviours which have been labelled as part of a psychiatric illness can also be seen as part of the self. As discussed earlier, many interviewees expressed this view. However, the terms “illness” and “self” were sometimes used as though they are mutually exclusive. Classifying characteristics as either belonging to illness or to the self may have implications for responsibility. The struggle to categorise certain thoughts, feelings and behaviours usually raised a slew of issues surrounding control and responsibility, the self and what defines an illness. Participants openly expressed their difficulties in assigning responsibility for their actions, or indeed, in calling their actions their own, and in taking credit for their recovery. They expressed doubts regarding the biomedical narrative for depression and its implied separation of physical processes, which cause the illness, from the emotional/mental processes, which supposedly constitute the self. Gina is one of those who struggled to distinguish one from the other:

Why do you think it was harder to come to terms with the bipolar diagnosis than the depression [diagnosis]?

[…] When I got bipolar diagnosed, I thought there’s a whole new set of symptoms – there’s a whole new raft of information that I need to learn now. I think it felt like I didn’t know myself anymore. I think that was the difficulty. It felt like I didn’t know myself anymore and it felt like I didn’t know what was me and what was the disease. I think that was another big difficulty and another thing that I found actually really difficult for a very long time was actually teasing out what was personality and what was pathology. And I still have quite a hard time with that.

Many of the women I interviewed tried to identify why they had difficulty distinguishing the self from sickness, or indeed why they felt the need to make such a distinction in the first place. While their explanations varied, there were some common themes throughout. The most popular reason for questioning whether depression can be separated from the self was that the interviewee felt she had had depression for so long that it was difficult to determine whether her character had changed due to depression or simply due to the passage of time. This dilemma may be emphasised by the fact that the average age of onset of depression for these women was during adolescence, when it is not unusual for an individual’s character to change as they entered adulthood. For some women, it was also difficult to establish exactly when depression began in the first place, and therefore where the line is between the self and sickness – if there even is one at all. Evelyn is one of the many women who articulated this uncertainty:

Do you think depression has changed you as a person?

Well given that I couldn’t really say when it began … Would I be different if I didn’t have negative thoughts? Well yes, but that would be a change of personality. It would be a change in how I dealt with things, how I related to people.

Some women stated that sometimes they make a conscious distinction between what belongs to the self and what belongs to the illness based on personal preference. The following quotations are from women who have chosen what constitutes part of their self and what does not, acknowledging that the views they espouse do not necessarily reflect some underlying truth but are rather a reflection of what they would rather own and disown. Quite often, their preference was to shunt certain less desirable traits and behaviours away from the bounds of the self and into the confines of the illness (here understood as separate from the self) in order to dissolve allegations of personal responsibility for their behaviours. By doing so, they render it just as nonsensical to blame the individual for these “symptoms” of depression or mania as it is to blame an individual for getting the flu. Bridget and Miriam illustrate this view:

Bridget: […] I actually think I’m much lazier as a consequence of being depressed over the years. But I might just be blaming it because it’s easy to blame it. It could just be me, you know.

Miriam: I wanted [depression] to be something chemical that could be fixed. Or that could not possibly be construed as my fault.

In this way, many struggled to try to separate their depression or mania from their self and felt that assigning more blame to biology was a way of avoiding guilt for their behaviours. That this struggle with responsibility was seen across the board, and often with little prompting, highlights it as a major issue in an individual’s experience with depression. The struggle has also been highlighted in studies such as that conducted by Jennifer Wisdom and colleagues, who stated that such women experienced a “duality of selves” whereby conceptions of “their real, authentic selves” were presented as dichotomous to their “alternate selves” which “were seen as part of who they were, but were separated as parts that they did not much like or were ashamed to show the world” (Reference Wisdom, Bruce, Auzeen Saedi, Weis and Green2008: 491). However, I see these narratives as more than an expression of a “duality of selves”, but as an expression of doubt about the biomedical narrative. Interviewees articulated this struggle regardless of whether they view depression as an illness or as something else. Even those who purported to espouse the biomedical narrative of depression showed that they were not entirely convinced of its division between the self and sickness when it came to depression and self-determination. This resistance to the biomedical narrative was also apparent in Simone Fullagar’s study, in which she reports that “… despite the dominance of biomedical accounts, very few women attributed their recovery solely to medication or understood depression as singularly caused by a chemical imbalance” (Reference Fullagar2009: 403). Instead, views of the self within depression are constantly being negotiated and in flux or, as Dumit states, “they have entered into a relationship with their brain that is negotiated and social” (Reference Dumit2003: 46).

In Speaking of Sadness, David Karp sees the struggle between the self and illness more as one in which people attempt to explain their depression as biologically or environmentally caused. He writes, “[i]n the end, nearly everyone comes to favour biomedically deterministic theories of depression’s cause […] This is partly a result of their gradual commitment to a medical version of reality. It is also a result of the intrinsic nature of depression itself” (Karp, Reference Karp1996: 31). He then goes on to describe an experience also described by several of the women I interviewed – that once the depressive thought pattern is set in place, biology seems to take over and maintain the cycle. Although Karp’s study is now somewhat dated, it is worthwhile presenting it here to show how these previous views contrast with those I encountered. I suggest three modifications/updates to Karp’s statement. First, although the nature versus nurture debate did figure in my interviews to a certain extent, the choice was not always between the two. It was not uncommon for the individual to state that the main cause of her depression was probably her personality, and this was not necessarily situated in her biological makeup or blamed on her upbringing – it was simply something she was born with but also subject to change. Second, biomedical deterministic theories of depression’s cause were certainly not favoured by the women I interviewed to the extent that they were in Karp’s. This may be a reflection of the change in lay beliefs between then and now, or the different geographical locations, or both. The biomedical theory, rather than being favoured as the primary cause of depression, was in the majority of cases tentatively invoked as the preferred cause when the question of where to assign responsibility was raised. Perhaps it is now simply a rhetorical device, but certainly, one must not ignore the moral work that the illness model does, and which several women openly acknowledged, in exonerating the individual of responsibility for certain behaviours. Third, while the feeling that one’s mood had gained a momentum which felt out of one’s control may provide a clue as to the underlying workings of depression, it does not serve as evidence for an “intrinsic biomedical nature”. That, unfortunately, still remains a mystery. Some of the differences between those I interviewed and those whom Karp interviewed may be culturally informed. Both Ilina Singh (Reference Singh2002) and Natasha Mauthner (Reference Mauthner2002) report that biomedical narratives of depression were much more popular among their US interviewees than their UK counterparts.

Debbie’s statement hints that there is a degree of self-fashioning involved in creating a narrative of depression:

What do you think has changed you?

I think, oddly, it’s just as simple as having to talk to other people about it has changed me, because like I said, it made me rationalise it more and it made me see it as something which is separable from me. Even though I see it as very much a part of me, when it gets to be too much I can kind of step out of myself. It’s like you can pick and choose. I know that that’s probably not the most sensible thing to do, but yeah I don’t know. It kind of is part of me and it isn’t part of me. When it gets out of control, I’d rather it wasn’t.

Experiences of depression have a social reference point, and the retelling of these experiences reflects this. A similar point is made by Arthur Kleinman, who highlights that narratives of illness are part of a life story and play a particular role within it. Narratives can create sense of loss, or act like a myth that reaffirms one’s core values in the face of adversity (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1988a). Nevertheless, Debbie and Annette were aware of the moral work that their particular narrative was doing. As Kleinman, notes, their reflexivity is not something we often expect of patients:

[t]he chronically ill are caught up with the sheer exigency of their problems; what insight they possess into its structural sources and consequences they are not expected to voice. This is a social fiction of the illness role. The patient, in order to legitimately occupy that role, is not expected to be consciously aware of what she desires from it, what practical uses it has.

Not only do the women I spoke with show how reflexive patients can be, they also show what roles their particular views of depression play in their life story and view of their self.

I now turn to another area in which the inner conflict of the self versus the illness becomes apparent. After listening to accounts of how some of the women experienced mania, I was struck by their similarities with schizophrenia and Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). One such case was that of Annette, a softly spoken young mother who described how she suddenly and unexpectedly began to hallucinate. What then followed was, as Annette described, “an absolute hell” of delusions and paranoia:

I couldn’t sleep for about four days, couldn’t eat anything, I became delusional. I thought I was God, I thought my husband was the devil, I was screaming and shouting, doing things that I wouldn’t normally do. My husband got some old friends of ours up to help because he was obviously finding my behaviour hard to cope with because it was totally out of character. I remember taking all my clothes off in front of one of our friends, which I wouldn’t normally do … or shout abuse or scream, you know. I wouldn’t normally behave like that. I was out of control.

Following medication, Annette recovered from her manic state and struggled to understand what had happened. She felt ashamed and embarrassed and was at a loss as to how to explain behaviour so out of character. At one point she describes who she was during her manic state as “an out-of-control Annette”, but at another point says that she was not really herself.

Jeanette Kennett and Steve Matthews, in their paper Identity, Control and Responsibility: The Case of Dissociative Identity Disorder (Reference Kennett and Matthews2002), also note the similarity between certain forms of bipolar disorder and DID and would argue that the person during the manic phase was an “out-of-control Annette”. In an exploration of whether it is one self or multiple selves at the heart of these mental illnesses, Kennett and Matthews present an argument that individuals who behave badly in one of these alter ego states are still the same self but in a deluded state. They liken it to the common view that acts committed while drunk are still committed by the same person, but in an altered or deluded state. The differences are first that this alter state is perhaps more extreme in cases of schizophrenia, DID and certain cases of bipolar disorder; and second, that the agent has no control over when the switch between the “normal” and alter state occurs.