Book contents

- The Drama of Memory in Shakespeare’s History Plays

- The Drama of Memory in Shakespeare’s History Plays

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Note on the text

- Introduction: forms of remembering and forgetting in early modern England and on the Shakespearean stage

- 1 Media: oral report, written record and theatrical performance in2 Henry VIandRichard III

- 2 Ceremony: rites of oblivion in Richard II and 1 Henry IV

- 3 Embodiment: Falstaff’s ‘shameless transformations’ in Henry IV

- 4 Distraction: nationalist oblivion and contrapuntal sequencing in Henry V

- 5 Nostalgia: affecting spectacles and sceptical audiences in Henry VIII

- Conclusion: Shakespeare’s mnemonic dramaturgy

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

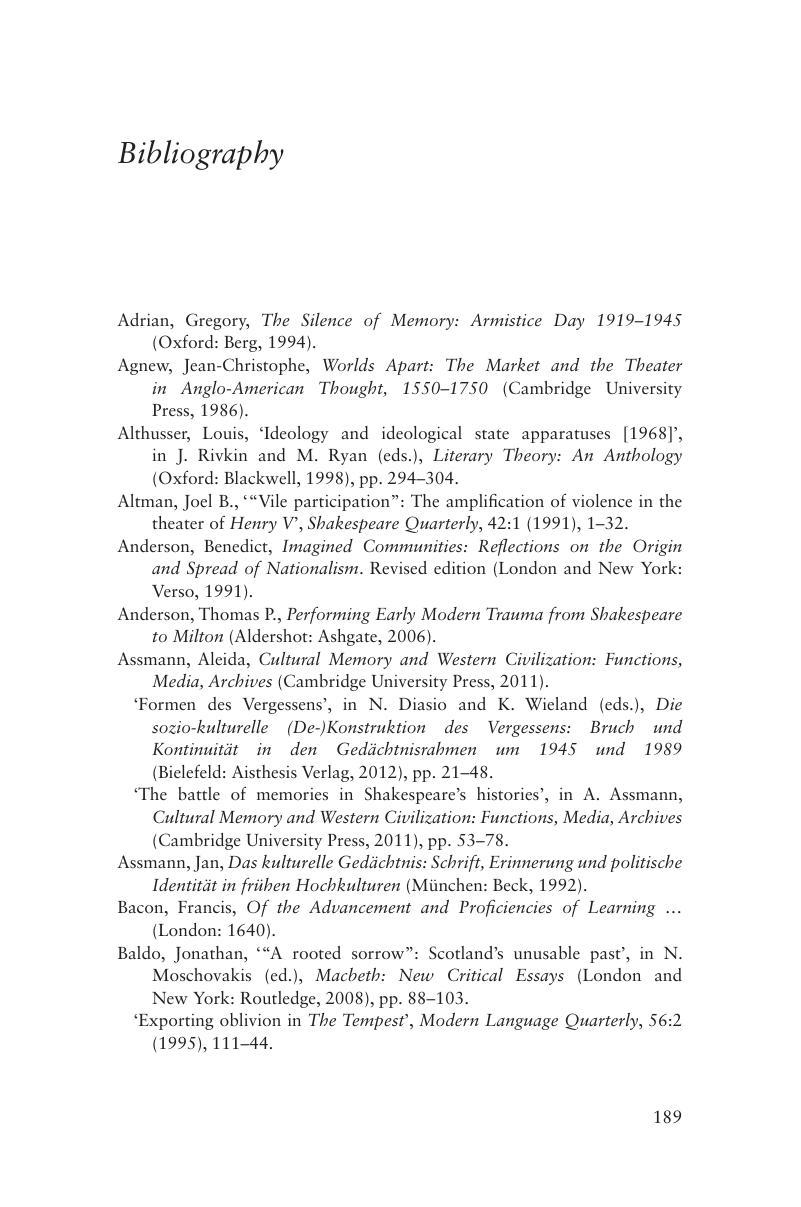

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2015

- The Drama of Memory in Shakespeare’s History Plays

- The Drama of Memory in Shakespeare’s History Plays

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Book part

- Note on the text

- Introduction: forms of remembering and forgetting in early modern England and on the Shakespearean stage

- 1 Media: oral report, written record and theatrical performance in2 Henry VIandRichard III

- 2 Ceremony: rites of oblivion in Richard II and 1 Henry IV

- 3 Embodiment: Falstaff’s ‘shameless transformations’ in Henry IV

- 4 Distraction: nationalist oblivion and contrapuntal sequencing in Henry V

- 5 Nostalgia: affecting spectacles and sceptical audiences in Henry VIII

- Conclusion: Shakespeare’s mnemonic dramaturgy

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Drama of Memory in Shakespeare's History Plays , pp. 189 - 204Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015