By way of censure and reproach of the impetuous style of Timarchos, he [Aeschines] alleged that a statue of Solon, with his himation drawn round him and his hand enfolded, had been set up to exemplify the self-restraint of the popular orators of that generation. People who live at Salamis, however, inform us that this statue [andrias] was erected less than fifty years ago. Now from the age of Solon to the present day about two hundred and forty years have elapsed, so that the sculptor who designed that disposition of drapery had not lived in Solon’s time – nor even his grandfather. He illustrated his remarks by representing to the jury the attitude of the statue; but his mimicry did not include what, politically, would have been much more profitable than an attitude – a view of Solon’s spirit and purpose, so widely different from his own. When Salamis had revolted, and the Athenian people had forbidden under penalty of death any proposal for its recovery, Solon, accepting the risk of death, composed and recited an elegiac poem, and so retrieved that country for Athens and removed a standing dishonor.

Not all Greek portraits of the Archaic and Classical periods represented living subjects or subjects deceased within living memory. As we have already seen, portraits of long-dead Olympic victors began to be dedicated already in the fifth century. These were variously used by victors’ home cities to claim the symbolic capital afforded by their arete; to solidify the case for their worship as heroes or gods; or by relatives to emphasize their genealogical connections with earlier victors (the Daochos group). But the practice of retrospective portraiture was more widespread, especially in the fourth century bc. Perhaps the best known Greek retrospective portraits are the bronze statues of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides set up in the precinct of the Theater of Dionysos in Athens on the initiative of the Athenian politician and orator Lycurgus of Boutadai at some point between Athens’ defeat by Philip II at the battle of Chaironea in 338 bc and Lycurgus’ own death in 324.1 The three fifth-century playwrights in the Theater of Dionysos are worth singling out because they are instructive in several respects. There is a strong documentary link between their portraits and Lycurgus’ simultaneous proposal calling for official texts of these authors’ plays to be transcribed and preserved as the basis for future performances (ps.-Plut. X orat. 841–2): portraits of Greek authors and the formation of literary canons go hand-in-hand.2 Plutarch mentions an official enactment of the Athenian demos as the mechanism authorizing the three portraits, a valuable attestation since the circumstances surrounding the creation of nearly all other retrospective Greek portraits, in Athens and elsewhere, remain murky. Lycurgus’ portraits of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides also provide a welcome chronological fixed point on the cusp of the Hellenistic period for the broader cultural practices that fostered retrospective portraits. As has long been remarked, the surviving speeches, legislative enactments, and other initiatives associated with Lycurgus and his circle in Athens exemplify a thoroughgoing attitude of retrospection, consciously looking backward toward Athens’ illustrious fifth-century history.3

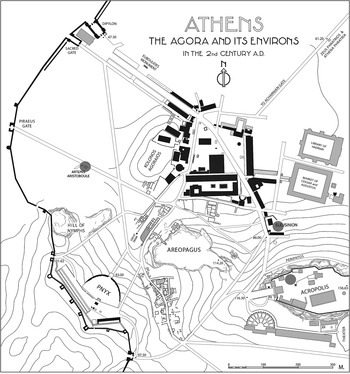

The Athenian portrait of Lycurgus himself illustrates the distinction between posthumous honors and retrospective portraits. Lycurgus was posthumously awarded highest honors, including a portrait statue, by the Athenians in 307/6, fifteen years or so after his death, as attested by both the inscribed decree (IG II2 457) and a base for his portrait (IG II2 3776).4 The late fourth-century portrait of Lycurgus can best be explained as a delayed honor. In contrast, the portrait of Socrates in the Pompeion in the Kerameikos supposedly made by Lysippos (Diog. Laert. 2.5.43) both reaches back into the period before routine portrait honors and represents a subject that would never have received an official portrait in Athens in the first place: both facts make Socrates’ portrait in the Pompeion retrospective.5

For the Greeks, retrospective portraits performed a variety of overlapping documentary functions to be explored in this chapter. Portraits of authors were desirable wherever those authors’ works were read: we are accustomed to studying Roman marble copies of such portraits, but from the fifth century bc onward literary portraits served the important function in Greek culture of shoring up literary biographies and attributions. Their contexts and locations placed literary figures and laid claims to associations with them. A major goal of this chapter is to pursue more closely the possible relationships between retrospective portraits and what we might term retrospective historical documents. Christian Habicht, in a ground-breaking article published in 1961, called attention to a series of documents related to fifth-century Greek history from the Persian Wars through the Pentacontaetia that make their first appearance in Athenian forensic speeches and inscriptions of ca. 360–330 bc. Retrospective historical documents, like retrospective portraits, were being fabricated in the fourth century to fill gaps in the historical documentation of the sixth and fifth centuries, including the Persian Wars. Like retrospective documents inscribed on stone, some retrospective portrait statues of the late Classical and early Hellenistic periods seem to be in dialogue with canonical fifth-century historical texts, and even to challenge their testimony.

Retrospective Portraits of Poets: Anacreon of Teos on the Athenian Acropolis

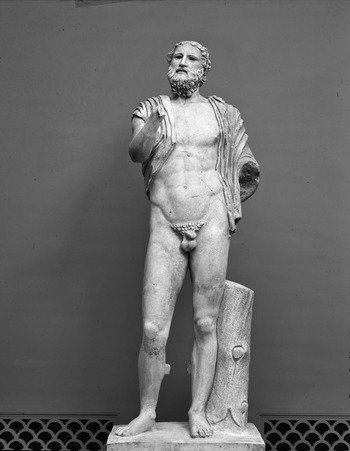

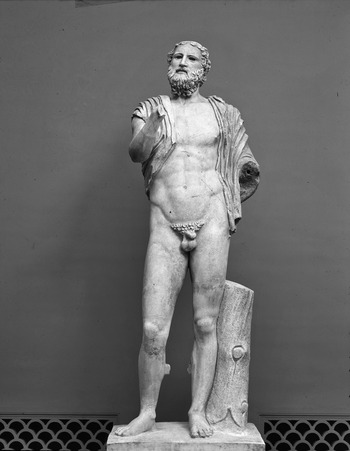

We have already encountered fifth-century portraits of poets that treated them as if they were savior gods: those of Homer and Hesiod in one of Mikythos’ dedications at Olympia. In fifth- and fourth-century Greece, retrospective portraits of poets were also used to perpetuate the fame of their works and to claim ownership of their memory. The Roman marble portrait of the late Archaic poet Anacreon of Teos in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen [Figure 48] is a rare example in which a Greek subject’s whole body, rather than just the head, has been reproduced. The type is otherwise represented by several fragmentary Roman marble herms and disembodied heads of lesser quality.6 On the basis of one herm with the inscribed name label Anakreon Lyrikos (The Lyric Poet Anacreon), the lost Greek original behind the Roman type has been connected with a passage in Pausanias describing a portrait of Anacreon “in his cups” on the Athenian Acropolis (1.25.1):

There are on the Acropolis of the Athenians [portraits] of both Perikles the son of Xanthippos and of Xanthippos himself, who fought against the Persians at Mykale. But the statue of Perikles is located elsewhere, while near the one of Xanthippos stood Anacreon of Teos, the first after Sappho of Lesbos who wrote poems mostly erotic in nature; his pose is like that of a man singing while drunk.

The portrait of Anacreon on the Athenian Acropolis, if it has been accurately reconstructed from the Ny Carlsberg statue, has been dated to ca. 450–440 bc by Zanker; Anacreon died in ca. 480 bc. According to the post-Classical biographical tradition, Anacreon and other refugees fled Teos in Asia Minor in the wake of the Persians and went to Abdera in Thrace (Strabo 14.1.30). Anacreon’s presence at the court of the tyrant Polycrates on Samos before Polycrates’ death in 522 bc is attested already in the fifth century by Herodotus (3.121). Peisistratos’ son Hipparchos brought Anacreon to Athens during the tyranny of his brother Hippias (Plato [Hipparch.] 228b–c and Plato Chrm. 157e).7 Zanker and Shapiro have noticed that the Ny Carlsberg portrait transforms Anacreon from an Ionian poet performing in elaborate eastern dress, seen on late Archaic Athenian vases, into a high Classical Athenian with an idealized appearance and minimal garments.8 Shapiro has argued that the lost portrait on the Acropolis, like the Ny Carlsberg statue, represented Anacreon as the poet par excellence of the Athenian symposium: in this view, the infibulation (kynodesmos) of Anacreon’s exposed penis, perhaps the oddest detail of the statue, called to mind Anacreon’s restraint in both drinking and erotic attachments.9 But kynodesmos was also practiced by Greek athletes, and Anacreon’s nudity would have linked him visually with both athletes and warriors represented by other fifth-century portraits on the Acropolis.

What was the political significance of representing Anacreon in this guise on the Acropolis in ca. 450–440 bc? Despite the absence of an inscribed base, diametrically opposed interpretations have been offered: either the portrait was dedicated on the Acropolis by members of the conservative opposition to Perikles, or by Perikles’ supporters or Perikles himself.10 A more promising approach might be to see a retrospective portrait of Anacreon on the Acropolis, set up around the time of the transfer of the treasury of the Delian League from Delos to the Acropolis in 454 bc, as a gesture commemorating the connection between Ionia and Athens in the late Archaic period while obscuring the role of Peisistratos’ sons in bringing Anacreon to Athens.11 Anacreon’s connection with Athens was further reinforced in the fourth century and the Hellenistic period by attributing to him a group of late Archaic and early Classical epigrams inscribed on herms in Athens and Attica (Anth. Pal. VI 134–45), again without reference to the Peisistratids.12 The Acropolis portrait remembered the period of the Peisistratid tyranny without commemorating Peisistratos or his sons. Though the timing of Anacreon’s portrait may be explained by the important role of the performance of Anacreon and other Archaic Greek lyric poets in Periklean musical culture, seeing Anacreon on the Acropolis reminded viewers less of Perikles than it reminded them of the Peisistratid tyranny.13

Kallias, Son of Hipponikos, and the Fifth-Century Peace with Persia

Retrospective portraits of other subjects in Athens show clear signs of having been inspired by written documents; the portraits in turn served as tekmeria reinforcing these documents’ authority and authenticity. The connection between a retrospective portrait statue and a retrospective document appears most clearly in the case of Kallias, son of Hipponikos of the deme Alopeke, brother-in-law of Kimon, a member of the priestly genos Kerykes who served as dadouchos (torch-bearer) of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis. Fourth-century sources credit him with negotiating the peace with Persia in 449 bc, after the Athenian defeat of the Persian navy off the coast of Salamis in Cyprus.14 Pausanias (1.8.2) saw his portrait among a cluster of statues in the Athenian Agora, somewhere between the eponymous heroes monument and the temple of Ares. In the Agora in the fourth century, statues of gods and heroes functioned as nuclei that attracted portraits:

After the statues of the eponymoi are images of the gods, Amphiaraos and Peace [Eirene] carrying the infant Wealth [Ploutos]. Here Lycurgus, son of Lykophron, stands in bronze, and Kallias, who, as most of the Athenians say, made peace with Artaxerxes the son of Xerxes on behalf of the Greeks. Here too is Demosthenes, whom the Athenians forced to withdraw to Kalaureia, the island before Troizen, but having received him back later they forced him out again after the disaster at Lamia.

As we have already seen, the honorific portrait of Lycurgus was erected in 307/6; Demosthenes’ portrait dates to 281/0 bc.15 Since the Athenians gained control over Oropos and its sanctuary of Amphiaraos only in 335, the god/hero Amphiaraos’ image in the Agora should logically date to the Lycurgan period.16 The clearest thematic link in the grouping, and the key to the date of the Kallias portrait, was the connection between the personified Peace and Wealth group and Kallias. The Athenians founded the cult of Peace by setting up an altar for her in the Agora in 375/4 bc, twelve years after the King’s Peace (also called the Peace of Antalkidas) had put a temporary end to conflict between the Greeks in 387/6 (Xen. Hell. 5.1.31), and the same year that Timotheos won a victory over the Spartans at Alyzeia.17 Several Roman marble versions of the matronly Peace holding the infant Wealth in her arms match a representation of the statuary group on a Panathenaic amphora of 360/59 bc. On the basis of two different passages in Pliny (HN 34.51 and 87), the bronze original of Peace and Wealth seen by Pausanias has been attributed to the elder Kephisodotos and dated soon after the altar, perhaps in 372 or 371 bc.

Another reason for supposing that Kallias’ portrait was a retrospective one, beyond the fact that the altar and personification of Peace with which it was associated date to the 370s, is that Kallias’ mid-fifth-century peace treaty with Persia seems to be a retrospective document. Thucydides makes no mention of any such peace agreement between Greeks and Persians ending the Persian Wars, and Herodotus (7.151) only refers obliquely to Kallias’ presence at the court of Artaxerxes in Susa.18 The peace of Kallias with the Persians dated to 449 bc, after Kimon’s ostracism in 462/1 and his death in ca. 450, makes its first appearance in Attic historiography only in the aftermath of the King’s Peace of 387/6 (Diod. Sic. 12.4, probably using the fourth-century Ephoros as a source; Aristodemus FGrH 104 F13; and the Suda, s.v. Καλλίας). Theopompos of Chios (FGrH 115 F153–4), in a preserved fragment of his lost universal history written in the age of Philip II and Alexander, noted that the version of the peace treaty he saw on a stele in Athens could not date from the mid-fifth century because it was inscribed in the Ionian alphabet, adopted in Athens for official state documents in 403/2 bc.19 Regardless of what Kallias himself did or did not do, and when, the evidence suggests that the Peace of Kallias as a document inscribed on a stele dates to the fourth century. The inscribed stele and the portrait statue were probably displayed together, and both should date after the foundation of the cult of Peace and the statue of Peace and Wealth in the 370s bc.20

Solon in the Agoras of Salamis and Athens

Not every gap was thought to be worth filling with either retrospective documents or retrospective portraits: the memory of some earlier individuals lived on in oral tradition without fourth-century interventions. Kimon, for example, continued to be remembered in association with the plane trees in the Athenian Agora and the Academy (Plut. Cim. 13.8), the south wall of the Acropolis (Nep. Cimon 2.5 and Plut. Cim. 13.5), and the Stoa Poikile in the Agora, the construction of which was popularly attributed to his brother-in-law Peisianax. The epigrams inscribed on three herms set up by the Athenians in the Agora to commemorate Kimon’s victory at Eion on the Strymon river left room in the fourth century (Aeschines 3.183–6) for speculation that Kimon had asked to be mentioned by name in the monument’s inscription, but that his request had been denied.21

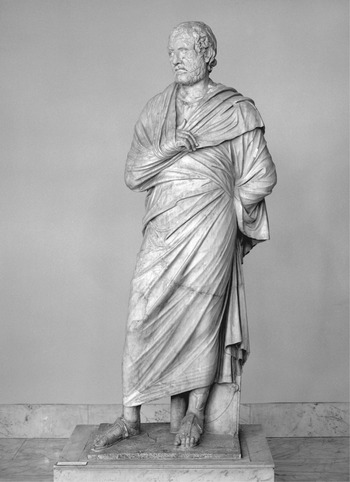

In the case of the portrait of Solon in the agora of Salamis, a figure from the past was represented in the guise of a contemporary honorific portrait. Aeschines (1.25) described the pose of Solon’s statue, standing with its arm wrapped within its himation, as evidence for Solon’s demeanor when he addressed the citizens of Athens. Demosthenes (19.251) countered in a slightly later speech (delivered in 343 bc), quoted in the epigraph to this chapter, that this particular portrait of Solon was new and therefore useless as evidence for what Solon really looked like. Demosthenes’ unmasking of a retrospective portrait of Solon provides a valuable attestation for retrospective portraits of subjects other than poets in Athens.22 Solon’s portrait, as Aeschines described it, was strikingly similar to the “himation man” portrait of Aeschines himself, known through Roman marble copies [Figure 49].23

In order to determine why there was a retrospective portrait of Solon in the agora of Salamis in the first place, we need to look more closely at the context in which Demosthenes mentions the statue.24 In the course of his prosecution of Aeschines for his conduct on an Athenian embassy to Philip of Macedon, Demosthenes (19.251–5) contrasted Aeschines’ supposed appeasement of Philip with Solon’s willingness to persuade the demos to go to war over the loss of the island of Salamis to nearby Megara. The long Solonian elegy on Salamis that Demosthenes refers to survives only in three short fragments (Solon frag. 2, Noussia-Fantuzzi Reference Noussia-Fantuzzi2010). It is paraenetic, urging the Athenians onward to reclaim the island of Salamis from Megara:

Solon’s elegy served as the basis for a biographical tradition that Solon himself had led the Athenians in a military campaign against Megara over the ownership of Salamis, a conflict otherwise associated with the tyrant Peisistratos later in the sixth century.26 The portrait in the agora of Salamis reinforced the attribution of the Salamis elegy to Solon. Indeed, a portrait of this particular subject in this particular place would have made little sense without the elegy: it was like setting up a portrait of Tony Bennett in San Francisco.

A second portrait statue of Solon, this one standing in the Agora of Athens, is mentioned elsewhere in the Demosthenic corpus ([Dem.] 26.23), in a speech against Aristogeiton (a relative of the Tyrannicide of the same name) dating probably to the later 330s bc. The speaker invokes this portrait specifically in connection with Solon’s laws and interprets it as honorific:

It is preposterous that your [the Athenian demos’] ancestors faced death to save the laws from destruction, but that you do not even punish those who have offended against the laws; that you set up in the Agora a bronze statue of Solon, who framed the laws, but show yourselves regardless of those very laws for the sake of which he has received such exceptional honor.

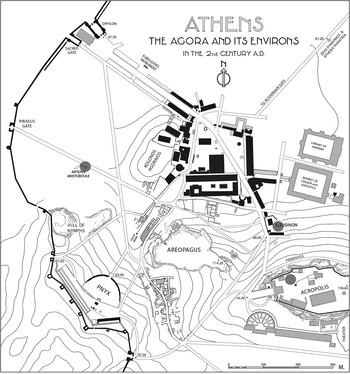

Pausanias (1.16.1) locates this statue of Solon in front of the Stoa Poikile on the north side of the Agora [Figure 50]. Since the Stoa Poikile was not built until the second quarter of the fifth century, the portrait of Solon in the Athenian Agora must also be retrospective and must date sometime between the mid-fifth century and the 330s bc.

Demosthenes mentions Solon’s portrait in the same breath as Solon’s laws: the so-called lawcode of Nikomachos, the codification of the Athenian sacred calendar together with some of the laws attributed to Solon, was inscribed on stelai displayed in the Stoa Basileios in the Agora between 410 and 399 bc. But if the restoration of the Athenian democracy and the codification of its laws was the occasion for setting up Solon’s portrait, then why did it stand in front of the Stoa Poikile rather than the Stoa Basileios, where the laws themselves were displayed? Since the siting of portrait statues, both contemporary and retrospective, within the Agora was otherwise deliberate, it is hard to accept that the placement of Solon’s was without significance. In this context, it is worth considering Plutarch’s (Sol. 8.1–3) account of how Solon came to compose and recite his elegy on Salamis:

Once when the Athenians were tired out with a war which they were waging against the Megarians for the island of Salamis, they made a law that no one in future, on pain of death, should move, in writing or orally, that the city take up its contention for Salamis. Solon could not endure the disgrace of this, and when he saw that many of the young men wanted steps taken to bring on the war, but did not dare to take those steps themselves on account of the law, he pretended to be out of his head, and a report was given out to the city by his family that he showed signs of madness. He then secretly composed some elegiac verses, and after rehearsing them so that he could say them by rote, he sallied out into the marketplace of a sudden, with a cap upon his head. After a large crowd had collected there, he got upon the herald’s stone and recited the poem which begins,

I myself came as a herald from lovely Salamis,

Putting forth a song in well-ordered verses in the place of a speech.

This poem is entitled “Salamis” and contains a hundred very graceful verses. When Solon had sung it, his friends began to praise him, and Peisistratos in particular urged and incited the citizens to obey his words. They therefore repealed the law and renewed the war, putting Solon in command of it.

The story current in Plutarch’s time is clearly a biographical fiction.27 The location of the so-called herald’s stone (κήρυκος λίθος) in the Agora remains unknown, and the area in front of the Stoa Poikile where Solon’s portrait must have stood has not yet been excavated.28 All the same, it is worth suggesting that the retrospective portrait of Solon in the Athenian Agora was set up before the 330s bc with a view toward Solon’s Salamis elegy rather than Solon’s laws. The location and appearance of the portrait may have inspired the biographical tradition that Solon had recited his elegy to the Athenians assembled in the Athenian Agora, a version of the story fully developed by Plutarch’s time.29 Solon may have been represented in both the agora of Salamis and the Agora of Athens, not as lawgiver, but as a poet and the author of the Salamis elegy.

Remembering Infamy: Kylon of Athens and Epimenides of Knossos

Like the portrait of Anacreon, other portraits of Archaic and fifth-century subjects on the Athenian Acropolis, notably that of Perikles’ father Xanthippos, the Peloponnesian War strategos Phormion, and the paired portraits of the strategos Tolmides and Theainetos, could be retrospective.30 One portrait of an Archaic subject there goes against the principle of singling out individuals for their arete: Kylon, the Athenian victor in the Olympic games and son-in-law of the Megarian tyrant Theagenes, whose attempt to become tyrant of Athens in the late seventh century bc failed and resulted in the curse that continued to plague the Alkmeonid genos through the fifth century. Pausanias himself was bewildered to discover a portrait statue of Kylon on the Acropolis:

I have no clear answer for why they dedicated a bronze statue of Kylon despite his having plotted tyranny, but I infer that it was for the following reasons: because he was exceedingly good looking and not obscure with respect to fame, having won an Olympic victory in the diaulos [double foot race] and having married the daughter of Theagenes, who was tyrant of Megara.

Kylon’s attempt to become tyrant of Athens is normally placed ca. 630 bc, after his Olympic victory in 640/39.31 Herodotus (5.71) and Thucydides (1.126) tell different versions of the story, but both situate the main action in the sanctuary of Athena Polias on the Acropolis [Figure 50]; neither mentions the portrait statue. According to Herodotus, when Kylon and his supporters failed to seize the Acropolis, Kylon sought sanctuary at the agalma, presumably the wooden cult statue of Athena Polias inside the Erechtheion. The prytaneis of the naukraroi (presidents of the naval boards) convinced Kylon and his supporters to leave the agalma promising them inviolability, but reneged on their promise and killed them. Thucydides’ account is both more detailed and more precise. In Thucydides’ version, the siege was supervised by the nine archons, and both Kylon and his brother escaped; Kylon’s remaining supporters sought asylum as suppliants at the altar of Athena, not the statue. These suppliants were deceived and killed, some of them at the altars of the Semnai Theai, the “reverend goddesses” or Erinyes, probably the same as the Eumenides worshipped between the Acropolis and the Areopagus from at least the fifth century onward. Both the men who killed the suppliants and their families were accursed as a result of the killing; as becomes clear elsewhere in Herodotus’ and Thucydides’ histories, the curse fell specifically upon the Alkmeonid genos and its leader Megakles.32

The portrait of Kylon has most often been explained as expiating the pollution incurred by the murder of suppliants, much like the two portraits of the fifth-century Spartan regent Pausanias set up in the sanctuary of Athena Chalkioikos in Sparta.33 Yet, in order for such an expiatory portrait on the Acropolis to make sense, Kylon himself would need to have been killed as a suppliant on the Acropolis, and Thucydides claims that Kylon escaped.34 A more serious problem is the date of the statue. Since a bronze portrait is unlikely to have survived the Persian sack of the Acropolis in 480 bc, the statue seen by Pausanias must either be a post-480 replacement, or a monument of the Classical period or later. The same chronological objection applies if Kylon’s portrait was in fact an athletic victor portrait rather than an expiatory one.

The figure that some literary sources mention in connection with the purification of Athens after the Kylonian conspiracy is Epimenides of Knossos in Crete, a religious expert and exegete. His place in the historical narrative of early Athens was the subject of disagreement: Herodotus and Thucydides do not mention him at all; both the Ath. Pol. and Plutarch (Sol. 12.7–9; cf. Conv. sept. sap. 157f–158a) date his purification of Athens a generation after Kylon, in the time of Solon in the 590s bc.35 Plato (Laws 1.642d4–e4), chronologically the earliest source to connect Epimenides with Athens, places his purification of the city nearly 100 years later, around the time of the conflict between the Alcmeonid Kleisthenes and Isagoras at the end of the Peisistratid tyranny in 510, when the Spartan king Kleomenes staged an intervention on the pretext of expelling the accursed from Athens (Hdt. 5.66–76). In either case, Epimenides’ purification of Athens from the Kylonian blood pollution, the likely occasion for setting up an expiatory portrait, took place before 480 bc. There is no obvious post-480 occasion, religious or otherwise, for dedicating a portrait of Kylon on the Acropolis.

As it turns out, there was also a portrait of Epimenides of Knossos in Athens in Pausanias’ time, specifically in the City Eleusinion, the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore located north of the Acropolis and northeast of the Areopagus [Figure 50]:

In front of this temple, where the statue of Triptolemos is too, is a bronze bull as if being led to sacrifice, and there is a seated figure of Epimenides of Knossos, who they say went to the countryside, entered a cave and slept. And the sleep did not leave him before the fortieth year had passed, and later he wrote poetry and purified Athens and other cities.

In addition to ridding Athens and other cities of pollution, by the Roman period Epimenides had become a quasi-legendary, shaman-like figure capable of supernatural feats, much like Aristeas of Proconnesos; like Aristeas, Epimenides too was credited with epic poetry that seems to date to the fourth century bc.36 The fact that Epimenides’ portrait depicted him seated, and the statue’s location in front of the temple of Triptolemos, a building built in the mid-fifth century bc (ca. 480–450), taken together point to a retrospective portrait of the fourth century or later.37 The portrait of Epimenides in the City Eleusinion represented him as a seated poet in the early Hellenistic mode, while at the same time reminding viewers of his association with Athens in the Archaic period.

But what of Kylon’s portrait on the Acropolis? I would explain it as a retrospective portrait of the fourth century or later. The locations of the portraits of Kylon and Epimenides helped to articulate the topography of the Kylonian episode. Pausanias mentions the portrait of Kylon just as he finishes his loop stretching from the eastern entrance of the Erechtheion, along the northern side of the building, ending up at Pheidias’ colossal bronze Athena Promachos located west of the Erechtheion. Though not particularly close to either the cult statue or the altar of Athena Polias that figure in the story of Kylon’s supplication on the Acropolis, the portrait may have looked toward the Areopagus and the area just to the east of it where the altars of the Semnai Theai (Eumenides) were located from at least the 470s bc onward. The portrait of Epimenides in front of the temple of Triptolemos in the City Eleusinion in turn looked southward toward the Areopagus, the altars of the Semnai Theai, and the northern half of the Acropolis where the Kylon statue stood. Though Diane Harris-Cline has argued that the historical accounts of the Kylonian conspiracy, dating to the second half of the fifth century and later, misunderstand the topography of late seventh-century Athens, what matters for the later commemoration of these events is not where they really took place, but where sources of the fifth century and later thought they had taken place.38 The imagined topography took root in the fifth century and was then reinforced by the portraits of Kylon and Epimenides, to the extent that Diogenes Laertius in the third century ad, in his biographical sketch of Epimenides (Diog. Laert. 1.109–11), claimed that the sanctuary of the Semnai Theai had been founded on the Areopagus by Epimenides himself in the course of his purification of Athens. The portraits of Kylon on the Acropolis and Epimenides down below in the City Eleusinion provided what appeared to be fixed points of reference amid a civic landscape that had undergone radical changes since the late seventh century bc.

The Priestess Chrysis in the Argive Heraion

Before the entrance to the late fifth-century/early fourth-century bc temple of Hera in the Argive Heraion, Pausanias (2.17.3) saw a group of portraits of priestesses of Hera near a group of heroes including Orestes, whose statue seems to have been reinscribed as a portrait of Augustus.39 Pausanias noted similar rows of priestess portraits in other Greek sanctuaries, sometimes also near the entrance to the temple, and excavations have turned up late Hellenistic examples from the sanctuary of Artemis Polo on Thasos and elsewhere.40 At the very end of his account of the Heraion (2.17.7), Pausanias mentions another priestess portrait, this one representing Chrysis, the priestess who had burned down the Archaic Hera temple in 423 bc, as we know from Thucydides (4.133). Thucydides (2.2.1) says elsewhere that Chrysis served for fifty-six and one-half years before the temple burned down, and that she was forced to flee Argos after the fire. Pausanias was evidently impressed that, “although so great a disaster had befallen them, the Argives did not take down the statue of Chrysis; it is still in position in front of the burnt temple.”

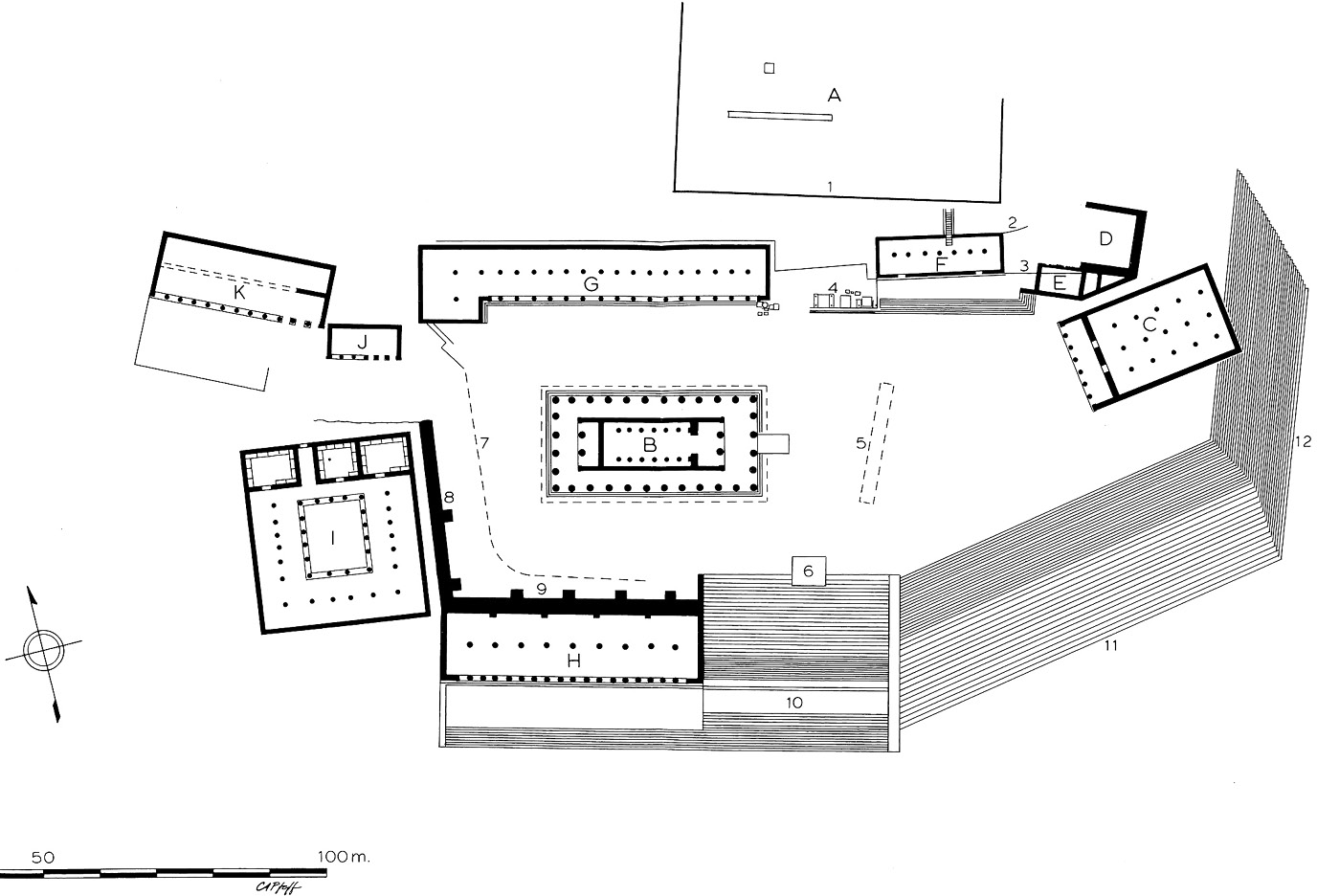

Though the portrait of Chrysis seen by Pausanias in the Argive Heraion has normally been taken at face value as a pre-423 dedication, an alternative scenario is more compelling: that the Argives began to dedicate honorific portraits of priestesses at some point after the rebuilding of the temple in the early fourth century, and eventually added a retrospective portrait of Chrysis near the temple she had so tragically destroyed. The portrait of Chrysis stood in front of the ruins of the burnt temple, while the later priestess portraits Pausanias saw were associated with the second Hera temple still in use in his own time [Figure 51].41 After the legendary Io, Chrysis was the most famous priestess of Argive Hera, thanks to Thucydides; the addition of her portrait would have reminded visitors of a well-known story from the fifth-century history of the sanctuary. The work of the late fifth-century Greek chronographer Hellanicus on the priestesses of Argive Hera, which used the list of priestesses as a panhellenic chronographic framework, also made Chrysis relevant.42 Far from being a contemporary priestess portrait from the fifth century, then, the statue of Chrysis seen by Pausanias in the Argive Heraion can best be explained as a retrospective portrait of the fourth century or later.43

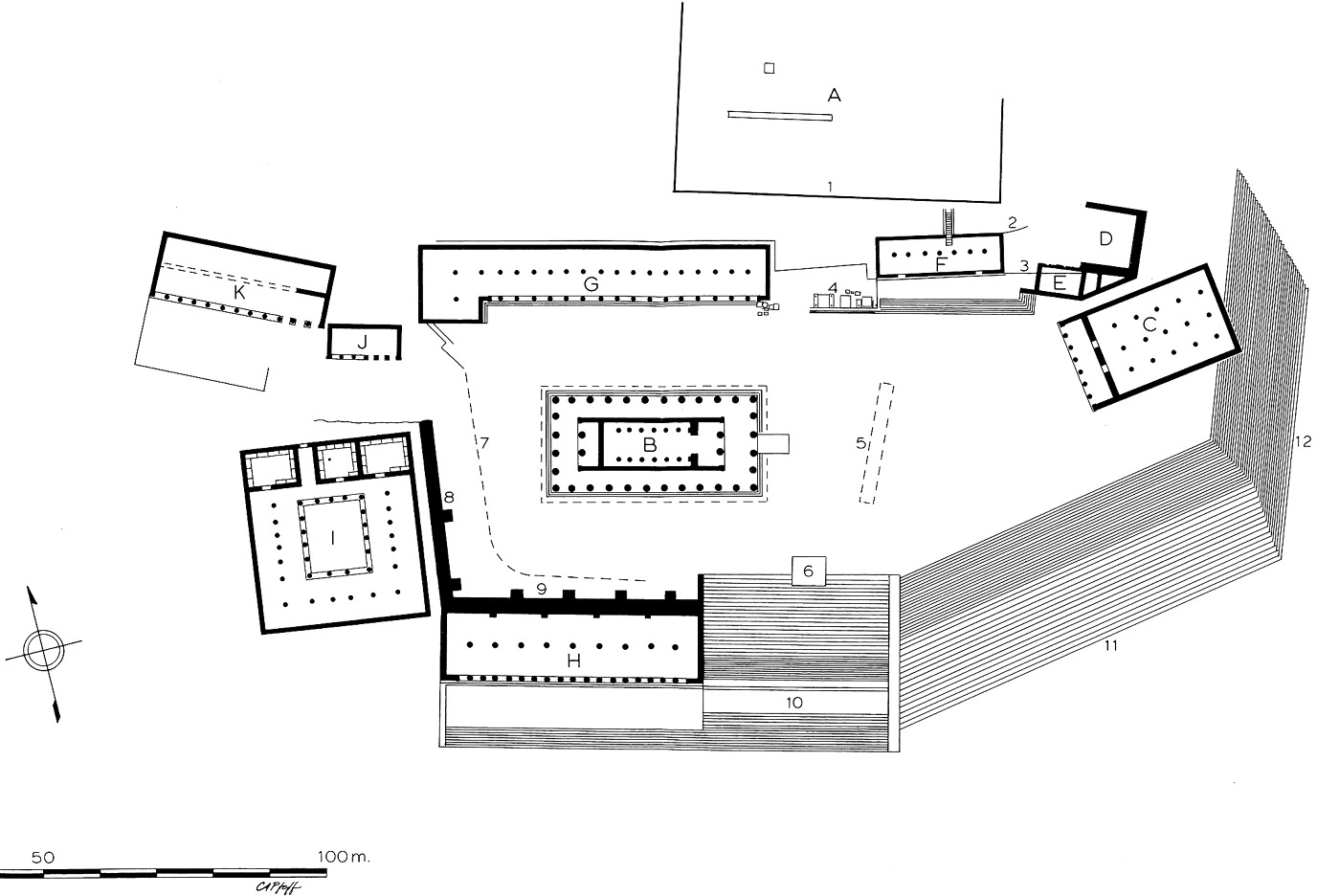

51. Plan of the Argive Heraion by C. Pfaff. The temple of the early fourth century is B on the plan; A marks the location of the original temple, burnt down by Chrysis in 423 bc.

Retrospective Portraits of Persian War Subjects

Just as Herodotus mentions few Greek portraits, so too there seem to have been few portraits among the monuments set up by the Greeks in the immediate aftermath of the Persian Wars of 490 and 480–479 bc.44 Miltiades had been included along with Athena, Apollo, and the eponymous heroes of Athens in the large statue group by Pheidias at Delphi, but the prototypical Persian War dedications at Delphi and elsewhere were colossal divine images in bronze. From the fourth century through the Roman imperial period, the Persian Wars served as a focal point for intensive cultural retrospection.45 It is to these later periods that I would attribute nearly every portrait statue commemorating the events and individuals of the Persian Wars.

Skyllias and Hydna at Delphi

Some portraits of Persian War-related subjects known only from literary sources carry with them a strong suspicion of having been conceived as responses to Herodotus’ Histories, the canonical historical narrative of the Persian Wars. Pausanias (10.19.1) describes a pair of statues in front of the temple of Apollo at Delphi representing a man he calls Skyllis and his young daughter Hydna, divers originally from Scione in northern Greece who fouled the anchors of the Persian ships off the coast of Thessaly, while the Persian fleet was on its way to Salamis:

Beside the portrait of Gorgias is the dedication of the Amphictyons, representing Skyllis of Scione, who, tradition says, dived into the very deepest parts of every sea. He also taught his daughter Hydna to dive. When the fleet of Xerxes was attacked by a violent storm off Mount Pelion, father and daughter completed its destruction by dragging away under the sea the anchors and any other tackle the triremes had. In return for this deed the Amphictyons dedicated portraits of Skyllis and his daughter. The statue of Hydna completed the number of the statues that Nero carried off from Delphi. Only those of the female sex who are still pure virgins dive into the sea.

Herodotus (8.8) had mentioned a Greek deserter from the Persian side whom he called Skyllias, but not his daughter Hydna, or the portraits at Delphi; by the end of the fifth century Skyllias of Scione was evidently already the focus for tales of the sorts of amazing deeds that attracted Herodotus’ attention and that warranted singling him out in the text:

At this time in which they made a muster of the ships, there was in the [Persian] force Skyllias of Skione, the best diver of the men then living, who in the shipwreck that happened at Pelion saved much of the property on behalf of the Persians, but also got a lot himself. This Skyllias had it in mind even before to go over to the Greeks, but he did not have the means until that time. In what way he arrived among the Greeks I am not able to say exactly, and I am amazed if the things said are true: for it is said that having dived into the sea from Aphetai he didn’t come up for air until he arrived at Artemision, having traversed about eighty stades through the water. Even now many other implausible things are said about this man, but some true ones too; concerning this matter, my opinion is that he arrived by boat at Artemision. When he arrived, straightaway he detailed to the strategoi the shipwreck as it had happened, and told them about those of the ships sent around Euboia.

But even if the reasons for Herodotus’ interest seem clear, the justification for dedicating a portrait of Skyllias at Delphi is less so. If indeed Skyllias’ and Hydna’s portraits were set up soon after 480, they would be the earliest dedication in the sanctuary by the Amphictyony, predating by two hundred years the series of Hellenistic and Roman portraits the Amphictyons are known to have dedicated at Delphi: their only other offerings in the Classical period were statues of Apollo.46 As a familial portrait pair, Skyllias and Hydna would also have been exceptional in the fifth century. For these reasons alone, it would make more sense to suppose that the Delphic Amphictyony chose to commemorate Skyllias and Hydna’s exploits at Cape Artemision with portrait statues in the second half of the fourth century, when they also took the initiative to set up honorific portraits of contemporary subjects.

From Pausanias’ description, the portraits of Skyllias and his daughter stood in the midst of the Persian War monuments grouped just east of the temple of Apollo, near the colossal Salamis Apollo [Figure 26]. It is worth speculating about when and why the Delphic Amphictyony might have been interested in adding portraits commemorating an episode in Herodotus’ Histories to this array. I propose that the fact that Skyllias’ exploit had taken place off the coast of Thessaly was decisive. After putting an end to the Third Sacred War in 346 bc, Philip II effectively took control of Thessaly by reviving the traditional political institution of the tetrarchy and styling himself archon of all Thessaly. Philip could thus count on using Thessaly’s block of four votes on the Amphictyonic Council as justification to intervene in the Amphictyony’s internal disputes, as exemplified by the Fourth Sacred War of 340 bc. Soon after this, Philip’s Thessalian ally Daochos of Pharsalos dedicated his familial portrait group just north of the temple terrace. Like the Daochos group, the portraits of Skyllias and Hydna can also be interpreted as a piece of pro-Thessalian historical revisionism. Herodotus’ story of Skyllias seemed to show that the Thessalians and the other central Greek powers who controlled the Amphictyony at the very outset of the Hellenistic period, despite the general medizing and absenteeism which Herodotus attributed to them, really had done something to help defeat the Persians between Thermopylai and Salamis. Legitimizing the new political order brought in by Philip thus involved promoting a relatively insignificant story in Herodotus’ Histories and using it to deflect attention away from the general tenor of the narrative. By inserting Skyllias and Hydna into the commemorative space in front of the temple at Delphi, the Amphictyons claimed a larger place for themselves among the Greeks responsible for the Persian War victories.

Arimnestos of Plataia

The portrait statue of Arimnestos, the general who had commanded the Plataian contingent at both Marathon in 490 and Plataia in 479 bc, which Pausanias (9.4.1–2) saw standing next to Pheidias’ cult statue inside the temple of Athena Areia at Plataia, could potentially date within thirty years of the battle, but I would argue that circumstantial evidence favors a fourth-century date. Pheidias’ authorship dates the cult statue of Athena (and the temple within which it stood) to the 460s or the 450s at the earliest.47 The portrait’s placement alongside an important divine image finds possible parallels as early as the second half of the fifth century, when Themistokles’ sons supposedly placed a painted portrait of him within the cella of the Parthenon, and when Pausanias claims that a portrait statue of Alcibiades was placed beside the cult statue of Hera inside the temple in the Samian Heraion (Paus. 6.3.15, 410 bc).48 The vast majority of the evidence for this type of display, however, dates to the mid-fourth century and later.49

Simonides’ long elegy on the battle of Plataia compares the Greeks who died there to the heroes of the Trojan War, and they may have received immediate hero cult. The earliest description of the ceremonies performed at the tombs of the dead of Plataia appears in the account of Thucydides (3.58.4), writing after the destruction of Plataia by the Spartans in 427 bc. Thucydides, however, does not mention the panhellenic Eleutheria festival (the “Freedom Games”) held at Plataia.50 Roland Étienne and Marcel Pierart have argued that the games and the panhellenic koinon (council) that managed them were created only after the destruction of Thebes and the restoration of Plataia once again by Alexander in 335 bc. In the third century, the Eleutheria assumed added importance for the Greek city-states as they became associated with the struggle against Macedonian rule.51

Significantly, Arimnestos himself does not appear at all in Herodotus’ account of Marathon (6.94–117); Herodotus mentioned him only in passing in his account of the battle at Plataia (9.72), where Arimnestos appears not as leader of the Plataian contingent, but as a seemingly random participant to whom Kallikrates, singled out by Herodotus as the most handsome of the Greeks present at the battle, uttered his last words before he died:

These were the most noteworthy men at Plataia, for Kallikrates died outside the battle, he being the most beautiful of the Greeks to take part in the expedition, not only of the Lakedaimonians themselves but of the other Greeks as well. He is the one who, while Pausanias was performing the sphagia [pre-battle animal sacrifice], was wounded in the side by an arrow while sitting in his place. And while they were fighting, he was carried away and suffered badly; he said to the Plataian Arimnestos that dying on behalf of Hellas was not a sorrow for him, but rather that he did not use his arm, and that no deed worthy of himself had been accomplished despite his eagerness.

In sharp contrast, Plutarch (Arist. 11.2–7), making use of fourth-century or Hellenistic sources, tells the story that Arimnestos was visited in a dream by Zeus himself, who pointed him toward a proper site for the battle ultimately accepted by Aristeides, the Athenian commander:

To Pausanias and all the Hellenes under him Teisamenos the Elean made prophecy, and foretold victory for them if they acted on the defensive and did not advance to the attack. But Aristeides sent to Delphi and received from the god the response that the Athenians would be superior to their enemies if they … sustained the peril of battle on their own soil, in the plain of Eleusinian Demeter and Kore. When this oracle was reported to Aristeides, it perplexed him greatly. … At this time the strategos of the Plataians, Arimnestos, had a dream in which he thought he was accosted by Zeus Soter and asked what the Hellenes had decided to do, and replied: “Tomorrow, my Lord, we are going to lead our army back to Eleusis, and fight out our issue with the barbarians there, in accordance with the Pythian oracle”. Then the god said they were entirely in error, for the Pythian oracle’s places were there in the neighborhood of Plataia, and if they sought them they would surely find them. All this was made so vivid to Arimnestos that as soon as he awoke he summoned the oldest and most experienced of his fellow-citizens. By conference and investigation with these he discovered that near Hysiai, at the foot of Mount Kithairon, there was a very ancient temple bearing the names of Eleusinian Demeter and Kore. Straightaway he took Aristeides and led him to the spot … And besides, that the oracle might leave no rift in the hope of victory, the Plataians voted, on the motion of Arimnestos, to remove the boundaries of Plataia on the side toward Attica, and to give this territory to the Athenians, so they might contend in defence of Hellas on their own soil, in accordance with the oracle.

Though Plutarch cites no specific source for this story, it clearly echoes Herodotus’ (7.140–4) account of Themistokles’ role in the events leading up to the battle of Salamis: like Themistokles, Arimnestos resolves the problem posed by an ambiguous Delphic oracle given to the Athenians, and the solution involves the reinterpretation of a topographical reference.52 The Herodotean story about Themistokles could be the model for a later historical tradition about Arimnestos.

Both the portrait statue and the dream story greatly amplify the role played by Arimnestos and the Plataians, and one wonders whether Arimnestos’ portrait was set up in the later fourth century, when the Eleutheria (even if they had been founded already in the fifth century) became far more significant. The contrast between the meager role played by Arimnestos in Herodotus and Plutarch’s later treatment of him reinforces the supposition that Arimnestos’ portrait was retrospective: the portrait statue helps to fill a gap in Herodotus’ account of the battle of Plataia, and its placement at the foot of Pheidias’ colossal cult statue of Athena Areia seems to assert the primacy of the Plataians themselves in the events of 479 bc.

Portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles in Athens

A portrait of Miltiades was included in Pheidias’ large statue group at Delphi (Paus. 10.10.1), but we know of no contemporary, fifth-century portrait statues of Miltiades in Athens. He had been included as a recognizable participant, along with the polemarch Kallimachos and Aeschylus’ brother Kynegeiros, in the Marathon painting in the Stoa Poikile. In his speech of ca. 330 bc against Ktesiphon (Ctes. 186), Aeschines claimed that the Athenians had refused to allow Miltiades to inscribe his name on the painting. As Krumeich notes, the point here is surely that Miltiades and other fifth-century generals were not singled out individually in the dedicatory inscriptions on public monuments such as the Stoa Poikile and its paintings.53

Two other portraits of Miltiades in Athens known from literary sources paired him with Themistokles, a fact that in and of itself strongly suggests that the portraits were retrospective. A mid-second century ad scholion to Aristeides 3.154 (Dindorf pp. 535–6), contemporary with Pausanias, describes portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles in a group with two captured Persian prisoners somewhere in the Theater of Dionysos.54 Though victory monuments combining images of the victors with the vanquished go back at least as far as the Persianomachy dedicated by the Attalid kings of Pergamon on the Acropolis, dated by Andrew Stewart to ca. 200–197 bc, sculptures of fallen barbarians were typical of the Roman imperial period.55 The portraits of the Persian general Mardonios, Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus, and other Persian War figures seen by Pausanias in the Persian Stoa in the agora of Sparta (Paus. 3.11.3; Vitruvius 1.1.6) could date to a remodeling of the building in the Augustan period.56 An earlier, but still retrospective, pairing of portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles was to be found in the Athenian Prytaneion, located somewhere north of the Acropolis. This is one of very few instances in which Pausanias explicitly calls attention to the reinscription of earlier portraits with the names of new subjects: “They [the Athenians] reinscribed the portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles for a Thracian and a Roman, respectively” (Paus. 1.18.3). Though Pausanias mentions the fact of reinscription, he withholds the names of the new subjects for whom the portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles were reinscribed as a show of disapproval. In a brilliant hypothesis that still stands, Louis Robert suggested the Thracian king Rhoimetalkes III (eponymous archon of Athens in ad 36/7 or 37/8) and Gaius Julius Nicanor, an Augustan-period benefactor of the Athenians from Hierapolis in Syria hailed as the “new Themistokles” in inscriptions found in Athens.57 For our purposes in this chapter, the more important question is the portraits’ original date of manufacture. The portraits in the Prytaneion other than those of Miltiades and Themistokles all seem to date to the fourth or early third century; it is unlikely that the portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles in the Prytaneion date earlier than this. Zanker and others have connected the Prytaneion portrait of Miltiades and a Roman marble herm portrait in Ravenna, which depicts Miltiades not as a helmeted strategos, but wearing the himation of the good citizen.58 The portraits of Miltiades and Themistokles may either have been manufactured at the same time as a pair or brought together in the Prytaneion at a late date.59

Themistokles’ Portrait in the Sanctuary of Artemis Aristoboule in Athens

I have already discussed the portrait herm of Themistokles from Ostia [Figure 2]. The Ostia Themistokles exemplifies the tyranny of the Roman marble copy: once we have it, we must look for a fifth-century original to explain its existence. The date of ca. 480–470 bc that most scholars assign to the lost bronze original behind the Ostia herm further narrows the field of inquiry. The portrait most often associated with the Ostia herm is one described by Plutarch in his life of Themistokles inside the temple of Artemis Aristoboule in Athens. One serious objection to identifying the Ostia herm as a copy of a portrait that Themistokles himself dedicated in Athens is that it lacks a helmet: Plutarch’s description of the portrait in the temple of Artemis Aristoboule as “heroic” in appearance may imply a representation of Themistokles as a helmeted warrior, depicted “nude with weapons,” either standing at rest or in an action pose.60 This small sanctuary was discovered and excavated in the early 1960s [Figure 50], and no trace of either a portrait statue of Themistokles or the inscription for such a portrait was found.61 As the archaeological remains make clear, though cult activity began on the site soon after 480 bc, the temple itself was destroyed and lay in ruins until it was rebuilt in ca. 330 on the private initiative of Neoptolemos of Melite, a political associate of Lycurgus.62 The destruction and subsequent rebuilding of the Artemis Aristoboule temple make it unlikely that the eikonion of Themistokles that stood inside the building in Plutarch’s time was a contemporary, fifth-century portrait. In truth, though the eikonion of Themistokles has usually been assumed to be a small statue, the diminutive is uncommon and could signify a painted portrait, something like the painting of Themistokles dedicated in the Parthenon by his sons after his death in ca. 459 (Paus. 1.1.2).63 A retrospective portrait of the Lycurgan period, whether statue or painting, would be perfectly at home in the sanctuary as a dedication by Neoptolemos or the demesmen of Melite, a reminder of the sanctuary’s founder. As a later dedication in the sanctuary by an Athenian archon of 290/89 bc (IG II2 4658 = SEG XLIX 190; cf. CEG 2 784) shows, in the early Hellenistic period the cult and temple of Artemis Aristoboule founded by Themistokles were strongly associated with the fifth-century glory days of the Athenian democracy as the Athenians struggled to shake off Macedonian rule.64

But apart from the portrait of Themistokles in the sanctuary of Artemis Aristoboule, there are other possible contemporary portraits of Themistokles in Athens.65 The evidence that Themistokles himself founded at least one other sanctuary before his exile from Athens is indirect, but suggestive. Konon, who after his naval victory in 394 bc seems to have imitated Themistokles’ example, founded a sanctuary of Aphrodite Euploia in the Piraeus (Paus. 1.1.3).66 A fragmentary Athenian inscription of the Augustan period (IG II2 1035, line 45), listing up to eighty sanctuaries restored by the Athenians, includes one for a goddess (Artemis or Athena?) in the Piraeus founded by Themistokles before the battle of Salamis.67 Themistokles may have dedicated a portrait of himself in return for having been saved by the gods, either in an established sanctuary or one he had founded himself.

The portrait statue of Themistokles that stood in the agora of Magnesia on the Maeander in Asia Minor, where he was installed as governor by the Persian king Artaxerxes in 464 and where he remained until his death in 459 bc, is represented on a series of Magnesian coins of the Antonine period, one of them illustrated in the Introduction [Figure 4]. Thucydides (1.138) refers to a memorial (μνημεῖον) for Themistokles at Magnesia, but not specifically to a portrait; other sources (Diod. Sic. 11.58 and Plut. Them. 32.3) call this Themistokles’ grave, though it was widely believed after the fifth century that Themistokles’ sons had secretly transferred his remains to the Piraeus for burial (Plut. Them. 32.4; Ael. NA 6.15 = 569b). Only the Roman historian Cornelius Nepos (Them. 10.3) mentions a statue. But already in the fifth century, Aristophanes (Eq. line 83: 424 bc) had referred to the death of Themistokles by drinking bull’s blood, a story repeated by the sources of the Roman imperial period. This story may in fact have been inspired by the unusual iconography of the Magnesia portrait, which showed Themistokles sacrificing a bull: if so, then the statue must date to the fifth century and be identical with the memorial mentioned by Thucydides.68 The Magnesia portrait represented Themistokles as oikist and cultic hero, and its appearance (with long hair) seems to disqualify it as the original behind the Ostia herm.

The Themistokles Decree and the Athenian Women and Children at Troizen

A group of supposed Persian War portraits in Troizen in the eastern Argolid has attracted far less attention than the Ostia portrait herm of Themistokles, but they are worth discussing in relation to the Themistokles decree (ML 23), a retrospective document that constitutes one of the most important epigraphical discoveries of the twentieth century. Found near the agora of ancient Troizen and published by Michael Jameson in 1960, the Themistokles decree purports to be a decree passed by the Athenian Boule and Ekklesia, proposed by Themistokles himself, concerning the Athenian preparations to fight the Persians by sea in 480 bc.69 It has always been clear, however, that the inscribed stele itself dates to the early Hellenistic period. Though Jameson initially favored a connection with the Lamian War of 323–322 bc, the current scholarly consensus places the stele as late as the mid-third century bc.70 Habicht grouped the decree together with other Athenian retrospective documents that make their first appearance in Athenian oratory of the 340s bc.71

The most important element of the Themistokles decree for our purposes is the decision to evacuate women and children from Athens to Troizen (lines 6–8), a provision that seems to explain why the Troizenians of the early Hellenistic period displayed the decree in the first place:

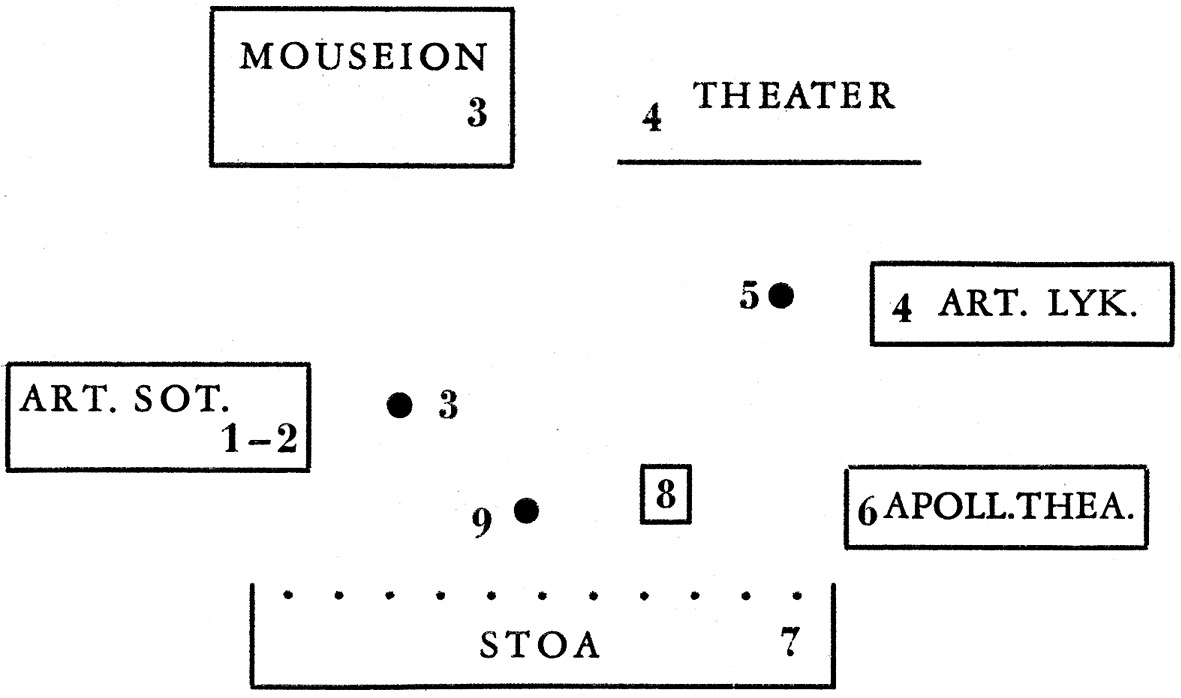

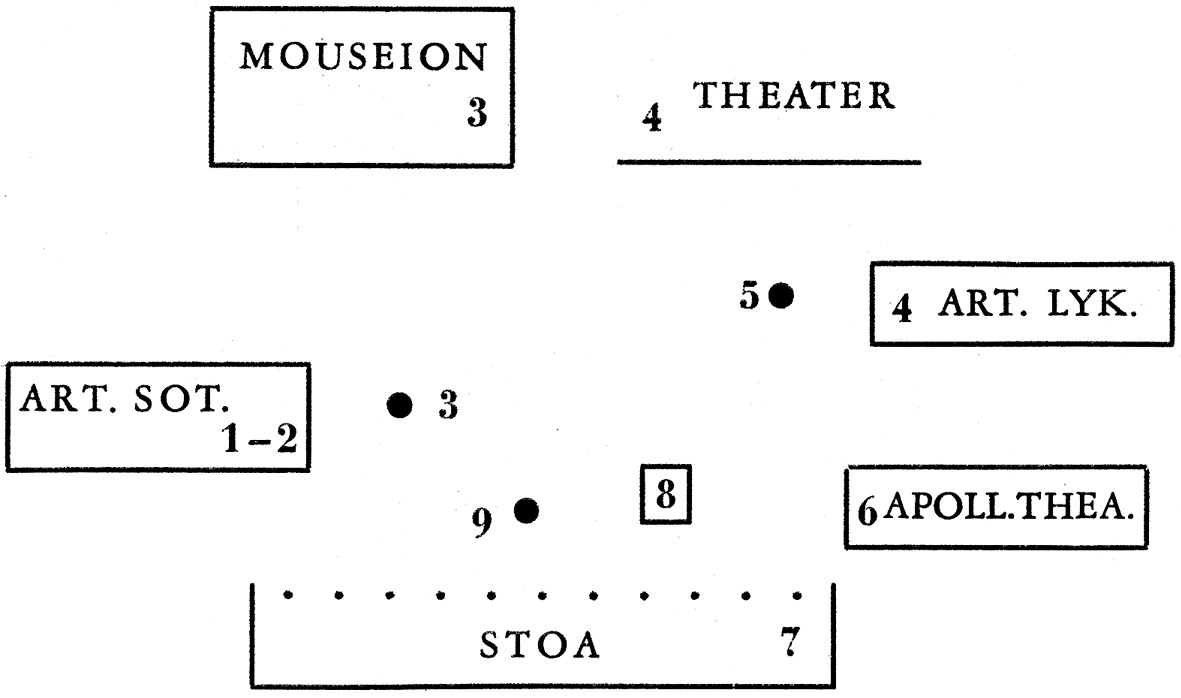

The Themistokles decree was reportedly discovered near the church of Hagia Sotira, built just north of the remains of the ancient agora of Troizen, which has only been partially excavated.73 Gabriel Welter, writing before the decree’s publication, used Pausanias’ account (2.31.1–8) to reconstruct the northern end of the agora of Troizen, the part closest to the later church of Hagia Sotira where the stele was found [Figure 52]. Here Pausanias mentions sanctuaries of both Artemis Soteira and Apollo Thearios; other inscribed decrees found in Troizen (e.g. IG IV 755, third century bc) specify that they were to be set up in the latter.74 Inside a stoa that Welter reconstructed as marking out the boundary of the agora, between the temple of Artemis Soteira and the temple of Apollo Thearios, Pausanias reported seeing the following:

There stand in a stoa in the agora women; both they and the children are made of stone. These are the women and children whom the Athenians gave to the Troizenians for safekeeping, when they chose to leave behind the city and not to await the Persian invader with infantry. They are said to have dedicated portraits not of all the women – for indeed there are not many – but only of those women who were of high rank.

52. Reconstruction of the agora of Troizen as described by Pausanias. The possible location for the statues of women and children mentioned by Pausanias is the stoa marked 7.

Neither the statues described by Pausanias nor inscribed bases for them were found in the German excavations of the site in the early twentieth century. Though some scholars have taken these statues at face value as contemporary portraits of Athenian women and children dating soon after 480 bc, others have wondered whether they might be retrospective portraits contemporary with, and displayed in connection with, the Themistokles decree.75 Two factors strongly suggest that this group of portraits dates later than the fifth century. The use of marble for portrait statues, though attested in the fourth century, became more common in the Hellenistic period, when we find rows of marble portraits standing both inside buildings and outdoors in Greek sanctuaries and agoras.76 Second, with a few notable exceptions, including boy victors in the Olympic games and the chorus boys of Sicilian Messene at Olympia, portraits of children are not attested until the end of the fifth century. After the Geneleos group of the mid-sixth century, statues representing children on their own or with their parents reappear in the fourth century in the Asklepieion at Epidauros. The row of marble portraits of women and children Pausanias describes simply finds no parallel in the fifth century bc.

I see two distinct possibilities for interpreting the portraits of women and children at Troizen. The first is that these were retrospective portraits, set up in the early Hellenistic period as adjuncts, and reinforcers, of the Themistokles decree displayed somewhere nearby. In this scenario, it remains an open question whether the Athenians themselves or the people of Troizen took the initiative and footed the bill for such an elaborate display.77 As we have seen, a possible parallel for this sort of mutually reinforcing combination of a retrospective inscribed document with a retrospective portrait statue is the portrait of Kallias displayed in the Athenian Agora with an inscribed copy of the peace of Kallias, both dating after the establishment of the cult of Peace in Athens.

The second possibility is that, whatever they were and whomever they in fact represented, Pausanias’ local guides at Troizen explained the statues of women and children inside the stoa in the agora at Troizen as monuments commemorating Troizen’s role in the Persian Wars. Pausanias’ lengthy account of Troizen (Paus. 2.30.5–32.10) was colored to an extraordinary extent by the oral testimony of local informants. The Troizenians of his own day, whom Pausanias characterizes as exulting in their own local history (σεμνύνοντες εἴπερ καὶ ἄλλοι τινὲς τὰ ἐγχώρια), attributed the foundation of not only their city, but also their cults, to legendary heroes. For example, according to Pausanias (2.31.1), they claimed that Theseus, the grandson of Pittheus the founder of Troizen, founded the cult of Artemis Soteira and gave her the epithet “Savior” after his slaying of the Minotaur and his subsequent return from Knossos. In addition to Pittheus and Theseus, Hippolytos, Herakles, Orestes, and Diomedes also figure prominently in the local traditions of Troizen as recounted to Pausanias by his informants: they even identified a statue which Pausanias recognized as an Asklepios made by the fourth-century sculptor Timotheos, whose work is attested at nearby Epidauros, as a representation of Hippolytos (Paus. 2.32.4). The local historical perspective documented by Pausanias at Troizen strongly resembles the phenomenon of “national time” observed in modern Greece and elsewhere by present-day anthropologists: historical reconstructions driven by a sense of national identity begin with the distant past and end with recent events, completely eliding the centuries in between.78

In light of the Troizenians’ tendentious interpretations of their own history, it seems possible that a group of Hellenistic marble portrait statues of women and children were retrojected by the Troizenians themselves back to the Persian Wars. The connection may have been encouraged by the statues’ location or proximity to the stele inscribed with the Themistokles decree; Pausanias himself may have believed that the statues were older than they really were. Welter suggested that the women and children in the agora of Troizen were in fact dedications to Artemis Soteira misidentified either by Pausanias or by his informants.79 Artemis Soteira, like Artemis Eileithyia and Artemis Brauronia elsewhere, may have been worshipped at Troizen as a savior of women in childbirth and their children. If this is the case, the portraits may belong to the later Hellenistic period, with no intrinsic connection to the Themistokles decree.

Maiandrios in the Samian Heraion: Remembering Samians and Forgetting Athenians

The portrait of Maiandrios in the Samian Heraion is the most certain example of a retrospective Persian War portrait; the evidence is epigraphical, and neither the portrait nor its subject are mentioned by any literary source. A fragmentary statue base found in the Heraion (IG XII 6 1 278: Figures 53 and 54) is inscribed with four partially preserved elegiac couplets, arranged in two pairs, naming and celebrating a Samian named Maiandrios, credited with capturing or sinking Persian ships at the battle of the Eurymedon:

II: [προὔμαχε τῶν Σαμίων] Μαιάνδριος, εὖτ’ ἐπὶ καλῶι| ἐστήσαντο μάχην Εὐρυμέδο[ντ-]

[παῖς? –. οὗτος ἀριστ]εύσας γὰρ ἐκείνηι| ναυμαχίηι πάντων κλέος ἔθετ’ ἀθάν̣[ατον.]

I: [δώδεκα νῆας ἕλεν Μαιάν]δ̣ριος, ὧν ἀπ’ ἑκάστης| ἀσπὶς πρύμναν ἔχει χείρ τ’ ὑποδεξ[αμένη.]

[τὰς δὲ βαθὺς τηλεκλε]ιτὰς ὑπεδέξατο πόντος| κρυφθείσας Μήδων συμμαχ̣[ίδας ψαμάθωι].

II. [ – ] Maiandrios, when [the Samians] offered battle at the fine Eurymedon [ – ]

[ – ] having distinguished himself in that naval battle, established undying honor.

I. Maiandrios [took – ships], of which from each one his shield keeps the stern, and his hand displays…

[ – ] the sea received the allies of the Medes [ – ].

In about 466 bc, the Athenian Kimon had led an Athenian naval contingent down the coast of Asia Minor; when they got to the mouth of the Eurymedon river in Pamphylia, the Athenians and their allies – none of the historical sources mentions any Samians among them – fought on both land and sea against an unprepared Persian force (Thuc. 1.100.1; Diod. Sic. 11.61–2; Plut. Cim. 12–13).80 Afterwards, Kimon pursued and routed the Phoenician ships coming to reinforce the Persians, and the Athenians commemorated their victories at the Eurymedon by dedicating a golden Palladion standing atop a bronze palm tree at Delphi (Paus. 10.15.4–5; Plut. Nic. 13.3; Plut. De Pyth. or. 8.397–8).81

When taken together, several features of the Samian monument make it clear that the portrait of Maiandrios is retrospective. First of all, the lettering of the epigrams places them in ca. 300 bc or slightly later, contemporary with the honorific decrees and portraits that followed the restoration of Samian self-rule in 321. Second, the remains of an earlier inscription show that the extant base block is reused, and that this block was originally inscribed in the first half of the fifth century bc with a list (IG XII 6 1 277) of the names and patronymics of a group of Samian men. The block upon which these names were inscribed in the fifth century was flipped on its side, with the result that the original name list appears – with no attempt at erasure – on the top surface of the block. If an original fifth-century portrait statue of Maiandrios were simply restored or reset on its base in the early Hellenistic period, as both Gauer and Dunst suggested, we would not expect a fifth-century inscription to be treated in this fashion.82 The reuse of material evidence from the period of the Persian Wars in a retrospective Persian War monument authenticates the Samian contribution in a way that an entirely new monument would not have done. I am therefore inclined to believe that the earlier inscription was intentionally preserved and respected by its reuse. A complicating factor is the impossibility of reconstructing the base as a whole from the small fragment that survives. There are no dowels for the feet of Maiandrios’ portrait, and it could be that this fragment served as part of a complex base composed of multiple blocks.

To explain the reuse of an earlier monument to support Maiandrios’ portrait, I find the following sequence of events most convincing. The fifth-century name list may in fact be a catalogue of Samians who distinguished themselves at either Mykale in 479 or the Eurymedon in ca. 466 bc, the only two engagements of the Persian Wars in which the Samians took part on the Greek side. Since a Samian naval contingent had fought on the Persian side at Salamis in 480, a public monument commemorating Samian participation on the Greek side at Mykale two years later would have helped to obliterate the memory of the Samians’ earlier medizing. Or, if the catalogue lists individuals connected with the battle of the Eurymedon, then it may even have included the name of Maiandrios, in which case the block’s later reuse in a retrospective monument to the Eurymedon becomes even more significant. The block inscribed with this list of names may have been damaged at some point between the 460s and ca. 300 bc. In ca. 300 or soon after, the restored Samian government decided to commemorate the Samian contribution against the Persians at the Eurymedon with a portrait of Maiandrios, an individual remembered as a hero of the battle for his capture or destruction of Persian ships.83 Klaus Hallof suggests that when the monument to Maiandrios was initially set up, only one pair of elegiac couplets – the pair lower down on the inscribed front face of the block – was included. These verses seem to tell the viewer that Maiandrios’ portrait held a shield which had on it prumnai, the curving sterns of a trireme also called aphlasta, equal to the number of ships captured or destroyed in the naval battle, and that Maiandrios held another of these in his hand. The lost statue’s iconography thus parallels that of one of the collective Persian War monuments set up by the Greeks soon after 479 bc, namely the colossal bronze Salamis Apollo at Delphi: according to Herodotus 8.121, this Apollo held the akrothinion or prow of a trireme in its hand. Soon after Maiandrios’ portrait was set up, a second pair of elegiac couplets praising Maiandrios was inscribed by the same hand just above the first pair.

Already in the fifth century, the Samians had attempted to reshape the memory of their ambiguous role in the Persian Wars through public monuments. Herodotus (6.14) mentions a column in the agora of Samos town inscribed with the names of the captains of eleven Samian triremes who fought against the Persian fleet at the battle of Lade during the Ionian revolt of 494 bc. This monument must date after the Samians had collectively switched to the Greek side at Mykale in 479.84 An incident narrated elsewhere by Herodotus opens up the possibility of yet another Samian public monument listing the names of the few Samians who had opposed the Persians from the beginning. According to Herodotus (9.89), three Samian aristocrats made a private embassy to the Spartan king Leotychidas on Delos urging him to liberate Ionia, which Herodotus claims was the impetus behind the Mykale campaign of 479 bc. Herodotus’ knowledge of both the names and patronymics of these Samians suggests that he saw them inscribed on a monument on Samos, possibly also in the agora.85 Finally, on the temple terrace at Delphi, where the Greeks collectively had dedicated the colossal bronze Apollo to commemorate the victory at Salamis [Figure 26], the Samians dedicated their own lifesize bronze Apollo (FdD III 4 455) inscribed simply Σάμιοι/τὠπόλλονι (The Samians [dedicated] to Apollo).86 The form and location of the monument encouraged an association with the entire campaign against the Persians, which the Samians were late to join.

The retrospective portrait of the fifth-century naval commander Maiandrios, shown armed with a shield and holding the aphlaston of a captured ship, would have resonated with both contemporary portrait practices and with its setting in the Samian Heraion.87 The fifth-century portrait of the Samian Hegesagoras, discussed in Chapter 3, commemorated the same series of events and might still have been standing in the sanctuary. By suddenly remembering Maiandrios, the Samians were in effect forgetting Kimon and the Athenians, while converting the late and ambiguous Samian role in the Greek victory over the Persians into a major contribution. We can find no clearer illustration of the portrait culture of the late fourth century than the redeployment of a fifth-century monument 150 years later as the base for a retrospective portrait that focalizes memory of the naval battle of the Eurymedon in the person of an individual.

Conclusion

Retrospective portrait monuments constituted an important part of the production of Greek portraits in the fifth and fourth centuries bc. The Greeks’ versions of their own Archaic and Classical history were shaped by such portraits, as surely as the statues of Harmodios and Aristogeiton in the Athenian Agora shaped Athenian memory of the beginnings of the democracy. Some individuals were remembered with portraits to help forget others. Some of the portraits examined in this chapter speak to a desire to leave markers where important historical events had taken place. Some served as reminders of literary figures and their works, laying claims to the memory of authors such as Anacreon of Teos by their locations. Retrospective portraits of Miltiades, Themistokles, and other subjects aimed to fill perceived gaps in the historical memory of the Persian Wars of 490–479 bc. They either reinforced the authority of written documents, both historiographic narratives and documents inscribed on stone, or challenged them by promoting the memory of individuals passed over in canonical fifth-century texts such as Herodotus’ Histories. Placing a retrospective portrait in a particular location often furthered local interests. Though this chapter has focused on the phenomena of cultural retrospection and memory in fourth-century Greece, the story does not end there. Throughout the Hellenistic and Roman imperial periods, the production of portraits representing the Greeks of the Archaic and Classical periods continued; so did the reuse and reinterpretation of portraits from the Greek past.