Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

8 - TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 September 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

Summary

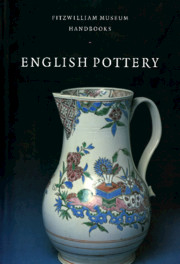

Tin-glazed earthenware painted in high-temperature colours; initialled and dated ‘W/WS 16:61’. Height 7.7 cm, diameter 48.5 cm. C.1426–1928.

Large delftware dishes, known today as chargers, were made between about 1600 and 1740. Most of them are decorated with variants of a few simple themes: geometrical patterns, fruit and foliage, tulips and other flowers arranged in a vase or growing from a mound, Adam and Eve with the Tree of Knowledge, and portraits of monarchs or other persons. Less common subjects include biblical scenes, the royal yacht, windmills, and unicorns. The rims are usually encircled by slanting blue dashes, hence the term ‘blue dash chargers’ coined by the Rev. E.A. Downman, who published a book with that titlein 1919.

Tulip mania developed in Holland during the 1620s and 1630s and spread from there to England and other Western European countries. After the Restoration in 1660, Dutch influence on the arts in England was very strong and for about thirty years floral decoration of all kinds, including cut flowers in vases, was extremely fashionable. Tulip chargers were an expression of this love of flowers. This is the earliest dated example with a blue dash edge but they were probably made from the late 1650s. Unlike most chargers which have curved sides, it has a shallow well and a broad rim decorated with pomegranates and parti-coloured leaves. These originated on the Continent but their arrangement in panels alternating with panels of trellis pattern suggests that the decorator was influenced by the borders of Chinese blue and white porcelain dishes of the Wanli period (1573–1619).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- English Pottery , pp. 26 - 27Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1995