Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface: A Theory of Justice?

- 1 Introductory Themes: Images of Evenness

- 2 The Talion

- 3 The Talionic Mint: Funny Money

- 4 The Proper Price of Property in an Eye

- 5 Teaching a Lesson: Pain and Poetic Justice

- 6 A Pound of Flesh

- 7 Remember Me: Mnemonics, Debts (of Blood), and the Making of the Person

- 8 Dismemberment and Price Lists

- 9 Of Hands, Hospitality, Personal Space, and Holiness

- 10 Satisfaction Not Guaranteed

- 11 Comparing Values and the Ranking Game

- 12 Filthy Lucre and Holy Dollars

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

8 - Dismemberment and Price Lists

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 December 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface: A Theory of Justice?

- 1 Introductory Themes: Images of Evenness

- 2 The Talion

- 3 The Talionic Mint: Funny Money

- 4 The Proper Price of Property in an Eye

- 5 Teaching a Lesson: Pain and Poetic Justice

- 6 A Pound of Flesh

- 7 Remember Me: Mnemonics, Debts (of Blood), and the Making of the Person

- 8 Dismemberment and Price Lists

- 9 Of Hands, Hospitality, Personal Space, and Holiness

- 10 Satisfaction Not Guaranteed

- 11 Comparing Values and the Ranking Game

- 12 Filthy Lucre and Holy Dollars

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

We cannot leave wergeld just yet. First read this law from England, c. 1015 a.d.:

The oath of a twelve-hundred man is worth the oaths of 6 ceorls (churls); therefore, if a person needs to avenge a twelve-hundred man he will be fully avenged by killing six ceorls and his wergeld is the wergeld of six ceorls.

Funny that the text does not just say that the wergeld of a churl is 200 shillings or that the wergeld of a 1200 man is 1200 shillings. Instead it chooses to value the 1200 man in terms of churls and vice versa, while the shillings remain unexpressed. When we say that something will cost you a cool million, we know that “million” means a million dollars. And I suspect they knew that the bare number 1200 meant 1200 shillings, but then what do we make of this text contemporaneous with the one just quoted? “The wergeld of a twelve-hundred man is twelve-hundred shillings. The wer of a two hundred man is two hundred shillings.”

Why must the obvious be hammered home so, unless it is no longer obvious? Had the number-based status terms become something of a dead metaphor so that they needed to be enlivened by reminding what the numbers stood for? Maybe people were settling for what they could get – settling for, say, 70 percent on the shilling – and this was deemed a sign of a general decay of order and values, and the provision was meant to assert the nonnegotiability of the price.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

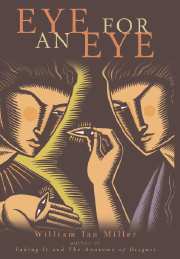

- Eye for an Eye , pp. 109 - 129Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005