As the British and Commonwealth Armies in Italy, Burma and the South-West Pacific gradually wore the German and Imperial Japanese Armies down in battle, planning for the ‘second front’, the ‘great crusade’ in North-West Europe, gathered pace. By the second major Anglo-American conference, held in Casablanca in January 1943, it had become clear that the proposed invasion would not commence before 1944; the British timetable for the war against Germany had won out. Planning for the cross-Channel invasion, however, could not wait until 1944;1 there had to be an individual and an organisation in charge of preparations who ‘would impart a dynamic impetus’ to preparing what was envisaged to be the decisive campaign of the war.2 In April 1943, Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan, the commander of British I Corps in the United Kingdom, was appointed to this role as Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (Designate); the Supreme Allied Commander had not yet been appointed. Morgan rapidly put together a new organisation, which was to become known as COSSAC (derived from the first letters of his title) and began detailed planning for the invasion of North-West Europe, now codenamed ‘Overlord’. By the end of July, Morgan and his staff had prepared a plan for a cross-Channel invasion in May 1944 and specifically for an assault on the beaches of Normandy on the north-west coast of France; it won approval from Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff and was presented to the Americans at the Quebec ‘Quadrant’ conference in August 1943. There, Roosevelt and the US Chiefs signed it off.3

At last, the Allies had the beginnings of a concrete plan for the final defeat of the Wehrmacht on the Continent. The choice of commander for the forthcoming invasion, however, was no easy task. The two most senior officers in the British and US armies, Brooke and Marshall, harboured ambitions to return to the field, but both men were indispensable in their respective roles in London and Washington. In the circumstances, it was decided to move the experienced, and thus far successful, leadership team from the Mediterranean to London to take over the planning and execution of the invasion; Eisenhower was announced as Supreme Allied Commander on 6 December 1943, with Tedder appointed as his deputy. On 24 December, Montgomery was informed that he would take charge of the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group and have overall command of the Allied land forces (until Eisenhower took over). General Omar Bradley would command 12th US Army Group and Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey, who had started the war as a battalion commander in France and who had risen through the ranks to command a corps in the latter stages of the campaign in North Africa and during the fighting in the Mediterranean, would command British Second Army. Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar would take charge of First Canadian Army once sufficient Canadian formations had landed in Europe. Beneath these men, the five Anglo-Canadian Army corps (I, VIII, XII, XXX and II Canadian) would be commanded by Lieutenant-General John Crocker, Lieutenant-General Richard O’Connor, who had escaped from Italian captivity and returned to the UK, Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie, once more given an operational command after the disaster at Gazala in 1942, Lieutenant-General Gerard Bucknall and Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, who had commanded 1st Canadian Division in the Mediterranean.4

It was the good fortune of these men that they took charge of armies that, in many ways, had been ‘rebuilt and reinvented’ since the disasters of the early years of the war. Nevertheless, the challenge ahead of them was immense. The British and Commonwealth Armies in the United Kingdom were, as they had been throughout the war, made up of citizen soldiers; around 75 per cent of troops were conscripts, the rest being professionals and volunteers.5 Some had experienced defeat in France and escaped from Dunkirk in June 1940. Others, such as the veteran 7th Armoured, 50th Northumbrian, 51st Highland and 1st Airborne Divisions, and 4th and 8th Armoured Brigades had fought for many years in the Middle East and Mediterranean theatres and had experienced both heady victories and devastating defeats. The rest, the majority, had experienced no combat at all and relied exclusively on training to prepare them for the challenges ahead;6 of the twenty-five divisions stationed in the British Isles on the eve of the invasion, only five (20 per cent) had seen service overseas since the outbreak of the war.7

Training and Doctrine

In these circumstances, the quality of training was key; the dramatic turnaround in the basic competence of the British and Commonwealth Armies in the Middle and Far East would have to be replicated in the United Kingdom. Indeed, it was; 21st Army Group, and Home Forces before it, pursued a very similar approach to that which had been successfully initiated in these other theatres. Even before the arrival of Montgomery and his team in the UK, a centrally controlled tactical training programme for new recruits, under the Director of Military Training at the War Office, had been introduced (in 1942).8 All new recruits in the Army were now enlisted into a General Service Corps, where ‘a common syllabus of six weeks primary training’ was carried out. During this period, selection tests were performed (see Chapter 7) ‘to determine the type of employment for which the recruit was most suited’.9 After the six-week primary training programme, and a week’s leave, men would then move to corps training centres for the arm with which they were to serve. Infantry were given the shortest period of specialist training, ten weeks, while signals were given the longest, up to thirty weeks. The men were then transferred to one of the new ‘reserve’ divisions (formed in late 1942), of which there were three for most of the war. Here, they were given five weeks additional ‘collective’ and ‘crew’ training before they were sent to their field formations. Gone were the days when each regiment was left to its own devices to train its recruits.10

To complement this rationalisation of the training of new recruits, a plethora of ‘schools’ and training establishments were set up, much as had been the case in Australia and India, to prepare the Field Army for the challenges that awaited. By October 1942, there were no fewer than thirty-two schools under the Director of Military Training, including an Armoured Fighting Vehicle School at Bovington, an Advanced Handling and Fieldcraft School at Llanberis, a Mountain and Snow Warfare Training Centre at Glenfeshire and a Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) Officers Tactical School at Tidworth. By the end of 1942, the School of Infantry had been founded at Barnard Castle in Northern Command, where the training of instructors and the development of doctrine was centralised and controlled.11

That is where the similarities between the reform of the Australian and Indian Armies and that of the British and Canadian Armies in the United Kingdom ceased. For, whereas new doctrine, as encapsulated in the ‘Jungle Soldier’s Handbook’ and the ‘Jungle Book’, had directed and animated the retraining of the armies in the East, the preparation of 21st Army Group was not guided by a similar and universally accepted evolution in doctrine. The key manual guiding the training of the British Army during this period, ‘Infantry Training’, had not been revised since 1937. A provisional document pending the long-awaited rewriting of ‘Infantry Training’, ‘The Instructor’s Handbook on Fieldcraft and Battle Drill’ (published in October 1942), focused almost entirely on battle drill as the ‘accepted’ and ‘orthodox way to teach tactics’.12 The problem was that many commanding officers were sceptical about the utility of battle drill as a catch-all solution for tactical problems on the battlefield. ‘The Instructor’s Handbook’ would, therefore, not play the role of the ‘Jungle Soldier’s Handbook’ or the ‘Jungle Book’ for 21st Army Group.

Some commanders were so concerned about the utility of battle drill that they were ‘reluctant’ to send their junior officers and NCOs to schools because they saw the teaching in such establishments as ‘not in accordance with what goes on in battle’. Many believed that Battle School trainees were ‘wooden’ in action, trying ‘to apply a manoeuvre which they have previously seen to totally unsuited situations and ground’.13 Moreover, when push came to shove, too many commanders had ‘fundamental doubts’ over the ‘moral fitness of the typical infantryman’ to apply ‘battle drill to common tactical ends’. The adoption of such approaches required devolving, to the lowest levels of the army, decision-making, about, for example, when to go to ground and when to advance. Many held that ‘once down soldiers would refuse to get up again’, and that, therefore, it was far more effective to tell soldiers when to advance, to encourage them to keep their feet and rush forward by ‘leaning’ on a barrage.14

The influence of the great defeats of 1940 to 1942 was hard to shake. Crerar, the commander of First Canadian Army, wrote to his men in May 1944, that the ‘temptation to “go to ground”’ must be resisted and that this had to be ‘thoroughly drilled into the minds of all those under command’. Those troops that allowed themselves to go to ground were ‘doing exactly what the enemy wants’:

The longer they remain static, the more certain it is they lose the assistance of their own supporting fire programme, and that they will become casualties to the defensive fire of the enemy. To press on is not only tactically sound, it is, for the individual, much safer.15

The revised Infantry Training Manual, which was, according to some historians, the ‘most important tactical manual to be issued by the British Army during the Second World War’, was released in March 1944, far too late to guide the training of those formations destined for Normandy.16

In the absence of a universally accepted doctrinal solution to the tactical problem, such as that disseminated in the East, Montgomery had scope to take a grip of 21st Army Group and direct training as he saw fit. Indeed, it is apparent that Montgomery’s thinking about his operational approach had evolved since his days in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. In light of the attritional battles of 1942 and 1943 and the fact that he was commander of an army group rather than an army, he recognised that he had to rebalance the relationship between control and initiative in his armies. Up to El Alamein, he had been adamant that the commander who was ‘fighting the battle’ had ‘to be able to exercise full control and give quick decisions in sufficient time to influence the fast moving tactical battle’.17 By 1944, he was stressing a very different ethos, one that began to resonate more with interwar FSR than with ‘Colossal Cracks’. ‘Within the general limits’ of his ‘framework’ or his ‘instructions or plan’, he told his generals, ‘subordinates do as they like’. It was ‘essential’ for his subordinates ‘to establish confidence’ and ‘accept responsibility and get on with the job’. Armies, corps and divisions would ‘run their own show’, once they had received ‘the general form from me’.18 ‘Rather than telling people how to do things’, Montgomery now ‘insisted on the importance of people coming up with their own answers with regard to tactical problem solving’.19 In Normandy, he would seek a ‘more rapid tempo in sequencing between phases and operations’ in response to the ‘tactical and operational problems’ he expected to face.20

The shift in focus illustrated Montgomery’s capacity for reflection and the continuing influence of interwar FSR on the thinking of senior British commanders. Before 1939, when commander of 9th Infantry Brigade, he had written that:

We must remember that if we do not trust our subordinates we will never train them. But if they know they are trusted and that they will be judged on results, the effect will be electrical. The fussy commander, who is for ever interfering in the province of his subordinates, will never train others in the art of command.21

Montgomery’s imposition of a centralised rather than directive command and control system on Eighth Army had not been the result of pre-war doctrine, or the influence of the First World War; it evolved instead from his experience of the first years of the Second World War. In the circumstances, in the specific context faced by Eighth Army, he had acted pragmatically and found a way to win. Now, having been thoroughly frustrated by his experience in the Mediterranean, he once more sought to adapt his approach.22

The fact that he largely failed in this endeavour has much to do with training. Before Montgomery’s arrival as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) in January 1944, ‘the object’ of collective training in the UK had ‘usually’ been ‘determined by G.H.Q.’.23 Sir Bernard Paget, the first commander of 21st Army Group, had no qualms about laying down ‘the pattern of training for all formations’.24 But, on taking over his new command, Montgomery explicitly forbade centrally mandated training guidelines. ‘I have no training instructions’, he told his generals on 13 January 1944, ‘Army Comds train their armies.’ ‘Good troops who are well officered, well trained, mentally alert, and who are fit and active’, he continued, ‘will adapt themselves to any conditions. Do not cramp initiative or break the chain of command, in the issue of training instructions.’ Army group Monthly Training Letters were ‘to be discontinued’ and ‘all orders’ contained in these letters ‘saying that unit commanders will do this, or that’, were to be ‘cancelled’.25

This was radically different to Montgomery’s approach to training for El Alamein when he had been more than happy to set out precisely what formations had to cover in training.26 In hindsight, the decision to leave the direction of training in the hands of subordinates seems perplexing, especially considering the lessons of the early years of the war. The outcome was that a rather dysfunctional hybrid doctrinal formula emerged in 21st Army Group. Senior officers, left to their own devices, ‘married’ two approaches, battle drill and mechanised firepower. Troops were trained to employ battle drill, but only when bombardments had failed to adequately open the way for the infantry to advance. Priority was unquestionably given to the mechanised firepower-heavy approach of advancing behind a barrage, as it had been proven to work.27

The ‘Colossal Cracks’ formula would, thus, be rolled out once again in Normandy. This method, as evidenced from experience in North Africa and the Mediterranean was attritional, ‘with the twin objectives of seizing ground and wearing down an enemy’. It was not elegant and it severely limited the possibilities for exploitation, but to most ‘there were few better realistic options available’. Although often costly in terms of lives and resources, these tactics were ‘likely to inflict serious damage’ on a defender ‘who was doctrinally committed to counterattacking for every lost yard of ground’. The strength of ‘Colossal Cracks’, therefore, ‘lay in that it switched the combatants’ places, so that the attacker, upon reaching the objective, could dig in and assume a defensive stance, with most of the advantages of the defence on their side if they could entrench themselves rapidly’.28

In spite of the doctrinal ‘fluidity’ that overtook 21st Army Group in the run-up to the invasion of North-West Europe, there can be little doubt that Montgomery’s armies did train with great energy and focus. The exercises undertaken by 21st Army Group prior to D-Day ‘represented probably the most extensive and thorough training programme the British army in the UK had ever undertaken’.29 The censorship summaries for North-West Europe support this assessment. The reports for April and May 1944 were based on 127,797 British and 32,163 Canadian letters and each bi-weekly report had a section devoted to training. From these, it is clear that, in many respects, no military formation ever went into battle more thoroughly prepared. They note ‘many references to tough training and strenuous field exercises’. By April 1944, training had ‘reached a high level’; it was ‘invariably enjoyed’; and the ‘personal fitness’ of the troops was of a high standard. The ‘general picture’, according to the summaries, was one of ‘efficiently run units with discipline at a high level’.30 By the start of May, the censors noted that ‘strenuous and organised training schemes have contributed greatly to the confidence, and general sense of physical and mental well being of the troops’. A private in the 2nd Gordon Highlanders,31 of 15th Scottish Division, a territorial division that had spent the war training in Britain, wrote, ‘our training is simply terrific just now and we are seldom in the camp. We are certainly going through our paces these days, but it’s all for the best.’ A company sergeant major in the 1st King’s Own Scottish Borderers, 3rd Division, which, since its evacuation from Dunkirk, had also spent its time training in Britain, remarked that ‘things are going along well … I am feeling almost done up as we were out all night on a very hard bit of training and I reckon I must have been marched the whole length and breadth of dear old Britain.’32

Comments on being ‘trained and ready’ were ‘frequent’ in Canadian mail too, one man writing, ‘if we don’t know how to use our equipment or how to fight by now we never shall’.33 By the end of May, British troops were writing home to the effect that they were ‘like race horses waiting for the word “go”’. ‘The standard of training is high’, reported the censors, ‘and the large number of references are usually associated with expressions of fitness and readiness for action. Writers invariably refer to training as hard and arduous, but without complaint.’34 The Canadian censors noted that ‘the many references to training’ were ‘linked with expressions of confidence and fitness, and emphasise the morale and preparedness of the troops’.35

Such evidence is backed up and given colour by the secondary literature.36 The historian of one of the assault divisions, 3rd British Division, which had trained for over a year for its role in the invasion of the Continent, recalled that by the autumn of 1943, ‘every soldier knew what to do on coming to grips with the enemy on the occupied land of Europe’.37 Realistic training exercises (especially with regards to the initial beach assaults), battle schools and battle inoculation had taken their toll in casualties. However, as Lieutenant-Colonel Trevor Hart Dyke, of 49th West Riding Division, which had spent much of its time since Norway garrisoning Iceland and, from 1942, training in Britain, recorded, ‘this policy was well rewarded when we went into battle, as we were not then unduly perturbed by the noise and danger of war’.38 The 21st Army Group was trained and ready to go; time would tell whether the inconsistencies inherent in its doctrine and preparation for Normandy would play out detrimentally on the battlefield.

Selection and Morale

To support 21st Army Group’s training programme, a major effort was made to select the right men for the coming campaign and to get the most out of the human element of the combat problem. The years of defeat had been associated with an extremely inefficient use of the human resources available to the Army. The War Office was determined to ensure that the same mistakes were not made again. Between September 1943 and D-Day, an intensive programme of personnel selection and testing was carried out on the units of 21st Army Group. About 180 personnel selection officers (PSOs) and 200 sergeant-testers were employed and by D-Day the ‘great bulk of the troops in forward areas had been visited’ and assessed. The procedure was then extended to reinforcements, and, in the end, nearly all arms were covered.39 Once testing had been completed, ‘ratings conferences’ were held between PSOs and unit representatives to assess ‘each soldier’s’ general character and efficiency. All information gained was entered on men’s records and on their Field Conduct Sheets in the form of special Monomark codes which, when translated, gave the soldier’s physique, age-group, general intelligence and knowledge, standard of education, nature of present duties and suitability for training on other duties. Every CO had this information at his disposal and, as a result, was ‘better able to choose the “right man for the right job”’.40 Those officers, NCOs and men who were considered ‘unsuitable’ for the forthcoming campaign were reallocated and posted to activities more appropriate to their intellect and skills.41

In February 1944, a psychiatric advisor was attached to 21st Army Group and provision was made for medical officers specially trained in field psychiatry to be allocated to corps and higher formation staffs.42 One of these men, Major Robert J. Phillips, who joined VIII Corps in September 1943, recalled that he spent much of his time in the run up to D-Day lecturing and liaising with medical officers, regimental officers and padres on the problems of psychiatric casualties in battle. By March 1944, he was confident that all medical officers in the corps had ‘realised the importance of watching for incipient signs of early breakdown’ and ‘were showing a marked interest in and keenness to learn something of psychiatry’. Between October 1943 and May 1944, 770 men in VIII Corps were psychiatrically evaluated, the majority of whom were transferred, downgraded or discharged. Just before D-Day, Phillips distributed three pamphlets on battle exhaustion and organised a ‘Study Day’ for all corps medical officers. Additionally, in the final exercise before embarkation, Philips had VIII Corps practising the evacuation of ‘mock psychiatric battle casualties’.43

The Canadian Army was equally convinced of the value of weeding out unsuitable men prior to combat on the Continent. A neuropsychiatrist was attached to each of the divisions (2nd, 3rd and 4th Armoured) that were to take part in the campaign. These specialists carried out ‘psychiatric weeding’ and gave ‘instruction’ to medical officers on the handling of breakdown cases in battle. Such screening and teaching was particularly intensive in 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, which was to assault Juno beach on 6 June. Major R. A. Gregory, the Division Neuropsychiatrist, instructed all the medical officers, and they, in turn, gave an hour-long talk to officers of their units and another one to NCOs. In all, 127 men were removed on psychiatric grounds from this division in the three months running up to the landings.44 The other two divisions had less instruction and pre-invasion weeding.45 Nevertheless, between 8 May and 9 June 1944, a course of five lectures on army psychiatry was given to the medical officers of 4th Canadian Armoured Division and forty-one soldiers in the division were referred to psychiatrists, of whom only thirteen were returned to their units.46 Overall, across the Canadian Army in the UK, 5,813 men were assessed and downgraded in the six months before the invasion.47

Allied to the imperatives of training and manpower allocation, was the issue of morale. Indeed, morale received more attention and careful management in the period before D-Day than before any other operation of the Second World War. Over the many years of training and preparation in the UK, attempts had been made to foster a greater commitment to Britain’s war effort. Army education, in particular, had sought, through discussions and citizenship instruction, to excite troops about the possibilities of broadly defined social and political reforms in Britain. However, even these educational innovations, while heightening soldiers’ political awareness and increasing their understanding of the ideals of democracy, were not sufficient, in light of the Government’s unwillingness to promise real reform, to produce high and enduring morale and motivation.48

Matters were not improved when the much-anticipated news of increases in pay for British soldiers was announced in April 1944. The increment, in marked contrast to its reception in the Mediterranean, was widely judged as too small; the difference between military rates of pay and civilian wages was just that more apparent for those still serving on the home front. Of ten pages addressing morale in the censorship summary for Second British Army, 1 to 15 May 1944, three were dedicated to the subject. It reported that it was ‘generally expected’ that the increase in pay and allowances ‘would be substantial all round, and the disappointment has had a marked effect on the spirit of the troops … The increase of 3d a day is held up to ridicule by all.’49

The paltry improvement left many wondering about the extent to which they were valued by the state. Some wished that they were young enough to emigrate; others talked of ‘revolution’ and a concern for how they would be treated after the war. The company quarter master sergeant of 3rd Monmouthshire Regiment, 11th Armoured Division, remarked that ‘I’m afraid I cannot think anything about him [Churchill] after those scandalous pay “concessions” … What we want in the army is a first class trade Union now.’ As regards officers, ‘the general opinion’ was that unless they enjoyed a private income they could ‘barely manage’. A major in an unnamed British infantry brigade wrote:

I was also surprised about the recent ‘services pay increase’ – and it’s little short of scandalous … Have you ever heard of the miners or railwaymen striking and being appeased by an additional 7/6 a month … Either it shows up what our government thinks of ‘the officer’ – or as has always been the case he is expected to be a man of means. When will it be recognised that an officer can be a professional in his business, and make it a life study. No, seemingly it is still a hobby to be indulged in but his income must come from private sources … the cost of living is up by 40% – taxation has been doubled – both since 1938 – and still I could get no more pay than then … Every other person, not in the forces, is earning twice sometimes three times his pre-war wage.50

The War Office had neither the power nor authority to fully compensate for a government that at its heart eschewed the dramatic changes the soldiers craved. Thus, great efforts were made to manage those influences on morale that were in the Army’s control. The need for ‘spit and polish’ could not be completely done away with, but soldiers could be treated as valued and respected citizens and be led in humane and imaginative ways. A remarkably sophisticated system to monitor and manage morale in the lead-up to, and during, the North-West Europe campaign was developed through better officer selection and training and by utilising the intelligence gained from unit censorship.51

The use of censorship, in particular, allowed the Army to react with great speed to the needs of the men. Those in charge of unit and base censorship, on learning of some defect or problem, would write to officers in command of units and formations.52 These interventions would typically lead to concrete actions to address the men’s concerns. The Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) were able to confirm by the second half of 1943, for example, that ‘every individual case’ brought to their attention through the ‘extremely interesting and useful’ censorship reports, was addressed.53

Efforts were made to ensure that this important feedback loop would work on the Continent too. Whereas there had been delays in the arrival of censorship sections in previous campaigns, censorship units would now ‘proceed to the theatre of war in small parties attached proportionally to formations’ until a base censorship apparatus was fully up and running. This would both improve security and ensure that GHQ was provided with ‘useful up to date censorship morale reports’.54 Divisions, battalions, companies and platoons in need of cigarettes, clothing, better equipment, leadership, or rest, would be identified through censorship and action would be taken.

The ‘Montgomery effect’ was an important factor too; before D-Day, Montgomery took the time to address all the men in his huge command, formation by formation, to assure them that the invasion would succeed.55 In these speeches he emphasised again and again the vital importance of morale and the need for senior and junior officers to nurture it in their men at all available opportunities.56 The Army may have lacked one of the key ingredients of a highly cohesive organisation, a passionate commitment to a cause; nevertheless, it identified this deficit and proved adept at managing morale in other ways.

By the middle of April 1944, as 21st Army Group began to assemble in the south-east of England, it was clear that these efforts had largely paid off.57 The censorship summaries presented a picture of ‘keen, well trained troops’. Morale was described as ‘high’, and a ‘good fighting spirit’ was frequently noted in the mail.58 Phillips recalled that the VIII Corps’ move from its training area to the south of England had ‘produced an uplift in morale which was very evident’:

At last our troops felt that the time would not be long before they could put all their intensive training into actual practice. The vast mixture of Corps and Divisional signs that one saw in the South added to the spirit of comradeship and served to produce a realisation that one’s own Corps was not alone in the party to come.

Phillips had expected an increase in psychiatric cases due to ‘embarkation fever’ but was relieved to find that his fears were unfounded; he saw fewer cases per week than usual.59 A similar situation pertained in I Corps.60

While morale was clearly very good, the censorship summaries show what can only be described as a ‘growing tension’ as D-Day approached. Expressions of anxiety ‘to get on with the job’ and ‘to get it over’ and ‘get back home’ were present. Inter-Allied strains rather than co-operation were evident in the mail. Unfavourable comments about American troops outnumbered favourable ones by 2:1, while ‘isolated unfavourable comments’ with regards to Canadian troops were also noted. Many of these tensions were driven by inequalities in pay and welfare amenities. However, it was the American and Canadian troops’ relationships with British women that most upset the ordinary Tommy. A rifleman in the 2nd King’s Royal Rifle Corps, 4th Armoured Brigade, commented that there had been ‘3 cases of men’s wives leaving them for Yanks or Canadians in this [company] in the last two weeks. So do you wonder as why we can’t stand them.’ There was apparently ‘a lot of fighting going on at dances with the Canadians’. One local dancehall was, according to a driver in the Royal Army Supply Corps, nicknamed the ‘Bucket of Blood’ due to the constant ‘clashes between our boys and Canadians’.61 As a private in the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, 15th Scottish Division, put it, ‘you are just nothing if not a Canadian … anyway they [the lassies] are immune to the skirl of the bagpipes as yet’.62

By the start of May, British morale was described as ‘very high’. ‘At its highest’, the censors noted, ‘it is expressed by real fighting men keen to get at the enemy. At its lowest by those who long for the end, and yet are ready to face the inevitable fight to achieve that end.’ Throughout the mail there was again, however, ‘a growing sense of tension’, indicating, according to the censors, that the men had reached a ‘peak of emotional readiness for action’. A corporal in the Royal Army Supply Corps wrote, ‘I’m sure the lads won’t stop at anything, they are like alarm clocks, wound up ready for the off. It’s telling on our nerves, but what must it be like for jerry.’ The prevalent attitude among troops, and most noticeably among NCOs, was a desire to get the whole thing over with so, as a sergeant in 9th Royal Tank Regiment put it, ‘we can settle down to a little life’. The main worry, according to the censors, was that the high state of morale was ‘often verging on over optimism’.63

Canadian mail told a similar story. An ‘undercurrent of tension’ was ‘discernible in the letters’ and ‘a strong feeling of nostalgia … the desire to be able to return to Canada and to resume the business of living’ was ‘very marked’. Nevertheless, the mail indicated that the troops were in ‘mental and physical readiness for action’. Confidence in equipment and training and in victory was ‘evident’, and there were ‘many indications of a fine esprit de corps’. Morale, it was confidently stated, was ‘high’, although the censors noted frankly, ‘there are no heroics’.64

By the end of May, as the invasion creeped ever closer, the strain of what must have seemed the interminable wait was beginning to take its toll on the men. British morale was still described overall as ‘very high’, but the censors reported that ‘the mail is subdued in tone, and there are no highlights … The expression “browned off” is freely used throughout the whole mail and is inseparable from the desire for the long awaited Second Front to open, to get into the fight, to get home again and back to “civvy street”.’ ‘To sum up’, the censors concluded, ‘this is the mail of a civilian army with absolute faith in the rightness of its cause [the necessity to defeat Germany], with no love of soldiering, but with a grim determination to see this thing through and the sooner the better’.65

In the days running up to D-Day at the start of June, the slightly subdued character of the British troops’ mail continued, and, according to the censorship summaries, morale dropped somewhat.66 The men did not enjoy being cooped up in camps and ‘a minority showed strong resentment’, especially when these camps were near large towns.67 The censors pointed to ‘frequent abuses’ of twenty-four-hour leave privileges during this period; but it was not clear whether overstaying was ‘deliberate or due to transport difficulties’.68 There was clearly a strong feeling among some of the units that had fought in North Africa and the Mediterranean that they ‘should not be asked’ to take part in the invasion. Absence without leave was particularly prevalent in these formations, notably in 50th Northumbrian Division stationed in the New Forest, with, according to one source, ‘well over 1,000’ cases and ‘considerable unrest’ reported more generally.69 Some men in the division used ‘blast grenades and Bangalore torpedoes to blow holes in the fences and liberate themselves’. Soldiers of 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, who had fought at El Alamein and who would serve with 11th Armoured Division in Normandy, were ‘virtually mutinous’, according to one officer, inscribing ‘No Second Front’ on the walls of their barracks at Aldershot.70 It was ‘clear’, therefore, in the words of the censorship summaries, ‘that a postponement of the operation might have had serious repercussions’.71 Eisenhower’s decision to launch the invasion on 6 June, in spite of the inclement weather and obvious risks, must be understood in this light.

As final preparations were made for D-Day, then, there were a number of issues that were acting negatively on the morale of British troops. In contrast, the morale of the Canadian troops rose noticeably in the same period. Reaction to the eventual Canadian successes in Italy ‘had an inspiring effect’,72 with the censors reporting that ‘fighting spirit’ was ‘outstanding’ and morale ‘very high’. The men were ‘supremely confident’ and ‘regimental pride and fine esprit de corps is evident’. The clear message from the mail was that ‘we are ready … this is it’.73 The Canadian troops seemed much more positively disposed towards their Commonwealth brethren than their British counterparts. They had clearly enjoyed their time in England. The censors noted that ‘the Canadian appreciation of English qualities is often embarrassing’. A captain at HQ 21st Army Group wrote, ‘there may be better fighters in the world than [the] English, but not many; and there are no braver fighters. No braver people. And despite the venomous implications of the British caste system there are no more democratic people in the world’. A private in the Canadian Signals wrote that ‘we have come to look on this place as our home’, while a signalman in 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade remarked, ‘I like England quite a lot, unlike the States or Canada everybody isn’t always in a rush to make money.’ ‘Many things have been said of the conservativeness of English people’, wrote a private in the 18th Canadian Field Ambulance, ‘but take it from me, there is nothing more genuine than the hospitality of England’s working class.’74

Developments on the Canadian home front only served to reinforce this air of positivity. There was ‘widespread praise for the speed of delivery of inward mail from Canada’; this had a ‘marked effect on the happiness of the Troops’. The censors pointed to ‘enthusiastic references to the 6th Victory Loan’. These war bonds were remarkably popular; the Army deferred a portion of the men’s pay each month and many thought it good sense to buy a bond to gain a higher interest rate on their savings.75 As D-Day approached, Canadian mail was almost exuberant. The 3rd Canadian Division as a whole, according to the divisional psychiatrist, was in fine shape. ‘The general morale throughout the division is excellent. The troops are relaxed and in the highest spirits. Some of the officers and practically all of other ranks feel that our troops will go twenty-five miles in one day, that they have the firepower, the naval support and air superiority. There seems to be no talk of hazard.’76

Notwithstanding the domestic issues undermining British morale in the long waiting period before the invasion, by the morning of D-Day, 6 June, it appeared that all the troops, British and Canadian, were in ‘fine fettle!’77 The Canadian censors noted that their troops ‘feel that their hour is about to come. They are ready, fighting fit, tough, well trained, confident t[roo]ps, proud and … longing to show their mettle. They say that this is the moment they have lived for, trained for, left their homes for’.78 ‘First impressions’, according to British censorship reports from Normandy, were that morale was ‘excellent, particularly in the case of 6 Airborne Division’.79

The Assault

High levels of motivation and commitment were to prove essential in the hours that lay ahead. Waiting for the troops in the general area of north-west France ranged some sixty German divisions (including ten panzer divisions), deployed in thirteen corps and in four armies, First, Seventh, Fifteenth and Fifth Panzer (Panzer Group West). Those formations that would fight in Normandy came under Field-Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Army Group B, which was in turn under the overall supervision of Field-Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the C-in-C West.80

These forces ranged themselves behind the formidable defences of the Atlantic Wall. After the Dieppe raid in 1942, the German High Command had ordered the building of a set of fortifications intended to make an attack from the air, sea or land ‘hopeless’.81 The main strength of the Atlantic Wall, which was supposed to stretch from Norway to the Spanish frontier, concentrated for obvious reasons between Dunkirk and the Somme estuary.82 Those defences that were complete in Normandy, ranged from small concrete shelters to elaborate fortified gun positions. Most of these ‘were built around a gun casement protected from air or naval assault by six feet of concrete on the seaward side and four feet on the roof’. These positions typically also included pillboxes and concrete pits, known as ‘Tobruks’, housing machine guns and mortar positions. The large concrete bunkers, in addition to underground installations, offered protection against bombardment. No continuous secondary line of defence existed behind the coastal strip; but, reserve companies and field and anti-tank artillery were placed inland. These units were intended to provide some depth to the defences and contain a breakthrough until help arrived in the form of mobile reserves.83

Since the spring of 1942, 716th Infantry Division with two Ost, or East, battalions of captured Russians and Poles, had been responsible for defending the area which was now marked for the Allied assault. In March 1944, 352nd Division, a ‘first-class mobile infantry’ outfit, arrived to strengthen the defences, assuming control of the western part of the Calvados coast. These forces were further supplemented by the arrival of 21st Panzer Division around Caen in May.84 By 6 June, the German Army in Normandy had more formations than the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had originally believed safely manageable by the D-Day forces.85

In order to overcome this challenge, the Western Allies had forty divisions at their disposal, twenty-three of which were in Bradley’s 12th US Army Group and seventeen (thirteen British, three Canadian and one Polish) in Montgomery’s 21st Army Group.86 This amounted to only two-thirds of the German divisions in theatre, but German divisions, much as was the case in Italy, were not equivalent in manpower or firepower to Allied ones; a German panzer division, for example, had about 160 tanks as compared to about 240 in an American or British Armoured Division, while a German division of any kind had about 50 field or medium guns, against about 90 in an Allied division. The 21st Army Group also had eight independent armoured or tank brigades, six brigades of heavy, medium and field artillery and six engineer groups. Overall, the Allies had a superiority of about 3:1 in tanks, of about 3:2 in medium and field artillery, and a rough equivalence in infantry battalions. In the air and at sea they enjoyed an overwhelming superiority.87

In spite of these advantages, the force-to-force ratios on land clearly left Montgomery vulnerable if the Germans could concentrate their forces in the area of the bridgehead quicker than his own.88 The Allies had to gain operational surprise to ensure that the landing force came up against as few German formations as possible and buy time to allow the build-up of troops before the full weight of the Wehrmacht could be thrown against the bridgehead. To this end, a complex and multidimensional deception plan, Operation ‘Bodyguard’, was put in place to mislead the Germans as to the place and timing of the attack.89 It was hoped that the Germans would be induced to deploy their troops as far away from Normandy as possible.

As part of this overall plan, Operation ‘Fortitude South’ was conceived to pin down German defenders in the Pas de Calais for as long as possible after the invasion. To achieve this goal, the German High Command had to be convinced that there were forces available for two attacks. One would be a diversion on the shores of Normandy and a second would be a real invasion across the Channel at the shortest point. Every effort was made to draw attention to the south-east coast of England, the obvious launching point for an attack on the German defences at the Pas de Calais. Dummy wireless traffic, troop concentrations, landing craft, vehicle parks, guns, tanks and field kitchens were set up. Men drove army trucks back and forth to leave visible tyre tracks. A dummy oil storage complex near Dover was even inspected by King George VI and Montgomery. Fighter patrols flew over tent cities in order to maintain the charade. General Patton was put in charge of the fictitious First United States Army Group (FUSAG), as the Germans fully expected the Allies ‘most talented’ general to command the invasion. Spies and double agents disseminated information supporting the fiction that FUSAG would launch the main invasion at the Pas de Calais.90

The Germans never spotted the massed FUSAG tent cities in southern England, as few German aircraft managed to penetrate Fighter Command’s defences, but, by mid-1944, there was every indication that the double agents had convinced the Germans that Normandy was a diversion. This growing sense within the German High Command that the invasion would be launched at the Pas de Calais was reinforced by their misinterpretation of the intent of the massive aerial offensive launched by the Allied Air Forces to isolate Normandy from the rest of France and prevent German reinforcements reaching the front after the invasion (‘The Transportation Plan’). The Germans believed that these co-ordinated aerial attacks were designed to prevent reinforcements from Normandy reaching the Pas de Calais, and not the other way around. The attacks were so successful that, by D-Day, no routes across the River Seine north of Paris remained open and only three road bridges across the river were functional between Paris and the sea.91 Normandy, to all intents and purposes, had been cut off from the rest of the Continent.

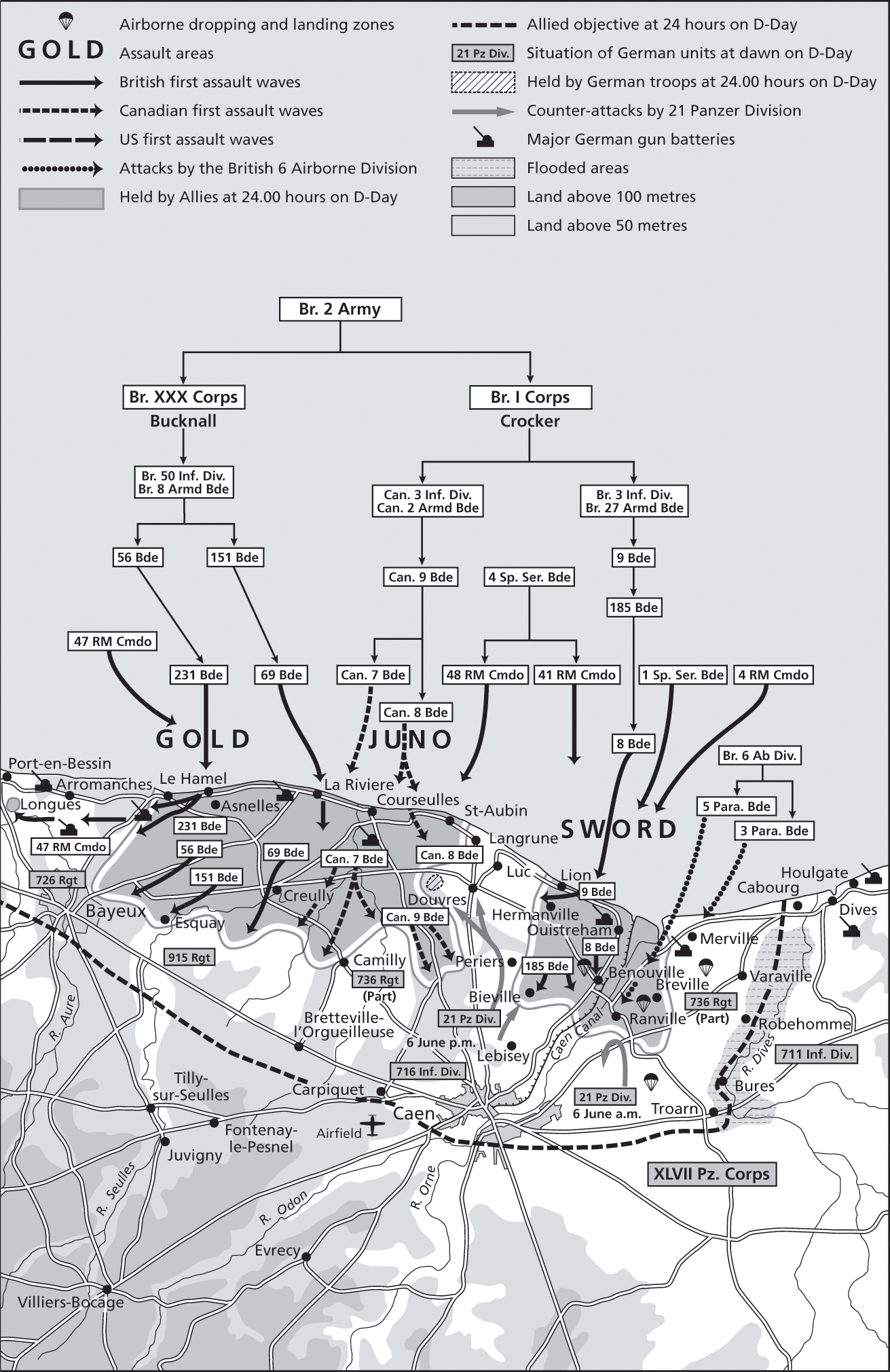

Even with these key enablers in place, the scale of the challenge for those assaulting the beaches was immense. The plan of attack was to land on a 50-mile front along the Normandy coastline (see Map 13.1), incorporating two sectors. The Americans in the west were tasked with taking Utah and Omaha beaches and the Anglo-Canadian Second Army in the east were assigned to the taking of Gold, Juno and Sword beaches. Montgomery’s operational plan for Normandy called for Second Army, on taking the beaches, to push inland and capture the high ground to the south-east between the city of Caen, about 10 miles inland, and the town of Falaise, 20 miles further to the south. It was hoped that the Anglo-Canadian force would thus threaten the road to Paris, forcing the Germans to commit in the eastern sector. This would facilitate First US Army’s drive to capture Cherbourg and the Brittany ports to the west and north of the initial beachhead, a key requirement for the logistical sustenance of the invasion; then the US forces could turn east towards Paris. Second Army’s push south would also involve the capture of valuable territory to the west of Caen, near Carpiquet, land suitable for airfields. Caen, it was planned, should be taken on the first day, before the Germans had the chance to react and reinforce the area. Should the Anglo-Canadian forces fail to take the city, there was a real danger that the invasion would bog down in intense and costly fighting. Should the ‘eastern wall’ fail, the whole bridgehead, according to Dempsey, the commander of Second Army, ‘could be rolled up’ from the flank.92

Map 13.1 D-Day, 6 June 1944

To prevent this from happening, three airborne divisions were used to protect the eastern and western extremities of the bridgehead. The 82nd and 101st US Airborne Divisions were employed in the west while 6th British Airborne Division was tasked with protecting the eastern flank by taking and holding the Breville Ridge. ‘This imposing long wooded ridge was the key to the whole position East of the Orne’ as it overlooked the ‘greater part’ of the British I Corps front around Caen. The 6th Airborne, therefore, had first to capture the crossings over the River Orne and the Caen Canal, between Caen and Ouistreham, to ensure that forces on the ridge maintained contact with the main invasion force. It then had to take Merville battery (a key position which could fire onto Sword beach and the sea approaches) and destroy four bridges over the River Dives to the east of the ridge, in order to delay any German reinforcements or counter attacks. Finally, the seaside towns of Salanelles and Franceville Plage were to be seized and as much of the coastal strip between these places and Cabourg on the mouth of the River Dives cleared of the enemy. For this, 6th Airborne had Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Commando Brigade under command.93

In the early hours of 6 June, the bridges over the River Orne and Caen Canal were captured intact in daring and well-prepared glider-borne raids. Elsewhere, parachute drops created havoc and confusion behind German lines, in spite of the fact that many units became dispersed and disorientated (in most cases achieving only 40 per cent of their intended drop strength). Brigadier Hill, of 3rd Parachute Brigade, had warned his men not to be ‘daunted if chaos reigns’.94 Chaos did reign; the aerial bombardment intended to soften up Merville battery (one of his brigade’s objectives), missed its target; only 150 out of the 600 men of 9th Parachute Battalion intended for the assault scheduled at 0430hrs could be found and brought together in time for the attack. In spite of these difficulties, the objective was eventually taken.95 The 6th Airborne Division, in a remarkable achievement, attained all of its main objectives on D-Day, setting the conditions for the seaborne invasion that was massing in the English Channel.96

By the early hours of 6 June, the vast Allied armada, made up of around 130,000 troops, 12,000 aircraft, 1,200 fighting ships and 5,500 landing and naval craft, was sitting off the five assault beaches along the Normandy coast.97 The attack opened at 0300hrs with over 1,000 British bombers dropping around 5,000 tons of bombs on and around German positions.98 In spite of the incredible weight of firepower unleashed, the bombardment proved largely ineffective. The poor weather, which had allowed the unseen crossing of the Allied invasion fleet and the achievement of operational surprise, limited the impact of the bombing programme. Few enemy positions were hit. Typhoon squadrons assigned to attack beach targets found the winds and overcast skies a serious challenge.99 The bombardment from the sea was only marginally more effective. Major John Fairlie, a Canadian artillery officer, who conducted an exhaustive investigation of Juno beach after the battle, concluded later that naval fire had done ‘no serious damage to the defences’.100

It was in this context that the assault troops were to land; and, as Terry Copp has put it, ‘no one who examines the events of the first hours of D-Day can fail to be impressed by the accomplishments’ of these men (see Illustration 13.1).101 The 3rd Division, of I Corps, landed on Sword beach, the furthest east of the five Allied landings; its objective was to seize Caen and, along with 6th Airborne Division, to hold the left-hand flank of Second Army. 3rd Canadian Division, also of I Corps, assaulted Juno beach, in the centre of the Anglo-Canadian sector; it was tasked with capturing the area around Carpiquet, a roughly similar distance inland. The 50th Northumbrian Division, of XXX Corps, landed on the right-hand flank (to the west) on Gold beach; it was tasked with pressing inland towards Bayeux, somewhat closer to the coast than the other two objectives, and to link up with the Americans advancing from Omaha beach to the west (on their right flank).

Illustration 13.1 Troops of 3rd Canadian Division disembark from a landing craft onto Nan Red beach, Juno area, near St Aubin-sur-Mer, at about 0800hrs, 6 June 1944, while under fire from German troops in the houses facing them.

What the men experienced was, by any standard, an ordeal. The landing craft of 50th Northumbrian Division, with the assault brigades on board, were lowered into the water at 0415hrs. There they spent the next three hours rising and falling with the waves as they awaited touch down at H Hour +5 (H+5), namely five minutes after the landings in this sector were due to begin. At about 0600hrs the five cruisers and nine destroyers assigned to provide fire support opened up with over 100 guns. This was accompanied from H-60 by the guns on the landing ship tanks (LSTs) and by the landing crafts’ own weapons. At H-12 and H-7 the four rocket ships supporting the assault discharged their fire. The roar, by all accounts, was terrifying.102

Though supported by the firepower of the massive Allied armada, it was perfectly clear to the individuals in the landing craft that they alone carried the terrible responsibility of assaulting the beaches. As the Queen’s Own Rifles, 3rd Canadian Division, approached Juno beach, one man recalled:

As we moved further from the mother ship and closer to the shore, it came as a shock to realise that the assault fleet just behind us had disappeared from view. Suddenly there was just us and an awful lot of ocean … Ten boats stretched out over fifteen hundred yards is not really a whole lot of assault force. The boats began to look even tinier as the gaps widened, with more than the length of a football field between each.103

When the order ‘down ramp’ came, there was nothing for the men to do but race for the sea wall and endure the heavy machine-gun and mortar fire unleashed by the German defenders. Many of the Duplex Drive (DD) amphibious tanks, which were to plunge ashore and arrive ahead of the first wave, were not launched or became stalled in the heavy seas. Some units suffered heavily, with their platoons losing up to two-thirds of their men.104 In the ‘Queen White’ and ‘Queen Red’ sectors of Sword beach, the first wave suffered 30 and 45 per cent casualties respectively. For the first two waves, overall the figures for ‘Queen White’ and ‘Queen Red’ were 22.5 and 28 per cent, ‘the highest of any of the Anglo-Canadian beaches’. Close to 15 per cent of all armoured vehicles landed at Sword were knocked out by enemy gunfire.105

Overall, casualties in the assault divisions were lighter than expected. At Sword, it was thought that casualties would amount to as high as 72 per cent in the first wave.106 Major W. N. Lees, an Australian officer attached to the British Army in North-West Europe, who compiled a detailed 360-page report on the campaign, noted that the British and Canadians had anticipated 7,750 casualties on D-Day, approximately 3.1 times the actual casualties suffered (around 2,515). The Historical Section at the Cabinet Office estimated that 6th Airborne Division suffered 1,022 casualties up to 0600hrs on 7 June 1944, 20 per cent of its landing force on D-Day. The 3rd Division suffered 957 casualties, 9 per cent of its landing force and 3rd Canadian Division suffered 1,063 casualties, 7 per cent of its landing force. The Historical Section did not provide figures for the first day for 50th Northumbrian Division, but the casualty returns for 9 June estimated it had suffered 801 casualties by this date.107 The invasion had by no means been a walk over.

Nevertheless, it was clear that the carefully prepared plan for the assault had to all intents and purposes worked. The Germans had been taken completely by surprise. It is apparent from German reports that they had anticipated a large-scale operation only where the point of landing was in the neighbourhood of at least one good harbour.108 They did not expect an invasion near cliffs, unless they had a wide foreshore, or where there were strong currents, surf, reefs or shallows. The invasion was expected in fair, calm weather, with a rising tide and at a new moon. As it turned out, the Allies commenced the landing at full moon, away from large harbours, in a strong wind with low cloud ceiling and a rough sea; they landed at some points at sheer cliffs, and in water stated by German naval experts to be impassable by reason of underwater reefs and strong currents; the first wave went ashore at lowest ebb. Thus, it was possible to pass the foreshore obstacles almost without casualties, while bright moonlight had facilitated the dropping of parachutists and airborne troops on terrain that had been considered unsuitable for air landings and had not therefore been blocked or defended sufficiently.109

The Second Army Intelligence Summary for the end of D-Day was damning in its criticism of the German defence. The opposition had been ‘less than anticipated’. It was evident that ‘the place of the … invasion [had] remained a secret’ and that ‘a considerable measure of surprise’ had been achieved. The German defence of Normandy had clearly ‘failed’; ‘no other conclusion’ was ‘possible when it is realised that within an hour of H hour the landing troops were passing through the beaches’.110 Many of the assaulting British and Canadian troops agreed with this appraisal and were decidedly unimpressed by what they met on the beaches. Major J. N. Gordon of the Queen’s Own Rifles recalled that the Germans encountered by his company were ‘mere boys’ and ‘very frightened’ and ‘ran away’.111 The British censors noted that ‘comments by Air and Seaborne formations on enemy troops showed one marked difference. Airborne troops referred to the enemy with respect, whereas Seaborne troops emphasised the poor quality of the Static German Beach formations encountered during the early stages of the operation’.112 One observer noted that in some strongly fortified positions ‘the enemy fought well only submitting when he was overwhelmed by fire and assaulted with the bayonet’.113 In others, German resistance was less determined and ‘prisoners were many’.114 The Canadian censors noted that the troops had ‘a poor impression’ of the POWs they had seen. A private in the Highland Light Infantry of Canada wrote that ‘we have taken quite a few prisoners and they aren’t the ferocious people they are described as. All of them pretty young and most of them mighty scared.’115

Much credit must go to the preliminary bombardment, in spite of its inaccuracy. While the material effects had been underwhelming, British, American and German reports all emphasised the extent to which it had demoralised defensive units on the beaches and the reserves further back.116 An Allied report on ‘German Views on the Normandy Landing’ produced in November 1944 and based on twenty-three captured documents, emphasised that although minefields laid near the coast had been ‘blown up, and proved useless’ and barbed wire entanglements had been ‘broken down’, concrete emplacements and slit trenches, especially when covered with strong wooden lids, had allowed troops to survive the inferno. By comparison, ‘the moral effect’ had been immense:

Even where it was not reinforced by simultaneous air bombing, the drum fire [naval bombardment] inspired in the defenders a feeling of utter helplessness, which in the case of inexperienced recruits caused fainting or indeed complete paralysis. The instinct of self preservation drove their duty as soldiers, to fight and destroy the enemy, completely out of their minds.117

The sheer scale of Allied mastery of the air undoubtedly contributed to German soldiers’ feelings of helplessness. In February 1944, Allied planners had expected to face 1,650 first-line German aircraft on D+1, perhaps joined by 950 more. While the Luftwaffe did throw most of its fighters into the fray during ‘Overlord’, they numbered only 1,300. On D-Day itself, the Luftwaffe flew only 319 sorties, while the Allies flew 12,015 (a ratio of 1:38).

Moreover, many of the troops, according to captured German documents, ‘were suffering from overstrain as a result of incessant labouring on field works, as they were ordered to do from the first light to dusk for weeks before the invasion’. In many front-line units, a high percentage of men were convalescent personnel, ‘fit for labour service only’ or ‘conditionally fit’, or were recruits with only four weeks training. The NCOs were mainly specialists without infantry training, for example tank repairers, German Air Force ground staff etc.118 Poles and Alsatians, pressed into service in the army, proved particularly vulnerable and ‘wholesale desertions’ were reported.119 It would appear, then, that particularly on D-Day, the performance of German troops opposing the Anglo-Canadian landings had been significantly inhibited by the psychological effects of Allied firepower and the quality of their training.

Nevertheless, in spite of the problems facing the German defenders on 6 June, by midnight, the three British and Canadian assault divisions had failed to take their D-Day objectives. In the morning, 3rd Division had cleared the beach defences. But, by the afternoon, as it pushed inland, its advance began to slow as it encountered stiffer opposition. By the end of the day, it had secured the line along the River Orne to the east, making contact with 6th Airborne Division, and a bridgehead had been established. But the furthest penetration inland had only got as far as Lebisey Wood, just to the north of Caen.120 The assault battalions of 50th Northumbrian Division completed the first phase of the attack not long after the prescribed time; apart from 1st Hampshires, 231st Brigade, who encountered bitter fighting in Le Hamel, little trouble was experienced.121 By the end of the day, it had linked up with the Canadians advancing inland from Juno beach but it had not connected with the Americans near Omaha. The follow-up troops of the reserve brigades, 8th Armoured, 56th and 151st Infantry, had only reached their assembly areas; this was in spite of the fact that the enemy had failed to launch a determined counter-attack. Most importantly, just like 3rd Division, it had not taken its D-Day objective, the town of Bayeux.122 The 3rd Canadian Division, by comparison, fared better;123 beach clearance had ‘proceeded rapidly’124 and ‘with several hours of daylight left … there was little doubt that the 9th [Canadian] Brigade could reach Carpiquet’. But with matters unfolding less well in the British sectors, and with 3rd British Division being counter-attacked by 21st Panzer Division, Dempsey ‘ordered all three assault divisions to dig in at their intermediate objectives. This decision was relayed to subordinate commanders sometime after 1900’ on D-Day.125

Controversy

At first glance, it is hard to reconcile the failure of the assault divisions to take their objectives with the reportedly excellent morale of the British and Canadian soldiers and the poor performance of the German defenders on D-Day. As Lees put it, ‘opposition on the British beaches was less than anticipated, and at the same time, the rate of advance inland was, in many cases, slower than planned’.126 According to the Canadian Official History, the Anglo-Canadian forces had missed the opportunity to seize Caen and the original D-Day objectives because they had not followed up the initial assault with sufficient aggression.127 German reports indicated that ‘after the first infiltration in the coastal defence zone’ the Allies advanced ‘only hesitantly’,128 a perspective shared by Chester Wilmot, the Australian war correspondent, who thought that 3rd Division had noticeably ‘dropped the momentum of the attack’ as the day wore on.129

Montgomery had warned precisely against such behaviour. On 14 April 1944, he instructed Dempsey to advance armoured brigade groups inland from the beaches as soon as possible to secure crucial objectives, most obviously Caen:

Armoured units and [brigades] must be concentrated quickly as soon as ever the situation allows after the initial landing on D-day; this may not be too easy, but plans to effect such concentrations must be made and every effort made to carry them out; speed and boldness are then required, and the armoured thrusts must force their way inland.

I am prepared to accept almost any risk in order to carry out these tactics. I would risk even the total loss of the armoured brigade groups.130

He stressed the point again in an address to senior commanders on 21 May:

Every officer and man must have only one idea and that is to peg out claims inland and to penetrate quickly and deeply into enemy territory. To relax once ashore would be fatal … senior officers must prevent it at all costs on D-Day and on the following days. Great energy and drive will be required.131

The D-Day plan clearly called for both ‘boldness and dash’. Dempsey argued after the war that it had been imperative to grab as much as possible in the confusion generated by the landings.132 As one man from the Norfolks later wrote, ‘you can do with a platoon on “D” Day, what you cannot do with a battalion on “D”+1 or a division on “D”+3’.133 But, that same confusion, accompanied by friction and chance, was also the undoing of Second Army’s ambitions. As events did not play out exactly as expected, platoon, company, battalion and brigade commanders all had to adapt in contact with the enemy.

This required excellent morale, but in spite of the positive appraisal offered by the censorship summaries, it is difficult to ignore the criticisms of Wilmot and others. It is not possible to assemble definitive evidence on the state of morale on 6 June; sickness, battle exhaustion and desertion/AWOL rates are not available in the archives for the first five days of the Normandy campaign; the first figures available are for the week ending 17 June. Moreover, the censorship summary for British troops, 1 to 14 June 1944, was based on 145,000 letters written before D-Day and only 8,000 written following the landings. It can be confidently concluded then that morale was ‘high’ before the assault, but it is less certain that it was ‘excellent’ both during and after D-Day. The compilers of the summary acknowledged that ‘the special conditions prevailing’ made it ‘possible to report only on the broadest features reflected in the mail. The comparatively small proportion of overseas mail examined can only carry a first impression of the operational conditions.’ The British censors picked out 6th Airborne Division for special mention, and it is notable that Richard Gale, its commander, also highlighted its high morale and the lack of military crime in the division before D-Day. ‘All seemed to be imbued with the seriousness of the task in hand; all had a real and deep sense of their responsibilities; and all seemed impressed with the sacredness and justice of the cause for which they were trained and eventually going to fight.’ ‘Several times’, according to Gale, ‘the situation appeared serious [during the first day of fighting], but always it was restored by the fine leadership of the junior commanders and the determination and initiative of the troops.’134 The 6th Airborne was the only division to secure its D-Day objectives. Similarly, Canadian morale, according to the censors, appeared to be exuberant, and, perhaps, in this context, it is not surprising that they would likely have reached their objectives had they not been halted by Dempsey on the evening of 6 June.135

Elsewhere, behaviour was more consistent with ‘high’ rather than ‘excellent’ morale. On Sword beach, stiff resistance at some strong points and casualties among key personnel delayed clearance of the beach. The assault engineers cleared none of the planned eight exit lanes in the first 30 minutes; it was 50 minutes before the first lane was open, with a total of seven available after 150 minutes. One strong point, ‘Cod’, took over three hours to clear. These delays had a ‘cascading effect’ as D-Day progressed;136 combined with an ‘unexpectedly high tide’, they led to a great deal of congestion on the shore. This, in turn, ‘delayed the start of the advance inland’ (see Illustration 13.2).137

Illustration 13.2 British Commandos advance towards Ouistreham, Sword area, 6 June 1944. In spite of the notable feat of arms of D-Day, controversy still rages over whether British and Canadian forces should have pushed more aggressively inland to take their D-Day objectives.

In the confusion that ensued, the infantry, under strict instructions to push ahead, got separated from its supporting arms. The poor weather made matters worse by inhibiting the use of close air support.138 Tactical intelligence was poor, the price of strategic security; reconnaissance flights had been launched at a ratio of two in the Pas de Calais area to one in Normandy in an attempt to mislead the Germans regarding Allied intentions. The British, therefore, did not know that 352nd Infantry Division had raised its strength by 150 per cent on Gold beach, nor did they know that 21st Panzer Division had placed its anti-tank units and half its infantry between the River Orne and Caen, right in the path of 3rd Division’s line of advance.139

In the context of 21st Army Group’s training, the manner in which events unfolded proved problematic for the rapid advance envisaged by Montgomery. Formations had been taught primarily to move forward to designated objectives in controlled bounds and dig in at the first sign of an enemy counter-attack. On calling in artillery support, Anglo-Canadian units, even those as small as ten-man sections or thirty-man platoons, were instructed to advance to the next objective behind a curtain of bullets and high-explosive artillery shells.140 Crerar, especially, could not have been more explicit on this matter prior to the invasion, and, indeed, it was a message continuously reiterated by commanders in Normandy.141 A more dynamic approach once the beaches had been taken would have required Second Army to utilise its battle drills in preference to firepower-heavy tactics.142 In the complex, fearful environment of D-Day, this was an unrealistic expectation.143

Particularly in the case of the two largely inexperienced divisions, 3rd British and 3rd Canadian, a mechanised firepower-heavy approach had been prioritised in training. Additionally, the veterans of 50th Northumbrian Division had fought under Montgomery in North Africa and Sicily and were inclined, according to some reports, to assume that they had cracked the tactical challenges of modern warfare and did not require alternative training in preparation for Normandy.144 Thus, all three divisions, under extreme stress, relied on the practices with which they were familiar. By comparison, 6th Airborne Division was trained, according to its commander, to exercise individual initiative in battle and embrace the challenges and opportunities of mobile warfare.145

The hybrid doctrinal formula that had evolved in the British and Canadian Armies had conditionally embraced battle drill but clearly subordinated it to mechanised firepower. In the light of the extremely ambitious objectives set for D-Day, this conceptual balance and understanding appears to have been inappropriate, much, indeed, as it had been in Sicily and Italy. Montgomery, who wished for Second Army to fight a mobile and aggressive battle on landing in Normandy, had only himself to blame. He had stressed in his seminal ‘Brief Notes for Senior Officers on the Conduct of Battle’, of December 1942, that ‘all commanders’ had to ‘understand clearly the requirements of battle; then, and only then, will they be in a position to organise the proper training of their formations and units’. ‘In fact’, he said, ‘the approach to training is via the battle.’146 Such an understanding, as encapsulated in the ‘Jungle Soldier’s Handbook’ and the ‘Jungle Book’, had underpinned the training revolution that had taken place in the Far East. If soldiers were to truly use their initiative in combat, a key requirement for success in modern warfare, they had to be trained consistently to do so. ‘The Instructor’s Handbook’, in the eyes of too many commanders, did not provide the solution to the tactical problems they expected to face in Normandy. Moreover, Montgomery, in spite of his increasing understanding of the limits of the ‘Colossal Cracks’ approach, left training to his subordinates, who were still overwhelmingly affected by the experiences of the first years of the war. In this respect, it is apparent that although Montgomery and the War Office adequately prepared their men for another ‘break-in’ battle (the beach assault), they did not, in light of the inevitable frictions inherent in a complex multinational and tri-service amphibious operation, prepare the men fully for the ‘breakout’, the exploitation phase of D-Day.

Such an observation does not take away from what the official historian described as the ‘notable feat of arms’ of D-Day.147 The achievement of putting ashore 75,215 men and landing another 7,900 from the air on the first day of the invasion of North-West Europe ranks with any in the history of warfare.148 But, the factors that prevented Anglo-Canadian units from reaching their D-Day objectives did point to problems that would affect 21st Army Group recurrently over the course of the campaign. The British and Commonwealth Armies in the West were still searching for a way not only to wear down the Wehrmacht in battle, but to annihilate it in great clashes of fire and manoeuvre.