2 - A Tale of Venetian Skin: The Flaying of Marcantonio Bragadin

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

ON 24 November 1961, with very little fanfare and almost no audience – only far-removed descendants and a few scientists – a niche tomb in the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo was opened. It was not entirely known what would be found. For many years, locals suspected that there would be nothing, that the legends were false. The tomb, marked on its outside by an urn, a bust and an identifying inscription, was that of Marcantonio Bragadin, the heroic Venetian defender of Famagusta during the attack of the Ottoman Turks in 1570–1.

Inside the tomb was a leaden casket, too short to carry a body. But, then again, it was not a body that had been interred. When opened, several pieces of skin were revealed – the skin of one who had been flayed alive. Beyond the presence of skin, however, accounts from 1961 report little else. For this, one must go to a description from the 1596 transmission of Bragadin's skin from the Venetian church where it first rested, San Gregorio, to the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paulo:

Esa era piegata in ampiezza d’un foglio di carta, salda e palpabile come fosse un pannolino; vi si vedevano i peli del petto ancora attaccati, et alla mano destra, che era scorticata, la dita non compiute di scorticare con l’unghie che sembravano ancora vive.

[[The skin] was folded to a size of a sheet of paper, solid and palpable as a napkin; they could see his chest hair still attached, and on the right hand, which was flayed, was a nail that still seemed alive].

Between 1571 and 1596 the flayed skin had already travelled widely and, at a time when the Venetian governmental leadership was touting victory at Lepanto as a sign of future success, Bragadin's skin reminded the citizens of Venice of their defeat at Cyprus and what the past had already brought. Bragadin's skin was a testament to his people that flaying was one vicious, inhumane effect of fighting a vicious, inhumane enemy; the maintenance of this legendary artefact was a powerful reminder to Venetians of their constant foe, the Ottoman Turks.

- Type

- Chapter

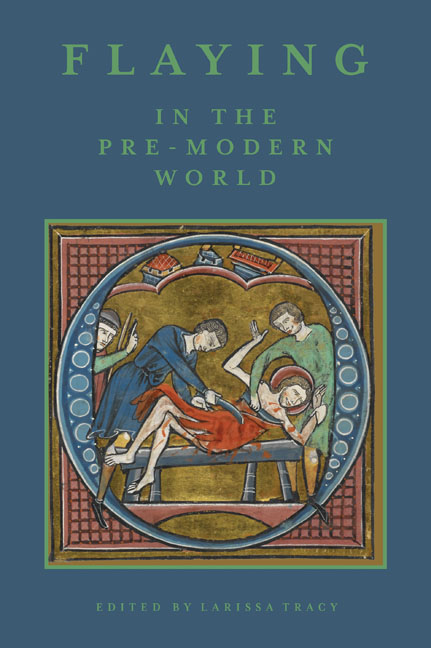

- Information

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 51 - 70Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017