Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The human face

- 2 The history of facial reconstruction

- 3 The skull

- 4 The relationship between hard and soft tissues of the face

- 5 Facial tissue depth measurement

- 6 The Manchester method of facial reconstruction

- 7 The accuracy of facial reconstruction

- 8 Juvenile facial reconstruction

- References

- Select bibliography

- Index

2 - The history of facial reconstruction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The human face

- 2 The history of facial reconstruction

- 3 The skull

- 4 The relationship between hard and soft tissues of the face

- 5 Facial tissue depth measurement

- 6 The Manchester method of facial reconstruction

- 7 The accuracy of facial reconstruction

- 8 Juvenile facial reconstruction

- References

- Select bibliography

- Index

Summary

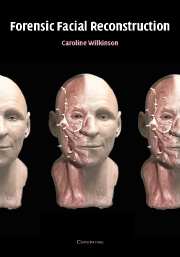

Facial reconstruction is the scientific art of building the face onto the skull for the purposes of individual identification. Scientific art is the application of artistic skills whilst following scientific rules. This procedure has been exercised for over a century and there exist three main techniques:

(1) The two-dimensional 2-D artistic representation of the face, usually drawn over a photograph of the skull.

(2) Three-dimensional 3-D facial reconstruction using a sculptural technique.

(3) Three-dimensional facial reconstruction using computer-generated images.

These techniques share the common principle of relating the skeletal structure to the overlying soft tissue. The technique of superimposition, which has a long history in the forensic arena, is not considered here since it requires photographic evidence of a suspect in order to connect an individual with the unidentified skull (see Iscan & Helmer, 1993; Knight & Whittaker, 1997; Whittaker et al., 1998). The artistic and sculptural reconstruction techniques have been used for recognition in forensic identification investigations worldwide, and these procedures are usually employed when the police do not have a suspect for identification.

Background

The fact that the facial reconstruction procedure exists at all is a reflection of our unlimited fascination with human faces, and this preoccupation has led to a more specific interest in the faces of people from the past. The remains of people are constantly excavated and the desire to discover how those people may have appeared has been seemingly limitless. The history of modelling a face onto a skull is extensive and there are numerous early symbolic examples (see Figs.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Forensic Facial Reconstruction , pp. 39 - 68Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2004

- 2

- Cited by