1 Introduction

Under European Union (EU) law, geographical indications (GIs) are protected under three guises: the protected GIs (PGI), the protected designations of origin (PDOs), and the traditional specialities guaranteed (TSGs). For the EU, the protection of its GIs in and outside of Europe is a very relevant economic issue, as the value of GI products in 2010 was estimated at €54.3 billion, of which the sale of wines accounts for more than half.Footnote 1 It is no surprise that the EU is vigorously trying to obtain protection for its GIs in major trade partner nations. However, in the context of the World Trade Organization (WTO), New World nations, most notably the North Americas, Australia and New Zealand, have consistently rejected the notion of a multilateral register for GIs that is dominated by European claims. Thus, it comes as no surprise then that in the context of the WTO negotiation mandate contained in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)Footnote 2 under Article 23,Footnote 3 no significant progress has been made or can be expected in the near future.

As a result of this stalemate at the multilateral level, the strategy of the EU has been to place the protection of GIs at the heart of its intellectual property (IP) chapters in bilateral trade and investment agreements (BTIAs). In particular, Article 3(1)(e) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)Footnote 4 provides the EU with the exclusive competence to deal with common commercial policy.Footnote 5 According to Article 207(1) of the TFEU,Footnote 6 this includes commercial aspects of IP. Not surprisingly, the number of EU BTIAs is quickly growing and the EU-South KoreaFootnote 7 and EU-SingaporeFootnote 8 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), the recent Canada-EU Trade Agreement (CETA)Footnote 9 and the EU-Vietnam Trade AgreementFootnote 10 all contain annexes listing the GIs that are to be protected in the partner countries as part of the trade deal.

The nature of BTIAs, however, is that these are mixed agreements dealing with issues of tariffs and trade, but also with investment protection and, increasingly, investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS). In the context of the ongoing negotiations ISDS has become a highly controversial issue, including in the negotiation surrounding the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (TTIP).Footnote 11 The controversy lies in the fact that the policy freedom of a signatory state to an agreement containing ISDS may become limited on account of investor expectations that have to be honoured. The controversy is remarkable to the extent that ISDS has been a prominent feature in international trade and investment frameworks since the mid-1970s. In fact, the proliferation of ISDS in bilateral agreements is so widespread and affects so many trading nations globallyFootnote 12 that it is almost surprising that relatively few cases have been brought so far claiming violations under these provisions. Also regional trade agreements like the North American FTA (NAFTA)Footnote 13 and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP)Footnote 14 contain ISDS clauses.

However, the concept of ISDS is relatively new in the field of IP. This is due to the fact that IP only became a global trade issue relatively recently through the integration of IP standards and IP enforcement in the WTO framework. That said, IP is also peculiar in the sense that the valuation of IP as an object of property that can be viewed as an investment is also a relatively new concept. Even now, various approaches to valuation according to income-based, market-based and review of cost-based approaches, coupled with diverging reporting standards, yield different results.Footnote 15 Still, the number of ISDS complaints is rising and the first cases involving core issues of IP expropriation are currently pending.

Of all IP rights, the EU regime on the protection of GIs invites a substantial involvement of public authority in defining GI specifications, as well as the quality maintenance thereof. This means that any change in the specification may give rise to an investor–state dispute. This chapter charts the likelihood that GIs may become a bone of contention under constitutional expropriation protection laws, WTO disputes and ISDS, and concludes that given the nature of GI protection’s inclusion of specifications, there is a higher state involvement, and accordingly, a higher likelihood that measures negatively affecting a GI proprietor’s rights can be attributed to a state.

2 Geographical Indications and Specifications in the European Union

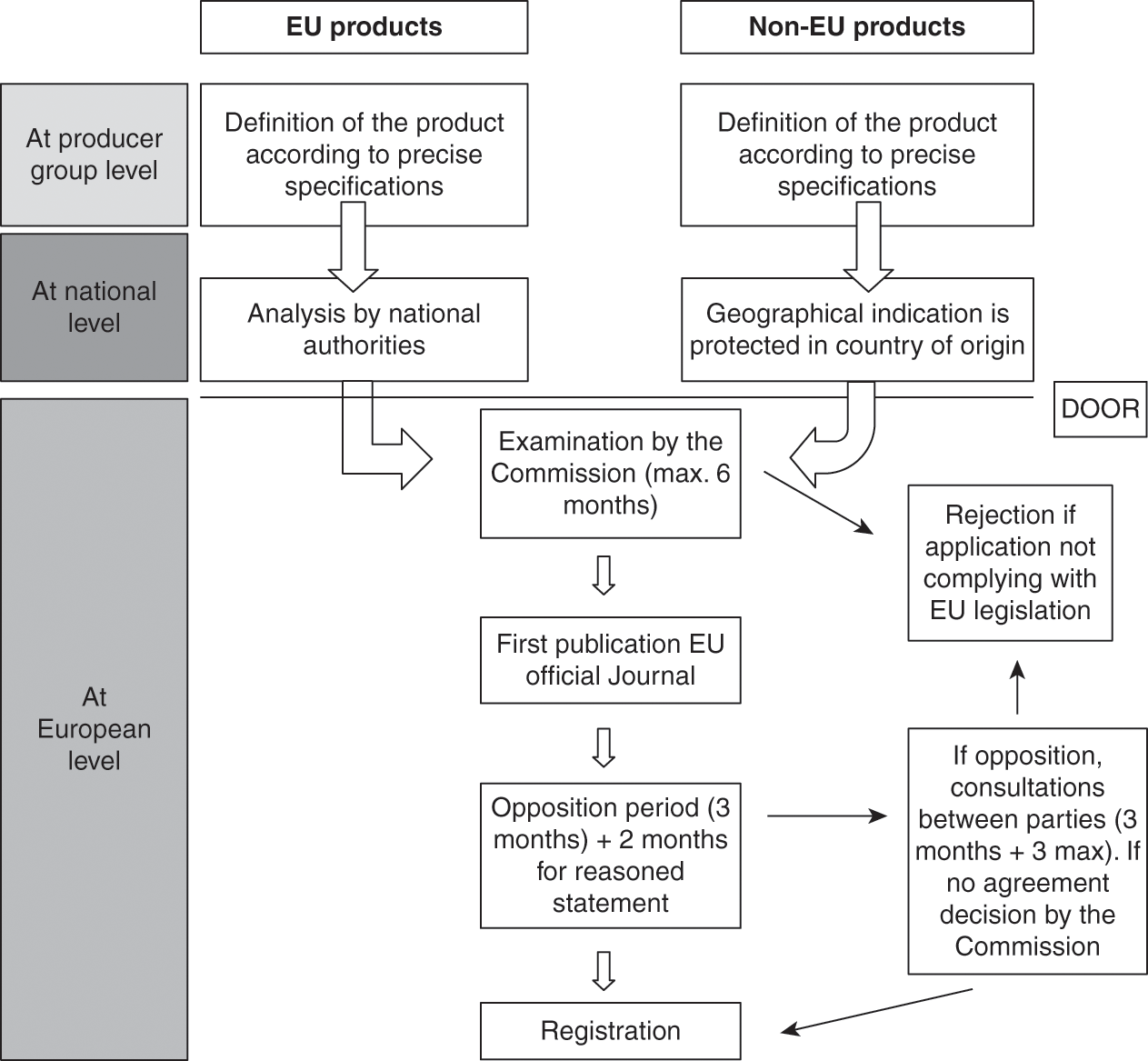

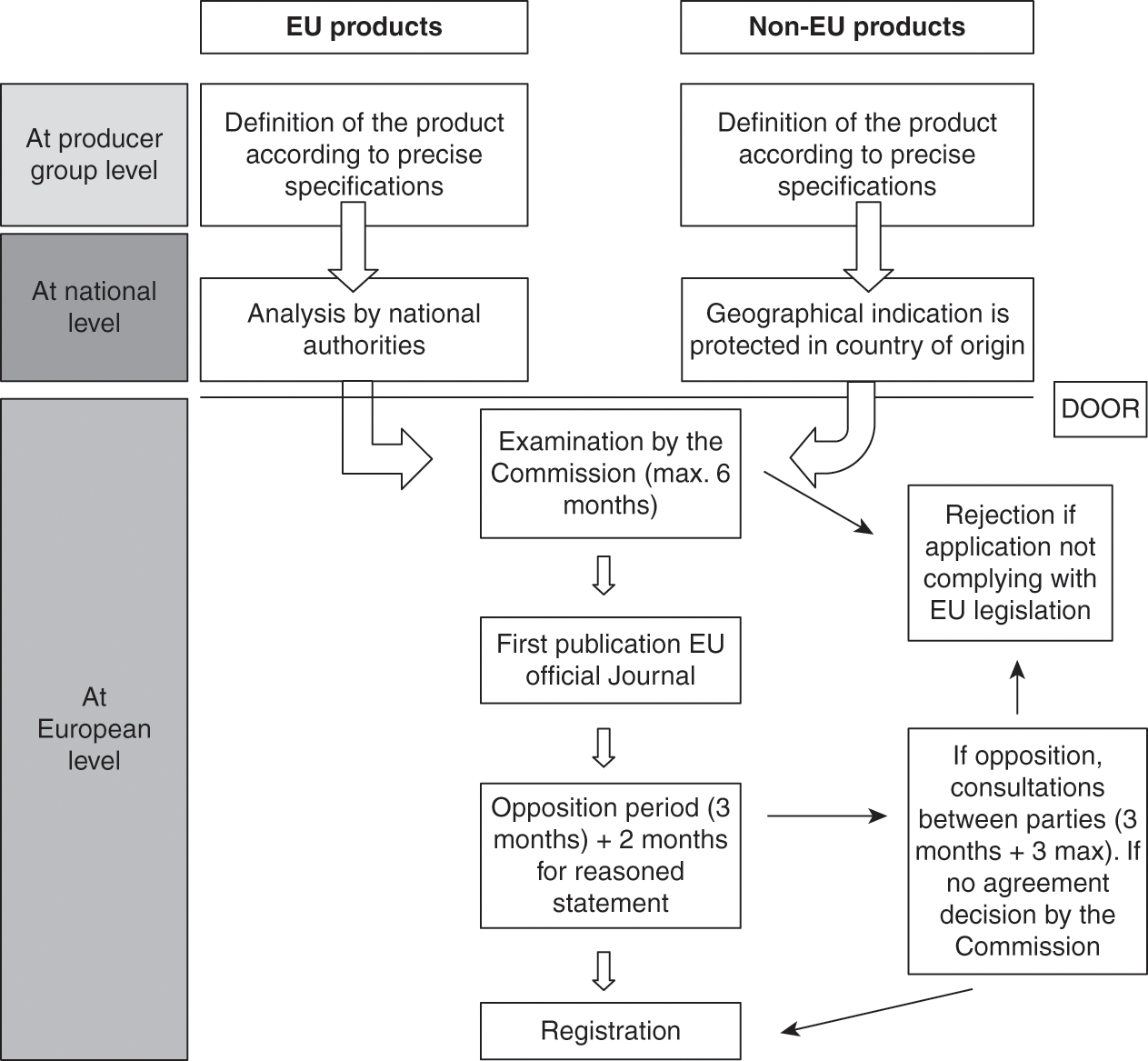

The EU PGI, PDO and TSG schemes operate on the basis of registration in the Database of Origin and Registration (DOOR).Footnote 16 There are also product-specific regimes and databases, such as the E-BACCHUSFootnote 17 for wines and E-SPIRIT DRINKSFootnote 18 for spirits. EU law also protects GIs for aromatized wine products.Footnote 19 Generally, EU law applies to products originating from EU Member States and third countries that comply with EU rules. Alongside the existing public registries, there are several certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs in the EU. These range from compliance obligations with compulsory production standards to additional voluntary requirements relating to environmental protection, animal welfare, organoleptic qualities, etc. Also, all kinds of ‘fair trade’ or ‘slave free’ epithets fall within these voluntary regimes. All these regimes should, however, be in compliance with the ‘EU best practice guidelines for voluntary certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs’,Footnote 20 in order to be in compliance with EU law.

In 2005, the United States (the US) and Australia successfully challenged the legitimacy of EC Regulation 2081/92Footnote 21 on GIs for agricultural products and foodstuffs, which was the regulation in force at the time, before the WTO. The regulation contained a number of contentious provisions, namely on (1) the equivalence and reciprocity conditions in respect of GI protection; (2) procedures requiring non-EU nationals, or persons resident or established in non-EU countries, to file an application or objection in the European Communities through their own government, but not directly with EU Member States; and (3) a requirement on third-country governments to provide a declaration that structures were in place on their territory enabling the inspection of compliance with the specifications of the GI registration. On all three points, the WTO PanelFootnote 22 found violations of Article 3(1) of TRIPSFootnote 23 and Article III(4) of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 (GATT),Footnote 24 and that the GATT violations were not justified by Article XX(d) of GATT.Footnote 25 In the Australian Report, the WTO Panel further found that these inspection structures did not constitute a ‘technical regulation’ within the meaning of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT).Footnote 26 As a result, the EU changed its regime in March 2006 to ensure compliance with the WTO regime, currently primarily through the Foodstuffs Regulation,Footnote 27 and corresponding provisions in the other Regulations.Footnote 28 The scope or protection extends to consumer deception;Footnote 29 commercial use in comparable products;Footnote 30 commercial use exploiting reputation;Footnote 31 and misuse, imitation or evocationFootnote 32 in relation to the registered GI. The enforcement of a GI is, however, a private law issue.

More interesting, for the purpose of this chapter, however, is the product specification – its establishment, inspection and enforcement – as this requires the involvement of public authority. The definition of the product according to precise specifications and its analysis by national authorities is a process integral to the registration of the GI at the EU level.

The definition of the product comprises the following elements: the product name, applicant details, product class, the name of the product, the description of the product, a definition of the geographical area, proof of the product’s origin, a description of the method of production, the linkage between the product and the area, the nomination of an inspection body and labelling information.Footnote 33 For PDOs, all production steps must take place within the geographical area, whereas for PGIs at least one production step must take place within the geographical area. It is also at this point where specific rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging and the like of the product to which the registered name refers may be stated and justified. Given the fact that these types of conditions on repackaging or slicing result in geographical restrictions having strong protectionist and anticompetitive effects, they are among the most controversial specifications.

In 1997, the Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma,Footnote 34 the Italian trade association of 200 traditional producers of Parma Ham, sought injunctions against Asda Stores in the United Kingdom to restrain them from selling pre-sliced packets of prosciutto as ‘Parma Ham’, a protected PDO. The ham was sliced by a supplier of Asda outside the production region, and pre-packaged without supervision by the inspection body responsible for enforcing EU production regulations. The slicing of the ham itself cannot be problematic as such,Footnote 35 but the question is whether slicing the ham away from the consumer’s eyes and offering them as a pre-packaged product not bearing the Consorzio’s mark would be infringing upon the PDO. The Consorzio’s argument was that the consumer could not verify the origin, and the quality of the ham could not be guaranteed. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEUFootnote 36) heldFootnote 37 that protection conferred by a PDO did not normally extend to operations such as grating, slicing and packaging the product. The CJEU, however, stated that those operations were prohibited to third parties outside the region of production only if they were expressly laid down in the specification, and if this condition was brought to the attention of economic operators by adequate publicity in Community legislation. The latter was not yet the case under the old regime.Footnote 38 Under Article 8.2Footnote 39 of Regulation 1151/2012, the product specification is now to be included in the single document that is contained in the DOOR register, and the Consorzio can now enforce its slicing and packaging rules.

The specification also contains the names of the inspection bodies responsible for enforcing EU production regulations.Footnote 40 In each Member State, public authorities or government agencies are entrusted with this task. When it comes to defining or redefining the specification, however, quite a lot of state involvement can be observed. A case on point is the enlargement in 2009, actively supported by the Italian government, of the area of production for ‘Italian Prosecco’.Footnote 41 The production of this sparkling wine has been traditionally confined to the Veneto Region around Venice, but it was suddenly ‘strategically’ expanded to include the town of Prosecco, which is located in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region near Trieste and the Slovenian border. This is the place where the Prosecco grape variety is believed to have originated from. Yet, upon accession to the EU in 2013, Croatia found that its sweet Prošek dessert wine, which is different from Italian Prosecco in all aspects of methods of production and grapes used, could no longer coexist in the EU with Italian Prosecco.Footnote 42

In short, GIs are peculiar in the sense that they constitute a type of IP right where a lot of state involvement can be observed, especially in the drafting, maintenance and alteration of the GI’s specification. This may lead to the consortium of GI producers, or the (semi-)state authority itself to alter a GI specification after the GI has been registered. As a consequence, this may give rise to investor–state disputes by private parties that may consider themselves affected by these changes or the recognition of GIs in general (in that they may no longer be able to market their products under the same or similar names), since many of these measures leading to the definition of the GI’s specification can be directly or indirectly attributed to the state.

3 Geographical Indications as Property

Like other IP rights, GIs are protected as proprietary interests. This becomes apparent from the WTO Panel report in EC – Trademarks and Geographical Indications,Footnote 43 but even more so in the context of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In the case of Anheuser-Busch v. Portugal, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) held that the protection provided for by Article 1 of the Protocol No.1 to the ECHR,Footnote 44 which guarantees the right to property,Footnote 45 is applicable to IP as such.Footnote 46 This means that the owner of an intellectual ‘possession’ is protected in respect of (1) the peaceful enjoyment of property; (2) deprivation of possessions and the conditions thereto; and (3) the control of the use of property by the state in accordance with general interest. Inherent in the convention is the recognition that a fair balance needs to be struck between the demands of the general interests of society and the requirements of the protection of the individual’s fundamental rights.Footnote 47

Since 2000 the EU Charter on the Protection of Fundamental Human RightsFootnote 48 recognized similar principles that EU citizens can rely on. In Scarlet Extended v. Sabam,Footnote 49 the CJEU held:

The protection of the right to intellectual property is indeed enshrined in Article 17(2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘the Charter’). There is, however, nothing whatsoever in the wording of that provision or in the Court’s case-law to suggest that that right is inviolable and must for that reason be absolutely protected … The protection of the fundamental right to property, which includes the rights linked to intellectual property, must be balanced against the protection of other fundamental rights.

Opinions on how this balance should be struck, however, naturally differ, depending on one’s perspective. In a European case, British American Tobacco,Footnote 50 involving challenges to restrictions on advertising, branding and trademark communication in relation to tobacco products, the CJEU held that restrictions on trademark use requiring labels to display health warnings by taking up 30 per cent of the front and 40 per cent of the back of a cigarette packageFootnote 51 amount to a legitimate restriction that still allows for a normal use of the trademark. The tobacco companies had argued that there is a de facto expropriation of their property in the trademark. A similar argument was made in the well-publicized constitutional challenge case to the Australian Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011.Footnote 52 The High Court of Australia in BAT v. Commonwealth of AustraliaFootnote 53 held that there was no acquisition of property that would have required so-called ‘just terms’ protection under the Australian constitution. Yet it is the Australian Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 that has also produced two WTO challenges to tobacco plain packaging, by UkraineFootnote 54 and by a number of other states.Footnote 55 Although Ukraine suspended its proceedings on 28 May 2015, the litigation by Honduras, Cuba, Indonesia and the Dominican Republic remains unaffected. Plain packaging also sparked investor–state disputes.Footnote 56 These cases raise questions on the remaining policy freedom that nation states have in regulating the use or exercise of IP in light of societal interests, such as public health, in the context of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements, and investment protection agreements.

4 Investor–State Dispute Settlement and WTO Law

Bilateral free trade and investment agreements may provide additional protection to investors in relation to their investments that are then considered to be ‘possessions’ in the state where such investments have been made. The question is then to what extent protection granted by means of bilateral agreements changes the legal relations between WTO Members. Although the annexes to EU BTIAs list GIs that are to be protected under the agreement,Footnote 57 it remains to be examined what their effect under the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) is.

The WTO Appellate Body, in Mexico – Taxes on Soft Drinks,Footnote 58 rejected the notion that parties can modify WTO obligations by means of an FTA, whereas the WTO Panel in Peru – Additional DutyFootnote 59 was not so categorically opposed. In the latter case, there are numerous references to Peru’s freedom to maintain a price range system (PRS) under an FTA with complainant Guatemala. The WTO Panel, however, observed that the FTA in question was not yet in force, and that its provisions should therefore have limited legal effects on the dispute at hand. Peru’s arguments in respect of the FTA were that, even assuming that Peru’s PRS was WTO-inconsistent, Peru and Guatemala had modified between themselves the relevant WTO provisions to the extent that the FTA allowed Peru to maintain the PRS. Upon appeal, the Appellate Body stated:

[W]e are of the view that the consideration of provisions of an FTA for the purpose of determining whether a Member has complied with its WTO obligations involves legal characterizations that fall within the scope of appellate review under Article 17.6 of the DSU.Footnote 60

However, it also considered that WTO Members cannot modify WTO provisions such that these become WTO-inconsistent, even if these changes ‘merely’ operate bilaterally inter partes and not amongst all WTO Members. In particular, the Appellate Body held:

We note, however, that Peru has not yet ratified the FTA. In this respect, it is not clear whether Peru can be considered as a ‘party’ to the FTA. Moreover, we express reservations as to whether the provisions of the FTA (in particular paragraph 9 of Annex 2.3), which could arguably be construed as to allow Peru to maintain the PRS in its bilateral relations with Guatemala, can be used under Article 31(3) of the Vienna Convention in establishing the common intention of WTO Members underlying the provisions of Article 4.2 of the Agreement on Agriculture and Article II:1(b) of the GATT 1994. In our view, such an approach would suggest that WTO provisions can be interpreted differently, depending on the Members to which they apply and on their rights and obligations under an FTA to which they are parties.Footnote 61

In the case at hand, this means that Peru under the FTA is only allowed to maintain a WTO-consistent PRS, which should meet the requirements of Article XXIVFootnote 62 of the GATT 1994, which permits certain specific deviations from WTO rules. All such departures require that the level of duties and other regulations of commerce applicable in each of the FTA members to the trade of non-FTA members shall not be higher or more restrictive than those applicable prior to the formation of the FTA.Footnote 63

In Turkey – Textiles,Footnote 64 the Appellate Body held that the justification for measures that are inconsistent with certain GATT 1994 provisions requires the party claiming the benefit of the defence provided for by Article XXIV GATT 1994 lies in closer integration between the economies of the countries party to such an agreement. It is clear that Peru’s PRS measure cannot be interpreted as a measure fostering closer integration; rather, it results in the opposite. The GI ‘claw-back’ annexes to EU BTIAs can arguably be held to contain obligations that approximate the economies of the parties to the agreement, providing the holder of such a GI legal certainty not only as to the protection and enforcement of the GI but also as to the protection of an ‘investment’ in terms of production and marketing of a GI product.

The WTO Dispute Settlement Body has meanwhile established dispute settlement panels in relation to Australia’s tobacco plain packaging measure. GIs are part of the property package on which the claim is based. The five complainants are arguing that the measure is inconsistent with Australia’s WTO obligations under TRIPS,Footnote 65 TBTFootnote 66 and the GATT 1994.Footnote 67 In respect of trademarks and GIs, the claim is that restrictions on their use amount to an expropriation of property. There is only one caveat that will be of relevance to a decision in these casesFootnote 68 in the context of TRIPS, and that is that in EC – Geographical Indications, the panel held:

[T]he TRIPS Agreement does not generally provide for the grant of positive rights to exploit or use certain subject matter, but rather provides for the grant of negative rights to prevent certain acts. This fundamental feature of intellectual property protection inherently grants Members freedom to pursue legitimate public policy objectives since many measures to attain those public policy objectives lie outside the scope of intellectual property rights and do not require an exception under the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 69

5 Investor–State Dispute Settlement and Geographical Indications

The ISDS case of Philip Morris Asia v. AustraliaFootnote 70 shows that investor–state disputes can be brought in support of, or as an alternative to, constitutional and WTO challenges. In this case, Philip Morris Asia challenged the tobacco plain packaging legislation under the 1993 Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of Hong Kong for the Promotion and Protection of Investments. The arbitration was conducted under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Arbitration Rules 2010.Footnote 71 In a decision of 18 December 2015, the Tribunal hearing the case ruled that it had no jurisdiction to hear Philip Morris Asia’s claim.

However, it is important to realize that the proliferation of ISDS clauses in bilateral trade agreements is increasing. Investor–state dispute settlement revolves around the question of whether expropriation, directly or indirectly, has been conducted according to the principles of Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET). FET is determined through applying principles of (1) reasonableness, (2) consistency, (3) non-discrimination, (4) transparency and (5) due process. In this context, the legitimate expectations of an investor are taken into consideration in order to assess whether the state has expropriated in bad faith, through coercion, by means of threats or harassment. Due to the fact that there is no true harmonized multilateral dispute settlement system in relation to investment disputes, the interpretation and application of these principles are not uniform. Due to the confidential nature of arbitration, not all arbitration reports are public. The most concrete expressions of what legitimate investor expectations are can be found in statements made in published cases that seem to indicate that a balance must be struck.

For example, in International Thunderbird v. Mexico,Footnote 72 a NAFTA dispute conducted under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the panel held:

[A] situation where a Contracting Party’s conduct creates reasonable and justifiable expectations on the part of an investor (or investment) to act in reliance on said conduct, such that a failure by the NAFTA Party to honour those expectations could cause the investor (or investment) to suffer damages.Footnote 73

Conversely, in Saluka v. Czech Republic,Footnote 74 an investor–state dispute also conducted under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the panel held:

No investor may reasonably expect that the circumstances prevailing at the time the investment is made remain totally unchanged. In order to determine whether frustration of the foreign investor’s expectations was justified and reasonable, the host State’s legitimate right subsequently to regulate domestic matters in the public interest must be taken into consideration as well.Footnote 75

There are few ISDS cases involving IP.Footnote 76 These are cases that have been argued under the rules of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which is an independent branch of the World Bank.

First, there was a failed attempt at arguing a trademark infringement case under investor–state dispute settlement in AHS v. Niger.Footnote 77 In this case, although a concession to service Niger’s national airport had been terminated, there was continued use of seized equipment and uniforms bearing the trademarks of the complainant. The panel held that it had no jurisdiction, as IP enforcement is a civil matter that cannot be raised in the context of the ISDS expropriation complaint.

Second, there is the ongoing case of Philip Morris v. UruguayFootnote 78 that is argued under the Uruguay-Switzerland FTA,Footnote 79 and where the legitimacy of plain packaging tobacco products is challenged. In this case jurisdiction has been established and proceedings on the merits are to follow.

Third, there is a NAFTAFootnote 80 case argued under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. In Eli Lilly v. Canada,Footnote 81 pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly sought damages for $100 million CAD and challenged changes to the patentability requirements in respect of utility or industrial applicability, leading the Canadian patent office to invalidate two of Eli Lilly’s patents for the Strattera attention-deficit disorder pill and the Zyprexa antipsychotic treatment. Eli Lilly argued that the interpretation of the term ‘useful’ in the Canadian Patent Act by the Canadian courts led to an unjustified expropriation and a violation of Canada’s obligations under NAFTA on the basis that it is arbitrary and discriminatory. Canada conversely argued that Eli Lilly’s claims were beyond the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. Ultimately, in March 2017, the Tribunal dismissed Eli Lilly’s claims and confirmed that Canada was in compliance with its NAFTA obligations.Footnote 82

Cases involving IP can be and are clearly brought if measures negatively impacting upon the ‘investment’ can be attributed to a state that has submitted to ISDS. Issues such as IP enforcement or thresholds for patentability as such appear to be outside of the remit of ISDS, as these are civil or administrative matters where access to judicial review is usually provided. However, complaints over (arbitrary or discriminatory) denial of justice may not be. In the cases described above, one can argue that the general measures taken are neither of an arbitrary nor discriminatory nature. GI specifications, on the other hand, are discriminatory by nature since they are always specifically targeted, and this characteristic exceeds the already exclusionary nature of an IP right. This is because, as we have seen, the definition of the product comprises not only the product name and related labelling but also the description of the product, a definition of the geographical area, proof of the product’s origin, a description of the method of production, the linkage between the product and the area, the nomination of an inspection body empowered to police the specification.

This means that there are a number of actions that may have an immediate impact, not only on the existence and exercise of a GI, but also on its value and costs. The example of the Italian Prosecco DOC reformFootnote 83 comes to mind, as an enlargement of the geographical area, but also a possible reduction thereof has immediate effects for producers within and outside of the area. Production methods may also be subject to changes. Changes to production requirements resulting from a raise in food safety standards may be legitimized within the context of the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS).Footnote 84 Many of the GI production requirements are, however, steeped in a tradition and culture that solicit the demand for a particular product. If one, for example, orders Limburg Grotto Cheese,Footnote 85 one expects the cheese to have been ripened through completely natural processes by exposure of the cheese to the atmosphere of a limestone cave that contains the Brevibacterium Linens that produces a cheese with a pungent odour. The cheeses ripen on oak wooden boards and need to be turned regularly. This is a delicate operation as the fungi growing on the cheeses are poisonous. The result of food safety standards (no oak, stainless steel racks, etc.) has been that the traditional production for the traditional connoisseur consumer has now moved literally and figuratively underground. As a result, only the more industrial producers remain around to sell a product that is compliant with legal standards. They are selling a product that may be safer (although this is often disputed) but is certainly far less traditional than the consumer is led to believe. Phasing-out rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging, etc. stem from a desire to free the market from anticompetitive restrictions, but arguably these could also be measures that have a negative impact on the investments made by producers benefitting from GI specifications containing such rules. These forms of proprietary protection of GIs via individual regulations are also open to non-European entities, as we have seen above. So, a US association that holds an EU GI, such as the Idaho Potato Commission,Footnote 86 could then also sue before the special ISDS courts envisaged under the TTIPFootnote 87 for a weakening or strengthening of protection standards in Europe. In most cases, after all, the measure can be attributed to the state, and despite attempts by EU Member States to deny private parties the right to invoke international treaties, the CJEU has affirmed the direct effect of international treaties that bind the EU.Footnote 88

6 Conclusion

More than any other IP, a GI displays a very high level of state involvement in relation to specifications that do not directly concern the exercise of the IP right in terms of protection against consumer confusion and the like, but that very much influences the value of the GI for its owner. Definitions of territory, methods of production, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, and other more nefarious rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging, etc. can be changed at the behest of members of the consortium, but also of (semi-)state authorities or agencies. Insofar as these lead to a negative impact on members of the consortium, or third parties, there appears to be an increase in the options to challenge such measures under domestic constitutional and WTO rules, or bilateral and regional trade and investment agreements containing ISDS. These ISDS clauses are commonly included in recent US and EU trade and investment agreements, also those with Asian partners. To date, only a limited number of such cases that have been brought involve IP rights. The likelihood of success appears limited, but several key cases are still pending. In ISDS complaints over IP enforcement, tribunals seem hesitant to accept jurisdiction over these cases. In the plain packaging tobacco cases, the question will be the extent to which WTO Members have policy freedom in articulating exceptions to WTO obligations.

EU GI specifications are very targeted and individual in nature, so that any measure affecting them may be considered arbitrary or discriminatory much more easily as compared to general policy measures affecting the use, grant or scope of a trademark, design, copyright or patent right. Furthermore, many specifications are rooted in culture and custom rather than in science and utility, which raises the chances of a dispute over arbitrariness and discrimination in standards imposed when determining issues of culture and custom. Finally, measures affecting GI specifications are often attributable to a public authority or agency. This combination increases the likelihood of success of claims for protection of GIs as property and investments. If, for example, an EU company takes over (i.e., invests) a business located in Vietnam or Korea that is involved in the production of a GI product, and the Vietnamese or Korean authority redefines the geographical area in such a way that the EU company can no longer use that GI, this could give rise to an ISDS case. The same could be true for a US company making investments in Asian jurisdictions. This should be taken into consideration when drafting or changing GI product specifications.