Introduction

This case study focuses on smart tech deployment and governance in Philadelphia. In 2019, the City of Philadelphia launched a new smart city initiative, SmartCityPHL. SmartCityPHL includes a roadmap of strategies, processes, and plans for deployment. In many ways, the new initiative is remarkable. It is ambitious yet pragmatic; it outlines a set of guiding principles along with deliberative and participatory processes; it is broadly inclusive of people and values – as reflected in its simple definition of a smart city: “a city that uses integrated information and communication technology to support the economic, social, and environmental goals of its community.” On its face, and perhaps in comparison with other smart city initiatives, SmartCityPHL provides an exciting roadmap. But the 2019 initiative was not the first smart city project in Philadelphia. There is, in fact, a long history of Philadelphians turning to supposedly smart technology to solve community problems.

As with many smart city case studies, it is difficult to choose a starting date or focal point to study. After all, Philadelphia has long relied on data and technology in many different sectors, ranging from education to policing to traffic management. A longitudinal history across many sectors and decades would tell a fascinating story that could fill volumes. We will not dig that deeply or widely, however. Instead, we choose two nested “action arenas” as focal points.

First, we examine the macro-level action arena, which concerns city-wide governance of smart tech deployment, reflected in the set of smart city initiatives culminating in the current SmartCityPHL program. We briefly outline the descriptive characteristics of this action arena, and then we discuss the imagined and actual pictures of Philadelphia as a smart city from 2011 to 2016 and compare them with what has emerged over the past five years. This comparative analysis usefully highlights different applications of smart tech and conceptions of the smart city as well as evolving norms, goals, strategies, and governance.

Second, we examine one meso-level action arena, which concerns city-wide governance of vacant property management. In this context, smart tech deployment plays varied roles. We first describe a complex array of historical and contextual factors that shape the vacant property crisis in Philadelphia, and then we focus on stakeholders, knowledge problems, and potential smart tech solutions. We explore some useful implementations of smart tech, primarily data sharing and mapping tools. We also identify a series of governance challenges, including some concerning political structure, coordination of organizational responsibilities, and community inclusion.

Methodology

For both action arenas, we examine smart tech deployment and governance. Our primary aim is description, not normative or empirical outcome evaluation. We used the GKC framework, described in Chapter 1, to structure our mixed methods research.

The team reviewed dozens of publications, including academic articles, government reports, industry papers, newspaper articles, and websites. As is further described in the Appendix, we used a content analysis process to review these documents. Along with our team of research assistants, we developed a coding system based on the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework and relevant subject matter topics. The assistants coded the documents, and we used AtlasTI, a software program, to organize and analyze the data. The team then developed reports and charts describing the frequency of key concepts. The Appendix contains additional detail regarding the coding process, as well as summary charts.

After a protocol review by the Villanova University IRB, we conducted twelve semi-structured interviews with professionals directly involved in smart tech deployment in Philadelphia. We used the GKC framework to provide structure and generate interview questions. We recorded, transcribed, and summarized the interviews, which averaged sixty-four minutes. The research assistant team then coded the content of these interviews using the same process outlined above. Finally, we integrated the background and interview information in our main findings outlined in this chapter. Prior to publication, we used a member checking process to ensure accuracy of the interview citations and quotes; we shared the draft study with interviewees for review and additional feedback.

Background Context

To situate our discussion of Philadelphia’s smart city approaches, we briefly describe some of background facts concerns the social, economic, and political context (Table 5.1). With a population of nearly 1.6 million (US Census QuickFacts Philadelphia 2021),Footnote 1 Philadelphia is America’s sixth largest city, recently dropping one ranking behind Phoenix (Castronuovo Reference Castronuovo2021). Philadelphia’s population is among the poorest of any major US city, second only to Detroit (Statista 2022). The city also has relatively low levels of educational attainment and workforce participation and a relatively high unemployment rate, connecting to a median household income that is nearly $16,000 less than the national median (US Census QuickFacts Philadelphia 2021; US Census QuickFacts United States 2021; St. Louis Federal Reserve 2022). Philadelphia is home to nearly 700,000 employed persons and its major industries are healthcare and education (33 percent of employment), government (14 percent), and professional and business services (15 percent) (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2022). Of the total Philadelphia jobs, nearly 100,000 are in the service sector, which on average in Philadelphia pays $10.71 per hour (Harknett and Schneider Reference Harknett and Schneider2018).

Table 5.1. Socioeconomic background Philadelphia

| Philadelphia | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (July 2021) | 1,576,251 | 331,893,745 |

| Proportion without high school degree | 14.3% | 11.5% |

| Proportion in labor force | 61.5% | 63% |

| Median household income | $49,127 | $64,994 |

| Unemployment level (Dec. 2021) | 6.3% | 3.9% |

| Persons in poverty | 23.1% | 11.6% |

| Proportion with a computer | 88.5% | 91.9% |

| Proportion with broadband subscription | 80.5% | 85.2% |

Likely due at least in part to its economic challenges, the citizens of Philadelphia generally have reduced access to computers and the internet when compared to the nation overall. The percentage of households with a computer is 3 points lower than the nation and is lower than many other major American cities such as Houston (91.5 percent), Phoenix (93.8 percent), New York (90.8 percent), or Chicago (90.4 percent) (US Census QuickFacts: Houston 2021, Phoenix 2021, New York 2021, Chicago 2021). Philadelphians also have reduced access to the internet, with a little less than 20 percent of its population lacking a broadband subscription, again lower than the nation and the other major US cities previously mentioned (US Census QuickFacts Philadelphia, Houston, Phoenix, New York, Chicago, United States 2021).

The City of Philadelphia is governed by a home rule charter first adopted in 1951. This type of governance allows the city to have direct control over all municipal matters not explicitly denied by the state constitution, rather than the more traditional model where municipalities are only allowed to act in ways expressly provided for by the state. The home rule model has given the City incredible flexibility in governing its citizens and wide discretion to adopt new technologies to solve problems. Philadelphia functions as a consolidated city and county government. It is considered a mayor–council form of government, with separate elections for each of these types of political leadership (National League of Cities n.d.). The Philadelphia City Council plays a significant role in local public policies.Footnote 2

Smart City Planning and Governance (Macro-Level Action Arena)

Philadelphia has always used technology to solve problems, provide public services, and otherwise manage its affairs. Over the past few decades, the city’s approach to deploying supposedly smart technologies and becoming a “smart city” has evolved. For this study, we examine how the City of Philadelphia has approached smart tech deployment over the past decade. City planning is a complex topic. The politics alone are daunting. To avoid getting mired in those details, we maintain focus on the city’s evolving strategic plans, practices, and governance for using “smart tech” to improve public services and achieve other community objectives, including becoming a twenty-first-century smart city.

At the macro-level of city-wide planning and governance, there is an incredibly wide range of shared resources, but the most important for the purposes of our study appear to be expertise, political capital, shared commitments and values, various types and collections of data (including personal information), and various forms of information technology (IT), sensors, communications networks, and other components of smart tech. Although not sharable because it is rivalrous, financial capital is also important because its allocation is a significant indicator of priority. We discuss specific shared resources in more detail in the sections that follow.

Community members can be described very broadly, but with respect to city planning and governance, we can differentiate the entire Philadelphia community from smaller subgroups directly involved with and affected by city planning. We can distinguish government, industry, academic, and citizen groups. Within those groups, we can draw further distinctions based on political, socioeconomic, instrumental (e.g., job function), or other characteristics. For example, for government, we can differentiate elected officials, departments, bureaucrats, and various government employees and contractors providing public services. At this level of abstraction, it might not be useful to delineate community members. We discuss community members further in the sections that follow.

At the macro-level, laws, regulations, policies, and norms all play a role in governance. Politics and public opinion also play important roles. For smart tech, procurement and privacy policies supply basic rules-in-use, some of which we discuss below. We discuss two additional sources – a series of Executive Orders and the SmartCityPHL Roadmap.

Smart City Planning and Governance: 2011–2016

In Philadelphia, the smart city imagined around 2011 was optimistic and familiar, essentially what was pitched in so many marketing materials and TED talks. Mayor Michael Nutter championed smart tech and the idea of Philadelphia becoming a smart city, both to solve local problems and to compete globally. In speeches, such as his 2012 keynote speech at IBM’s Smarter Cities Summit, Nutter incorporated “a common rhetorical theme in the … presentation of Philadelphia as a smart city, a theme enrolled in an ongoing, entrepreneurial economic growth agenda that oriented the city towards globalized enterprise” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 537). Themes of modernization and technological advancement permeated the rhetoric surrounding Philadelphia’s smart city initiatives. Creating a “[p]erception of Philadelphia as an innovative place with a dynamic economy was crucial to maintaining forward momentum to turn the city into a vibrant node in the globalized economy, instead of a failed, nineteenth and twentieth century industrial power” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 548).

The mayor’s ambitious agenda was exemplified by two distinct and very different agenda items (meso-level action arenas worthy of more detailed, independent study): the city’s engagement with IBM on the Digital On-Ramps project, and a series of Executive Orders issued by the Mayor’s Office.

Digital On-Ramps

Like many cities, Philadelphia has faced and still faces major obstacles in delivering educational and workforce training services to its citizens (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 541). It is a rather complex social problem. Could smart tech be the solution?

In 2011, Philadelphia was one of twenty-four cities chosen to receive a Smarter Cities Challenge grant from IBM. This IBM reward led to a direct consultation. A team of IBM experts spent a few weeks working on a report that delivered recommendations on how the city could use smart tech to increase literacy and improve employment opportunities in Philadelphia. The solution IBM recommended, and advised on, was Digital On-Ramps (DOR) (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 536).Footnote 3 DOR was “a workforce education portal that would link unemployed or underemployed residents to online, easily accessible training modules for work in emerging industries of the globalized economy” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 540). According to IBM’s Smarter Cities Challenge Report, “[DOR] will provide Philadelphians with a framework for delivering comprehensive education and workforce training to youth and adults, using a blended learning approach” (IBM 2011, 4). The initiative was a part of an “ongoing, entrepreneurial economic growth agenda that oriented the city towards globalized enterprise” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 536). Incorporating familiar “rhetoric of the smart city, wireless, ubiquitous computing offered the potential to connect residents to digitized information that could take the place of civic services formerly found in physical locations, [in this case,] to move educational services from schools and community centers to a digital application” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 541). The DOR program sought to create

one of the largest and most effective citywide human capital management systems in the United States. The vision for DOR is that it will allow citizens to access education, training and support to assist them in developing literacy, digital literacy and workplace skills. The ultimate goal is to put unemployed citizens back to work, and help employed people advance to better paying jobs and careers.

Could an online portal and smartphone app deliver these services and meet the ambitious goals set by IBM and the Nutter administration?

No, at least not at that time.Footnote 4 “[A] workforce education application could never, on its own, provide pathways for jobs for the 500,000 the Mayor claimed were in need of new skills” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 548). Nutter praised the initiative in his 2012 speech as if it had already been successful, but it had “neither recruited a single participant nor secured a job for anyone” (Wiig Reference Wiig2016, 536). According to Shelton, Zook, and Wiig (Reference Shelton, Zook and Wiig2015, 21), the DOR was driven mostly by hype, and “the smart city … acted primarily as a promotional vehicle.” The potential of the program to spark a substantial “change to the endemic poverty, marginalization, and social polarization in Philadelphia was present, but the smart city discourse relied too much on the possibility of new industries locating in Philadelphia in the near future because of the presence of a trained workforce, rather than on providing jobs for residents in need” (Wiig Reference Shelton, Zook and Wiig2015, 536).Footnote 5

One might say that IBM and others sold “tech solutionism” (Morozov Reference Morozov2013), and Philadelphia, at least Mayor Nutter, bought it.

A more charitable interpretation of the events is that the Nutter administration submitted a grant proposal, received a grant, ran a pilot, and learned that the smart tech intervention was not enough. As we discuss later, perceptions and expectations about smart tech varied among community members and have evolved with this and other experiences. However one interprets the DOR story, our study strongly suggests that community members learned and adapted their expectations (as will be discussed).

Smart Tech Planning and Governance via Executive Order

Alongside the DOR project, Mayor Nutter adopted a pragmatic governance approach rooted in conventional public administration.Footnote 6 He issued a series of Executive Orders, which set goals, clarified responsibilities, provided direction, generated positions and working groups, and paved the way for smart tech deployment and data sharing in Philadelphia.

Mayor Nutter’s Executive OrdersFootnote 7 have their roots in EO 11-93 issued September 15, 1993 by Mayor Rendell. That order established the Mayor’s Office of Information Services (MOIS), which had the responsibilities of:

(1) establishing a strategic information technology plan, (2) establishing an IT steering committee to support strategic changes across the city, (3) to perform the needed assessment, development, operations, and maintenance of information systems applications across the city, and (4) establishing and operating an end user information center to provide re-engineering assistance and training in City standard IT policies.

The MOIS lasted until May 28, 2008, when Mayor Nutter signed EO 08-08, which established the Division of Technology (DOT). EO 08-08 focused on bringing Philadelphia into the digital era through the establishment of key positions and committees to oversee technology-based decisions. On July 6, 2009, Mayor Nutter signed EO 06-09, which effectively restated EO 08-08 with more explanation of various roles and responsibilities.

On August 22, 2011, Mayor Nutter signed EO 12-11, which took the existing DOT and restructured it into the Office of Innovation and Technology (OIT). OIT had the same responsibilities as the DOT, modified with language concerning interdepartmental cooperation and communication. EO 12-11 remains the guiding order on the structure and goals of OIT, which includes bridging the use of technology and information systems across city departments. EO 12-11 requires OIT to manage “[(1)] City telecommunications and information technology contracts, competitive bids, and requests for proposals … [(2)] establish information security policies … [and (3)] establish a Five-Year Strategic and Financial Plan defining … policies, procedures, processes, [and] guidelines … for Citywide telecommunications and information technology operation” (Executive Order 12-11, Information Technology, of August 22, 2011). The new OIT included several key positions and bodies including the Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), and the Technology Advisory Committee (TAC). The CIO serves as the head of the OIT and is responsible for managing the city’s technology and information systems as well as software acquisitions. The TAC serves to “provide strategic advice and counsel to the Office of Innovation and Technology and the CIO” (Executive Order 12-11, 4) It is comprised of thirteen people including the Managing Director, who serves as Philadelphia’s Chief Operating Officer, the Mayor’s Chief of Staff, the Finance Director, the Budget Director, the City Solicitor, the CIO, and several deputy mayors of various departments throughout the city.

Working in tandem with EO 12-11, chapter 21-2500Footnote 8 of the Philadelphia Code and Home Rule Charter requires that the Managing Director of the TAC produce and submit an annual information technology strategic plan to city council. According to the ordinance, the plan must “summarize and evaluate the current state of the City’s telecommunications and information technology infrastructure and detail and analyze the costs and benefits of the City’s plans for the acquisition, management, and use of telecommunications and information technology over the next five fiscal years” (Philadelphia Home Rule Charter § 21-2502).

On April 26, 2012, Mayor Nutter signed EO 1-12, which introduced five main goals for the City of Philadelphia concerning data use and transparency: the formation of an open data working group, the governance of data by an advisory board, an open government plan, an open data policy, and a social media policy. These five sections created policies and positions for administrators to do work involving data that has subsequently shaped Philadelphia’s data policies and plans over the last several years, including the SmartCityPHL Roadmap, which we discuss below. Notably, EO 1-12 established the Chief Data Officer (CDO), who is responsible for spearheading the open data initiative for the city.

EO 1-12 established an Open Data Policy in Philadelphia. The policy has eight main components, including the establishment of an Open Government Portal for sharing information related to the Executive Order, the establishment of an Open Data Catalog where each department in the city is required to catalog their data to determine if it needs to be shared in the Open Government Portal. The order also made clear the need for city departments to announce a timeline for the release of their data, the desire for public feedback as a mechanism for citizens to request data or share input about what information should be published, the identification of high-value datasets, and a six-month evaluation of the city’s progress toward fulfilling the open data initiative laid out in the Executive Order.

EO 1-12 directly led to the publishing of various governance documents articulating the city’s position on data collection and use as well as recommendations for how departments can share data either with each other or with the public. For example, as a result of EO 1-12, the City of Philadelphia published an Open Government Plan (GitHub 2013), which included themes of transparency, public participation, and collaboration.

The CIO and the CDO also published the Open Data Guidebook for city agencies. It describes best practices for preparing and sharing data across city departments and with the general public. The guidebook includes requirements for data structure to be compatible with the city’s metadata catalog, which is a repository for descriptive information concerning published datasets. The guidebook also supplies a methodology and reasoning for why publishing data is helpful for a city government:

By releasing open data, city departments may help to stimulate new and innovative ideas from our local technology community. There is great potential for open data to act as the fuel for new solutions and even new businesses that can address common problems or challenges facing those that live in, work in or travel to the City of Philadelphia.

EO 1-12 also led to collaboration with OpenDataPhilly, which is a private initiative managed by software firm Azavea. OpenDataPhilly is an online portal where people can request or publish datasets. The Open Data Guidebook specifies OpenDataPhilly as a place for city data to be published, after release by the CDO.

The Data Services Team within OIT provides a citywide data inventory online that describes every dataset that exists within city government and provides a mechanism for citizens to provide comments on whether the dataset should be released.

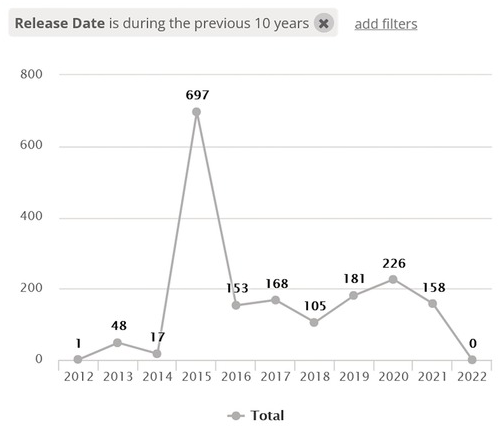

Not all datasets are released. Those that are released comply with standards set out in the Open Data Guidebook, which include anonymizing data, conducting a review, adding descriptive metadata, and ensuring data accuracy. As shown in the figures from the city’s metadata catalog website, many have been released on a range of different subjects (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. City of Philadelphia Metadata Catalog website

EO 12-11 and EO 1-12 stayed as the guiding force of Smart City initiatives in Philadelphia until February 4, 2019, when Mayor Kenney signed EO 2-19, The SmartCityPHL Initiative. That order formally established the SmartCityPHL initiative under the auspices of OIT, subject to the guidance of an advisory committee whose goal is to “guide and support the implementation of the key actions outlined in the SmartCityPHL Roadmap” (Kenney 2019, 2). OIT is responsible for maintaining the city’s open dataFootnote 9 programs and managing the SmartCityPHL initiative.

Pragmatism Reflected in Procurement and Departmental Operations

Apart from the agenda and actions of the Mayor’s Office, various city departments procure and deploy smart tech as needed in their day-to-day operations. The types of technology run the gamut, but generally include basic ICTs. Many departments have their own IT experts and make independent planning, procurement, and deployment decisions. We have not canvassed all departments and their activities,Footnote 10 but many interviewees emphasized how, in the 2010–2015 timeframe, different city departments approached data and technology independently, in a piecemeal, siloed, and trial-and-error manner. The primary considerations were pragmatic, focused on existing needs, available budget, and compliance with general procurement rules.

The procurement process for the City of Philadelphia is outlined in Philadelphia Code § 17-100. These procurement rules concretely define how bidders submit proposals to the City of Philadelphia to obtain contracts for work with the city. As the city has increased procurement of smart technology, it has adapted procurement rules to ensure that technology-based projects meet standards set by the various Executive Orders discussed earlier. For example, the city requires that bidders meet data standards that comply with the city’s Application Programming Interface (API) standards, the ability to integrate data into the city’s data store, and the ability to provide the data to the city in a non proprietary format. The city also maintains licensing terms and metadata requirements for publishing and maintaining data for the city’s use or for release to the public, which complies with the OpenDataPhilly project standards. According to one interviewee, with respect to data, “the default in city contracts is that the city owns it. And a sort of policy default is that whatever we can eventually make public we do” (Hecht 2021a). Generally, if there is concern or uncertainty over whether a certain field in a dataset can be made public, the law department, which has a data privacy review board, is consulted (Carolan 2021). Some datasets have been withheld from the public to prevent reidentification.

One example of departmental independence with respect to smart technology is the police department’s use of facial recognition technology. Since 2012 (Lipp Reference Lipp2015), the department has used JNET facial recognition software, which relies on a database of photos pulled from specific, official sources (such as drivers’ licenses).Footnote 11 Without any public oversight, the police department had run its own trials of the controversial facial recognition software, Clearview AI, which draws photos from a wider range of sources, including surveillance and security videos, social media sites, and the statewide criminal database. In March 2020, the Philadelphia City Council passed a resolution calling for the Philadelphia Police Department as well as state and federal law enforcement officials to “establish clear boundaries and issue transparent policies regarding the use of facial recognition technology to ensure that this technology does not lead to racial biases in policing practices and outcomes or infringe on individuals’ civil liberties” (Jones Jr 2020, 2). While nonbinding, the City Council resolution reflects public concerns about the exacerbation of existing biases in law enforcement practices by using facial recognition software and recent studies showing the disparity in the accuracy of facial recognition technology when used on women and people of color (Buolamwini and Tinnit Reference Buolamwini and Timnit2018: Grother, Ngan, and Hanaoka Reference Grother, Ngan and Hanaoka2019; Grother, Quinn, and Phillips Reference Grother, Quinn and Phillips2011).

Smart City/Tech Planning and Governance Dilemmas

Our study revealed three major dilemmas in Philadelphia’s approach to smart tech planning and governance in the 2010–15 timeframe.

First, community members began to recognize and reject smart city/tech rhetoric plagued by hype, unrealistic expectations and promises, and a failure to be grounded in realities of Philadelphia communities.

Second, and related to the first, there was a disconnect between the smart tech planners and users (mostly government actors but also vendors and consultants, such as IBM in the DOR story) and smart tech beneficiaries, including residents, businesses, and visitors. As one interviewee put it, to cut “through the hype … you need to know the people who are actually going to have to use that technology in city government and the people who are going to be most impacted by that kind of change … engaging them in the conversation, understanding what their current condition is, what they’ve tried in the past, and then also what they would like to address moving forward.”

Third, while the independent, pragmatic approach taken by many city departments was understandable and laudable, it also created redundancies and inefficiencies. Interviewees described departments as “siloed” and emphasized the need for better interdepartmental communication and coordination. One interviewee suggested that an obstacle to better coordination was simply political, as different administrations have different agendas. A similar observation was made regarding political differences across departments. Finally, interviewees suggested that “red tape” and bureaucracy impeded smart tech deployment.

Awareness of these three dilemmas began to surface and manifest demand for a new approach to smart tech planning and governance, which is reflected in the SmartCityPHL Roadmap.

Smart City Planning and Governance: 2016–2021

By 2016, the aspirational smart city promoted by Mayor Nutter, IBM, and many others in 2011 seemed to have faded and been replaced with something quite different. Expectations and imaginations changed with experience. Pragmatism in the day-to-day operations of city government coupled with lessons in what smart tech and data could actually do (and not do) tempered exuberant optimism and hyped rhetoric. The DOR story was just one factor, among many. The shift in outlook and approach emerged gradually, beginning around 2014. While this observation surfaced in various interviews, we highlight the narrative of Ellen Hwang, who led the drafting process for the SmartCityPHL Roadmap and became the first Smart City director with OIT. In speaking with us, Ms. Hwang (2021) recalled her first job for the City of Philadelphia as part of the innovation management team in OIT:

[I was] tasked to think about process, how folks within the city of Philadelphia, [were] thinking about how they approach problem solving and how can they arrive at different solutions that perhaps they would not arrive at. [I was] assigned a lot of work around procurement reform, which [is] really how I ended up entering the Smart City [field]: what are we buying, what are we getting services for, who are the companies that keep wanting to talk to the city of Philadelphia, what are they pitching to us, how do we wrap our heads around all this new technology … and what’s our criteria for evaluating that?

Ms. Hwang (2021) explained a particularly influential experience (which another interviewee also mentioned). OIT had used the city’s “Small Contracts, Big Ideas” website to post Requests for Information (RFIs) as a “a good way for us to communicate things that government wants to learn about from folks who want to engage in procurement with the city.” One RFI concerned leased towers on several building sites that the city could be using more productively. Specifically, “thinking about … smart technology, … we cast a huge wide net, kept it super vague, and that RFI process, produced … over 200 responses.” Ms. Hwang (2021) then emphasized:

that’s when it started, this dialogue around … the process of figuring out how to consume all [the] responses that came in and engage a wide stakeholdership within city government, including the streets department, transportation, infrastructure systems, IT, a chief administrative office, and a few other departments … everyone works together in the city in some ways, and in other ways, totally not, and certainly in reviewing RFI and RFPs, … it’s [typically] a bit more siloed.Footnote 12 …

And so this was a kind of an experiment to see when we adopt technology is there a better process for reviewing? And if there is, what are the criteria that we’re looking for to evaluate these things? And so we had to develop essentially an Excel spreadsheet that kind of mapped out all the responses we got, here’s how they relate to city government, here’s who might be most interested in what solutions, but then how do we have dialogue on it.

Ms. Hwang and her team convened interdepartmental meetings to “review these opportunities and to provide a strategic lens at seeing is there actually something bigger that we weren’t thinking about when we first set out to think about these tower leases?” She explains that mindset: “initially it was, how do we maximize assets that we have, tech assets that we have as a city for other things, and it ended up becoming what it is today … [the SmartCity PHL] initiative and having more cross-departmental dialogue around how do we actually adopt technology, and in a way that actually is meaningful and is actually going to improve city services.” During the conversation, she reiterated and emphasized the word actually, drawing a stark contrast with speculation and hype about smart tech. Yet the message was not pessimistic. Rather, as we discuss below, it resonated with the incremental, pragmatic, problem-solving approach to smart tech seen in the SmartCityPHL Roadmap.

In addition to improving interdepartmental coordination and communication, Ms. Hwang emphasized how the RFI-for-leased-towers experience demonstrated the need for the city to better leverage its resources, including limited budget, by being “more opportunistic about what is actually happening outside of city government.” This included building better relationships with industry and the community. She explained that the marketplace moved ahead of government and at the same time bombarded the government with proposals. “There was a lot of confusion on how to even just manage the sheer [number] of companies that were coming to city government.” To be more opportunistic and deal better with vendors and proposals, the community needed shared “terminology and education” about smart tech, and this required engagement and relationship-building – “everything that feeds into a good governance model.”

“From the beginning in 2016, the city approached the challenge strategically. Rather than tackle individual projects piecemeal, as so many cities have done, Philadelphia’s Office of Innovation and Technology (OIT) decided to create a roadmap that would guide and ensure long-term coordination of its wide-ranging projects” (Knowledge at Wharton 2018). Emily Yates, the current Smart City director for Philadelphia, described the roadmap as “a more organized approach to how we operate as a smart city and how we want to grow as a smart city.”

This shift to a strategic, holistic, city-wide plan required an assessment of what was already being done. OIT identified a variety of different projects, often siloed from each other. Figure 5.2, from the SmartCityPHL Roadmap, resulted from a thorough inventory of the city’s many existing smart tech assets and initiatives.

Figure 5.2. City of Philadelphia SmartCityPHL Roadmap (p. 5), Survey of Existing Assets and Initiatives

Notably, many of these assets/initiatives constitute meso-level action arenas for which further GKC-based case study research would be useful. We discuss DataBridge in the next subsection and in our discussion of the meso-level action arena concerning Vacant Property Management.

To create a roadmap, the city established the SmartCityPHL initiative in early 2017, designated OIT as the lead department, and formed a working group including various city offices and departments. At the outset, the roadmap identifies four guiding principles – being locally inspired, innovative, equitable, and collaborative – and explains the methodology used to develop the roadmap – including an assessment of existing assets and initiatives, focus group interviews, identification of gaps and opportunities, working group brainstorming sessions, benchmarking against peer cities, and engagement with external stakeholders. The principles reflect a different set of community goals and objectives than had animated the smart tech vision in prior years.

The roadmap integrates smart city/tech planning and governance processes. It outlines three macro-level strategies: (1) building the policy foundation and governance infrastructure for meso-level projects and initiatives, (2) establishing consistent processes for engaging community members, and (3) developing sustainable funding mechanisms. We briefly describe the first two strategies, both because they relate most directly to the governance concerns of this case study and because they are developed in more detail in the roadmap; the discussion of funding is quite limited.

Smart City Foundations: Governance Structure, Policies, and Master Strategy

According to the SmartCityPHL Roadmap, “[a] strong governance structure is arguably the most important foundational element to smart city success” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 8). The roadmap establishes the following model: Executive leadership, which sets “vision and direction,” a Smart City director, who “collaborates and partners to inform and implement activities,” an Internal Working Group, which “collaborates and partners to inform and implement activities,” and an External Advisory Committee, which “provides advisory services, research, funding, solutions, and workforce capacity” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 8). In addition, according to Emily Yates (2021), the current Smart City director, “We are working to establish a task force, a third-party validation of sorts, so it will not be comprised of people in the Smart City advisory committee, it will be comprised of academics … to ensure that we are thinking of all community members.”

This structure, shown in Figure 5.3, aims to “drive … collaboration and standardization … [and to] solidify the City’s decision-making process, reporting structures, and roles and responsibilities of participating members.” While, at first glance, this new structure may seem to centralize decision-making and other governance powers within OIT, it does not go that far. Rather, it provides a central “hub” within city government for strategic development, coordination, communications, policy development and evaluation, and expertise regarding data, IT, and other related components of smart tech. Departments continue to have their own IT staff and make their own procurement, deployment, and other decisions regarding data and smart tech. The Smart City director and staff facilitate collaboration and function, at times, as consultants for other departments. During interviews, this role stood out for the city’s many different datasets (and also, to some extent, for network infrastructure, which we do not cover in this study).Footnote 13

Figure 5.3. City of Philadelphia SmartCityPHL Roadmap (p. 8), Governance Structure

Hank Garie (2021), the city’s geographic information officer, explained that various programmatic or departmental datasets had been “messy” both for “historical” reasons and because IT professionals in different departments had been comfortable working in multiple databases without coordinating with one another.Footnote 14 This resulted in a lack of consistency in data standards. Other interviewees discussed the example of the water, streets, and fire departments possessing separate databases: “It makes it really difficult to figure out how to deploy services … you have electricity, and then you have a cable company, and … some … are public companies, and some … are private companies, and they’re all dealing with the same property but nobody can talk about the same property.” (We discuss this example further in the meso-level action arena section.)

Efforts by the OIT CityGeo team to address these types of concerns resulted in the creation of DataBridge, an integrated data warehouse and platform for geospatial and select non-geospatial data. DataBridge enables data sharing and provides city-wide infrastructure for analytics and applications.Footnote 15 OIT maintains the infrastructure, consisting of various pooled resources including technical know-how, software, and deployment managers. In alignment with the city’s general commitments to open data, transparency, and providing useful smart tech applications to the public, DataBridge aims to enable appropriate data flow to the city’s open data applications. Data flow enabled by DataBridge is shown in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4. City of Philadelphia DataBridge

As seen in the figure, DataBridge enables different communities to publish and access data, and it also serves as the backbone for department-specific applications. DataBridge thus serves the administration, city departments, vendors, and partners that use the service to publish data, and it also serves the broader community that uses applications, such as OpenDataPhilly, OpenMaps, and CityAtlas.

Over the past ten years, the geographic information system (GIS) management team mostly focused on sharing data for “mapping, analysis, and city services.” In recent years, this department has focused on developing a secure and reliable foundation to coordinate, organize, and share city data internally and with the public. One interviewee suggested that the recent shift in the dialogue surrounding smart technology and data over the past two years has led departments to be “less skittish” about releasing data; it has become a “habit” for departments to publish their data. The interviewee explained that growth in literacy surrounding data publishing and the existence of mutual trust among stakeholders are catalysts in this culture change.

Coordination among stakeholders is critical to successful data sharing. For example, Kistine Carolan (2021) of OIT created a spreadsheet of all stakeholders to be informed and “kept in the loop” prior to the publication of any datasets. “[W]e’ve got a spreadsheet [of] all the stakeholders. And [it indicates] here’s the place in the process where we need to plug these people in, so that we make sure that when that data set hits the streets nobody’s caught by surprise.” At times, OIT may resolve conflicts among stakeholders. Hank Garie (2021) described a disagreement among the police department, the Mayor’s Office, and the press office about whether to share/publish crime data.

At the end of the day, the data out there is open data, and it’s been well received, and those people who had some concerns were able to back off and say “Okay for the public good, we’ll put out the data.” So it was very much a negotiated solution, but everybody who needed to be at the table had an opportunity to weigh in and express their concerns.

The regularly updated crime incident dataset is hosted on OpenDataPhilly alongside several visualizations for viewing and understanding the dataset. The dataset contains crime data from 2006 through to the present; each reported crime is categorized along with the block number where the incident occurred.

The SmartCityPHL Roadmap also recognizes that privacy and security policies are fundamental. The city has had privacy and security policies in place, as well as data-sharing agreements among departments, and the roadmap states high-level commitments to continue revising and updating those policies in light of changing circumstances and to “better understand the concerns of community members and privacy advocates when initiating smart city projects” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 9).

In addition, the roadmap calls for the development of a “formal master data strategy,” which, among other things, would include creating a formal inventory; establishing governance standards and technology specifications, and requirements for procurement, upgrades, and vendors; and workforce training. The master strategy would be guided by the following questions:

What are we trying to understand?

How will we manage sensor data?

Who owns and manages the data?

How will we secure the data?

How will we analyze and operationalize the data?

Throughout our interviews, we heard that OIT has been and still is working on these policies and the master data strategy. Some interviewees noted that the pandemic had caused a shift in attention and priority and, as a result, progress on these issues had been delayed. (We do not delve further but note that this is another action arena ripe for further GKC-focused study.)

Community Challenges and Engagement

Beyond structure, policies, and strategy, the roadmap grounds the city’s approach to smart technology in pragmatism, which had been present and rising in prominence in prior years (as previously discussed). According to the roadmap, “it is important that any smart city project the City pursues is grounded in a challenge or problem that aligns with its broader mission and purpose.” To ensure such grounding and alignment, the roadmap outlines, as seen in Figure 5.5, a process for selecting and evaluating “appropriate and feasible smart city projects.”

Figure 5.5. City of Philadelphia SmartCityPHL Roadmap (p. 16), decision-making process

The roadmap effectively outlines an applied version of comparative institutional analysis. “The first step is to establish a problem statement that conveys a challenge we are facing or trying to solve” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 17) and then “solution paths need to be identified” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 17). This step entails compiling a comprehensive list of ideas and potential solutions, drawing on internal and external sources. “Once we gather a long list of solutions, we will evaluate and prioritize them through criteria based on [a series of] questions” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 17). This approach highlights issues present in the city, and directly works to target initiatives toward solving the identified issues, seeking to achieve tangible improvements in the actual lives of community members.

Notably, the pragmatic process envisioned in the roadmap is a statement of strategy and does not constitute a binding rule and, to our knowledge, has not yet become a widely followed norm. Throughout the city, departments choosing to pursue smart tech projects need not follow these steps precisely. It remains to be seen whether/how the strategy and process become internalized.

The practical orientation to evaluating projects is further developed in the so-called Pitch + Pilot Program, usefully summarized in Figure 5.6 (from the roadmap).

Figure 5.6 City of Philadelphia SmartCityPHL Roadmap (p. 18), Pitch + Pilot

Pitch and Pilot, according to Emily Yates (2021, 13:40:48), is “[in] its very essence, a mechanism that was developed via the roadmap to create a more transparent way for the city to engage with the private sector to solve municipal challenges through tech and data.” It is a work in progress with a very limited budget, intended to be experimental and incremental. To date, the program has supported a handful of projects, summarized in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2. Pitch and Pilot programs

| Program | Partnership | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Urban Mining Initiative | Metabolic (Netherlands-based company) | Piloting an urban mining tool “to predict the amount of waste from demolished buildings that could be reused in new construction and where construction demand exists to use those materials” (Hecht 2021b). |

| Sustainability and Waste Management Initiative | Retrievr (a New York-based startup company) |

|

| Health Equity and Spatial Justice Initiative: Improving built environments | State of Place |

|

| Street improvements | GoodRoads (North Carolina-based company) |

|

| (Impending project) To provide services that support meal distribution | TBD | City officials have announced a new challenge involving the creation of a platform to provide logistical support for meal distribution. |

Finally, we note that the SmartCityPHL Roadmap places emphasis on engaging the community, through efforts such as forming subcommittees like the Citizens and Communities Subcommittee, which is “comprised of community-facing departments” and will be dedicated to “shaping and leading community engagement strategies and ensuring that solutions and projects will improve the lives of residents” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 8). In the second step of the governance process, identifying solution paths, the city will not only internally generate solutions, it will also “engage with a broader community to identify interesting and potentially impactful smart city solutions” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 16). Also among the factors utilized to evaluate and prioritize potential projects is community impact (City of Philadelphia 2019, 16). The criterion will ask whether “the program tangibly improves the experiences and outcomes of the community” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 16). Aspects of the roadmap such as these highlight the emphasis placed on community needs and involvement. Yet during our interviews, when we asked about how members of the broader community (beyond government) were actually involved in planning and decision-making processes, there was very little to report. Some interviewees acknowledged that there was less community engagement than promised or intended. The pandemic, we were told, made community outreach and engagement much more difficult. But, we were also told, it remains a pillar of the roadmap and the strategic plan, and it would be a priority going forward.Footnote 16

City-Wide Use and Governance of Smart Tech in Managing Vacant Property (Meso-Level Action Arena)

We now turn to vacant property management as the relevant context for a meso-level action arena.Footnote 17 How should Philadelphia address the causes and effects of wide-scale abandonment of thousands of residential and commercial properties within the city? How might data and smart technologies help? What are the opportunities and governance challenges? These difficult questions are hardly unique to Philadelphia. A similar set of concerns is playing out in rustbelt and eastern cities across America, including Detroit, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago, and Buffalo (Sisson Reference Sisson2018). The genesis of the vacant property crisis and how local leaders choose to address the problem may vary across cities. To situate our analysis in a broader background, we present a brief history and explain the general vacant property management problem. Then we describe how Philadelphia has approached the use and governance of supposedly smart technologies, including data, in managing vacant properties throughout the city. While each city is unique, the lessons from this Philadelphia case may be useful for other communities facing significant vacant property challenges.

Background

History and Context

Like many other American cities, Philadelphia experienced significant population growth in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Biggest US Cities n.d.), bringing exponential growth in commercial and residential properties. As noted by Schilling and Hodgson (Reference Schilling and Hodgson2013, 7), “Known as the ‘workshop of the world,’ Philadelphia was home to a growing manufacturing economy that spurred population growth, which in turn sparked private investment in the housing market and municipal services.” In the latter half of the twentieth century, concurrent phenomena brought about the vacant property crisis. First, technological evolution and globalization resulted in deindustrialization of urban neighborhoods nationwide. As a result, inner city factories closed, and many jobs were lost. For example, in Philadelphia, “In 1880, 52% of city jobs were in manufacturing, falling to 30% in 1950, 10% in 2000 and 3.5% today” (Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation 2017, 3).

A second factor driving the increase of vacant properties in American cities was the growth of suburbs. The interstate highway and improved public transit allowed workers whose jobs remained in the city to live in the suburbs and easily commute. Coupled with the “white flight” phenomenon in some cities, suburban growth may have led to abandonment of many inner-city residential units and a significant population loss. From 1960 to 2021 Philadelphia’s total white population fell by more than 62 percent or more than 900,000 residents and white persons changed from approximately 73 percent of the city’s population in 1960 to approximately 35 percent in 2021 (US Census Bureau 1966, 2021).

The migration of white residents from the city to surrounding suburbs drastically impacted northeast Philadelphia as the percentage of white residents fell from 92 percent in 1990 to 58.3 percent in 2010 (Pew Charitable Trusts 2011). Suburban growth, as well as other social and economic changes, led to significant overall population loss in Philadelphia. For example, at the height of its population in 1950, Philadelphia had approximately 2.071 million people (US Census Bureau 1950, 38-15). The population declined more than 23 percent to approximately 1.584 million by 2019 (US Census Bureau 2019). For comparison, the population of select Philadelphia suburban counties grew by 334 percent (Bucks County), 230 percent (Chester County), and 135 percent (Montgomery County) over the same period (US Census Bureau 1950, 38-15; US Census Bureau 2019).

A third factor in vacant land in some cities was the federal redevelopment policies of the 1950s to 1970s, especially the Urban Renewal Program. This program was enacted in 1949 to remove “blight” in American cities. Nationwide, “renewal funded proposals to raze and redevelop 363,637 acres of land – that’s roughly 568 square miles” and more than 300,000 people were relocated (University of Richmond 2021). As noted by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy:

Vacant land in urban areas is not always the unintended result of financial drivers or city policies. The urban renewal policies of the 1950s, 60s and 70s aimed to improve the quality of the city environment. By condemning entire low-income, poorly maintained neighborhoods, and relocating the residents away from the urban core, often in isolated, poorly designed public housing, centrally located land was made available for redevelopment as high-end residential, commercial and retail property. This process of gentrification as a means of urban renewal was not always successful; some cities accomplished the razing of old structures but not the redevelopment, leaving large tracts of vacant land and displacing local residents to less desirable locations.

By the end of 1965, Philadelphia had reserved $209 million in federal funding for urban renewal, second only to New York (Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia n.d.). Under the “Philadelphia Approach,” renewal emphasized “small scale, minimal displacement, citizen engagement, the preservation of neighborhood institutions, focus on urban design, and historic preservation” (Ryberg Reference Ryberg2013, 194). Despite these efforts, the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab estimates that urban renewal in Philadelphia displaced more than 13,000 families (University of Richmond 2021). Philadelphia conducted more than sixty Urban Renewal Projects, in areas such as Society Hill, Independence Mall, Nicetown, University City, Eastwick, and near Temple University (University of Richmond 2021).

Despite some efforts to do things differently in Philadelphia, approximately 40,000 vacant properties remain scattered throughout Philadelphia (City of Philadelphia Reference Kenney2020). Of these, 74 percent or approximately 30,000 properties are privately owned (City of Philadelphia Reference Kenney2020), with the balance taken into public ownership by the city through tax foreclosure, surplus city properties, and other mechanisms. In addition, 1.7 percent of properties in the city are “zombies” – properties where an owner abandons the home, but the lender has not undertaken foreclosure (Dickerson Reference Dickerson2020). Regardless of occupancy status, private owners are required by city ordinance to maintain the property, including litter removal and securing the property (City of Philadelphia Reference Kenney2020, § PM-4). Vacant property in Philadelphia is not evenly spread across all city neighborhoods. Pearsall, Lucas, and Lenhardt (Reference Pearsall, Lucas and Lenhardt2013, 167) explain that:

The older industrial neighborhoods of north and south Philadelphia, as well as the once prosperous middle class streetcar suburbs of west Philadelphia, have disproportionately large quantities of both vacant lots and abandoned structures. Of all Philadelphia’s neighborhoods, Strawberry Mansion in North Philadelphia and Manuta in the west of the city are two of the most blighted in the city, characterized by large numbers of abandoned properties and vacant lots that have been left undeveloped and unimproved for many years.

Historically, seven Philadelphia city or quasi-public agencies have played a significant role in managing or selling the publicly owned or managed vacant properties. These include:

The Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation (PHDC), a quasi-public entity funded by the city which manages the city’s land bank. The land bank was created by the City Council in 2013 under bill number 130156-A02 (City of Philadelphia 2013). The land bank conducts four key tasks: “Consolidate surplus City property … Acquire tax delinquent property at Sheriff’s sale … Dispose of surplus publicly-owned property ... Provide temporary access to property held by the Land Bank” (Philadelphia Land Bank 2019). The lots may be sold to individuals, developers, or nonprofit organizations (Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation 2022). Properties are sold at market rate, although discounts are available for properties that will be sold to nonprofits for public use or to neighbors for side yards (Philadelphia Land Bank 2020). These properties were acquired either from tax-delinquent sheriff’s sales or consolidated from existing properties already held by city agencies.

Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, now a part of PHDC.

The city’s Department of Public Property, which manages and maintains properties where city staff work (City of Philadelphia Department of Public Property 2021). PHDC now serves as the operational arm for DPP vacant property sales.

The city’s Vacant Property Review Committee (VPRC), a board comprised of fourteen people with a chairperson appointed by the city council president. In recent years, VPRC was accused of mismanagement of assets under its control, including “political meddling” in disposition of properties (Briggs Reference Briggs2019). In 2019, there was City Council legislation to fold the work of VPRC into the land bank (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2019).

The Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC), which sells and leases industrial and commercial properties (City of Philadelphia 2 Reference Hecht2021).

The Philadelphia County Sheriff, which hosts public auctions of properties taken due to foreclosure or tax delinquency (City of Philadelphia, Office of the Sheriff 2021).

Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA), which owns and manages affordable housing; with federal approval, it can sell homes and lots it owns (Philadelphia Housing Authority 2009).

The Department of Records,Footnote 18 the Department of Licenses and Inspections,Footnote 19 the Department of Planning and Development,Footnote 20 the Department of Revenue,Footnote 21 and the Office of Property AssessmentFootnote 22 also have roles in addressing the issues created by vacant properties. Furthermore, the Philadelphia Fire Department, the Police Department, the Water Department, and the local electric utility PECO each need information about vacant properties to provide public services and undertake their respective responsibilities.

Social Problems Caused by Vacant Properties

There are three types of social harms that arise from the vacant property crisis in Philadelphia (and elsewhere). First, there are effects on neighborhoods and residents, including:

Crime: There is a relationship between crime hotspots in the city and areas with a significant level of vacant property (Philadelphia Land Bank Reference Lipp2015, 20). As described by Goldstein, Jensen, and Reiskin (2001, 2), vacant properties “provide convenient venues for criminal activity, such as drug trafficking and gangs.” Productively reusing these vacant properties can help to reduce neighborhood crime. For example, scholars at the University of Pennsylvania studied the effects of restoring blighted and vacant lots and among other results they found reductions in crime, gun violence and burglary (Branas et al. 2018, 2946).

Safety: Community members – especially children and homeless persons – are often attracted to vacant properties, many of which have unsafe structures or other hazards. “Abandoned buildings attract the attention of neighborhood children, who may decide to use them as play areas, even though they are poorly maintained and may be unsafe” (Goldstein, Jensen, and Reiskin 2001, 2). In addition, “The poor condition of most abandoned buildings makes them fire hazards. In older neighborhoods with minimal space between buildings, fires can easily spread from one building to another. A fire in an abandoned building may very likely result in the destruction of occupied buildings, displacing residents and increasing neighborhood blight” (Goldstein, Jensen, and Reiskin 2001, 3).

Trash: Vacant properties often become dump sites for trash and other debris (Loesch 2018). These trash-strewn sites not only attract vermin and are unappealing for neighborhood residents, but they are also costly for the city to maintain. “During my time at the City, we estimated that the city was spending almost $10 million a year cleaning up illegal dumping, oftentimes on vacant lots” (Esposito Reference Esposito2020).

Second, and related to the neighborhood issues, are impacts on the delivery of city services, including trash removal, policing, firefighting, and addressing water leaks on-site. Public service providers generally face an added degree of uncertainty in characterizing risks and providing services when the conditions of the property are unknown, causing administrative complexities and adding cost. “In weak markets characterized by rising levels of vacancy and foreclosures, tax revenue and property values fall and the cost of providing essential services like policing, fire protection, and code enforcement rise” (Philadelphia Land Bank 2015, 20).

Finally, vacant properties have significant economic impacts. Not surprisingly, vacant properties have a negative effect on the value of surrounding homes as well as perceptions of the neighborhood. “The average household loses over $8,000 in property value due to vacant property in Philadelphia” (Philadelphia Land Bank 2015, 18). As noted by Susan M. Wachter and Kevin C. Gillen (Reference Wachter and Gillen2006, 4) of the University of Pennsylvania, “Our findings indicate that adjacency to a neglected vacant lot subtracts 20% of value from a home relative to comparable homes farther away from the site.” In addition, abandoned or vacant property may also result in lost tax revenue for the city, which may impact the delivery of public services. According to a 2010 report by Econsult and the University of Pennsylvania for Philadelphia’s Redevelopment Authority, vacant property cost the city:

1. “$3.6 billion in lost household wealth. Vacant parcels have a blighting effect on nearby properties, reducing values by 6.5 percent citywide …

2. Over $20 million in city maintenance costs each year. Though the City controls only a fraction of the vacant parcels within the city, it has to bear significant costs to maintain all of them – waste clean‐up, pest control, police and fire – totaling over $20 million per year.

3. At least $2 million in uncollected property taxes each year. 17,000 vacant parcels are tax delinquent, most by over a decade, owing a total of $70 million to the City and School District in back property taxes.” (Econsult Solutions 2010, v)

Where Vacant Property Management Meets Smart Technology: Meso-Level Action Arena

Vacant property management has always faced data and knowledge problems. Simply keeping track of the quantity and qualities of vacant properties can be daunting. However, such knowledge is essential to effective management (including sales) of properties and provision of public services. There also are significant challenges rooted in the distribution of knowledge and responsibilities concerning vacant properties. Over the past decade, Philadelphia has tried to tackle some of these obstacles by improving its organizational processes and procuring, developing, using, and sharing with the public data and smart tech. In this section, we describe those efforts and the roles that smart tech plays in vacant property management.

Stakeholders

Numerous stakeholders face knowledge problems. We identify three main categories. Local community organizations and residents have a vested interest in the acquisition and productive reuse of vacant properties in their neighborhoods. These organizations may be concerned about which vacant properties are available for purchase and about how, when, to whom, and for what purpose the properties will be sold. Smart technologies that manage, track, estimate value, and communicate knowledge about the sales process can benefit these community organizations and residents.

These tools would also be useful to private developers and lenders, who need this data to make informed investment decisions. The goals of these private entities might conflict with the neighborhood groups, but the same technology could aid both.

Numerous city departments need information about where vacant properties are located and the condition/status of those sites. Understanding the number, locations, and types of vacant properties is central to PHDC’s redevelopment mission. During our interview, Professor Allison Lassiter provided a few additional examples of the city’s knowledge-sharing needs. Before running into the building, for example, firefighters need to know whether it is believed to be occupied and what types of hazards may be present. When leaks occur, the city’s water department must understand whether the line serves a vacant structure. Smart technologies such as jointly accessible tracking databases, public reporting systems, and sensors could serve as tools to aid in the provision of these and other city services. The following sections describe how Philadelphia has deployed smart technology in aid of key stakeholders.

Knowledge Problems and Smart Tech Solutions

Given the significant impact of vacant properties and the needs of varied stakeholders, there are several knowledge questions that cities must answer. The following are representative:

Location: Where are vacant properties located?

◦ Are the properties clustered in specific neighborhoods?

◦ What has been the impact of these vacant sites on the surrounding community?

Ownership: Who has title to the vacant properties?

◦ Are these owners in arrears on property taxes?

◦ Which properties are owned by the city and which by private entities?

◦ When and where should the city begin the tax foreclosure process?

◦ Where and when should the city condemn and take the vacant property for repeated code violations?

Status of the vacant site: Are vacant property owners maintaining the site, as required by Philadelphia law?

◦ Are there crimes or safety hazards at the site?

◦ What is the status of utilities, including water and electrical, at the property?

Disposition: Which properties are for sale by the city?

◦ What is the city’s plan for property reuse (commercial, multi-family residential, homeownership, side yard, community park, urban agriculture, etc.)?

◦ Who and what are involved in the property disposition process?

◦ How will upcoming property sales be communicated to the public, nonprofit community organizations, and developers?

There are many opportunities to use data, information and communications technologies, and smart technology to address these and related questions. In accordance with the macro-level strategy (discussed previously), the city has focused mostly on using the internet to provide usable open data as shared infrastructure for all stakeholders as well as mapping and visualization tools that leverage open datasets.

Smart tech deployment and governance in this action arena follows a familiar logic. The city has made a significant effort over the last several years to adopt technology policies that allow for more transparent government and enable open pipelines of data for everyone to use. Broadly speaking, the city sends data collected through various programs to DataBridge. Aggregated data is then published to a data repository, like the Philadelphia metadata catalog or a website like OpenDataPhilly. Once the data is published, it is available publicly for access and manipulation by anyone with an interest. The City of Philadelphia maintains a tool called Atlas for people to explore some of the published datasets.

The Vacant Properties Indicators Model (VPIM) dataset, owned and maintained by OIT, is an illustrative example of how data is published and utilized in the city. The dataset is hosted on OpenDataPhilly. Anyone can download it. The dataset is updated regularly by the city to ensure that the data present is the newest and most useful available. The city maintains two visualization applications that utilize the VPIM dataset: the Vacancy Viewer application and the Atlas application. Both are accessible either by direct link or through the OpenDataPhilly page for the VPIM dataset. On one hand, the Vacancy Viewer application is specifically tailored to the VPIM dataset. It serves to provide an easily navigable map-based visualization system for identifying and ranking vacant property according to the model created in the dataset. The Atlas application, on the other hand, serves a more general purpose. It helps visualize over fifty datasets. The Atlas application allows users to access information about properties across the city and allows users to learn about: property assessments, deeds, licenses and inspections, zoning, voting, and nearby 311 calls, crime incidents, zoning appeals, and vacant property. Atlas is an attempt by the city to unify visualization of geographically relevant datasets. The Atlas application contains a generalized visualization of the VPIM dataset to provide an entry point into viewing Philadelphia-centric data.

One of the stated goals for the DataBridge tool was to provide a streamlined methodology and process for publishing and viewing data. The Atlas application is an example of that streamlined process. However, as the Vacancy Viewer application shows, more specialized tools and visualizations can be created. One clear benefit of open data is innovation and creativity in the manipulation and viewing of the dataset. The City of Philadelphia has done a lot of work to create a platform and tools that can be used to observe and interact with the data they have published.

There are, in fact, many smart technology tools used to assess and manage vacant properties in Philadelphia. A sample of these tools are described in Table 5.3, sorted by the knowledge question each technology primarily addresses:

Table 5.3. Smart tools for vacant property management

| Name | Agency | Address | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacant property location & ownership | |||

| Vacant Properties Indicators Model (VPIM) | Office of Innovation and Technology | www.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=64ac160773d04952bc17ad895cc00680 | Mapping system used by agencies and public to locate vacant properties. VPIM aggregates Philadelphia’s various geographic and administrative data sources to identify indicators of potential vacant property or building. Allows for all departments to be more proactive in assessing, billing, and inspecting vacant properties. |

| Atlas | Office of Innovation and Technology | http://atlas.phila.gov | Master aggregator of city mapping sites. Compiles information about all city properties into one location, including ownership, history of inspections, permits, and licenses, zoning, property value, and 311 service requests. Users can see street and aerial view. |

| Property Map | Office of Property Assessment | https://property.phila.gov | Info on property ownership, sales history, value, permits, licenses, violations, and appeals. The site also includes physical characteristics such as lot size, year built, building condition, zoning, political district, school catchment, and police district. Properties can be assessed within a 250-foot radius. |

| Status of the vacant site | |||

| 311 System | City of Philadelphia | www.phila.gov/departments/philly311/ | Residents use system to report vacant lot issues and request city clean-up. City refers request to owner to clean up lot. If does not occur, city will address issues and bill owner (City of Philadelphia 2020). |

| Litter Index | Office of Innovation and Technology | www.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=4856a523514c4c02ba0e28e6a0e8c42c | “A map-based survey conducted by city staff of the litter conditions on city streets, vacant lots, parks and recreation sites, riverways, transit stations, and other public spaces. Surveyors identify the types of litter they see and give a 1–-4 litter score, with 1 being the cleanest and 4 being the most littered. The city then creates an indexed map of litter conditions across Philadelphia using the data collected through the surveys” (City of Philadelphia Litter Index 2019). |

| Disposition | |||

| Property Search Map | PHDC | https://phdcphila.org/land/buy-land/property-search-map/ | Map indicates available properties for sale from land bank. Allows developers and purchasers to consider how to assemble multiple sites for development. |

| PHDC Land Management | PHDC | https://phl.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=2eb44decb9464cb79f2132d1c5883674 | Map indicates number and type of available properties. Provides information on zoning, market value, and ownership status. |

| PHDC website | PHDC | https://phdcphila.org/land/buy-land/ | Website summarizes potential uses of vacant property including side or rear yards, affordable housing, community gardens and other public uses, and commercial activities. Includes information on requirements and application/RFP process, as well as PHDC strategic plan and policies. |

| PIDC Available Properties | PIDC | www.pidcphila.com/real-estate/available-properties | Provides information about available commercial and industrial properties for both city and privately owned properties. Includes size, zoning, and types of available public incentives/subsidies. |

| Sheriff’s Office Property Search | Sheriff’s Office | https://phillysheriff.com/property-listing/ | Website indicates location, status, and description of properties to be sold at Sheriff’s auction |

SmartCity PHL Roadmap and Knowledge-Smart Tech Gaps

The SmartCity PHL Roadmap includes vacant property management as an area of interest. In fact, the Departments of Licenses and Inspections, Planning and Development, the Waste and Litter Cabinet, the Philadelphia Water Department, the Philadelphia Fire Department, PECO, and the Department of Public Property – all of which have a role in addressing Philadelphia’s vacant properties – are members of the working group supporting development and implementation of the SmartCity plan (City of Philadelphia 2019, 2). Interestingly, none of the other key public agency vacant property owners, including the Philadelphia Housing Authority, the Sheriff’s Office, or the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation, are listed in the SmartPHL Roadmap as members of this group (City of Philadelphia 2019, 2).

The roadmap identifies existing smart technologies, including several that are related to vacant properties. These include the city’s Vacant Property Model, DataBridge, Atlas/MapBoard, and its Litter Index (City of Philadelphia Litter Index 2019, 5). According to the roadmap, the Vacant Properties Indicators Model “identifies potentially vacant properties across Philadelphia by combining city datasets, analyzing and scoring them for every property record in the city. This solution has increased data accuracy and operational efficiency across stakeholders that deal with vacancy challenges” (City of Philadelphia 2019, 11).

As the SmartCity PHL Roadmap has been implemented, however, using smart tech to address the vacant property crisis has not been as successful as one might have expected. Managing/selling vacant properties has not been a major area of focus for OIT or the SmartCity working group. For example, the city’s SmartCity coordinator Emily Yates indicated that while there had been a discussion about including vacant properties among the early Pitch and Pilot initiatives, it did not proceed (Yates 2021).

Philadelphia has made progress in making data publicly available and providing various mapping and visualization tools (see previous section). These steps are important and help address some of the knowledge problems that may stifle stakeholder participation and progress in managing vacant property in the city. Yet, as became clear in our interviews, there is only so much that data and these types of smart tech tools can do. On one hand, many knowledge problems remain. The datasets are incomplete. Some datasets are managed separately and not always easily integrated. Conditions change, sometimes much faster than datasets can be updated. On the other hand, and perhaps much more important, some knowledge problems may not be amenable to data-driven, smart tech solutions – at least, the types being deployed. For example, questions concerning city planning and strategic disposition of vacant properties are not answered by data or mapping tools.