Chapter 2 The short past: or, the retreat of the longue durée

A history undergraduate places aside her work on an assignment for a few hours to surf the Web, and what she sees there worries her. It always troubles her, because her conscience keeps asking her how to connect her work with the world outside the university. She thinks of herself as a reformer, and corruption, pollution, and inequality rock her sense of justice. What can she do to learn about the levers of change, to talk to the public about how they work, to develop a cadre of students trained to think about such things? The answers that her teachers give can be summed up in one disappointing word: focus. Focus her questions; focus on her archival sources. University training, she will hear in many of her courses, is about developing professional expertise in analysing evidence, not answering the big questions. While sophistication with data about the past is well and good for learning to ask precise, academic questions and how to answer them, sometimes our student wonders when and how the big questions can be asked, and by whom.

Students at Oxford in the late 1960s were having a very different experience of historical questions and their relevance. They read news reports of union strikes in Paris where students showed up in solidarity. They read about sexual revolution and the largest migration in American history, converging on encampments in San Francisco where experiments in property ownership, psychedelic drugs, and communal living were under way. All the while, longue-durée historians like Eric Hobsbawm were publishing histories of resistance that contextualised May 1968 in the centuries that preceded it. This episode was not without context, they argued. Rather, centuries of struggle by slaves, working people, and women had preceded and conditioned many of the political movements now voicing their demands in public.1 So while many of the college students reading about Paris or the Prague Spring went to join them, some radicals chose another path, and went in search of history.

The future historian of Germany, Geoff Eley, was one of these students, ‘a young person seeking change in the world’, as he tells us in the first line of his memoir.2 Like many history undergraduates at the time, the best way to understand the warrant and potential of these incipient movements was to understand them against the background of long-term political change. There were few questions in his mind as to whether the public needed thinkers about long-term change: change was everywhere around them. For students reading Tawney and Hobsbawm by day and watching revolution on the television in the evening, history’s imminence was incontrovertible. For this generation, thinking about the future almost automatically evoked the resource of looking at the past. However one chose to think about that history, there was no question about narrowing one’s mind or one’s ambition.

The way that Eley chose to answer big questions when he trained as a professional historian at the University of Sussex in the early 1970s was to focus his vision and narrow his sources. His doctoral thesis treated sixteen years of German naval history and his first articles covered ten or twenty years at a time, as he delved into the archives about the small elite of Germans affiliated with the military who helped to propel their nation to nationalism in the decades leading up to the Third Reich. He pillaged the Freiburg community archive and its military archive for their correspondence, for how they spoke about their political organising, the nation, the people, and foreign policy.3 Eley and most of his generation mastered one archive at a time and worked with the conviction that these intense excursions into the history of the ‘Short Past’ could illuminate the politics of the immediate present.

In the decades since 1968, focusing on narrow time-scales like this has come to dominate most university training in history. It determines how we write our studies, where we look for sources, and which debates we engage. It also determines where we break off the conversation. Yet no revolution comes without a price. The transition to the Short Past meant that fewer and fewer students trained on the long-term perspective that characterised Eric Hobsbawm, for example, who stood out for his willingness to span centuries as well as continents. Whether undergraduates, graduate students, or faculty, most people who work with data about time have been trained to examine the past on the scale of an individual life, not the trans-generational perspective on the rise and fall of institutions that characterised the longue durée. As students in classrooms were told to narrow and to focus, the professionals who deal with past and future began to restrict not only their sources and their data, but sometimes also their ideas.

The examples in this chapter have mostly been drawn from the English-speaking world but we believe that the argument here, as throughout this book, has relevance for historians more generally at a time when short-term horizons constrict the views of most of our institutions. In some fields, broad historical time-scales never went away: for example, in historical sociology or in world-systems theory.4 However, in the field of history, the longue durée – associated, as we have seen, with Fernand Braudel and the French Annales school of historians, but soon more widely diffused – flourished and then withered away. What replaced it – the view of the Short Past – often had its own radical mission, one of changing the world, but it also had its own limitations.

The historians who came of age around 1968 had a very different approach to the past than did those of the longue durée a generation before. As students and writers about history, as thinkers and public intellectuals, this generation found more material in short-term history than, perhaps, any generation before it. Obscure archives of workers’ trade unions in the south of France or the north of England allowed them to look at the micro-dynamics between rank-and-file workers and leaders, to ask questions about how and when group decision-making is possible, and when and how a small group of organised individuals can overturn an entire outmoded system of privilege and production. In narrowing, they found the freedom to take on big ideas and to publish authoritative and insightful perspectives that helped the public to contextualise enormous forces like racism or nationalism as constructed developments rather than as a natural social order somehow predestined to shape human minds for eternity.

The micro-historical perspective of the Short Past helped a historian like Geoff Eley to reflect on politics more broadly, which he did for the profession in The Peculiarities of German History (1984), a precocious and path-breaking co-authored attack on the enduring myth of Germany’s inevitable Sonderweg.5 Sometimes his history was written for the public, published in organs like the London Review of Books, where he helped to keep a discussion of the Holocaust alive and pertinent to the racism that rocked Thatcherite Britain in the years of the Brixton Riots.6 Eley and his cohort were part of a university that believed in using the disciplines, including the humanities, as a tool for rethinking civil society and international order on enormous time-scales. While Eley did his graduate training at the University of Sussex, whose red-brick modernism still bespoke of futurism, colleagues there in anthropology, sociology, and economics were working to advise the United Nations and World Bank about the future of housing and democracy. They were using recent work in the history of technology to reconceptualise programmes of international aid and economic development. They believed in overturning the old order of nations, rethinking the future of India and Africa in the wake of empire, and using technology and democracy to lift up all.7 On campuses such as these, it was still clear that looking to the past was a source of ample material for thinking about futures on a global scale.

It is to this generation, with their ambitions for changing the world, that we owe the strength of the commandment to focus on the past in order to gain insight into the present. In the era when Geoff Eley was learning his trade, the Short Past was committed to public discourse and changing the world, deeply intertwined with riot, revolution, and reform. These ties between historians and social movements were well established in the generation of Sidney and Beatrice Webb and R. H. Tawney, down to the 1960s and 1970s, when American diplomatic historian William Appleman Williams worked with the NAACP in a small town on the Texas coast, and historian of the working class E. P. Thompson delivered sermons to peace rallies in London before going on to help found a major European movement for nuclear disarmament.8 In the 1970s, Hobsbawm’s own attention turned from revolution to the history of invented traditions, allowing him to contextualise the celebration of the ancient battle site of Masada in the new state of Israel alongside other invented traditions, from Nazi Germany to the nation of Ghana to the Mexican Revolution.9 Even as the class of 1968 came of age, the senior historians around them were continuing to respond, often intimately, to political events and social conditions of the present, using the past to make sense of the present. Using the past to look backwards in time and developing firm opinions about the future as a result was nothing new. But in the 1970s, political movements could take on an Oedipal cast.

Young people coming of age in the 1970s entered a political ecosystem that increasingly was bent upon rejecting the institutional ties typical of an earlier generation. In the United States of the Vietnam War, ties with the institutions of rule were proof of the corruption of the older generation, according to anarchist Paul Goodman, one of the inspirations of many a student movement. According to Goodman, ‘the professors’ had given up their ‘citizenly independence and freedom of criticism in order to be servants of the public and friends of the cops’.10 True rebellion had to reject its ties to policy.

Young historians saw themselves as rebels. According to Eley, the cultural turn was a kind of personal liberation for younger historians who ‘bridl[ed] against the dry and disembodied work of so much conventional historiography’, for whom theory ‘resuscitated the archive’s epistemological life’. The rebellion of young historians against old here parallels, in terms of rhetoric, the anti-war, free-speech, and anti-racism youth movements of the same moment in the late 1960s and 1970s: it reflected a call of conscience, a determination to make the institution of history align with a more critical politics. Talking about the ‘big implications’ of this reaction, Eley is direct: historians of his generation took their politics in the form of a break with the corrupted organs of international rule, those very ones that had been the major consumers of longue-durée history for generations before.11

In 1970, the Short Past had another, practical advantage over longue-durée thought: it helped individuals to face the professional and economic realities of the academic job market with something new up their sleeves. A generation with limited prospects on the job market increasingly defined itself by its mastery of discrete archives. As young historians simultaneously infused their archival visits with the politics of protest and identity that formed so vast a part of its milieu, anglophone historians widely adopted the genre of the Short Past; the result was the production of historical monographs of exceptional sophistication.

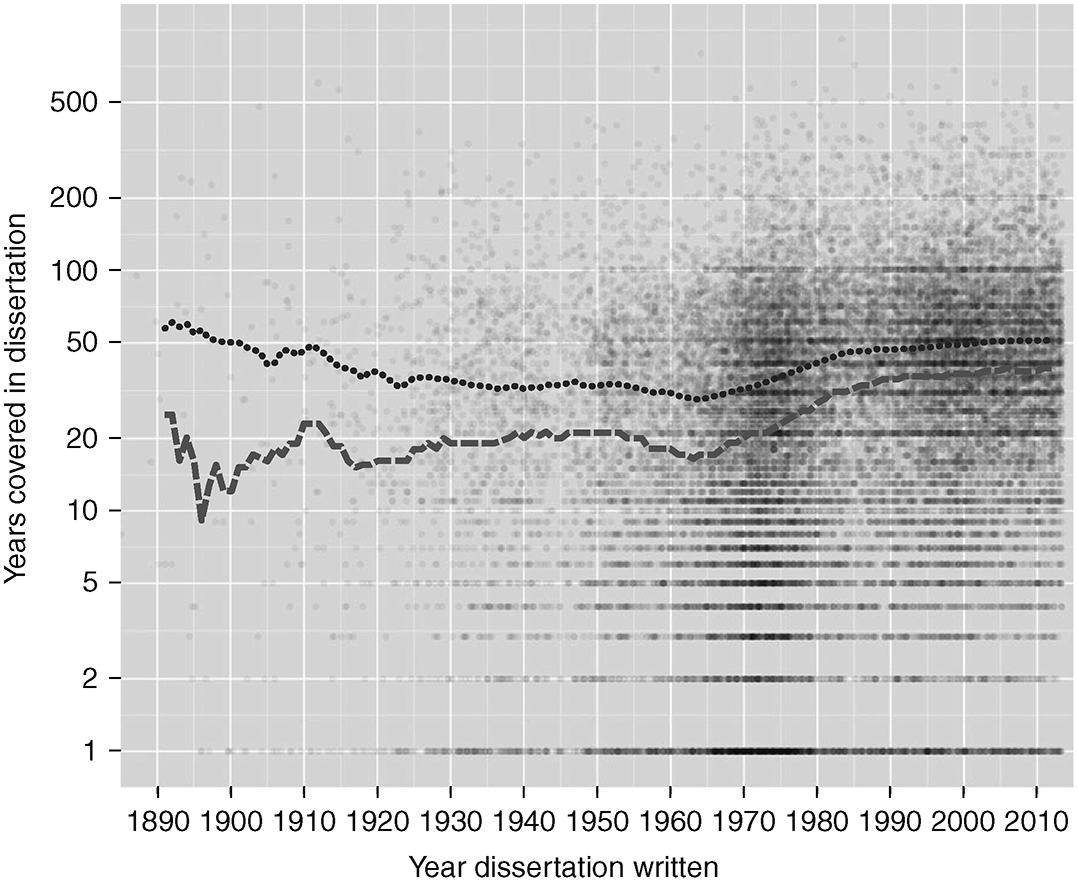

In the United States, state subsidies for the education of returning soldiers under the GI Bill of 1944 had led to an explosion of postwar graduate programmes in all fields, including History. The training time for the PhD was expanded from three to six years, and often extended even beyond that. By the late 1970s, when a new generation of American graduate students came of age in a professionalised university setting, ‘the academic labor market in most fields became saturated, and there was concern about overproduction of Ph.D.s’, reported the National Science Foundation: ‘The annual number of doctorates awarded rose from 8,611 in 1957 to 33,755 in 1973, an increase of nearly 9 percent per year’.12 Insufficient numbers of jobs were created to harbour all of those PhDs, however, and graduates of history programmes increasingly looked to distinguish themselves from their peers through innovative approaches to archives. In the earliest years of doctoral training in the American historical profession, a thesis could cover two centuries or more, as had Frederick Jackson Turner’s study of trading-posts across North American history or W. E. B. Du Bois’ work on the suppression of the African slave-trade, 1638–1870.13 A 2013 survey of some 8,000 history dissertations written in the United States since the 1880s showed that the average period covered in 1900 was about seventy-five years; by 1975, that had fallen to about thirty years. Only in the twenty-first century did it rebound to between seventy-five and a hundred years (see Figure 2).14

Figure 2 Number of years covered in History dissertations in the United States, c. 1885–2012. Note: Median time covered = dashed line, mean length of time covered = dotted line; dots represent the use of a year in a dissertation title.

There were parallels on the other side of the Atlantic. Eley’s memoir of his years on the tightening job market recalls how he found himself fighting alongside his peers for their professional positions. The major weapon used in this battle was an attention to local detail, a practice derived from the urban history tradition, where German and British city histories frequently narrated labour altercation as part of the story of urban community. Indeed, the increasing emphasis on the extremely local experiences in the work of historians such as Gareth Stedman Jones and David Roediger allowed exactly such an examination of race, class, and power in the community that allowed the historian to reckon as contingent the failures of working-class movements to transform the nation.15 Exploiting archives became a coming-of-age ritual for a historian, one of the primary signs by which one identified disciplined commitment to methodology, theoretical sophistication, a saturation in historiographical context, and a familiarity with documents. Gaining access to a hitherto unexploited repository signalled that one knew the literature well enough to identify the gaps within it, and that one had at hand all of the tools of historical analysis to make sense of any historiographical record, no matter how obscure or how complex the identity of its authors. Every historian was encouraged to get a taste for the archives: not to get one’s hands dirty was hardly to be a historian at all.16

As historians of the Short Past began to rethink their relationship to archives and audiences, archival mastery became the index of specialisation and temporal focus became ever more necessary. With a few exceptions, the classic works of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s concentrated on a particular episode: the identification of a particular disorder within psychology, or the analysis of a particular riot in the labour movement, for instance.17 Almost every social historian experimented in some sense with short-durée historical writing to engage with specific forms of institution-making, each filling in a single episode in the long story of labour, medicine, gender, or domesticity. The cases of psychological diagnoses followed a particular model, each study’s periodisation constrained to coincide with the life of the doctors involved with original work – the diagnosis of hysteria, the fad of mesmerism, or the birth of agoraphobia, or Ian Hacking’s discourse in Mad Travelers (1998) on fugue states which departed from a twenty-year medical tradition suddenly deprived of its ‘ecological niche’.18

Biological time-scales of between five and fifty years became the model for field-breaking work in history. The micro-historians revolutionised historical writing about unions and racism, the nature of whiteness, and the production of history itself. Indeed, a flood of doctoral dissertations since that time has concentrated on the local and the specific as an arena in which the historian can exercise her skills of biography, archival reading, and periodisation within the petri-dish of a handful of years. In the age of the Short Past, doctoral supervisors often urged young historians to narrow, not to broaden, their focus on place and time, trusting that serious work on gender, race, and class comes most faithfully out of the smallest, not the largest, picture. Yet, according to Eley, the project of politically engaged social history was largely a failure, due precisely to this over-concentration on the local: ‘With time, the closeness and reciprocity … between the macrohistorical interest in capturing the direction of change within a whole society and the microhistories of particular places – pulled apart’. Eley even contrasted local social history with another politically oriented history, that from the Annales tradition, which much like his own project promised a ‘total’ critique of history of the present.19

The Short Past produced the fundamentalist school of narrowing time horizons called ‘micro-history’. Micro-history largely abandoned grand narrative or moral instruction in favour of focus on a particular event: for example, the shame-inducing charivaris of early modern France analysed by Natalie Zemon Davis or the mystifying cat massacres of eighteenth-century Paris unpacked by Robert Darnton.20 Micro-history had originated in Italy as a method for testing longue-durée questions, in reaction to the totalising theories of Marxism and the Annales School. Its quarry was what Edoardo Grendi famously called the ‘exceptionally “normal”’ (eccezionalmente normale) and its aim was to articulate different scales of analysis simultaneously.21 Its method was therefore not incompatible with temporal depth, as in a work such as Carlo Ginzburg’s study of the benandanti and the witches’ sabbath, which moved between historical scales of days and of millennia.22 Nor was micro-history originally disengaged from larger political and social questions beyond the academy: its Italian roots included a belief in the transformative capacity of individual action ‘beyond, but not outside, the constraints of prescriptive and oppressive normative systems’.23 However, when transposed to the anglophone historical profession, the Short Past produced a habit of writing that depended upon shorter and shorter time-scales and more and more intensive use of archives. In some sense, the more obscure or difficult to understand a particular set of documents, the better: the more that a strange archive tested the writer’s sophistication within a wealth of competing theories of identity, sexuality, professionalism, and agency, the more the use of the archive proved the scholar’s fluency with sources and commitment to immersion in the field. A suspicion towards grand narratives also fuelled a movement towards empathetic stories of past individuals with whom even non-professional readers could identify; such ‘sentimentalist’ accounts risked the charge of ‘embracing the local and personal at the expense of engagement with larger public and political issues’ even as they often earned their authors fame and popularity within and beyond the academy.24

Later generations would take the time horizons of the Short Past as a matter of course. To get a job as a historian, one needed to engage in an innovative reading of the past, and the Short Past lent weight to numerous new interpretations and internecine arguments. The generation of 1968 landed in the middle of an already ongoing social turn, a revolution in looking at history ‘from the bottom up’ and away from the history of elites to the experiences of ordinary people, the subaltern, the marginalised, and the oppressed. Then there was the linguistic turn – a movement adopted from analytic philosophy which historians adapted to their own purposes to reveal the construction of the world and social experience through language and concepts.25 The linguistic turn led to a cultural turn and to a broader revival of cultural history.26 Since then, there has been a series of turns away from national history, among them variously the transnational turn, the imperial turn, and the global turn.27 The authors of this book have both been guilty of promoting the language of turns: one of us recently offered a genealogy of the ‘spatial turn’ across the disciplines generally; the other has surveyed the prospects for an ‘international turn’ in intellectual history more specifically.28 To speak of scholarly movements as ‘turns’ implies that historians always travel along a one-lane highway to the future, even if that road is circuitous with many twists and bends to it. For that very reason, some questioning of turns is in order, along with a readiness to consider the value of returns, such as the return of the longue durée.

So frequent and so unsettling is all the talk about turns that in 2012 the American Historical Review – the anglophone historical profession’s leading journal – convened a major forum on ‘Historiographic “Turns” in Critical Perspective’ to survey the phenomenon.29 So-called ‘critical turns’ have reassured professional historians that we are indeed inspecting our sources and our questions afresh. But as the American Historical Review authors pointed out, even critical turns can become banal. They can mask old patterns of thought that have become entrenched. However large our questions, however they have documented the construction of yet another facet of human experience – the spatial, the temporal, or the emotional – the answers of history still tended, until recently, to be marked with the common imprint: the narrow, intense focus of the Short Past.

The Short Past was not confined to social history, or indeed to the American historical profession. At around the same moment, in Cambridge, Quentin Skinner was leading a charge among intellectual historians against various long-range tendencies in the field – most notably, Arthur Lovejoy’s diachronic history of ideas and the canonical approach to ‘Great Books’ by which political theory was generally taught – in favour of ever tighter rhetorical and temporal contextualisation. This has been read as a reaction to the collapse of grand narratives in postwar Britain, notably the retreat of empire and the collapse of Christianity: ‘Focusing on context ensured a more accurate scholarship, while attempting to stay clear of any political mythology, old or new.’30 The contextualism of the so-called Cambridge School focused almost exclusively on the synchronic and the short-term settings for arguments treated as moves in precisely orchestrated language-games or as specific speech-acts, not as instantiations of timeless ideas or enduring concepts.

The contextualists’ original enemies were the Whigs, Marx, Namier, and Lovejoy, but their efforts were construed as an assault on anachronism, abstraction, and grand theory more generally. Yet Skinner’s own effort in 1985 to promote ‘the return of grand theory’ in the human sciences was beset by the paradox that many of the thinkers who inspired or represented this revanche – among them, Wittgenstein, Kuhn, Foucault, and Feyerabend – expressed ‘a willingness to emphasize the local and the contingent … and a correspondingly strong dislike … of all overarching theories and singular schemes of explanation’. Reports of the return of grand theory seemed exaggerated in the 1980s: far from returning, it was retreating into the twilight like Minerva’s owl.31 It was not until the late 1990s that Skinner himself returned to longer-range studies – of Thomas Hobbes in a tradition of rhetoric extending back to Cicero and Quintilian; of neo-Roman theories of liberty derived from the Digest of Roman law; and of conceptions of republicanism, the state, and freedom in post-medieval history – that foreshadowed a broader return to the longue durée among intellectual historians.32

From the late 1970s onwards, broad swathes of the historical profession had entered a period of retreat into short-durée studies across multiple domains, from social history to intellectual history, nearly simultaneously. Tension between the historian’s arts of longue-durée synthesis and documentary history or biography is nothing new. Shorter time-scales had, of course, a literary place before they influenced the writing of professional history. From Plutarch’s parallel Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans to Samuel Smiles’ Lives of the Engineers (1874–99), biography had formed an instructive moral substrate to the writing of history, often focusing on a purportedly diachronic category of ‘character’ visible in these exemplary life-stories.33 An emphasis on short-term history also erupted wherever history was called in to help decide between long-term visions in conflict with each other. According to Lord Acton, the acquisition of documents and the turning over of church and local archives by Michelet, Mackintosh, Bucholtz, and Migne were bound up with a desire to settle the legacy of the French Revolution, whether to understand it as ‘an alien episode’ and rebellion against natural authority or instead as ‘the ripened fruit of all history’.34 A revolution in documents resulted, where the historian’s role changed from narrative artist and synthesiser to politic critic settling controversial debates with the power of exact readings of precise documents. Institutional history, in this role, took up the task of interpreting the liberal tradition, worked out through such targeted studies of pivotal moments as Elie Halévy’s L’Angleterre en 1815 (1913). Short-term histories often focused on journalistic exposition, particular controversies, and disputed periods, for example, the poet Robert Graves’ The Long Week-End (1940), a meditation on the fading utopianism present at the beginning of the First World War revisited from the perspective of distance at the start of a second war.35

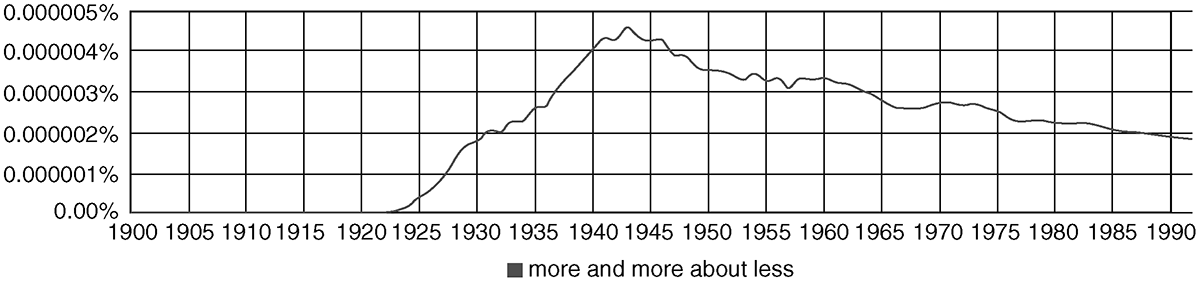

Anxiety about specialisation – about ‘knowing more and more about less and less’ – had long dogged the rise of professionalisation and expertise, initially in the sciences but then more broadly, since the 1920s (see Figure 3). Three decades later, the British novelist Kingsley Amis acutely satirised the constraints professionalisation placed on younger historians in his Lucky Jim (1953). The title character, a hapless junior lecturer in a provincial university named Jim Dixon, frets throughout the novel about the fate of the article that is meant to win him his professional spurs. The subject is ‘The Economic Influence of the Developments in Shipbuilding Techniques, 1450 to 1485’, a topic the narrator mercilessly skewers. ‘It was a perfect title’, the narrator notes, ‘in that it crystallized the article’s niggling mindlessness, its funereal parade of yawn-enforcing facts, the pseudo-light it threw upon non-problems’. Yet, within only a few years of Lucky Jim’s publication, a conscientious supervisor might have discouraged an essay on such an absurdly ambitious and wide-ranging theme.36

Figure 3 Usage of ‘more and more about less [and less]’, 1900–90

Yet never before the 1970s had an entire generation of professional historians made so pronounced a revolt against longue-durée thinking, as scholars born during the baby-boom rejected a style of writing typical of relevant, engaged historians in the generation just before their own. The works of Marxist historians, from E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963) to Eugene Genovese’s Roll, Jordan, Roll (1974), borrowed techniques from the study of folklore like the examination of ballads, jokes, and figures of speech in order to characterise working-class and slave culture and the widespread attitudinal tensions between subaltern and elite.37 That willingness to characterise grand moments shifted in the early 1970s in the work of social historians of labour like Joan Wallach Scott and William Sewell, whose work focused upon a single factory floor or patterns of interaction in a neighbourhood, and imported from sociology habits of attention to individual actors and details.38 To be sure, the focused attention of these historians was not necessarily in conflict with broader perspectives: Sewell’s study of work and revolution in France spanned decades ‘from the Old Regime to 1848’. Nor could micro-historians operate without a longue-durée framework for their thinking. Rather than writing their own long versions of history, however, historians of the Short Past tended to outsource it to German and French social theorists of the 1960s and 1970s. Michel Foucault’s centuries-long histories of sexuality, discipline, prisons, and government order offered a long-term framework sceptical of institutional progress for many a historian of fertility, education, welfare, and statistics in the Short Past, while Jürgen Habermas’ optimistic account of eighteenth-century public life offered an alternative framework.39 The prison and the coffeehouse became the two poles of macro-history, the pessimistic and the optimistic account of modern institutions, into which micro-historians of the Short Past poured their finer-grained details. Whether cited or not, these theories oriented many a detailed history of the Short Past in history, historical sociology, and historical geography.40 From 1968 to approximately 2000, many a researcher in those disciplines was thus temporarily relieved of the obligation of original thinking about the past and its significance for the future. The task of understanding shifted from generalisations about the aggregate to micro-politics and the successes or failures of particular battles within the larger class struggles.

In the decades since 1968, the Short Past has come to dominate training in thinking about time in the university. Modern textbooks geared to teach historians how to do research – at least, those published in the United States – have concentrated on the importance of narrowing questions to the specificities of the time-period. For example, Florence N. McCoy’s classic American textbook for budding historians from 1974 followed a student’s process for choosing a research paper topic. In the end, the student narrows down her topic from wanting to study Oliver Cromwell (a topic too broad for McCoy) to researching Cromwell on the union of Scotland with England. In this vision of university education, the latter topic is more appropriate than the former because it teaches the student to emulate the specialisation of a society run by experts, each of whom competes in terms of narrowness with others in their field. The paper topic on Cromwell and Anglo-Scottish union is well suited to this lesson in keeping one’s head down, because the topic ‘provides an opportunity to learn something that only the specialist in Anglo-Scots diplomatic relations knows’.41

The prejudices of the field changed alongside training. Up to the 1970s, it had been routine for historians to critique each other’s work in terms of the possible irrelevance of a subject looked at too narrowly. Those charges of narrowness were again and again levelled against young historians into the 1960s and 1970s. When they turned to periods of as little as fifty years, reviewers were wont to react. A reviewer of Paul Bew’s Land and the National Question in Ireland, 1858–82 (1979) was unimpressed to discover that the book actually confined itself to the three years between 1879 and 1882, even while he congratulated the author for his detailed study of living standards and material expectations.42 Even grand sweeps of history could be chided, when their title and introduction seemed to promise more. When Rodney Barker published a history of what he called ‘modern Britain’ but only addressed a century, his 1979 reviewer mocked him for only covering the period from 1880 to 1975, accusing the author of covering ‘too short a period’.43

But by 1979, times were changing, and the charge of ‘too short’ was not so much of a scandal. When in 1933, Arthur Schlesinger, Sr, published his history of American racial pluralism, The Rise of the City, 1878–98, the work on two decades was itself part of an ambitious multi-volume, multiple-authored attempt to chart the trajectory of America since its beginning. His introduction gave a sweeping overview of cities in Persia and Rome, but Schlesinger’s research turned upon the patterns of migration and immigration that characterised two decades around the time of his own birth. Appalled by the narrowness of temporal focus, Schlesinger’s fellow historian Carl Becker of Cornell accused him of slicing up history into periods too short to learn from. In the expanding university of the 1960s and 1970s, data were becoming more important, and Schlesinger had been elevated to canonical status. By 1965, when Schlesinger died, his Harvard colleagues were counter-accusing Becker of ‘making sweeping generalizations over long spans of history’. The official charge of failure had changed from ‘too short’ to ‘too long’.44

As the Short Past became the rule, historians increasingly ignored the art of relating deep time to the future. At least in the English-speaking world, micro-historians rarely took the pains to contextualise their short time horizons for a common reader; they were playing in a game that rewarded intensive subdivision of knowledge. In a university more intensively committed to the division of labour, there was ever less room for younger researchers to write tracts aimed at a general audience or for the deep temporal perspective which such writing often required. This was of a part with a more general retreat from grand narratives in what the American intellectual historian Daniel Rodgers has called an ‘Age of Fracture’ defined centrally by the contraction of temporal horizons: ‘In the middle of the twentieth century, history’s massive, inescapable, larger-than-life presence had weighed down social discourse. To talk seriously was to talk of the long, large-scale movements of time.’ By the 1980s, modernisation theory, Marxism, ‘theories of long-term economic development and cultural lag, the inexorabilities of the business cycle and the historians’ longue durée’, had all been replaced by a foreshortened sense of time focused on one brief moment: the here and now of the immediate present.45

In the 1980s, historians on both sides of the Atlantic began to complain that specialisation had created acute fragmentation in their field. ‘Historical inquiries are ramifying in a hundred directions at once, and there is no coordination among them … synthesis into a coherent whole, even for limited regions, seems almost impossible’, the Americanist Bernard Bailyn observed in his 1981 Presidential address to the American Historical Association (AHA). ‘The Challenge of Modern Historiography’, as he called it, was precisely ‘to bring order into large areas of history and thus to reintroduce … [it] to a wider reading public, through synthetic works, narrative in structure, on major themes’.46 Shortly afterwards, in 1985, another former AHA President, the longue-durée historian of the age of the democratic revolution, R. R. Palmer, complained of his own field of French history, ‘Specialization has become extreme … it is hard to see what such specialization contributes to the education of the young or the enlightenment of the public’.47 And in 1987 the young British historian David Cannadine similarly condemned the ‘cult of professionalism’ that meant ‘more and more academic historians were writing more and more academic history that fewer and fewer people were actually reading’. The result, Cannadine warned, ‘was that all too often, the role of the historian as public teacher was effectively destroyed’.48 Professionalisation had led to marginalisation. Historians were increasingly cut off from non-specialist readers as they talked only to one another about ever narrower topics studied on ever shorter time-scales.

Peter Novick, in his moralising biography of the American historical profession, That Noble Dream (1988), saw the 1980s as the moment when it became clear that fragmentation was endemic and ‘there was no king in Israel’. The anthropological turn, with its emphasis on ‘thick description’; the export of micro-history from Italy via France; the destabilisation of the liberal subject by identity politics and postcolonial theory; the emergent scepticism with regard to grand narratives diagnosed by Jean-François Lyotard: these were all centrifugal forces tearing the fabric of history apart.49 Yet jeremiads like those from Bailyn, Palmer, Cannadine, and Novick may have missed the central point: the disintegration of the profession was parasymptomatic of a larger trend, the triumph of the short durée.

The combination of archival mastery, micro-history, and an emphasis on contingency and context, powered by a suspicion of grand narratives, a hostility to whiggish teleologies, and an ever-advancing anti-essentialism, determined an increasing focus on the synchronic and the short-term across wide swathes of the historical profession. The stress on case-studies, individual actors, and specific speech-acts gradually displaced the long-run models of Braudel, Namier, Mumford, Lovejoy, and Wallerstein with the micro-history of Darnton, Davis, and others. Barely a decade ago, a French historian of America noted dyspeptically, ‘[a]n approach in terms of longue durée might seem old-fashioned today when postmodernism pushes scholars towards fragmented and fugacious inquiries, but it remains an asymptotic ideal we may tend toward, without being able to reach it some day’.50 However, as the founders of micro-history well understood, a history that surprises us necessarily must depend upon a critical reading of data, and often the inspection of data of many different sorts. Critical history of this kind has a public purpose to serve, one that means synthesising available data from many sources and debunking the now-flourishing illusions about our collective past and its meaning. But the Short Past needs to recover some of the forms of commitment to big questions that helped to bring it into being in 1968.

In this age of global warming and coming wars over land and water, histories of class struggles over resources and their distribution, within societies and among them, are needed now more than ever. In the last forty years, the public has embraced a series of proliferating myths about our long-term past and its meaning for the future, almost none of them formulated by professional historians. These include climate apocalypse, the end of history, and species predestination for capitalism. The long-term stories of public consumption have often been at odds with each other, as with the climate story that declares that apocalypse is imminent without government intervention and the neo-liberal story that a free market will automatically produce new forms of technology that will ameliorate the worst effects of climate change. History has the power of destabilising such overarching stories. One of the most important contributions of the Short Past was in the upsetting of mythologies of continental proportions, ones that had infected evolutionary biology, economics, anthropology, and politics to their core. It is possible to read the debates of economists debating policies for the developing world from as recently as the 1960s, and to be astounded at the invocation of race alongside historical traditions, by which we learn that India and China had an innate lack of developmental psychology in their abilities to relate to the material world and therefore to all of technology and engineering. We no longer think this way, largely because of the contributions of historians working in the decades after 1975. The myth of white racial superiority, which was revealed to have been forged with specious medical data. The myth that the American Civil War was caused by a political doctrine of states’ rights rather than the abuses of slavery. The myth of the benefits of western colonialism. The myth of western superiority. The world would be a different place right now had those various intellectual folklores not been excavated, cross-examined, and held up to the light by a generation of critical historians who had taken the cultural and postcolonial turns.

Historians no longer believe in the mythology that the world was shaped dominantly for the good of economic well-being by the influence of western empire, but many economists still do. Twenty years ago, William A. Green explained how every rewriting of history that changes when we think an event begins and ends offers an opportunity for liberation from the ‘intellectual straitjackets’ that define other fields.51 One of the prime uses of data about the past is to highlight instances of compulsive repetition, patterns that reveal themselves in the archives. Long-term data about our past stand to make an intervention in the confused debates of economists and climate scientists merely by pointing out how experts become stuck in old patterns of practice and ideology. Moreover, the digital data now being mined by climate scientists and policy analysis – the data of digitised newspapers, parliamentary records, and professional journals – are data that reflect the work of modernity’s institutions. These archives likewise support a longer durée and a thicker contextual reading than many dissertations manufactured in the last thirty years. But their longue durée is still the time-scale of decades or centuries.

An information society like ours needs synthesists and arbiters to talk about the use we make of climate data tables and economic indicators. It needs guides whose role is to examine the data being collected, the stories being told about it, and the actions taken from there, and to point out the continuities, discontinuities, lies, mismanagement, and outright confusion that occur in the process. But, above all, it needs to make those large stories comprehensible to the public it seeks to inform about future horizons and their meaning.

A sophisticated history that talks about where it gets its data has much to recommend it to a democratic society. In most of today’s university disciplines, professional training serves to distance an individual from the public, to refine them into an ‘expert’ whose speech and writing are marked by incomprehensible formulae and keywords. But history-telling came out of an age before the era of experts, and its form is inherently democratic. Like story-telling or soccer, history is an activity that every man, woman, and child has access to, which they can pursue themselves, if only through keyword search, the local history archives, or the tracing of names on old gravestones.52 Shaped into stories, that most ancient human tool for relating memory, history condenses enormous data about the past into a transmissible packet which expands into a rich brew of material for understanding things to come. Talking about the future in terms of our shared past is a method that opens up the possibility that anyone may submit an alternate position on where our future should go. They can always examine the evidence for themselves and disagree with the experts.

For example, if a complex, globalising world such as ours is to come to a position on climate change beyond the ejection of the poor to starvation or perpetual displacement and statelessness, it will need a democratic conversation about our past and possible avenues towards the future. Put to the service of the public future, history can cut through the fundamentalisms of scientists and economists who preach elite control of wealth or scientific monitoring of all earth systems as the only possible way to avoid catastrophe. History can open up other options, and involve the public in the dialogue and reimagination of many possible sustainabilities.

Popular long-term argumentation, whether about the climate, international government, or inequality, often takes the form of reasoning with many different kinds of events from long ago. A popular history like Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (2005) weaves together a gripping account of the fates of societies stricken by plague, mixing archaeological evidence with the history of species extinction and ethnic deracination. Yet even such a book lacks the level of deep engagement that was characteristic of historians of the Short Past like Natalie Zemon Davis or Robert Darnton. In their intense reckoning with archives, historians had to grapple with many kinds of data – the fairytale, the archival artifact, the book itself and its binding and illustrations. To weave stories about obscure families and individuals who had never been written about before, micro-historians became masters of using multiple kinds of evidence – archaeological, architectural, statistical, technological, economic, political, and literary – to fill in the story of how the past was lived. Micro-history and other studies in the Short Past reached heights of sophistication in the constrained inspection of experience in the past; they were masters at using data of multiple kinds. What the Short Past still must teach us is the art of looking closely at all the details, when the longest-term perspective possible is not always the most relevant. A. J. P. Taylor once quipped that looking for long-term causes was like a car driver telling a police officer that he blamed his crash on the invention of the internal combustion engine.53 When we overlook the details, questions about the big picture may slip away – no longer answered by data, but answered by speculation with the data used as marginalia.

There are few brighter examples of reductionism and its opposite than the debates over inequality in Victorian Britain, a subject that formed a major area of research for historians who grew up during the era of training in the Short Past. The Victorian period has been researched and written about in both History and Economics departments as a major concentration of the field. Yet the two fields could not disagree more about what happened. Each measures a single index or perhaps compares to indices of well-being: criminality and height; education and wealth at death; migration and wages. Based upon these data, some economists conclude that the nineteenth century led to gains in equality, opportunity, and entrepreneurship. Among economic historians dealing with inequality over the nineteenth century, a surprising number conclude that nineteenth-century industrialisation resulted in more nutrition for the poor, while twentieth-century ‘socialism’ resulted in higher taxes and stagnating social opportunity.54 According to economists, these numbers demonstrate conclusively that capitalism banished inequality during the nineteenth century, and could do so again.

From the perspective of more radical historians, the Victorian experience was characterised by police suppression, the demonisation and abuse of the poor by new political institutions, and, ultimately, by extreme efforts towards class-consciousness and political organisation on behalf of the poor and racial minorities. Rich evidence about the growth of the state and the increase in welfare provision over a century tends to suggest other measures, and a more even-handed account, sometimes challenging the state as an authoritarian source of class divides, sometimes raising questions about whether civic power from below is channelled through print technology or face-to-face speech.55 In dozens of books and articles published about the same locations and times as the economists have covered, historians have examined the diaries and pamphlets of mill workers to the accounts of food disbursed in prisons to lawsuits brought by the poor against workhouse administrators who starved or whipped them contrary to official regulations – a much denser set of evidence than the economists have looked at.56 As a result of their different modalities of collecting data, historians’ articles open up other suggestions for the future, including the importance of participatory democracy, but they very rarely confirm that the Industrial Revolution placed Victorian England on a model path towards civil accord, relative income equality, and opportunity for all.

Even the same events can be characterised in very different ways depending on how deeply layered the data are. For instance, the falling price of grain for workers during the 1870s has been celebrated by economists who model the history of growth in a 2002 paper as a demonstration that capitalism since 1500, despite deepening income inequality, ultimately created ‘real purchasing power’ for everyone, including the working class.57 That same result of cheap food has a contrasting interpretation among historians as the product, to be sure, of decades of labour organising on behalf of Manchester workers concerned about being unable to afford to eat. In fact, the moment of falling inequality around 1870 arguably had less to do with the rise of international trade, and more to do with the rise of organised labour after decades of state suppression, a moment made possible by working-class people insistently gathering in public to share their ideas and experience and organise a programme of political reform.58 That is, of course, a story about social actors; hardly a victory to be credited to the account of free-market capitalism. Yet data are abused when they are examined as a single facet of historical experience. Both positive and negative assessments from the past from economics abstract single dimensions of experience—wages, the price of grain, or height—as a proxy for freedom, democracy or happiness.59

To take a more concrete example, there is the way that historians and economists both understand progress in the British Industrial Revolution. Decades earlier, American economists performed a study of the nutrition of poor people over the course of the nineteenth century, as documented in the height and weight of individuals when first admitted to prison. The evidence seemed to suggest that poor people were earning better wages – in general, earnings in 1867 had more purchasing power than had had in 1812.60 But decades later, some British economists reconsidered the data, having spent some time reading up on British social history. The data confirmed, counter to the original thesis, that the weight of working-class women actually went down over the course of the Industrial Revolution. What we now understand is that the mothers and wives of working-class men had been starving themselves – skipping meals, passing on the bigger serving – to make sure that their mill-working or ship-loading husbands had enough energy to survive their industrial jobs. When first admitted to prison, most of the working-class women in English prisons were so thin and frail that they actually gained weight on the few cups of meagre gruel regulated by national authorities to deter lazy paupers from seeking welfare at houses of correction.61

The prison study reminds us, pace neo-liberal histories of the Industrial Revolution, of the way that class and gender privilege annihilated the victories of entrepreneurial innovation in the experience of the majority. Without a sensitivity to gender and age, the kind of sensitivity that the Cambridge economist Sara Horrell calls ‘the wonderful usefulness of history’ and attributes to her reading of historians of the Short Past, the evidence they looked at merely reinforced the prejudices of their field that Victorian industrialisation produced taller, better-fed proletarians.62 Even in the field of big data, the sensitivity to agency, identity, and personhood associated with the Short Past has much to contribute to our epistemology and method.

The inequality debate is only one example of the way that, over some thirty years, certain economic historians have clung to conclusions about the economy forged decades or centuries before. Indeed, this trend has even been evident to other economists. Journals in the field have erupted into fits, as professors file back through articles over the decades that show how their colleagues have failed to consider conflicting models in their research, for the love of a particular hypothesis or mathematical display of rigour. In 2008, economist Karl Persson flew after his colleague Greg Clark for propounding what he called ‘the Malthus delusion’ against evidence that human civilisations usually contain their reproduction, and that poverty and want are therefore due to more complex factors than over-population alone. Persson accuses Clark of cherry-picking his data, looking at cross-sections and ignoring other economic historians who have already demolished the theory: ‘When the historical record contradicts Greg Clark it is not allowed to stand in the way of his noble aim and declared intention of writing big history.’ Persson continues: ‘Clark does not surrender. Facts are not allowed to kill big history.’63 When neo-liberal economists measure one factor over time not many, they are involved in speculation not long-term thinking.

For history to be usable by the present, it needs to be small enough that historians can do what they do best: comparing different kinds of data side by side. In traditional history, multiple causality is dealt with under the heading of different aspects of history – intellectual history, art history, or history of science – which reflect a reality forged by many hands. The reality of natural laws and the predominance of pattern do not bind individuals to any particular fate: within their grasp, there still remains an ability to choose. An historical outlook reminds the public that there are multiple causes at work for any event in the past – and as a result, that more than one favourable outcome is possible in the future.