Book contents

- The Impossible Office?

- Works by Anthony Seldon

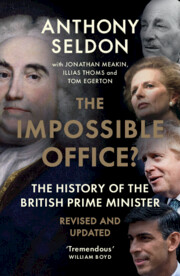

- The Impossible Office?

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 The 300th Anniversary Bookend Prime Ministers

- Chapter 2 A Country Transformed, 1721–2024

- Chapter 3 The Liminal Premiership

- Chapter 4 The Transformational Prime Ministers, 1806–2024

- Chapter 5 The Powers and Resources of the Prime Minister, 1721–2024

- Chapter 6 The Constraints on the Prime Minister, 1721–2024

- Chapter 7 The Eclipse of the Monarchy, 1660–2024

- Chapter 8 The Rise and Fall of the Foreign Secretary, 1782–2024

- Chapter 9 The Rise, and Rise, of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1660–2024

- Chapter 10 The Impossible Office?

- Acknowledgments to the First Edition

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Chapter 1 - The 300th Anniversary Bookend Prime Ministers

Walpole and Johnson

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2024

- The Impossible Office?

- Works by Anthony Seldon

- The Impossible Office?

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 The 300th Anniversary Bookend Prime Ministers

- Chapter 2 A Country Transformed, 1721–2024

- Chapter 3 The Liminal Premiership

- Chapter 4 The Transformational Prime Ministers, 1806–2024

- Chapter 5 The Powers and Resources of the Prime Minister, 1721–2024

- Chapter 6 The Constraints on the Prime Minister, 1721–2024

- Chapter 7 The Eclipse of the Monarchy, 1660–2024

- Chapter 8 The Rise and Fall of the Foreign Secretary, 1782–2024

- Chapter 9 The Rise, and Rise, of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1660–2024

- Chapter 10 The Impossible Office?

- Acknowledgments to the First Edition

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

This chapter analyses the first prime minister, Robert Walpole, against Boris Johnson – the prime minister at the time of the office’s 300th anniversary. The two PMs bookend 300 momentous years of history, but what has changed about the office of prime minister? Comparing personal and political, the chapter examines the machinery of government, from patronage in Parliament to departmental power as well as the core driver for the role of prime minister. While the country and office have changed, some core functions and political realities remain the same in the British system.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Impossible Office?The History of the British Prime Minister - Revised and Updated, pp. 1 - 29Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024