9.1 Introduction

In this article, prepared for a special JCLE symposium, I revisit my initial findings regarding the prevalence of ‘horizontal directors’ in the United States.Footnote 1 ‘Horizontal directors’ serve on the board of multiple companies operating within the same industry. I have previously spotlighted the prevalence of horizontal directors in the US, despite a prima facie prohibition on director service among competitors.

Despite that spotlight and increasing attention to common ownership and to director interlocks, this Article explores six additional data years to further demonstrate the prevalence of horizontal directors as recently as the end of 2019.

In fact, in this project, the original dataset has been enhanced with bookend data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019 for the director-level analysis. These expanded data confirm the rise of horizontal directors previously discussed and highlight their continued prevalence even against a backdrop of increased attention to the effects of common ownership and directors’ interlocks.

Horizontal directors are significant because they stand at a unique intersection of antitrust law and corporate governance. They offer many legitimate governance and operational benefits to companies and shareholders but at the same time pose significant concerns both to the governance of the corporation and to antitrust policy. Despite that significance, horizontal directors have yet to receive the proper attention from regulators, stock exchanges, and investors.

This lack of attention to the horizontal aspect of director interlocks is particularly surprising for two reasons. First, existing US antitrust regulation specifically prohibits directors from serving on the boards of two competitors,Footnote 2 so sharing a director across companies in the same industry may violate these laws. Second, antitrust law has re-emerged in recent yearsFootnote 3 commanding increased attention to market concentration and consumer welfare (specifically in merger decisionsFootnote 4 and ‘horizontal shareholding’Footnote 5 by institutional investors). This emerging literature has sparked a vivid academic and public debate regarding the effects of shareholder concentration on antitrust policy.Footnote 6 Specifically, scholars have raised concerns regarding the incentives of companies to compete where major institutional shareholders hold large equity positions in all competitors. While market concentration by large investors has been widely acknowledged, a vivid debate has ensued on whether such concentration materialises in ways that promote anticompetitive behaviour.Footnote 7 As a by-product of this debate, recent focus has been directed to the question of which channels common owners use to effect anticompetitive behaviour.

For instance, one channel prominently discussed in recent years is executive compensation. Some suggest that common owners may either actively discourage performance-sensitive compensation or not actively push for a particular compensation plan and instead promote the status quo which lets executives ‘get away with high performance-insensitive pay’.Footnote 8 While less plausible, another channel is through a targeted strategy of specific actions that is communicated to management that promotes portfolio value even at the expense of firm value.Footnote 9 In this channel, a common owner obtains leverage over management with its voting power and its ability to sell shares and decrease the market price of firm stock in order to promote its strategy.Footnote 10 Interestingly, and surprisingly, the role of directors as potential conduits of common ownership has been left underexplored. Specifically, horizontal directors might create this exact channel for common owners’ influence, therefore facilitating anticompetitive effects on the market.Footnote 11 Alternately, horizontal directors may alone serve as the channel through which anticompetitive practices are achieved, without the need to pin such results on common owners.Footnote 12

Equally important, horizontal directors are not a rarity: in fact, as shown below, empirical data reveal hundreds of directors concurrently serving on boards of companies operating in the same or similar industries. More so, the prevalence of horizontal directors is on the rise. Yet, despite the rise in horizontal directorships over time, proactive corporate disclosure of horizontal directors remains sparse.Footnote 13 Notably, the presence of horizontal directors across industry lines is not equal. Some industries are more prone to having horizontal directors than others. For example, while the construction industry has on average 10.6% industry-level horizontal directors serving on two or more companies’ boards, the manufacturing industry has 33.7%.Footnote 14 This variance across industries invites for further research trying to connect industry levels of anticompetitiveness and horizontal directorships.

This Article proceeds as follows. Part II starts by providing an overview of the unique case of horizontal directors. Part III then provides a refreshed empirical analysis of the S&P 1500 director dataset and also revisits the company-level analysis of disclosure practices. Part IV then provides an overview of the current US legal framework governing and regulating horizontal directors. Part V discusses and analyses the implications of those results in more detail in light of the potential benefits and concerns horizontal directors may bring.

9.2 From Interlocks to Horizontalness

Directors’ service on multiple boards has drawn both investor and academic attention,Footnote 15 mostly focusing on one of two areas: (1) the number of board seats a director holds and whether directors who hold several board positions have an impact on company performance or other governance metricsFootnote 16 or (2) the ‘interlocks’, or the connections and bridges, created between two (or more) companies by having a director that serves on both (or multiple) boards.Footnote 17

Busy directors, and the interlocks they create, are a natural and inevitable by-product of a corporate culture that taps directors to serve on multiple boards at once.Footnote 18 The benefits of serving on multiple boards are tangible. Busy directors have more experience, provide more connections and develop more industry expertise at a rate that exponentially increases with the number of boards they serve.Footnote 19 Conversely, less-busy directors provide fewer tangential benefits derived from busyness to firms.Footnote 20

While there is no shortage in attention to busy directors,Footnote 21 missing from current discourse is a more nuanced account of the boards on which busy directors serve. While by definition directors serving on more than one board fall into the definition of a ‘busy director’, some of these busy directors also serve on more than one board in the same industry – these are what I termed as horizontal directors.Footnote 22

Horizontal directors are particularly important because their prevalence, as discussed below, raises both governance and antitrust concerns. Horizontal directors raise antitrust concerns since their concurrent board seats provide a channel between companies in the same industry. These channels can lead to either collaboration and/or collusion.Footnote 23 Additionally, horizontal directors also raise corporate governance concerns, such as reduced independence and increased conformity in governance practices that could lead to systemic governance risk.Footnote 24 Moreover, the rise in horizontal directors comes against a backdrop of heightened concentration in the US markets. More than 75% of US industries experienced a rise in concentration levelsFootnote 25 in recent years.Footnote 26 As the distribution of a given market among participating companies becomes less spread out, the anticompetitive effects of collusion and price-fixing intensify. Therefore, the potential impact of horizontal directors is also amplified.

A final factor contributing to the profound effect horizontal directors can have in the corporate landscape is a product of the fact that demarcation lines among industries are becoming increasingly more difficult to ascertain.Footnote 27 Because horizontal directors are identified based on industry, the murkier industry lines become, the harder it will be to identify and monitor horizontal directors for anticompetitive behaviour.

9.3 Revisiting Horizontal Directors: Empirical Findings

This Part provides augmented data on the prevalence of horizontal directors in the US as well as information disclosed to investors on horizontal directors. The data presented herein extend prior analysis,Footnote 28 expanding the analysis to include data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019, therefore providing an even more broad view of the rise of director horizontalness and the persistence of it even as recently as January 2020.

9.3.1 Horizontal Directors in S&P 1500 Companies

9.3.1.1 Methodology

This Part examines the prevalence of horizontal directors on boards in the same industry for companies within the S&P 1500 from 2007 and through 2019. The data for this sample were originally compiled from Equilar’s BoardEdge dataset.Footnote 29 Both director-level data and company-level data were obtained for each company within the S&P 1500 for each year previously mentioned. These separate datasets were merged to create one panel dataset at the director-company-year level where each individual case describes a director’s service on a specific S&P 1500 board as well as any additional boards that specific director served on and that were outside of the S&P 1500. For the purposes of analysis all directors were included, whether they were designated as independent or not. This consolidated dataset was subsequently supplemented with company-level data from FactSet and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Association to add NAICS codesFootnote 30 and industry classifications for groups of SIC and NAICS codes.

Directors were coded as ‘horizontal’ using four classifications: whether a director served on more than one board in the same (1) SIC code, (2) SIC industry, (3) NAICS code, or (4) NAICS industry. Because an ‘industry’ contains multiple SIC codes or NAICS codes, the industry-horizontal classifications are a broader measure than the classifications based on specific SIC or NAICS codes. However, using both SIC and NAIC classifications allows for a more robust analysis. Directors were given a binary variable (0 or 1) for each classification indicating their horizontal status. These variables were used to calculate the number of horizontal boards on which the director served in a given year. Directors were also coded as ‘busy’ – serving on more than one board at a time – regardless of whether those boards are horizontal. Each busy director was individually coded with an indicator variable as well as a count of the number of boards on which they served each year.

9.3.1.2 Director-Level Analysis

As depicted in Table 9.1, the expanded data show the number and percentage of directors in the S&P 1500 who served on more than one board. From 2007 to 2019, more than 30% of all directors sat on more than one board, and a substantial number of directors (around 12%) held three or four board positions. The data covering the 2010–2016 years (‘The Original Data’) pointed out that the percent of busy directors did not vary more than 2% from 2010 to 2016. However, the supplemented data from 2007 to 2009 and 2017 to 2019 show a more prominent incline in busy directors over time. For example, the number of directors that served on two boards increased by 17% from 2007 to 2019, and the number of directors that served on three boards increased by 39% for this same time period.

Table 9.1 Number of boards a director sits on

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7+ | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2019 | 61.93% | 24.99% | 9.21% | 3.11% | 0.63% | 0.09% | 0.04% | 100.00% |

6,159 | 2,485 | 916 | 309 | 63 | 9 | 4 | 9,945 | |

2018 | 60.81% | 24.91% | 10.14% | 3.22% | 0.75% | 0.12% | 0.05% | 100.00% |

6,175 | 2,530 | 1,030 | 327 | 76 | 12 | 5 | 10.155 | |

2017 | 60.42% | 25.08% | 10.43% | 3.16% | 0.78% | 0.09% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

5,943 | 2,467 | 1,026 | 311 | 77 | 9 | 3 | 9,836 | |

2016 | 65.14% | 22.44% | 9.08% | 2.66% | 0.52% | 0.10% | 0.04% | 100.00% |

8,191 | 2,822 | 1,142 | 335 | 66 | 13 | 5 | 12,574 | |

2015 | 63.75% | 23.49% | 9.05% | 2.92% | 0.59% | 0.13% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,937 | 2,925 | 1,127 | 363 | 74 | 16 | 9 | 12,451 | |

2014 | 63.55% | 23.37% | 9.22% | 2.83% | 0.79% | 0.18% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,960 | 2,927 | 1,155 | 354 | 99 | 22 | 9 | 12,526 | |

2013 | 63.31% | 23.28% | 9.78% | 2.70% | 0.70% | 0.17% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,822 | 2,877 | 1,208 | 333 | 86 | 21 | 9 | 12,356 | |

2012 | 63.92% | 23.24% | 9.40% | 2.44% | 0.78% | 0.14% | 0.07% | 100.00% |

7,755 | 2,820 | 1,141 | 296 | 95 | 17 | 8 | 12,132 | |

2011 | 64.23% | 23.25% | 9.11% | 2.44% | 0.75% | 0.19% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

7,650 | 2,769 | 1,085 | 291 | 89 | 23 | 3 | 11,910 | |

2010 | 63.63% | 23.41% | 9.20% | 2.68% | 0.74% | 0.30% | 0.03% | 100.00% |

7,564 | 27,83 | 1,094 | 318 | 88 | 36 | 4 | 11,887 | |

2009 | 72.88% | 18.76% | 6.03% | 1.71% | 0.50% | 0.12% | 0.01% | 100.00% |

10,090 | 2,597 | 835 | 237 | 69 | 16 | 1 | 13,845 | |

2008 | 71.60% | 19.88% | 6.35% | 1.56% | 0.49% | 0.11% | 0.02% | 100.00% |

10,164 | 2,822 | 902 | 221 | 69 | 15 | 3 | 14,196 | |

2007 | 69.60% | 21.35% | 6.64% | 1.80% | 0.47% | 0.11% | 0.02% | 100.00% |

9,675 | 2,968 | 923 | 250 | 66 | 15 | 3 | 13,899 |

Additionally, the percent of directors that serve on two or more boards has increased despite the fact that the total number of directors in the sample has decreased by 3% on average each year (total decline of 28% from 2007 to 2019).

As I have previously underscored, horizontal directors are not outliers among directors of public companies – the opposite is true. Table 9.2 shows that the trends previously highlighted with respect to the Original Data are amplified by the additional years included. Although the data show that the percent of busy directors that share an industry within their boards served does not vary more than 8% in this 13-year period, a closer look at the data shows more nuanced patterns. For example, the number of directors that served on boards of at least two companies within the same industry slowly increased from 2007 to 2009. However, from 2009 to 2010 there was a 20% decrease in the number of directors that served on two or more boards within the same industry, showing some year-to-year volatility in the appointment of horizontal directors.

Table 9.2 Number and percentage of busy directors sharing an industry within boards served

# of boards | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2 | 895 (34%) | 994 (35%) | 1473 (46%) | 952 (34%) | 1002 (36%) | 1056 (37%) | 1077 (37%) | 1094 (37%) | 1075 (37%) | 1051 (37%) | 936 (38%) | 960 (38%) | 954 (38%) |

3 | 519 (62%) | 571 (63%) | 618 (65%) | 676 (62%) | 687 (63%) | 724 (63%) | 800 (66%) | 769 (67%) | 751 (67%) | 767 (67%) | 675 (65%) | 674 (65%) | 596 (65%) |

4 | 197 (79%) | 184 (78%) | 266 (83%) | 258 (81%) | 237 (81%) | 237 (81%) | 267 (80%) | 289 (82%) | 300 (83%) | 282 (84%) | 262 (84%) | 281 (85%) | 269 (86%) |

5 | 63 (90%) | 62 (90%) | 97 (92%) | 80 (91%) | 81 (91%) | 89 (94%) | 79 (92%) | 93 (94%) | 67 (91%) | 62 (94%) | 75 (95%) | 73 (95%) | 56 (90%) |

6 | 16 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 25 (93%) | 33 (92%) | 22 (96%) | 16 (94%) | 21 (100%) | 22 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

7+ | 1 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (67%) | 4 (80%) | 3 (75%) |

Although industry classification is broader than a single SIC or NAICS classification, combining multiple codes, the number of horizontal directors is substantial under both metrics. There were 1,888 directors that served on the board of more than one company within the same industry in 2019. On a more granular level, there were 412 directors (10.8% of directors serving on more than one board) who served on at least two companies in the same industry per four-digit SIC code. Similarly, there were 250 directors (9.2% of the directors serving on more than one board) that served on at least two companies’ boards within the same NAICS code.

The number of directors that serve on more than one company with the same NAICS or SIC code has decreased by only 3% from 2016 to 2019 (Table 9.3). Therefore, there has not been a significant change in the striking presence of horizontal directors since the Original Data.

Table 9.3 Number and percentage of busy directors sharing SIC/NAICS within boards served

# of boards | SIC/NAICS | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2 | SIC | 140 (5%) | 149 (5%) | 180 (6%) | 183 (6%) | 195 (7%) | 208 (8%) | 209 (8%) | 170 (7%) | 169 (7%) | 184 (7%) |

NAICS | 104 (4%) | 120 (4%) | 144 (5%) | 155 (5%) | 165 (6%) | 159 (5%) | 147 (5%) | 143 (6%) | 151 (6%) | 156 (6%) | |

3 | SIC | 101 (9%) | 103 (9%) | 123 (11%) | 139 (12%) | 129 (11%) | 148 (13%) | 150 (13%) | 146 (14%) | 154 (15%) | 129 (14%) |

NAICS | 80 (7%) | 81 (7%) | 99 (9%) | 118 (10%) | 115 (10%) | 129 (11%) | 132 (12%) | 121 (12%) | 123 (12%) | 107 (12%) | |

4 | SIC | 45 (14%) | 43 (15%) | 53 (18%) | 70 (21%) | 68 (19%) | 85 (25%) | 102 (29%) | 73 (23%) | 77 (23%) | 67 (21%) |

NAICS | 36 (11%) | 40 (14%) | 41 (14%) | 57 (17%) | 65 (18%) | 62 (17%) | 56 (17%) | 65 (21%) | 65 (20%) | 63 (20%) | |

5 | SIC | 21 (24%) | 19 (21%) | 28 (29%) | 28 (33%) | 31 (31%) | 24 (32%) | 26 (39%) | 38 (48%) | 29 (38%) | 22 (35%) |

NAICS | 14 (16%) | 14 (16%) | 28 (29%) | 23 (27%) | 23 (23%) | 19 (26%) | 24 (36%) | 35 (44%) | 23 (30%) | 14 (23%) | |

6 | SIC | 13 (36%) | 8 (35%) | 9 (53%) | 8 (38%) | 13 (59%) | 9 (56%) | 10 (77%) | 7 (78%) | 7 (58%) | 9 (90%) |

NAICS | 13 (36%) | 10 (43%) | 7 (41%) | 5 (24%) | 11 (50%) | 7 (44%) | 8 (62%) | 5 (56%) | 6 (50%) | 9 (90%) | |

7+ | SIC | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (62%) | 7 (78%) | 6 (67%) | 4 (44%) | 2 (40%) | 2 67%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (25%) |

NAICS | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (62%) | 6 (67%) | 5 (56%) | 3 (33%) | 2 (40%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (25%) | |

Total | SIC | 321 (7.4%) | 322 (7.5%) | 398 (9.2%) | 435 (9.5%) | 442 (9.7%) | 478 (10.5%) | 499 (11.3%) | 436 (11.1%) | 449 (11.2%) | 412 (10.8%) |

NAICS | 248 (5.7%) | 265 (6.2%) | 324 (7.5%) | 364 (8%) | 384 (8.4%) | 379 (8.3%) | 369 (8.4%) | 371 (9.5%) | 371 (9.2%) | 350 (9.2%) |

Table 9.4 further shows that the percentage of horizontal directors as a percent of busy and total directors has been trending upwards over time with a merely a slight decline seen in the last two years. For example, in 2010, 7.4% of all horizontal directors sat on at least two boards of within the same SIC classification. This number increased by 7% on average each year from 2010 to 2016 but decreased by 2% in both 2018 and 2019. A similar trend was observed under the NAICS classification with an average increase in that metric of 8% each year with a decline of 3% in the last two years.

Table 9.4 Time trend of horizontal directors

Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

% of Industry-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.6 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 17.8 | 17.3 | 19.7 | 19.5 | 18.8 |

% of Industry-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 46.3 | 47.7 | 48.7 | 49.7 | 49.8 | 49.1 | 49.7 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 49.6 |

% of SIC-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

% of SIC-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 7.4 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11 | 10.8 |

% of NAICS-Horizontal Directors out of All Directors | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

% of NAICS-Horizontal Directors out of Busy Directors | 5.7 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 8 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 |

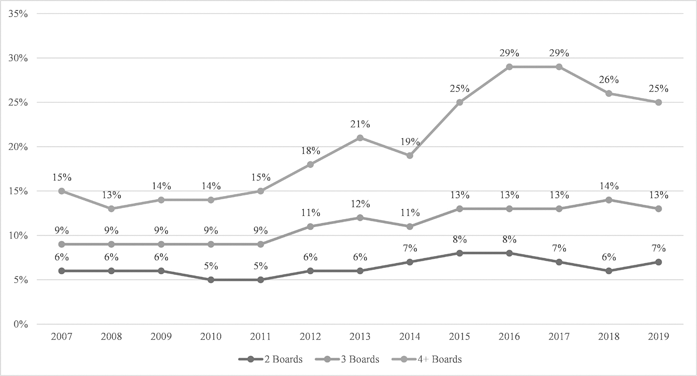

The pattern of steady growth followed by a slight decline is magnified in Figure 9.1. As depicted below, there has been a significant amount of growth from 2007 to 2016, particularly among directors serving on three or more boards. However, the expanded data show that the number of busy directors who sit on boards for companies within the same SIC code has slightly decreased in the last couple of years especially for directors serving on four or more boards, though it is still at significantly higher levels compared to 2010.

Figure 9.1 Percentage of busy directors sitting on at least two boards with the same SIC code

9.3.2 Disclosure Practices

The SEC imposes disclosure requirements on publicly traded companies in regard to their independent directors. Under Item 407 of Regulation S-K, companies are required to disclose which directors have been determined to be independent by the board of directors.Footnote 31 Companies must also disclose any non-independent members of the compensation, nominating, or audit committees.Footnote 32 And lastly, if any company has adopted its own director independence standards, in addition to the existing stock exchange rules, the company must disclose whether its own definition of ‘independence’ is available online.Footnote 33

Alongside the director independence disclosure requirements, companies are required to provide general information on their directors. Notably, Item 401(e)(2) requires companies to ‘[i]ndicate any other directorships held, including any other directorships held during the past five years, held by each director’.Footnote 34 Thus, Items 401 and 407 collectively require companies to disclose which directors are considered independent and to detail each director’s position on the board and any directorships held over the past five years.

The disclosure of board positions enables investors to better monitor and influence companies regarding board composition, including horizontal directors. However, companies vary in their disclosure practices and many lack several elements that would give shareholders access to information about horizontal directors.

To analyse the disclosure practices for companies within different market capitalisations, data were hand collected for fifty large-cap companies that make up the Fortune 50 and fifty small-cap companies that make up the Russell 2000. Data regarding the service of directors for other companies were collected from each company’s most recent form DEF 14A – an annual proxy filing required by the SEC.

Of the 100 companies surveyed, 99 had directors that served on another board. 97 of those companies disclosed this information, but only 24 of those companies provided a description of the other company or identified the company’s industry, as shown in Table 9.5. As previously noted, given the scarcity of information disclosed, it is very difficult to ascertain the presence of a horizontal director.

Table 9.5 Director disclosures

Level of proxy statement disclosure | Percent of companies |

|---|---|

Name of other boards served | 97 |

Industry of other boards served | 24 |

Current boards served | 95 |

Past boards served | 90 |

More than minimum disclosure of past five years | 53 |

Additionally, companies are only required to disclose a director’s prior roles for the last five years. Considering many companies (53%) only disclose the minimum required and some (6%) didn’t disclose any past information at all, this causes a great concern as the social and professional ties that a director develops while serving on other boards generally last for much longer than five years. Even when this information was disclosed, it is often buried within a paragraph and not presented in an easy-to-digest format that highlights this information. This leaves shareholders in the dark about the true prevalence of horizontal directors in their portfolio companies.

9.4 The Peculiar Presence of Horizontal Directors

9.4.1 The Regulatory Framework

Horizontal directorships are not completely unchecked, they are subject to several regulatory and market restrictions. While corporate and securities laws do not explicitly prohibit horizontal directorships,Footnote 35 a mosaic of regulatory and market-based restrictions does provide outer limits on their prevalence. Similarly, and more explicitly, antitrust laws attempt to target collusion between competitor companies with common directors.Footnote 36 Yet, these constraints may have not yielded the expected results. Indeed, despite the various constraints on horizontal directors, they remain prevalent.

9.4.1.1 Antitrust: Section 8 of the Clayton Act

The major aim of antitrust regulation is to promote healthy, fair, and robust competition among companies.Footnote 37 Horizontal directors may provide an avenue for companies to collude at the expense of consumers, in direct violation of antitrust regulatory goals.Footnote 38 Section 8 of the Clayton Act directly addresses this concern by prohibiting an individual or entity from serving on the board or as an officer of two competing corporations.Footnote 39 The crux of Section 8 revolves around the requirement that the two companies be competitors. Horizontal directors risk violating Section 8 if the two (or more) companies in question are considered ‘competitors’, as the Clayton Act requires.Footnote 40 Companies that produce the same products, companies that sell ‘reasonably interchangeable products within the same geographic area’,Footnote 41 and ‘companies that vie for the business of the same prospective purchasers, even if the products they offer, unless modified, are sufficiently dissimilar to preclude a single purchaser from having a choice of a suitable product from each’ all fall into the category of ‘competitors’ for purposes of Section 8.Footnote 42

The government can also target horizontal directors under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act) as an unfair practice or method of competition,Footnote 43 which provides the FTC with broader power to pursue per se violations and activities that violate the spirit of the Clayton Act.Footnote 44 It follows that horizontal directors do not have to overtly collude to violate antitrust law. The FTC recently demonstrated that anticompetitive effects outside of direct coordination could still violate antitrust principles, relying on evidence of unilateral effects.Footnote 45 Interestingly, horizontal directors are also prevalent in the EU.Footnote 46 However, unlike the US, horizontal directors in direct competitors are not prohibited in Europe, with the exception of Italy.Footnote 47 Italy prohibited interlocking in 2011 to promote competition in the banking, insurance, and financial sectors.Footnote 48

9.4.1.2 Fiduciary Duty Law

Directors are agents of the corporation, and therefore, they owe fiduciary duties to the corporation.Footnote 49 Because horizontal directors serving on the board of two companies owe concurrent fiduciary duties to each company, they are at a heightened risk of violating their fiduciary duties.Footnote 50

Delaware law has well-developed case law interpreting allegations of conflicting loyalties and corporate opportunity violations.Footnote 51 Loyalty conflicts typically arise in the parent–subsidiary setting. Delaware courts have declined to hold that dual-seated directors on parent–target subsidiary boards are per se conflicted,Footnote 52 but have found a violation of good faith and fair dealing and the ‘absence of any attempt to structure [the] transaction on an arm’s length basis’, and on that basis held that the directors were conflicted.Footnote 53

Additionally, under the corporate opportunity doctrine, directors may not take for themselves ‘a new business opportunity that belongs to the corporation, unless they first present it to the corporation and receive authorization to pursue it personally’.Footnote 54 Horizontal directors are more susceptible to potential corporate opportunity concerns due to their increased access to intra-company information.Footnote 55 The potential for these directors to, even unintentionally, violate their fiduciary duties is reason for them to limit their service on other boards, or at the very least restrict their exposure through corporate opportunity waivers,Footnote 56 recusals, and nondisclosure agreements.Footnote 57

9.4.1.3 Interlocking Director Committee Limitations

Horizontal directors are theoretically also restricted by The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the NASDAQ Stock Market, both of which require that a majority of a company’s board of directors be independent.Footnote 58 Because director independence can depend on the director’s or her family members’ service in other companies, a horizontal director who serves on the board of multiple companies risks corroding her independence.Footnote 59

A specific restriction imposed by the NYSE that could impact the service of horizontal directors requires that simultaneous service on more than three public company audit committees be disclosed and approved by the board.Footnote 60 NASDAQ does not have the same rule, but in recent years there has been a marked drop-off in participation on more than three audit committees by directors.Footnote 61 As Table 9.6 demonstrates, the percentage of directors serving on the audit committees on four or more boards has declined dramatically, going from 8.33% in 2010 to 0.51% in 2019.

Table 9.6 Audit committee participation by busy directors

Audit participation | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

4+ Boards | 8.33% | 9.09% | 6.06% | 2.90% | 2.33% | 1.87% | 1.80% | 0.54% | 0.54% | 0.51% |

9.4.1.4 ISS/Glass Lewis

Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. (ISS) and Glass Lewis wield influence in potentially comparable ways to that of governmental regulators by shaping corporate governance practices and corporate board policies.Footnote 62 Both ISS and Glass Lewis have adopted policies providing additional boundaries on the service of directors on multiple boards that companies will be expected to follow in order to win the support of ISS and Glass Lewis.

Because support of these proxy advisory firms is critical, their adopted policies likely increase the pressure on firms to reduce the number of busy directors, including horizontal directors. Even though their policies only serve as an outer limit on extreme cases of horizontal directorships and are unlikely to curb a large percentage of the cases, these standards still have an impact. As Part II demonstrated, the ratio of horizontal directors dramatically increases as they serve on more boards. Therefore, limiting – even modestly – the number of boards on which a director can hold a position has a stronger impact on those directors that have horizontal directorships.

9.4.1.5 Disclosure Rules

Finally, as discussed above, the SEC imposes disclosure requirements on publicly traded companies requiring them to provide general information on their directors, including information regarding their service on other boards. To the extent companies comply with such requirements, it may deter them from appointing horizontal directors if they anticipate regulatory pressure or investor push-back.

9.4.2 Horizontal Directors: Contrasting the Law with the Data

Antitrust laws prohibit horizontal directorships in competing corporations. Yet, as discussed herein, a significant number of directors serve on boards in the same industry, even if narrowly defined by NAICS and SIC classifications. While industry measures are only a crude proxy for the potential of two companies to compete, it is more likely that two companies operating in the same space will in fact compete. This is especially true given the wide definition of competition that has been applied to Section 8.Footnote 63 How can one explain this disparity of law and reality?

As I discussed in a prior writing, there are several key factors that help explain the prevalence of horizontal directors against this regulatory backdrop. First, it could be that companies sharing a director, even in the same industry, are not competitors, and therefore are not in violation of Section 8. However, this is unlikely given the fact that Section 8 applies to ‘companies that vie for the same purchasers’ even if dissimilar products.Footnote 64 Second, although Section 8 is a strict liability offense,Footnote 65 several practical and structural barriers hinder its enforcement. Historically, the FTC and DOJ have not brought Section 8 enforcements in court,Footnote 66 but instead have relied on self-policing and behind-the-scenes actions to pressure violators.Footnote 67 Additionally, private plaintiffs may be disincentivised from bringing a claim due to the lack of remuneration for individual shareholders, especially in cases where horizontal directors advance shareholder value. Furthermore, as discussed above, information regarding horizontal directors is not clearly disclosed or readily available to shareholders to identify these situations.Footnote 68

Section 8 also gives the FTC a lot of discretionary power and lacks clarity and a bright-line rule in applying the ‘competition’ requirement. This is further complicated by the fact that it is not always obvious to discern the market in which a company operates. The lack of a clear and public enforcement process adds a layer of difficulty in projecting FTC/DOJ enforcement and in deterring companies from violating Section 8 ex-ante.

9.5 Horizontal Directors: Zero-Sum Proposition?

Some level of collaboration between companies within the same industry can be beneficial to consumers; therefore, antitrust laws only target efforts that lead to anticompetitive outcomes or collusion.Footnote 69 Horizontal directors may provide value to the company and investors, such as contributing to the diffusion of beneficial corporate governance practices, networking, and expertise. By sitting on boards of multiple companies in the same industry, horizontal directors gain intimate knowledge can be a valuable asset to a director’s ability to advise and monitor the management team.Footnote 70 However, the presence of horizontal directors also presents concerns, such as an increased risk of antitrust collaboration, an increased risk of systemic governance risk,Footnote 71 and decreased director independence.Footnote 72 Furthermore, horizontal directors may facilitate anticompetitive practices that could further insulate management from market pressures which may lead to a loss of shareholder value in the long term.

As previously explored, this Article re-emphasises the need to shine a spotlight on horizontal directors and to address the accompanying concerns. Even though there has been a slight decline in the number of directors serving on companies within the same industry in the last few years, the overall prevalence of horizontal directors remains a concern.

Yet, horizontal directors are not necessarily a zero-sum proposition. Companies could still tap the valuable aspects of horizontal directors while at the same time minimising the concerns that they may present.

First, legislation that targets higher risk companies will be more effective at mitigating antitrust risks and will be easier to enforce uniformly, which will mitigate some of the current Section 8 underenforcement concerns. As I previously discussed,Footnote 73 some industries and SIC codes are more likely to have horizontal directors, and some of these horizontal-director-saturated industries also exhibit strong levels of industry concentration, perhaps making them a key starting point for evaluation.

Focusing the prohibition on concentrated industries might strike a desired balance. The right balance would allow companies to enjoy the benefits these directors provide while prohibiting their presence in cases where the costs to competition are more likely to outweigh these benefits. For instance, Section 8 could be revised to exempt from the prohibition industries with an HHI that is below a certain threshold. Aggressively enforcing Section 8 for that subset of public companies would reduce significant antitrust risk. Italy took a similar approach, in focusing on the banking sector. The main provision dealing with interlocking directors prohibits members of boards and any top manager of a company operating in the banking, insurance, and financial sectors from holding one of those offices in a competing company.Footnote 74 However, the Italian legislation was criticised for its inflexibility and lack of clarity.Footnote 75 For example, the Act did not include a de minimis exemption for very small firms that did not prompt the same concerns as larger companies.Footnote 76 If policymakers choose to amend the Clayton Act, they should take care to incorporate flexibility to strike the desired balance.

Second, regulators could consider an ex-ante design to Section 8 of the Clayton Act that would allow directors to apply for a waiver before accepting a horizontal directorship. By obtaining an ex-ante ‘no action’ waiver,Footnote 77 companies would be more certain about nominating potential directors. Furthermore, companies would be able to justify the nomination of directors that would technically violate the Act. Giving the FTC a veto right ex-ante would also reduce the need for costly ex-post enforcement and may lead to more consistent enforcement.

In fact, a similar arrangement is already employed in the context of interlocking bank directorships. The Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) Regulation L is similar to the Clayton Act in that it prohibits an officer or director of a bank from serving as an officer or director for more than one of any bank’s holding companies with over $10 billion in assets.Footnote 78 However, Regulation L allows the Fed to grant waivers when it determines that an interlock would not substantially lessen competition.Footnote 79 While the banking industry is more regulated than other industries, one can easily find ways to implement this rule in a cost effective way across other industries. For instance, the FTC may require a public notice to be filed, with a presumption of approval unless otherwise indicated within 20 days. The notice in turn will also allow shareholders, stock exchanges, and proxy advisors to apply private ordering restrictions if they so desire.

Third, and as previously mentioned, horizontal directors toe the line between antitrust and corporate governance, and a comprehensive reform should highlight the benefits of these directors as well as address the corporate governance risks. As Part II highlighted, many companies currently keep disclosures to the bare minimum required.Footnote 80 Thus, it is often difficult to even identify the industry of the other boards on which horizontal directors serve. Regardless of whether shareholders see horizontal directors as positively or negatively impacting the company, improved transparency via more comprehensive disclosures would enable shareholders to more effectively participate in corporate governance by making more informed director nominations and board recommendations.

An alternative approach to consider for reform would be updating stock exchanges’ self-regulation to better incorporate horizontal directorship concerns. One concern of horizontal directorships is the ability of directors to serve as independent directors when they have extensive experience in one industry. From a shareholder perspective, including directors with deep industry experience may add significant value to the company. Accordingly, stock exchanges may consider revising their independence definitions to exclude directors from being considered independent if they serve on the boards of two companies in the same SIC code, whether or not they are considered competitors. This restriction could strike a better balance between enabling companies from benefitting from horizontal directorship and preventing boards and directors from becoming too dependent on their specific industry connection.

Finally, state law and fiduciary law can also evolve to increase restrictions to mitigate the concerns that arise from the prominence of horizontal directors. Additionally, tightening judicial review of non-compete agreements, corporate opportunity waivers, and board fiduciary duties may position common law jurisprudence to more effectively address potential governance issues that stem from the presence of horizontal directors. For example, courts may examine corporate opportunity waivers more skeptically where a horizontal director is involved and where the opportunity is given to a horizontal company. The common law route can provide the flexibility and adaptability that regulatory intervention often lacks; however, it will depend on litigants voicing concerns.

9.6 Conclusion

In many ways, horizontal directors epitomise the push and pull of our corporate governance system. Directors are expected to monitor management, to provide expertise and networking, and to make the corporation’s most important decisions.Footnote 81 Yet, we lean on outsiders to serve as directors, and we allow, and even encourage, their service on other boards, potentially undermining their ability to appropriately serve their director role. Indeed, many directors serve on more than one board when given the opportunity. Director is a desired position due to the relatively limited time commitment to each board, significant salary and perks, and limited exposure to legal risk.Footnote 82 Additionally, serving on several boards across industries, within the same industry, and even within the same SIC code can benefit not only the director but also the companies she serves – at least under certain conditions.Footnote 83

Yet, there is an open question as to how horizontal directors should fit within our current antitrust regulatory framework and corporate governance regime. Moreover, how to appropriately balance the competing interests remains unresolved. Similarly, it remains unclear how we should view horizontal directorships given increased industry concentration and vivid discourse regarding horizontal mergers and horizontal shareholdings.

This Article demonstrates that horizontal directors remain a prevalent feature (and bug) of the US corporate landscape. Future research into horizontal directorships is still needed, given the increased reliance on the board as an institution,Footnote 84 and the emergence of contemporary antitrust discourse regarding horizontal ties between companies through common shareholders. Understanding that not all companies are created equal, investors may be better situated than regulators to account for the rise in horizontal directorships and offer market-based solutions to the inherent tension that these directors present.