Relationships are not all the same. Some are linked to daily life, others are brought into play at more exceptional times; some are important, others are insignificant or occasional. After the initial encounter, the links between the individuals concerned acquire their own “content,” their “common motivation.” The subject of this section is the various sorts of relationships and their modes of existence. The differences observed between relationships are very closely linked to the questions asked in surveys. After all, network analysts generally begin by constructing lists of relationships on the basis of “name generators.” For example, questions such as “Who are your best friends?” or “Who did you speak to last week?” produce a list of names or first names. Some generators are intended to capture as many names of individuals linked to the interviewee as possible, while others are aimed at closer, more intense relationships.

Relationships always come with stories attached to them. But how do these stories arise? What is important? Some one-off interactions are memorable and leave a strong impression, but they do not constitute a relationship. An exchange of a few sentences, a certain affinity, or maybe a joke remain in the memory, but no lasting link has been forged. The difference between a relationship and an interaction is that an interaction is a one-off event, whereas a relationship is a series of interactions between the same individuals. If these interactions are repeated and become incorporated into certain routines, they may give rise to familiarity, mutual recognition, and expectations. In many cases, however, this series of interactions remains defined by the role more than by an attachment between individuals. Thus, one can go regularly to the same shop or club without a relationship ever developing, because each time this happens it is as if it were for the first time. The shopkeeper remains a shopkeeper, the customer a customer. Sometimes, by dint of repetition, but especially when an event or an encounter in another context causes those involved to step out of their roles, the new shared experience has the effect of changing the interactions that follow. A new layer of potential exchanges is opened up, the relational space expands and a story begins to take shape and unfold. This process can be spread out over time or may sometimes be very short if precipitated by an event or crisis.Footnote 1

Characterizing Relationships

Once the relationship is firmly established, various types of interactions will help to sustain it and keep it going. People talk to each other, face to face or on the telephone, they play tennis, they do each other favors, invite each other to dinner, and so on. Measurement of these interactions, of their frequency and variety, is useful in characterizing the relationship. Nevertheless, it is important always to separate these measurements, which relate to interactions, from those concerning the intensity of the relationship. After all, one can have very significant or affective relationships with people whom one sees just once a year or, conversely, have relationships that are neither intense nor personal with people one sees every day. Similarly, an exchange of small services does not automatically signify great commitment or a highly personal relationship. Thus, we will take care to distinguish between the “formal” dimension of interactions, their frequency and the exchanges to which they give rise, on the one hand, and, on the other, the substantive dimension of the relationships that they bring into play, while at the same time examining the linkages between the two aspects. For example, certain experiences or exchanges may alter the quality of a relationship. Thus, some people state that the transition from mere “chumminess” to real friendship dates from a vacation taken together or from crucial help given at a critical time. This being so, these same individuals will know other people with whom such exchanges have not taken place but whom they nevertheless describe as friends. Consequently, it is through questioning that the links between interactions and the qualities of relationships have to be investigated.

The knowledge each has of the other and of past interactions may not be symmetrical. One may know the other better than he/she knows him/her, whether because the other opens up more easily, because one is more “interested” in the other and more readily remembers what he/she learns about him/her, or because one has the advantage of outside information about the other. However, it is clear that a unilateral acquaintance cannot be considered a relationship. We may feel we have intimate knowledge of certain individuals with a high media profile (celebrities, politicians, etc.), but if we have not interacted with them, they do not know us and we do not have a relationship with them. If we have interacted (by getting them to give us their autograph, for example) but the person in question does not recognize us, there is no relationship either. The word “recognition” has several meanings, all of which may be involved in the construction of a relationship. A person recognizes our face and identifies us. A person recognizes our value and accords us a place in her world. A person is grateful to us in recognition of the help we have given her. The first case is essential if mere interaction is to develop further into a relationship, the second is closely associated with it, and the third may very well never happen even in some very important relationships. Thus, in order to become a relationship, knowledge of another person must be accompanied by interactions that will show, in particular, that we recognize that person as someone with whom we can associate. Thus, to recognize a person is to show a commitment to that person, with the minimum requirement being simply to admit the existence of a relationship, which is itself maintained over time. Thus, a word expressing commitment will represent a step toward other exchanges that, as they accumulate, will create the depth and the history that turns the interaction into a relationship.

Hence, a relationship implies mutual history, knowledge, and commitment. Here also, two meanings of the term are combined. Commitment is a sort of promise, an indication that the relationship is going to continue to be of interest to us in the future, that the recognition of another person will be maintained. By projecting this relationship into the future, it is being given a temporal dimension. The story has begun. Commitment is also a way of affirming that one is personally involved, willing to give “of one’s self” and ready to accept one’s responsibilities. In recognizing and affirming a relationship with another person, it is an individual’s identity that is being involved.

This commitment to another person is usually accompanied by an affective or emotional dimension. We value – to varying degrees – the people with whom we have relationships, we seek out their presence, we look forward to seeing them; for some of them, we may have feelings of friendship or even love. One may also, for various reasons, have relationships with people whom one does not value. Such enforced relationships may be linked to one’s family (the relationship between a woman and her mother-in-law can be very strained, but it is still a relationship, the product essentially of their roles within the family), one’s work (we try to remain polite with those colleagues whom we find disagreeable but have to deal with nevertheless), one’s neighborhood, etc. These enforced relationships are interpersonal relationships insofar as they involve repeated interactions, mutual knowledge, and a form of commitment, however minimal or formal. All things considered, however, interpersonal relationships have a positive affective dimension. Sociologists have tended to ignore this dimension, doubtless intimidated by its proximity to questions that tend to be the province of psychologists, the difficulty of dealing with these very subjective data that are difficult to gather and measure, or even by the lack of academic credit accorded to these questions in the dominant approaches to their discipline.

It would seem safer to infer the strength of a relationship from more “objective” or at least more factual information (in both cases, of course, any judgments are based on the statements of those concerned), such as the frequency of meetings or the possibility for mutual assistance. However, as we have already noted, such an inference is unwarranted and deprives us of the value of investigating the linkage between the practical and affective aspects of a relationship. It is, after all, perfectly possible to examine affects from a sociological perspective without entering into complex considerations. For example, asking two young women if they feel close to each other, if they are real friends or just buddies, or even what the nature of the tie between them is, may be sufficient to draw conclusions about the quality of the tie and its affective character without reducing them to any particular type of exchange. Thus, it can be seen that this affective dimension is absolutely central to the existence of the relationship and even to the most effective aspects of its strength.Footnote 2

Asking questions about the “mainspring” of the tie between two individuals, about the motivating force that “makes it tick,” is a way of adding flesh to the bones of the relationship. This dimension is very seldom tackled head on. The mainspring of a relationship is what constitutes the attraction and commitment between two individuals, what keeps them together, over and above the various qualities of the relationship.Footnote 3 This mainspring, or motivating force, has its roots in part in the individuals’ backgrounds and qualities and in the interactions and ties between them. However, it cannot be reduced to these elements. One of the questions put to the Caen panel sums up this notion of mainspring: “Finally, what brings you together, is it mainly …?” (Table 1.1) There followed a list of twelve items from which interviewees could select a maximum of two responses.Footnote 4

Table 1.1 Frequency of responses selected over the four waves of the Caen panel survey

| What brings you together: | % |

|---|---|

| A family tie above all | 28 |

| Friends, buddies in common | 15 |

| Our children (only in waves 3 and 4) | 1 |

| One or more shared activities (including work or study) | 13 |

| You help each other | 3 |

| You can confide in each other | 7 |

| An emotional attachment primarily (friendship …) | 25 |

| The simple pleasure of being together | 19 |

These response items require some clarification:

– In some cases, a family tie constitutes the relationship’s sole motivating force: it is “only” a family tie, which on some occasions is mentioned almost as an automatic reflex (if an uncle is mentioned, it is sometimes awkward not to mention the aunt); in other cases, the family tie is accompanied by other relational mainsprings (emotional attachment, personal qualities, etc.). However, with this response the family role takes precedence and is the dominant force sustaining the relationship.

– Another relational mainspring has its roots in another shared part of the individual’s network, namely “buddies in common.” This response shows the multiplier effect produced by a network, which grows by creating new relationships from the existing ones.

– The fact that children (usually of the same age) can constitute the main motivating force in a relationship was not suggested until the third wave of the survey, the participants having previously been too young. In this case as well, the mainspring has its roots in other relationships that establish connections.

– The shared activities response also places the relationship into its context. Whether it be school, university, work, or leisure, the relationship has at its heart a shared activity.

– Mutual aid may be the initial motivating force behind a relationship, but the fact that it applies to only a small share of the relationships here suggests we should be wary of the “utilitarian” vision of relationships. The exchange and resource dimension dominates the relational content here.

– The possible sharing of confidences puts the emphasis on the degree of intimacy in the mutual exchanges. Here too, the relationship is above all a vector for support, provided in this case by listening to very private words and enabling self-disclosure.

– Emotional attachment comes in second, but in first place if family is excluded. Thus, the majority of relationships are a question of feelings, which may seem obvious but is worth emphasizing.

– The “simple pleasure of being together” also emphasizes the free gift and conviviality that relationships provide above all.

– The importance of a shared past shows the importance of a relationship’s history, which may still be shaping a current relationship.

– The friend’s qualities are sometimes mentioned as the main motivating force, in which case the relationship really does revolve around the interpersonal dimension.

– The “not much, nothing” item shows that some relationships are mentioned rather by convention. This applies particularly when they are mentioned in “bundles,” for example, within groups of buddies or families.

This brief look at the mainsprings of the relationships, as those involved see them, shows that the substance of relationships is very diverse. Examination of some of their qualities will help to characterize relationships more precisely.

Relationships may have their roots in a single context or in several contexts simultaneously. This multiplexity shows that a network can superpose different social circles and combine various contexts, even for the same relationship. But at what point can we say that a relationship is multiplex? When it moves out of the place where the individuals concerned first met? When the variety of topics discussed goes beyond the register of the initial context? When the contexts in which shared activities and exchanges take place proliferate? When motivating forces emerge that place greater emphasis on personal qualities? Obviously, there is no one answer to this question and some situations are ambiguous. Some contexts, such as work and neighborhood, are spaces in which relationships are fairly commonly located, giving rise to designations for the clearly identified relational roles of colleague and neighbor. However, contexts can be defined on the basis of many criteria other than these roles or the initial settings; these include places currently frequented, shared activities, and so on. It depends on the relationships under investigation.

Multiplexity is connected with the intensity of ties. In the Toulouse survey, multiplexity is measured by the number of contexts for which the same person is mentioned. Family members, friends, and close relationships are generally more multiplex than neighbors, colleagues, or mere acquaintances. In the Caen panel, this multiplexity is also measured by the number of contexts in which a relationship is mentioned, but also by the multiplicity of shared activities and by the interviewee’s declaration that he/she spends time with that person outside of the context. This last point is, incidentally, one of the two criteria used to differentiate strong from weak ties. For each of the names mentioned, interviewees were asked if they considered that person to be important or if they saw him/her outside of the context in question. This questioning was based on the hypothesis that a tie capable of freeing itself from the original context by becoming more multiplex is more particularized and personalized and thereby becomes stronger. If the relationship was declared important or moved outside of the context, it was regarded as a strong tie. Use of these two criteria enabled us to verify the hypothesis of a link between multiplexity and the strength of a tie: 82 percent of the relationships regarded as important are indeed multiplex ones. This said, the two criteria do not overlap completely since, despite everything, 18 percent of important ties are not multiplex (these tend to be family ties, although not exclusively so). Moreover, 36.6 percent of non-important ties are actually multiplex. Thus, the two notions of a tie’s strength, on the one hand, and its multiplexity, on the other, are not exactly one and the same thing. Certain specialized ties may acquire great intensity (a former professional partnership, for example) whereas more multiplex relationships may turn out to be lacking in intensity (e.g., relatively peripheral friends in a group of young people).

Efforts have always been made, to varying extents, to assess the strength of ties. Obviously, certain relationships involve considerable attention and affection, whereas others remain at a minimum level of recognition. Trust and emotional intensity were two of the criteria used by Granovetter to define the more general notion of the “strength of a tie.”Footnote 5 We will have an opportunity to reconsider this notion, which incorporates various aspects of relationships, but we can say here that everything we have just touched on can be highly variable in its intensity, whether we are dealing with the knowledge, commitment, emotional dimension, mainspring, or multiplexity associated with the tie in question. These variations in intensity are complex and utilize a mix of registers involving a number of different dimensions. Nevertheless, most network analysts have attempted to combine the criteria that seem to them most relevant in order to form two broad categories: “strong” ties and “weak” ties. The idea is to differentiate those relationships that constitute a “cluster” of close associates around the individual from those that form a wider “halo” around him, connecting him to the wider society. The problem is that it is difficult to compare surveys in this respect, since the criteria used are not the same and are sometimes even left very vague. It sometimes seems that the frequency of meetings or the level of mutual support provided are regarded as the primary criteria, while in other cases it is suggested that certain roles, notably those of family and friends, give the tie greater strength. In some surveys, the name generators immediately target the strongest ties, the most intense “core” of a network, by giving interviewees the choice of naming the people they consider “closest” to them.Footnote 6 Thus, once they have been identified more or less methodically, strong and weak ties constitute two levels of relationship that can be fruitfully compared.

One of the points our two surveys have in common is that they reconstruct a significantly wider network. Afterwards, the respondents were asked to describe the ties very precisely. In this method, the intensity of the tie is not confused with the forms of interactions and the link between these two dimensions can be posed in the form of a question, as we indicated above. Consequently, we preferred to begin by constructing the entire network on the basis of the contexts; we then identified the individuals the respondents regarded as important, asked them if they considered them to be close friends, buddies, or mere acquaintances, and had them specify the motivating force behind the ties, etc. We then examined how many times they saw them in a year, what activities they shared with them, if they had already helped them or influenced them in their decisions, if they would be willing to share a flat with them, etc.

Relationships in Networks and Circles

Let us now look beyond the characteristics of relationships considered as singular entities and examine the way in which they combine together to become part of networks and circles. The first question is that of the scale of an individual’s relational environment.

One of the ways of getting an idea of variations in intensity and of their consequences for our perception of relationships and the size of networks is to ask oneself the apparently simple question of how many people one knows. What does it mean to know a person? Where does a relationship begin? At what point does one stop being part of an interaction between strangers or playing a prescribed role? These are actually not simple questions. If the threshold were to be set at the lowest possible point, then coexistence of any kind would ultimately be regarded as a relationship and one could be linked to the planet’s six or seven billion other inhabitants. This, as it were, is the ground zero of relational intensity. One commonly used way of setting a minimum threshold is to require that each person knows the other’s name. However, studies have shown that there is an “anonymous swathe” of people whom one can locate in terms of where they live and what they do for a living but whose name one does not know.Footnote 7 For example, when elderly people are asked about people whom they could ask to help them should a problem arise, it is not uncommon for them to give answers such as “the little lady who lives on the corner of the street” or “the nurse who comes every other day, she’s so kind.” Conversely, there are some people whom we know by name but whom we do not regard as acquaintances. Nevertheless, memorizing someone’s name is a useful criterion for identifying ties, which may be very weak. How many people do we know in this sense? Various experiments have been carried out, for example, by encouraging people to remember names with the telephone book.Footnote 8 Obviously, the results depend on the method used, but they range between 600 and 6,000 names depending also on country, town, and the social status of the individuals questioned; it turns out that the number of people one knows or has known is around 5,000 on average. Thus, if we use knowing one another’s name as the criterion for defining an individual’s relational environment, then that world is very densely populated. However, many of these relationships obviously operate at a minimal level of commitment and knowledge. We would not dare to ask even a very simple favor of most of these people. So let us take another, more demanding criterion, namely the number of people we could ask to introduce us to someone we do not know. This is a favor that commits a person: to introduce someone is often also to act as guarantor, to vouch for his or her qualities. It is estimated that, in general, the number of people meeting this criterion is on the order of 200 on average.Footnote 9 The anthropologist and biologist Robin Dunbar put the size of “natural human groups” at no more than 150 individuals, due to cognitive constraints.Footnote 10

In many surveys of personal networks, such as that conducted by Fischer, name generators are used. Between 15 and 30 names are obtained on average by this method (18.5 in Fischer’s case, 27 for the Toulouse survey).Footnote 11 For the Caen panel, using a name generator based on all life contexts, the average number of relationships per respondent, and taking all waves of the survey together, is 37.6 (the people whom one knows or with whom one speaks in each of these contexts). The average number of strong ties (multiplex or important ones) is 23.4, while the average number of weak ties (neither multiplex nor declared to be important) is 14.2. Again, in this Caen panel survey, the interviews in each wave of the survey always opened with the following question: “Who are the people who are currently important to you, who matter to you?” On average, 10.4 names were mentioned in response to this point-blank question, which is similar to the name generators that target the core of networks of close relationships. And if the aim is to identify the more intense ties, then the name generators used in surveys of the type conducted by Fischer include some that target, for example, the people with whom the interviewee discusses personal problems or asks for advice when making important decisions. On average, such questions generate just two or three names. A result of the same order is obtained when the name generator focuses on interviewees’ confidants, the people to whom they are willing to entrust serious, secret things that can affect their lives. In these cases also, the number of ties falls to a handful, three on average.Footnote 12

The various criteria for measuring the intensity of ties usually tend to go along the same lines, but this is not always the case. When the individuals in question live far away from each other, the criteria for measuring intensity, such as intimacy or affective quality, are disconnected from those used to measure actual practices, such as the frequency of exchanges or the importance of any material support. The strongest ties, as measured by the intrinsic criteria of affective intensity, tend to be more frequent in geographically distant relationships than in those that are in the neighborhood. We will examine the spatial aspect of relationship networks in greater detail in Chapter 8, but we can state here and now what this difference signifies, which is that only “strong” ties as measured by the intrinsic criteria withstand distance. This also confirms that the various criteria usually used to assess the “strength of ties” must be differentiated from each other. By shifting the cursor of relationship intensity in this way, we have moved from several thousand to just a few names, around 1,000 times fewer. Thus, our idea of a person’s network differs considerably depending on the criteria we adopt to identify the relationships. The choice and construction of the types of name generators are absolutely crucial in network analyses and go hand in hand with very specific hypotheses and research objects.Footnote 13

The case of the family is a rather particular one. After all, the members of our family constitute a more or less clearly defined and finite unit that is governed by the rules of kinship. We cannot extend it simply on a whim, even though we might declare that a friend is “like a brother to us” or that certain family ties, such as those in reconstituted families, have certain similarities with the relationships between friends. Moreover, the relationship between a mother and her daughter is obviously not fully delineated by the social rules and prescriptions that define the mother-daughter role. The interactions between them may be harmonious or conflictive, close or strained. Some authors speak of the relative “liberalization” of family relationships: modernity is said to be turning family ties and obligations into primarily elective and affective relationships.Footnote 14 However, although kinship today undoubtedly forms the basis for a more diverse range of relationships than used to be accepted in the past, it is still a structural, anthropological tie that is not readily negotiable.

Above all, it is important to separate those aspects of family relationships that are a product of family roles from those produced by the development of a family relationship over time, that is, by its history. To that end, we can attempt to isolate these two dimensions from each other: the one that reflects the symbolic, anthropological, and structural roles of parents and their children or of brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, etc., and the one that reflects the temporary and evolving experience of kinship and of interactions with family members.Footnote 15 Family relationships develop on two different levels: that of family position, which remains unalterable and unconditional regardless of what happens, and that of the history of the relationship, which gives it a variable intensity and causes it to evolve and be sensitive to events. Relationships change at the various stages of the life course. In particular, when young people become adults, they construct a relationship with their parents that becomes increasingly interpersonal. The fixity of family position and the role it determines is gradually overlaid by an increasingly substantial relational dimension that is based more and more on interpersonal interactions and developments. This is not to say that the relationship replaces the formal role, rather that it envelops and coexists with it. This new relationship “between adults” is constructed both within the family role and with the addition of an increasing dyadic relational dimension. This is the story told, for example, by Emeline, one of the young people in the Caen panel who observed how her aunt Odile’s view of her changed. Initially, her aunt simply “pigeonholed” her as a child in the family:

For her, I was absolutely just a part of the family structure. I didn’t particularly stand out in my family. She used to bawl me out sometimes, because at that time she was still pigeonholing me as a teenager, along with her own sons. It’s completely different now. We have great conversations. So I like her a lot. And now I really stand out as an individual relative to my family.

This individualization develops in tandem with the adult relationship, not outside it but above and beyond it.

The ways of characterizing relationships listed above concern the relationship itself – its intensity, its diversity, and its qualities. However, it is also useful to characterize a relationship in terms of the attributes of the parties involved and, in particular, to compare these attributes in order to assess their degree of similarity. Such a characterization is located at the level of the dyad, which comprises the two individuals connected by the tie. In general, homophily is defined as the tendency to maintain relationships with individuals who are similar to oneself, at least on one level. Homophily or similarity may concern a large number of characteristics. A relationship may be homophilic in terms of age (i.e., there is little difference in age between the two individuals), gender (two men or two women), level of education (both parties are graduates), etc. The friends may be similar by one criterion but not according to another. This dimension of relationships is very important, since it provides a starting point for addressing the question of social cohesion and segregation processes. The effects of homophily are generally quite pronounced but they vary depending on context, social category, and type of relationship. The fact that people tend to keep company with others similar to themselves, including when it comes to “voluntary” relationships, is evidence of the strength of the social divisions in question, as well as of the unequal distribution of that strength in society.Footnote 16 Thus, the degree of segregation and self-regulation varies depending on the sector and constituent element in question. We will return to the question of homophily in Chapter 9. The important thing here is to be aware that a relationship is characterized by its own qualities but also by the distance between the characteristics of the individuals that it connects. On a larger scale, this preference for people like oneself sheds light on and reinforces social divisions and the various effects of segregation.

Nevertheless, homophily is far from being the rule and, fortunately, conflicting tendencies disrupt its unifying tendency. Thus, partners can be characterized not by their similarity or dissimilarity but by their complementarity. Many relationships are, after all, based at least initially on complementary roles: doctor-patient, teacher-pupil, and so on. This complementarity can be instituted or formalized, but it may also be more informal and based on subtle character traits or skills. Selectors for team sport are constantly searching for complementarities. This is a relatively unexplored aspect of social relationships but it may be very important in pairing or matching situations. Thus, each context is a combination of homophily and diversity, with social institutions and contexts helping to define selection processes and specific balances. Thus, the school system contributes to strict segregation by age but tends, conversely, to mix boys and girls. It also claims to mix social classes, as long as catchment areas are respected and residential segregation is not too strong. This example points to the social and political issues surrounding this question of homophily.

Except for certain particular roles, exchanges of services do not provide the main motivation for relationships. It may even seem offensive to mention the idea that they might be motivated by self-interest or that the exchanges of services should be evenly balanced. In most cases, as we saw with the Caen panel, a relationship exists for itself, particularly for the affective tie or just for “the simple pleasure of being together,” while mutual assistance is the motivation for the tie in only 3.7 percent of relationships. This puts it far behind all the other more “disinterested” motives. And yet, even though a relationship may not be based on or explained by exchanges of goods or services, this does not preclude many diverse forms of assistance from circulating within it, whether they be material (mutual assistance) or more symbolic (influence). Households help each other out, with neighbors and friends lending each other tools, looking after children, and watering house plants or gardens during holidays; households belonging to the same family also provide services for each other but, in addition, generally take care of people in difficulty and may possibly also lend each other money. More broadly, giving advice or sometimes even simply lending a sympathetic ear constitutes an exchange of resources that helps to reassure, comfort, and make people feel like others, approved and recognized. Thus, certain “significant others”Footnote 17 may shape our lives without us thinking to say that they “helped” us directly. Furthermore, from our point of view, the term “resources” has its “dark” side, since it can imply constraints. After all, relationships generally result in constraints on behavior by directly preventing us from doing certain things, creating obligations, requiring time and attention, dissuading us, and so on. We will return to these aspects of relationships in Chapter 10.

Interpersonal relations (and the networks that they constitute) are combined with affiliation to collective entities that we call sets, groups, or social circles as the case may be. We do not intend to enter here into a debate on collective entities in the social world. In what follows, we will be taking into consideration only those groups of which individuals are able to recognize themselves as members. We use the term “social circle” to denote these groups. The individuals belonging to a social circle are aware of being part of that circle and can recognize those who are also part of it and those who are not. This excludes lists of individuals drawn up without this being brought to their attention, for example, on some websites. Social circles have boundaries, however fluid and shifting they may be, an inside and an outside, forms of collective identification (the fact that members can say “we”) and a designation. Its members share certain resources that define the circle relative to what is external to it: being a member of a family, a group, an organization, or a nation is to have a certain number of duties toward the other members and a right to the resources shared within the circle. Some of these resources define the parameters for the exchanges between members, their rights and obligations, as well as the way in which they are supposed to exercise them. These are mediation resources. They are the formal or informal rules, the stories about the circle, which, woven together, form a sort of collective narrative, as well as the tangible coordination mechanisms (internal means of communication, for example). This definition is a very broad one. Circles can be very small (pairs of friends) or very large (a nation); they may be very loosely organized (a group of friends) or highly structured (a company); they may last a long time (a church) or be short-lived (the people involved in a protest movement, for example). Logically, there is no reason why a relationship, which is a dyad or pair of individuals who have a sustained relationship for a certain period of time, cannot be regarded as constituting a particular kind of circle. Nevertheless, there is a fundamental difference between a circle comprising two individuals and a circle consisting of any number of people. In the first case, if one of the individuals withdraws from the circle or disappears, then the circle disappears at the same time, whereas a circle with more members can survive perfectly well if one of its members leaves, even though the departure will change it.

Circles can be differentiated from each other by the way in which they are likely to influence the formation of relationships among their members. First of all, there are those circles in which membership is generally “inherited,” such as families, clans, nations, and neighborhoods. Then there are “utilitarian” circles that are based on pursuit of an objective outside the circle itself, for example, companies or associations that have a specific goal. In this case, it is the objective being pursued (production, game, etc.) that leads the individuals to become members of the circle. To this category will be assigned all cases in which individuals become aware of having a common interest and come together in order to defend or promote it. Finally, there are “identification” circles, whose objective is based on an idea (religions, philosophical circles, and groups of supporters or “fans” can all be put into this category). In this case, the objective of participation seems to be the participation itself. From this point of view, even regulars in a bar can constitute a social circle. This last distinction is interesting, since the cohesion between the members of a circle of the second type (utilitarian circle) is not the same as the cohesion that exists between the members of a circle of the third type (identification circle). A relationship that is linked primarily to the existence of an external objective, such as a relationship between colleagues, can be closely dependent on their company’s ups and downs. It will not necessarily survive if the company goes bankrupt or if one of the members leaves the company. On the other hand, a relationship based largely on participation for its own sake will more readily find an autonomous motive for its continued existence. There are of course intermediate cases, that is, circles that have an objective and that also inspire identification from their members. Cases in which individuals who were not in any way predestined to find themselves brought together but who share one or more experience and consequently learn things about each other will be assigned to a fourth type of circle. Participants on an organized trip, prisoners of war, hostages, spectators at a sporting event or opera, passengers on a long airplane flight, people living in a new residential development, etc. might be included in this category. They are brought together more or less by chance, but they have certain issues to deal with together (getting to tourist sites, surviving, sharing a festive atmosphere, etc.), they share experiences, observe each other, exchange views, and learn about each other. It is a context in which relationships can be forged and maintained even after the initial experience.

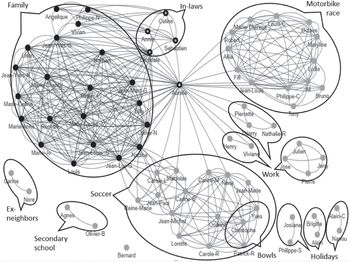

Let us give a more concrete example based on our data. Figure 1.1 depicts the members of the network that had developed around Joseph, one of the young people in the Caen panel, in the fourth wave of the survey. Joseph himself does not appear on it, since it is his network and he is by definition linked to all his friends. The lines represent the relationships between the people with whom Joseph keeps company. We have plotted the social circles in which these individuals participate with Joseph. Of course, some of these social circles extend beyond the people with whom Joseph spends time: many more people work in his company, for example, but the only people who appear here are those he knows in each of the different contexts. In some cases, the context has disappeared but Joseph maintains contact with some of the people he knew in those contexts, such as his ex-neighbors and people he met on holidays.

Fig. 1.1 The network of Joseph in the Caen panel (wave 4)

The first thing to note is the large family circle, supplemented by his partner’s family (in-laws). Aurélie, Joseph’s partner, occupies a rather particular position in that she is connected to almost all the circles except for the ones consisting of Joseph’s school friends, ex-neighbors, holiday acquaintances, and one of the three circles linked to Joseph’s work.

The family and neighbor circles belong to the first type of circle: Joseph did not choose them; they were given to him. The work-related circles are based on pursuit of an external objective. The soccer and bowls (petanque) circles (the latter game involves just some of his soccer buddies) also exist to fulfill an objective (playing sports or games), but the fact that they include friends who are not, strictly speaking, players (the girls, in particular) indicates that they also exist for purely social reasons. With those whom he calls his “soccer gang,” Joseph does not just play soccer but also maintains friendly relations for their own sake (the pleasure of meeting up, having dinner together, etc.). Thus, these circles combine the two types of motive. Finally, other circles are based on shared experiences, including vacations and the motorcycle endurance race, where Joseph has met friends. Thus, most of the relationships unfold within circles, at least for a time, and are characterized by the roles assigned in that context. The roles vary in significance, depending on the circle in question. In the family, they are strongly defined and the linkage between circle and relationship is very strong. In a company, they are moderately well defined while among a bunch of friends they may be implicit and more flexible, but in many cases, they do exist nevertheless. Relationships may remain very closely linked to these circles, but they can also become independent of them, disconnecting themselves more from the circle as they develop their own “rules of relevancy.”Footnote 18

Relationships constitute a relevant entity since they exist to some extent beyond circles. Even a highly specialized relationship, defined by a particular circle, can become an interpersonal relationship when the protagonists begin to move away from the roles assigned to them by their position in the circle and to add other interactions to them and become partially non-substitutable for each other. From one point of view, a relationship constitutes a departure from a role. As it develops, a relation comes in tension with the circle or circles in which it was originally located and finds its own dynamic, one that is separate from the circle’s. In order to explain this tension, we can use the notions of embeddedness and decoupling. Drawing on the work of Harrison White,Footnote 19 albeit with a few modifications,Footnote 20 we will use the term “embeddedness” to denote the dependence of one social formation (in this case an interpersonal relationship) on another (in this case a circle) and “decoupling” to denote the reciprocal dynamic tending toward autonomy. By extension, we will use the same terms to denote the processes leading to increased dependency and autonomy. A relation becomes autonomous when it becomes uncoupled from the circles in which it first developed, that is when it is no longer reducible to them.

Forms of Regulation

Everyone is accustomed to having exchanges with people in various contexts that seem to arise “naturally.” If somebody stops a person in the street in order to ask his way, he is going to obey certain rules of politeness that mean the person will not run away but will agree to listen to him. If somebody makes inquiries of a shopkeeper or craftsperson, here too there will be a sort of trust arising from the fact that this person is well established, which in turn means that the potential customer quite naturally expects a good quality of service and that the tradesperson knows he will be fairly remunerated for his work. If somebody is a member of a sports club, the other members will expect him to behave in accordance with the club rules. Finally, with his partner, his family, and his friends, mutual knowledge has been acquired and over time habits have become established that enable them to understand each other without having to spell things out, thereby facilitating exchanges. All this seems so self-evident that one is no longer aware that these are in fact forms of relationship regulation, whether they be universal, instituted, or acquired over the course of time within a restricted circle. If these forms of regulation did not exist, all interactions would require prior negotiation of the conditions under which they were to proceed. To borrow the terminology used by economists, this would give rise to considerable transaction costs. This is why all societies have developed and institutionalized relational roles and conventions that are universally recognized and ensure that interactions are always accompanied by a certain degree of trust, without which it would be necessary to renegotiate the conditions of each exchange afresh.

The notion of trust is a very complex one and may give rise to typologies of varying degrees of sophistication. Some authors, for example, make a distinction between voluntary trust (which results from a reflexive choice, a calculation) and assured trust (which is taken for granted in a given context),Footnote 21 or even the trust that results from an institution or a contract, from collective pressure, or from experience of another person’s reliability. This trust is constructed over time and evolves in the course of learning processes and reconstitutions that make it a dynamic process. For Georg Simmel,Footnote 22 trust is midway between knowledge and ignorance of a person. While it is true that trust leads to a reduction in uncertainty about other people, it is not limited to experience, since it also makes it possible to anticipate what will happen, thereby making experience unnecessary. After all, the trust one grants extends commitment beyond mere extrapolation from experience by attenuating uncertainties about others.

Thus, trust is based on a variety of factors; some are highly institutional, collective, and structural, others more dyadic, constructed out of the history of the interactions between the two parties. Our first type includes everything relating to the knowledge shared by all members of an entire society, such as language, the rules of politeness, customs, etc. They are generally acquired through socialization and prove to be fairly stable and shared, so that individuals can “count on them.” This same type also includes all the material and legal arrangements that contribute to the organization of life in society and provide support for people in their daily lives. If a person starts to behave aggressively, one can remind him of the rules of politeness and also threaten to take him to court. Similarly, doctor-patient relations are not based solely on social roles but are also shaped by legislation (with which doctors must comply) and various mechanisms, procedures, and arrangements (the doctor’s office and its instruments, the medical association, internet health forums, etc.). Here, the institutional arrangements serve to mediate trust. We also include in this type instituted social roles, which, in the interactions that bring them into play, constitute a way of creating the trust that makes a specific interaction possible. Adoption of a role (shopkeeper, doctor, teacher, expert) defines the conditions under which an interaction takes place. Kinship is also governed by rules and a more or less implicit hierarchy. At the same time, a role to some extent fixes the conditions under which an interaction takes place and inhibits the development of forms of exchange other than those prescribed by the role. It is difficult, for example, for a pupil to become friends with a teacher or a patient with a doctor. Here, trust is linked to the legitimacy and complementarity of the roles. We also assign to this category the trust established through participation in a circle in which the rules and customs of the larger circles of which it is a part are recognized but where habits and rules specific to the smaller circle may also develop. This can be easily illustrated by observing, for example, how a religious circle, a family, or even a group of young people functions. These “cradles of trust” are based on shared membership in circles of varying size and type, of which they constitute the concrete, palpable part that is “within arm’s reach.”

A second type of trust arises more directly from the effects of the network itself. For example, a person might trust someone because he or she is a close relation of somebody they trust or on whom they can exert pressure. Here, trust is linked to the structural effects of interrelationships.

The third type is based on knowledge acquired through similarities or shared experiences that are not confined to role performance. This is more intimate, “dyadic” knowledge that is difficult to transmit. If the other person seems to be one of our own kind or if we have personally experienced their qualities, then we bestow on them a trust that is associated only with the two of us, with what we have both accumulated over time. It is often this kind of knowledge that is emphasized when we talk of relationships, but it would be harmful to neglect the other kinds.

These types are not exclusive but exist in a state of tension with each other. On the face of it, all relationships draw to varying degrees on these different forms of trust. The trust between parents and children, for example, is rooted both in references to established roles and in shared experiences. Conversely, even in the case of a very loving couple, their relationship cannot be reduced to love alone, since it is impossible to ignore the fact that, in most cases, one of the two partners belongs to the woman’s circle and the other to the man’s circle and that the roles associated with these circles will necessarily “catch up” with them at some point.Footnote 23 Romantic relationships are also shaped by all the collective references to romantic love that have accumulated since the nineteenth century. The same applies to friendship.Footnote 24 Thus, even in an interpersonal relationship, trust cannot be reduced to its strictly dyadic dimension but is generally also influenced by institutional, structural, and cultural factors. Even a relationship such as friendship is at least to some extent “embedded” in social expectations, in links with other relationships in the network, in cultural representations of what friends owe each other, and so on.Footnote 25

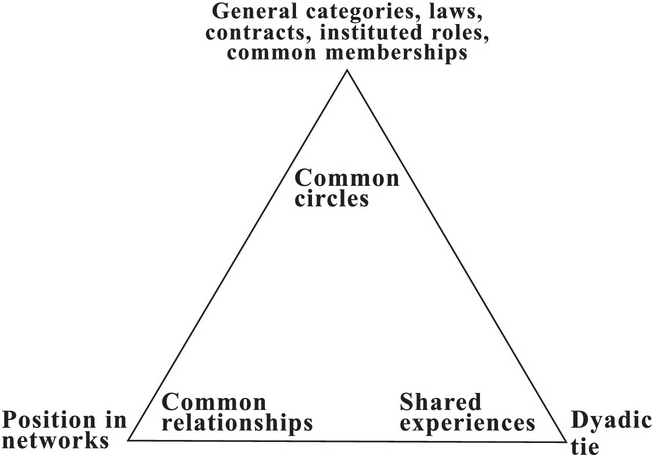

Thus, all relationships are shaped to some degree by points of reference that are more or less general and fixed and which subject them to the influence of systems of regulation. Even if we are inclined to believe that a relationship is absolutely unique, it is not totally improvised or wholly devoid of context or reference points. Even in the case of friendly relationships in which the two parties concerned are not accountable to anyone (unlike a romantic relationship, which very quickly comes up against the social frame of reference), their limits, conditions, and expectations are defined by (usually implicit) “rules of relevance.”Footnote 26 Thus, different types of relationships come within the orbits of different systems of regulation. We will adopt, with a few minor modifications, the typology of forms of relationship regulation developed by Alexis Ferrand.Footnote 27 In Figure 1.2, each vertex of the triangle acts as a hub representing one of the systems of relationship regulation. The closer the relationship is to one of the vertices, the more important this type of regulation is.

Fig. 1.2 The triangle of relational regulations

Membership of circles common to both partners in the relationship (top vertex) means it is possible to rely on categories, laws, or regulations and established roles that are specific to these circles, which may be very wide (institutions, a nation, a linguistic or cultural area, etc.) or much narrower (an association or the nuclear family, for example). Roles and formal rules, together with all the mechanisms, procedures, and arrangements associated with them, more or less determine the nature of the interaction, depending on each case. Sometimes legislation even dictates certain aspects of it. For certain roles, some of the interactions are fairly strictly determined by collective procedures and arrangements (parent-child, doctor-patient, etc.). For others, the rules or norms are simply a resource or constraint, a kind of support for the relationship (sports partner, leisure club, internet forum, etc.). The relational roles encompass those elements of the interactions determined by these established regulations. In the parent-child relationship, for example, the relational role defines the assistance one owes the other, but the interactions and content of the relationship generally go well beyond that. The resources associated with relational roles can be drawn on in various coordination processes. If the term “mediation” is used to denote all the processes during which individuals “accommodate themselves” to others, then the term “mediation resources” can be used to denote everything that makes circles a tangible presence in everyday life.Footnote 28 The first major type of trust described above equates to this type of regulation.

An individual’s position in social networks (left-hand vertex) gives rise to specific constraints and resources associated with the shared relationships (members of one’s partner’s family whom one is obliged to see because they are part of one’s partner’s close relationships, for example) or, more broadly, with the overall structure of these networks (an intermediary through whom one can get in touch with people who are important to us). This equates to the second type of trust.

Finally, situated at the right-hand vertex is what is specific to the two parties involved in the relationship and their shared history, what might be called the strictly dyadic dimension of the tie. To take up once again the notion of mediation resources, we might say that these are “dyadic” resources, that is, they are of value only to the two people in the relationship. This is the basis for the third type of trust described above.

It is true that if a relationship is made up of exchanges whose modalities are dictated entirely by common membership of a religion, for example (the parties meet at services and in prayer groups, but the communication stops there) or a company (they work in the same department and the exchanges are confined to work-related matters), then the history of the relationship will be of little relevance. Similarly, if a relationship between a shopkeeper and a client or between a doctor and patient has no object other than the professional relationship, then the relationship will not develop very far and its history will be of little interest for a study such as ours. However, not all relationships are “pure,” in the sense of being assigned to one or other of these types. Many relationships are shaped by a role and a history, or by a history and a contractual framework. Moreover, a relationship will develop according to this pattern: If each of the different interactions that constitute a relationship were to be represented by a point in the triangle, then they would form a trajectory that would move nearer to one or other of the vertices of the triangle at varying stages of the relationships. A relationship between two colleagues, for example, will begin near the top vertex, since the exchanges will be dictated by the requirements of their work. Gradually, their shared experiences will accumulate and their knowledge about each other will become more important than the professional environment in establishing the trust that links them. After a certain time, they may become true friends and the fact that they work together will become one opportunity for exchanges alongside many others. In this case, the relationship will move toward the right-hand vertex of the triangle. However, it is also possible that, after a period during which friendly relations developed, they will fall out over work-related issues or find themselves competing with each other for promotion and consequently revert to purely professional exchanges and stop seeing each other outside of work. Nevertheless, they can remain an important part of each other’s professional network.

*

* *

Thus, relationships are forged in contexts that influence their history, qualities, intensity, motivations, and the similarities between the partners. Sooner or later, however, they may start to exist independently of these original contexts, moving away from the social role and drawing closer to the network-regulated hub or to the one more focused on interpersonal relationships.

If we try to synthetize now what constitute relationships, one may imagine a meeting in the street: two friends (let’s call them James and Luke) are out for a walk together, and they run into another person (let’s call him Mark). James knows Mark, and he tries to explain his relationship to Luke after a while. We imagine this dialogue:

Luke: “Who was that?”

James: “He’s a buddy of mine … a good guy. He’s doing a computer course. I met him on a course a few years ago. And then I lost touch with him when I left Paris. When I came back, I met up with him again at the golf club. My wife also helped his daughter, who was having problems with math. We mainly see each other for a game of golf, but sometimes we invite them over to our place. I also call him when I’m having problems with my computer.”

This very commonplace little dialogue already contains many of the aspects of social relations that were examined in this chapter. Firstly, their attitudes and words differ from the generic codes on which people rely when interacting with someone they do not know. For example, they call each other by their first names (which they therefore knew already) and their exchanges revolve around a plan to “meet up” that they both seem to take for granted. James then fills in the backstory by giving details of the times and situations he has shared with Mark. A relationship always has a story attached to it. James and Mark got to know each other through an institutional framework, namely the circle formed by the course they were attending, where the interactions between them were regulated by the complementarity of their roles (trainer-learner in computing). When this contextual framework disappeared at the end of the course, their relationship came to an end. They might never have seen each other again, even though James says they had hit it off. Moreover, this is what must have happened with most of the other course participants. It was pure chance that James returned to Paris and that they met again at the same golf club. Chance is important. Here it brought James and Mark together before they had to take the initiative and make other arrangements to meet up.

However, let us suppose that Mark, or James, has a back problem and can no longer play golf. Will they continue to see each other? In other words, has their relationship become sufficiently independent of the circumstances that have so far kept it up to date so that it remains alive and is more than just a relationship based on memory? If golf no longer provides the main opportunities for them to meet up, perhaps mutual assistance, whether with gardening or computer problems, will take over. Or maybe the mere pleasure of being together will be enough to inspire them to meet up. Clearly a relationship is caught up in the interplay between the contexts in which it is constantly being renewed and on which it depends. It is not until it begins to exist independently of those contexts and is able to survive outside of them that it becomes primarily an interpersonal attachment.

However, they met again in a different shared context, the golf club, which is a more flexible circle in which they play on equal terms and their relationship is based more on similarity than complementarity. Their knowledge of each other and the recognition they accord each other were changed as a result. The relationship became more multiplex. A network effect came into play when James’s wife started to help Mark’s daughter with her math. As a result, the relationship was now positioned more toward the relational vertex of the triangle. The commitment started to be shared and it was two families that were now associated. Invitations to each other’s home are an indication of this development. However, the dyadic dimension also becomes apparent in James’s affective description of the relationship, when he declares to Luke that Mark is now “a very good buddy.” Thus, we are illustrating here the stages through which a relationship emerges and becomes established. By going beyond the interactions strictly prescribed by the individuals’ roles, leaving the initial context of the meeting, accumulating experiences and forging a history, increasing their knowledge of each other, and constructing a form of trust that goes beyond this knowledge and reduces uncertainty, a relationship becomes decoupled from its various contexts. Its qualities (intensity, multiplexity, homogeneity, functionality, etc.) will be intrinsically linked to these processes and this is why we place relational dynamics at the heart of this book.