Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

3 - Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Summary

‘When you durst do it, then you were a man’

(Lady Macbeth to her husband. Shakespeare Macbeth 1.7 49)‘Manhood is only important if you care.’

(Gilmore 1990: 217)Chewing the mask

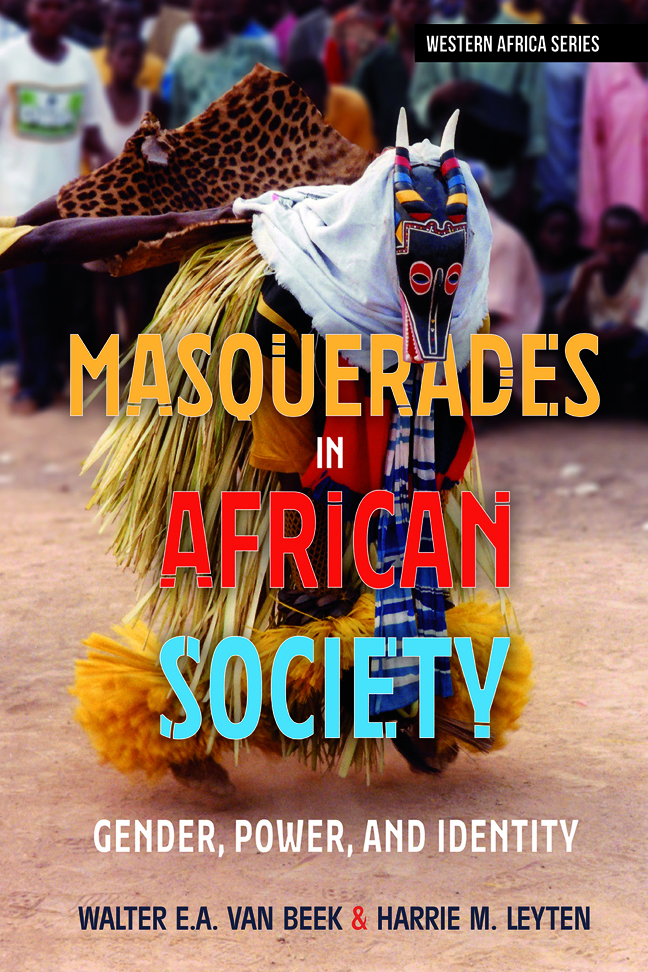

The rains have passed and the harvest is ripening in the fields. A group of young boys, aged ten to fifteen years, sit down on the ground somewhere in a wooded spot around a Bobo village in the west of Burkina Faso. The youngsters are not alone, for older boys with scowling faces and a threatening demeanour surround them, instructing the smaller ones on what they should do. The older boys form the age-set just senior to the youngsters, who in fact are in the process of forming the new set. What the young boys are doing is highly significant: they cut branches from a tree species considered sacred throughout the region, and put together a mask costume made solely out of those leaves: the sahasahala (the quick one). The boys are excited, as they have finally come out in the open, here in the bush where everything is going to happen. This is the year when they should start their long initiatory trajectory, and they welcome it. In order to arrive here, they had to ask for the rituals themselves in a propitiation to the elders that forms part of the ceremony. No less than three times they had to submit a formal, ritual demand for initiation, through the intermediary services of the smith. Reluctantly, consent was finally granted after gifts of beer and chicken, and yesterday night the initiation had begun. In the pitch-dark they had been taken from their homes and placed inside a dark room, naked, cold, and frightened, surrounded by – judging from the sounds that came from the outside – a battle raging between people and beings uttering high-pitched cries. Food was offered to them, but it was food suited for an orphan's funeral. Their only contact with the outside was through a few smiths who came into their hut – nobody else; it had been a long, hungry, and scary night.

This morning they had awakened with the loud, shrill cries of a mask posted right at their door.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Masquerades in African SocietyGender, Power and Identity, pp. 79 - 118Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023