3 - The most cherished objects in the home

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

Summary

Empirical events gain meaning only when they are interpreted through a conceptual framework. This is why in the preceding chapters we have outlined a theoretical perspective from which to view transactions between people and things. It is also true, however, that theories are directed and corrected – in fact, cultivated – by systematic exposure to facts. Therefore in the next four chapters we shall alternate development of the theory with presentation of the findings of an empirical study, highlighting first one, then the other aspect of the investigation. What follows, therefore, is neither a purely theoretical analysis nor the outline of a factual report; instead, it is a combination of both – an exploratory effort – in which insights are gleaned from data and new empirical analyses are presented to bolster emerging hypotheses. Hence, the conclusions will often remain heuristic rather than definitive. On the other hand, the flexibility of such a method will provide us with a greater variety of leads than could a more conventional one.

To find out what the empirical relationships between people and things in contemporary urban America are, in 1977 we interviewed members of 82 families living in the Chicago Metropolitan Area. Twenty of these families lived in Rogers Park, a relatively stable community at the northern limits of the city of Chicago; the remaining were selected from the adjacent suburb of Evanston, an old and diversified city in its own right, even though it is geographically indistinguishable from Chicago.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

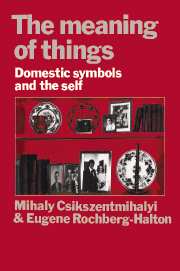

- The Meaning of ThingsDomestic Symbols and the Self, pp. 55 - 89Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1981

- 5

- Cited by