Book contents

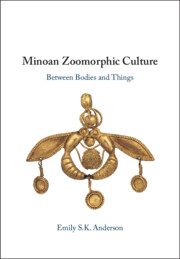

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- One Life among the Animalian in Bronze Age Crete and the Southern Aegean

- Two Craftiness and Productivity in Bodily Things

- Three Stone Poets

- Four Likeness and Integration among Extraordinary Creatures

- Five Singular, Seriated, Similar

- Six Moving toward Life

- Concluding Thoughts

- References

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 May 2024

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- One Life among the Animalian in Bronze Age Crete and the Southern Aegean

- Two Craftiness and Productivity in Bodily Things

- Three Stone Poets

- Four Likeness and Integration among Extraordinary Creatures

- Five Singular, Seriated, Similar

- Six Moving toward Life

- Concluding Thoughts

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Minoan Zoomorphic CultureBetween Bodies and Things, pp. 380 - 407Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024