Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- 1 Spatiality and Subjectivity in Xie Jin's Film Melodrama of the New Period

- 2 Society and Subjectivity

- 3 Huang Jianxin and the Notion of Postsocialism

- 4 Neither One Thing nor Another

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

3 - Huang Jianxin and the Notion of Postsocialism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Romanization of Chinese

- Introduction

- I FILM IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC

- 1 Spatiality and Subjectivity in Xie Jin's Film Melodrama of the New Period

- 2 Society and Subjectivity

- 3 Huang Jianxin and the Notion of Postsocialism

- 4 Neither One Thing nor Another

- II FILM IN TAIWAN AND HONG KONG

- Chronologies

- Glossary

- Scholarly Works on Chinese Filmmaking in the 1980s

- Index

Summary

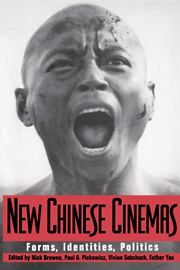

It is easy merely to assert that Huang Jianxin was perhaps the most politically daring young director to appear in China in the troubled 1980s. The difficulty in assessing his work arises when one tries to locate Huang's highly innovative trilogy of films, The Black Cannon Incident [Heipao shijian, 1986], Dislocation [Cuowei, 1987; also known as The Stand-in], and Transmigration [Lunhui, 1989; also known as Samsara], in any conventional conceptual framework. In a general sense, Huang's work belongs to the vaguely defined category of Fifth Generation films made between 1983 and 1989. However, he was really the only important director in the elite group consisting of Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Zhang Yimou, Wu Ziniu, and a few others who dealt exclusively and explicitly with the profound problems of the contemporary socialist city. One hardly needs to be reminded that it was precisely in this sector of Chinese society that the massive popular protests of the spring and summer of 1989 originated. Thus, more than the works of any other Chinese filmmaker, Huang Jianxin's anticipated that extraordinary turmoil.

In December 1988, a time of considerable cultural openness in socialist China, I attended a prerelease screening of a rough cut of Transmigration at the Film Archive of China. This screening was attended primarily by film specialists and critics in Beijing such as Li Tuo and Zheng Dongtian, who were eager to get their first look at a work that was rumored to be highly controversial.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- New Chinese CinemasForms, Identities, Politics, pp. 57 - 87Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994

- 26

- Cited by