The international peacebuilding endeavor is framed as the attempt to create sustainable peace in post-conflict countries by transforming the root sources of conflict in these societies. The crucial first stage is to bring together the leaders of warring factions in constructing a peace settlement by which all sides agree to abide. A peace settlement can be reached in a number of different ways, as illustrated by the case studies in this book: as a result of a stalemated conflict as in Cambodia; attained as part of the journey toward independence as in East Timor; or forged through a decisive externally assisted military victory as in Afghanistan. No matter how it is reached, however, the contours of the peace deal are the manifestation of the terms on which parties previously locked in conflict are willing, at a particular moment in time, to attempt to coexist with each other. The peace settlement is, in effect, an externally imposed critical juncture that sets in motion the peacebuilding pathway that follows. In addition, an elite peace pact offers a snapshot of the domestic power balance emerging out of conflict and a strong indication of the goals and motivations of the parties to it, providing essential clues into the political realities of the peacebuilding challenge. Like other critical junctures, the peace settlement phase represents a moment of highly contingent politics, where the choices made by political actors have lasting repercussions.

Internationally mediated peace settlements in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan attempted to resolve the problems that created conflict at the outset – and served, in turn, as the basic agreements upon which the subsequent peacebuilding interventions were predicated and implemented. Each country narrative presented in this chapter analytically explores the causes and nature of the conflict period and illustrates how the peace settlement was achieved. The historical overviews emphasize those structural elements of each country's political trajectory that had lasting effects on the domestic elite power balance and political culture. In particular, they focus on the ways in which elites use the infrastructure and resources of the state in their power struggles and in building neopatrimonial networks of political support – in attempting, in short, to establish political order. In the previous chapter, I made the case that a peace agreement is, in practice, a conditional elite pact that is best understood not as a rational deal that strikes a stable compromise between elite factions but rather as the concrete representation of the legacies of the pre-conflict political trajectory and the particular power balance that emerges from the conflict. The empirical evidence presented in this chapter illustrates how the extraordinarily fluid politics of the settlement phase, against the structural backdrop of the preceding political trajectory, initiate a new phase of regularized elite conflict over the construction of political order.

For each country, I begin with a brief historical background, paying particular attention to the basic challenges of governance and political order – focusing especially on the political–economic objectives of different elite factions and the rivalries among them as well as the overall institutional infrastructure and capacity of the state. I then turn to a discussion of the conflict, emphasizing the composition of the warring factions, the contours of their grievances and the nature of their claims to state authority. In outlining the nature of political group competition in each of the cases I build on Michael Doyle's insightful notion of “ecologies of transitional politics” to characterize the nature, coherence, and orientation of the different factions to conflict and settlement.Footnote 1 The political–economic characteristics of the factions must be understood in a dynamic sense, since they change over time, and they are crucial for explaining the subsequent interaction between international peacebuilders and domestic elites during the transitional governance phase. The coherent Cambodian factions may have originally been resigned to the peace process but, over time, they became increasingly hostile to it and to each other. The umbrella national resistance movement in East Timor, seen as the natural broad-based counterpart to the United Nations, fractured quite quickly after independence. In Afghanistan there were a handful of relatively coherent factions that have, since the country's liberation from the Taliban, proliferated into many smaller groups with particularist claims. The narratives in this chapter attempt to capture the dynamics of fluid elite factional interests that are, in turn, central to understanding how post-conflict political order is constructed.

The Cambodian Civil War

Modern Cambodian political history combines the legacy of an ancient indigenous empire, the effects of colonization, independence, and Cold War external influences, and the agonies of civil conflict and the genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge. The combination of these factors contributed to the length and severity of the civil war, as well as to the difficulty of the political settlement to the conflict. In turn, the legacy of weak state capacity and compromised political legitimacy have deepened the challenge of constructing post-conflict political order.

The ancient Khmer empire, immortalized in the temples of its capital city Angkor, controlled a large part of what now constitutes modern Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries CE. With the decline of the Angkor empire, Cambodia became vulnerable to periodic invasion and occupation by these neighbors. The wars fought between Thailand and Vietnam on Cambodian soil in the 1830s and 1840s severely weakened the small kingdom's fragile institutions and carved up its territory. Cambodia's place on the map was saved when France imposed a protectorate upon the country and its obsolescent monarchy in 1863. As in their other colonies, the French prevented the development of a cohesive political or bureaucratic elite in Cambodia. Instead, they brought into the country a super-class of Vietnamese civil servants, merchants, and farmers who, along with a small overseas Chinese population, came to dominate the administrative and commercial realms in Cambodia.Footnote 2 The French constructed some degree of infrastructure in the country, but the Cambodian economy remained largely based on subsistence agriculture and traditional extractive practices in commodities such as rubber and other agricultural products.

The colonial French authorities designated the 19-year-old Prince Norodom Sihanouk king in 1941, marking a landmark event in contemporary Cambodian political history. Originally installed on the throne as a colonial puppet, Sihanouk proved over the following seven decades to be a shrewd political operator and remained one of the dominant figures of Cambodian political life until his death in 2012.Footnote 3 He played a central role in winning Cambodian independence in 1954, having decided at an early stage that his political survival hinged on his ability to emerge as a champion of Khmer nationalism against French rule. In 1955, Sihanouk abdicated the throne in favor of his father to become eligible to participate in national politics. In the election that followed his party won every seat in the national assembly. His party remained dominant for the next 15 years and he governed with no intermediaries between himself and his people, claiming legitimacy on the basis of his semi-divine connection with the peasantry. Like the French, he prevented the development of an independent political class in Phnom Penh, and continued the tradition of personalized political authority practiced by Cambodian rulers before him.

From 1970 onward, Cambodia underwent two decades of extreme political instability and a brutal civil war that included a tragic genocide. That year Sihanouk was overthrown and his regime was replaced by a right-wing civilian–military alliance supported by the United States and led by General Lon Nol. Sihanouk, who had been exiled in Beijing, decided to throw in his lot with the North Vietnamese and the small group of Cambodian communists he dubbed “les Khmers Rouges.” By making common cause with the latter and assuring the rest of the world of their benign intentions, he endowed them with a measure of legitimacy and political prominence that had earlier eluded them.Footnote 4 Between 1970 and 1975, the “carpet-bombing” of Cambodian territory by the United States and the radical insurgent tactics of the Khmer Rouge made it increasingly difficult for peasants to live on the land, destroying the agricultural economy as well as the fabric of Cambodian peasant society. On April 17, 1975, following a series of victories in provincial cities throughout the country, the black pajama-clad peasant soldiers of the Khmer Rouge seized the capital city of Phnom Penh and ousted Lon Nol's government. The very same day they embarked on a radical Maoist agrarian program to return the Cambodian economy and society to “Year Zero,” emptying the city and forcing people to migrate to provincial labor camps. In September of the same year, the Khmer Rouge brought Sihanouk back to a ghost city and declared him the titular head of state. He resigned in April 1976 and was held captive on the grounds of the royal palace for three years until he returned to exile in Beijing. The infamous Pol Pot became prime minister at the head of the Democratic Kampuchea regime and Cambodia was governed by the reign of terror imposed by the Khmer Rouge's ruling party organization known as the Angkar.

The horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime and the genocide it perpetrated have been well documented.Footnote 5 Over one million Cambodians, out of a 1975 population of about 7.5 million, are estimated to have been killed through outright execution, starvation and disease, and the physical burdens of forced labor.Footnote 6 In addition to carrying out indiscriminate murderous rampages, the Khmer Rouge systematically destroyed the very fabric of Cambodian society by targeting for execution and displacement the most educated and trained sectors of society – including teachers, lawyers, doctors, and Buddhist monks, as well as the Vietnamese and Chinese leaders of the commercial class. The Khmer Rouge operated a network of prisons and execution centers, the most infamous of which were Tuol Sleng, or S-21, in Phnom Penh, and the Choeung Ek “killing fields” on the outskirts of the city. The chilling phrase widely repeated by Khmer Rouge cadres as they carried out their purges of “enemies of the revolution” was “To keep you is no gain; to kill you is no loss.”Footnote 7 Over time, as the small inner faction around Pol Pot became increasingly paranoid, the organization also purged its own ranks. The Khmer Rouge decimated Cambodia's small elite and crushed any forms of dissent, destroying in its wake the country's civic institutions and all forms of community and religious association.

In parallel to these assaults on their own people, the Khmer Rouge carried out numerous attacks against Vietnam. The Vietnamese finally retaliated with an invasion, driving the Khmer Rouge out of Phnom Penh in January 1979 and installing a Hanoi-backed client regime, the self-styled People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), headed by defectors from the Khmer Rouge. Vietnam, with the full support of its Soviet patrons, thus liberated Cambodia from the Khmer Rouge's grip at the same time as it installed an occupying regime there. Almost no country outside the Soviet bloc recognized the new regime in Phnom Penh. The Khmer Rouge retained the country's UN seat, passing it in 1982 to the newly formed Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK). That coalition was headed by Sihanouk and included three armed Cambodian resistance groups: the Khmer Rouge; Sihanouk's royalist political party FUNCINPEC (National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia);Footnote 8 and the non-communist Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF). External involvement became further entrenched, with the Chinese arming the Khmer Rouge, and the United States, Britain, and France supporting the other coalition partners. Schisms in the domestic elite became hardened by the logic of these Cold War alliances. In turn, Cambodia's societal and political divisions deepened and persisted after the civil conflict was brought to an end.

Its lack of UN recognition notwithstanding, the PRK regime controlled the country from 1979 onward. When Vietnam withdrew in 1989 it became known as the State of Cambodia before subsequently restyling itself as the Cambodian People's Party in order to contest the UN-administered elections in 1993. It was led by Heng Samrin and then Hun Sen, both Cambodian-born Khmer Rouge defectors with strong ties to Vietnam. This regime “developed out of the devastation inherited from the Khmer Rouge an effective (albeit dictatorial) authority over more than 80 percent of the territory”Footnote 9 and rebuilt and controlled the organs of the state. Yet it lacked legitimacy on both international and domestic fronts.Footnote 10 The PRK was nowhere near as brutal as the Khmer Rouge, but it remained a hardline, one-party state controlled by Vietnam. It brooked no dissent, cracked down on opponents, sometimes through the use of torture and murder, controlled the judiciary and press, and stifled civil society. The PRK also had to contend with the Cambodian population's widespread mistrust of, and distaste for, the Vietnamese. Few in the country supported the regime and few Cambodians returned from the diaspora to assist it with governing the country.

In this context, the PRK faced a major challenge in constructing a viable political order. In essence, it was an illegitimate occupying regime that needed to extract resources and some form of legitimacy from the provinces in order to govern the country from the center. It did so by constructing an extensive patronage network throughout Cambodia, primarily through a strategy of delegation that enabled personal gain for co-opted provincial officials while ensuring some measure of governance and public goods provision throughout the country. Caroline Hughes observes that the PRK's statebuilding project “comprised the establishment and cementing of clientelist networks running through the ministry, military, and provincial structures” that drew upon the cultural repertoires of clientelism that had long characterized Cambodian governance.Footnote 11 Political order rested upon, and power came to be deployed by, instrumental and highly personalized clientelist ties between top elites and the agents upon whom they relied to carry out their orders. In a classic manifestation of a neopatrimonial hybrid order, this led to the evolution of flexible, informal, even evasive, administrative and political cultures, in combination with a hierarchical and cohesive party patronage structure that penetrated Cambodia down to the village level, where kinship and patronage ties remained the basis of customary Khmer peasant relationships.Footnote 12

The PRK mirrored earlier governing strategies deployed by Sihanouk and even Lon Nol, who, while personalizing political control, similarly tried to extend the reach of the state out to the rural areas of the country. This twin tactic served to extend the scope of patrimonial and patronage-based politics.Footnote 13 Yet the reach of the state under the PRK extended even further down to the village level. The regime consolidated the dominance of its party apparatus, concentrated political control, and lengthened the hierarchy of patron–client relationships by introducing, for example, a three-member village committee that comprised appointed representatives, as well as rice cooperatives, which collectivized rural agricultural production.Footnote 14 The extensive reach of the PRK state apparatus into the Cambodian countryside had major consequences during and after the international peacebuilding intervention.

The competition for political control over the country developed out of the collapse of the legitimacy of the Cambodian state, which had begun in earnest under the Khmer Rouge's violent regime and continued under the Vietnam-installed regime. The PRK regime and its Vietnamese and Soviet backers considered the civil conflict against the Khmer Rouge to be a necessary counterinsurgency waged against a genocidal opponent. The CGDK coalition and its UN and US supporters saw the roots of the conflict in the armed intervention and occupation of the country by Vietnam.Footnote 15 The difficulty of finding a bargain that was palatable to all these competing sets of interests prolonged the conflict.Footnote 16 As Doyle and Sambanis succinctly observe, the challenge of building a peace in Cambodia was the challenge of joining effective government – the PRK – with legitimate sources of authority – the exile coalition, led by Sihanouk.Footnote 17 That disconnect between effectiveness and legitimacy has continued to thwart the Cambodian peacebuilding process to the present day and it remains the defining obstacle to constructing a modern political order in the country.

The Paris Peace Agreement on Cambodia

The Cambodian civil war was finally ended by the Paris Peace Agreement – the centerpiece of which was the Agreement on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict. This peace deal was arrived at by Cambodian elites as their various external backers withdrew support in the waning years of the Cold War. The settlement was intended to be a firm coda to the long battle for control of the country. Instead, it served as the preface to the next phase of the elite conflict that had long divided Cambodia. The negotiations in the run-up to the Paris Peace Agreement highlight the deeply entrenched animosities between the Cambodian factions – and reveal that the final agreement resulted from changes in the geostrategic context rather than from any real domestic political rebalancing. Vietnam began to consider the possibility of compromise between its client regime and the other Cambodian contenders to power as Soviet support for the PRK began to diminish in the mid-1980s and Vietnam sought closer ties with its Southeast Asian neighbors.Footnote 18 In November 1987, Sihanouk had his first meeting with the PRK's leader, Hun Sen, to begin negotiations for a political settlement. In addition to the rapidly changing geopolitical context, Doyle observes that other factors, such as Sihanouk's age, Hun Sen's aspiration for international recognition, and military exhaustion on all sides, helped prompt these talks, as did the increasing desire of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to see a resolution to the conflict.Footnote 19 Informal meetings – facilitated by an ASEAN eager to assume a regional leadership role – identified the need for some degree of interim international involvement over the full transition to peace without any agreement on what that mechanism would look like.

In the search for a comprehensive settlement, the first Paris Conference on Cambodia was convened in July 1989. Yet these talks stalled initially, deadlocking over the nature of the interim control mechanism as well as the issue of power-sharing among the Khmer factions. The notion of a UN trustee-like interim administrative supervision of Cambodia was first mooted at this time.Footnote 20 A power-sharing system was proposed, whereby the control of several crucial ministries – defense, public security, finance, information, and foreign affairs – would be shared across the four major competing factions, along with additional mechanisms for scrutiny and oversight. The PRK, however, balked at allowing Khmer Rouge participation in the proposed interim quadripartite government; and the CGDK coalition of the other Khmer factions was leery of legitimizing the Vietnam-installed government in Phnom Penh and granting it an advantage in any future elections. Vietnam removed its troops from Cambodian soil in 1989, intent on normalizing relations with the United States, China, and ASEAN. Hun Sen's government, known formally from 1989 onward as the State of Cambodia (SOC), was left behind, still in control of the country. Yet the civil war continued, with the Khmer Rouge continuing to make territorial advances at the end of the 1980s. Finally, in 1990, the Permanent Five (P5) members of the UN Security Council drafted a peace plan that called for the establishment of an interim administration made up of the four factions to run the country under UN supervision. By this time the context had changed sufficiently to put in place the institutional arrangement that had earlier been rejected. The parties to the conflict agreed to this framework, although coming to a workable peace settlement took another year.

The Agreement on a Comprehensive Political Settlement of the Cambodia Conflict was signed in Paris on October 23, 1991. In this peace settlement, the four warring parties agreed to a ceasefire and disarmament, as well as refugee repatriation, the re-establishment and maintenance of law and order, the promotion of human rights, and principles for a new constitution committed to democratic pluralism. This negotiated peace was to be pursued in the context of UN administrative supervision and a UN-managed election. The Paris Peace Agreement was thus the genesis of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). The agreement also mandated that the Supreme National Council (SNC), a quadripartite body created in the run-up to the final peace deal and endowed with Cambodian sovereignty and authority, would become the ongoing institutional manifestation of the temporary consensus achieved at the Paris Accords. The SNC would hence serve as UNTAC's parallel domestic counterpart during the transitional governance phase.

Yet the Cambodian factions did not sign the Paris Peace Agreement (sometimes also referred to as the Paris Peace Accords) out of their own desire for peace, but did so unwillingly due to the pressure applied to them by their external backers as a result of the changing geopolitical context.Footnote 21 Each of the parties continued to view itself the rightful regime to govern the country. The SOC believed itself to be in control of 90 percent of the country, while the Khmer Rouge believed it could continue to mount a guerrilla war and later did so. These “competing conceptions of how the accords would affect them…undermined the consent critical to peacekeeping.”Footnote 22 It appears that each group agreed to the institutional terms of the settlement while planning to manipulate and even subvert them as best they could moving forward. In practice, this meant that if the parties saw the UN as acting against their interests they would react with entrenched resistance – an approach that often led to impasse. The SOC and the Khmer Rouge actively resisted UNTAC whenever it sought to implement its mandate in a manner that they perceived to be against their interests. Perhaps most significantly, the Khmer Rouge refused to comply with the second phase of the ceasefire in June 1992, which included the cantonment, disarmament, and partial demobilization of each of the factional armies. The SOC used this refusal to disarm as its own justification for resisting UNTAC control and soon the two factions were once again engaged in violent conflict – with each other, against opposition party officials, and even targeting civilians and UNTAC staff – as the election neared.

The resolution of the Cambodian conflict through the Paris Peace Agreement, albeit facilitated by external powers, serves as an example of how a “mutually hurting stalemate” can, as described by William Zartman, result in a convergence of preferences in the form of a peace treaty.Footnote 23 Yet although the Paris accords represented an inflection point in the Cambodian civil conflict, the peace settlement did not mark a final resolution to the civil war. In many ways, and increasingly so over time, subsequent Cambodian reconstruction occurred within the context of deep political animosity that sometimes simmered over into violence and instability and compromised the goals of the peacebuilding process from being achieved.

The East Timorese Resistance to Occupation

East Timor's national independence referendum in August 1999 marked the final victory of the country's 24-year-long fight for freedom. The challenges of constructing political order in East Timor emanate from both its long Portuguese colonial history and the shorter, yet traumatic Indonesian occupation.

The eastern half of the island of Timor was colonized by Portugal in the sixteenth century. Initially, the Portuguese ruled indirectly, through the traditional Timorese kings, or liurai. Binding together the country in the face of its ethnolinguistic diversity was a ritualized web of exchange relationships and political alliances, travel for trade and social purposes, and the spread of Tetum as the common indigenous language.Footnote 24 In the nineteenth century, Portuguese rule shifted toward greater territorial administration and became increasingly intrusive. The country's administrative division into villages, or sucos, disrupted the traditional political order associated with the liurai, who rebelled against their colonizers in 1912. The crushing of this rebellion ushered in a stable period until 1975. With the liurai acquiescing to the Portuguese administration, the traditional political order was overlaid by a new colonial order that empowered the mestiço Timorese – those with blood ties to Portugal. This colonial order created, in turn, a deep, lasting – and, later, politically salient – social cleavage between the urban, mostly Portuguese-speaking and Portuguese-oriented elite and the “Maubere” mountain people, who retained their traditional names, languages, and beliefs. The lives of the latter, who constituted the vast majority of the Timorese population, were relatively untouched by the centuries of Portuguese colonization, which had done little to build national institutions or infrastructure.Footnote 25 Overall, the colony's political and institutional development, particularly at the subnational level, had been severely attenuated. The legacies of this under-institutionalization, weak local capacity, and marginalization of the majority of Timorese from their country's governance have remained major challenges in the construction of political order in the country.

In 1974, Portugal's “Carnation Revolution” brought to power a new government in Lisbon that set in motion the dissolution of the Portuguese empire by accepting the right to self-determination of its colonies, even if they chose independence. Nascent political actors in East Timor quickly mobilized into three major competing political parties that espoused different positions with regard to the issue of self-determination. The Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) was the most conservative group, comprising the more prosperous Timorese and administration officials, many of whom were mixed race Portuguese–Timorese. UDT leaned toward the status quo, favoring a long transitional period of 15–20 years of autonomy with continued association with Portugal prior to full independence.Footnote 26 The Timorese Social Democratic Association (ASDT) advocated a quicker move to independence. In a sign of how close the parties’ original political stances were, however, ASDT still began with a desire for an 8 to 10-year transition period of progressive autonomy, giving the country time to build its political and economic infrastructure. When its political program adopted a more radical tack a few months later, with more strident demands for Timorese inclusion in the administration and a clear demand for independence, ASDT became the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN).Footnote 27 The Timorese Popular Democratic Association (Apodeti), finally, was a smaller party that desired the integration of East Timor as an autonomous province within Indonesia. As James Dunn observes: “The polarization of the three main parties around three distinct goals tended to exaggerate the differences between their young leaders in that early stage of the territory's political development.”Footnote 28 Yet the lines had been drawn early and would harden quickly.

In January 1975, UDT and FRETILIN, the two pro-independence parties, formed a short-lived coalition.Footnote 29 Initially, there was little difference between the viewpoints and aspirations of the leaders of these two groups. Yet FRETILIN became increasingly radical and it hardened its attitude toward other parties; while UDT moved to expel FRETILIN radicals in order to build a more conservative coalition. In a relatively short period of time, the alliance collapsed and there was subsequently a rapid escalation of the hostility between the parties. By the second half of 1975, East Timor was engulfed in a brief yet violent civil war that resulted in both urban fighting and intense battles among rural villages with competing party allegiances. In August of that year, the Portuguese governor and administration left Dili, withdrawing to the nearby island of Atauro and washing their hands of the East Timorese political situation.

FRETILIN had emphasized building its political organization across the country, outside the main towns where UDT operated, and its political strategy paid off. It was able to quite quickly gain control of much of the territory and forced UDT out of Dili within weeks. Its relatively loose political organization proved surprisingly adept at the formidable tasks of setting up a provisional administration and restoring law and order and basic services. As a result, by mid-October 1975 Dili was functioning normally. This was despite the fact that waves of Timorese refugees to both Australia and Indonesia, along with the withdrawal of the Portuguese administration, led to the loss of approximately 80 percent of East Timor's officials – leaving a particular lack of administrative personnel at the district level.Footnote 30 FRETILIN leaders recognized their administration could only be temporary and called on the Portuguese to return and implement a phased decolonization process. FRETILIN's successful, albeit brief, interregnum – whereby it established its populist and nationalist roots down at the village level and entire sucos shifted allegiance to it based on village chief preferences – forged a strong emotional bond between the party and the Timorese people, and had a lasting impact on the national psyche. By sending its young cadres out into rural areas to work on agriculture and literacy programs, FRETILIN “captured peoples’ hearts.”Footnote 31 Dunn estimates that FRETILIN's support had, by September 1975, risen to 80 percent of the population from its initial 60 percent in elections a couple of months earlier.Footnote 32

Meanwhile, Indonesia had embarked upon a program of subversive activities intended to destabilize the country and undermine FRETILIN's claim to authority over all of East Timor, with the goal of providing the pretext for Indonesian occupation through ties with the integrationist party, Apodeti. In October 1975 Indonesia began a series of covert attacks, codenamed Operasi Komodo, to perpetuate the notion that the civil war between FRETILIN and UDT was ongoing. The FRETILIN leadership's main preoccupation became blocking Indonesia's designs over the country, preventing instead a deeper attention to reconstructing the administration and economy. FRETILIN appealed in vain to Indonesian President Suharto and the rest of the world for a negotiated solution. Its sense of isolation grew, along with the recognition that its energies would have to shift from building a new administration to defending the country. The leadership began to make preparations for a guerrilla struggle against Indonesia, sending food, supplies, and arms into the mountains.

The denouement came when Portugal agreed in November 1975 to talk with Indonesia over the status of the territory with no UN or Timorese representation. Although FRETILIN leaders realized they were in no position to govern an independent country, they unilaterally declared the independence of East Timor on November 28, 1975. Two days later, a coalition of pro-Indonesia parties, comprising mainly UDT and Apodeti, also proclaimed the independence of the territory from Portugal and its integration with Indonesia. East Timor had never been part of the Dutch East Indies, and Indonesia had never laid any formal territorial claim to the country. Yet, on December 7, 1975, Indonesia launched a naval, land, and air invasion of East Timor, under the pretext of preventing instability in its neighbor and eradicating what it identified, to promote Western acceptance of its invasion, as the radical leftist independence parties there.

The initial Indonesian assault was brutal. The many incidents of violence included the summary mass executions of hundreds of Timorese and Chinese residents and the abduction, torture, and rape of women and girls affiliated with FRETILIN. The remnants of the Portuguese colonial administration on the island of Atauro bore witness to the first day's assault and set sail the next. Dili was ransacked first; but similar mass executions took place in the towns of Liquiça, Maubara, and Aileu as the Indonesians extended their grip on the country. In response to the savage onset of the invasion, many Timorese fled their homes: tens of thousands fled to West Timor and, in the eastern half of the country, tens of thousands moved their households behind rebel lines in the mountains. In the area around the FRETILIN stronghold of Baucau, for example, the local population fell from about 85,000 people prior to the invasion to about 32,000 three months later and less than 10,000 a year after that.Footnote 33 All told, two-thirds of the remaining Timorese population were behind rebel lines during the course of the occupation.Footnote 34 Those who chose to surrender once famine conditions took hold in the mountains were placed in resettlement camps in which the conditions were equally dire.

Indonesia gradually increased its territorial control at FRETILIN's expense, continued its alliance with the pro-Indonesian parties, and perpetuated the fiction that the Timorese people supported the Indonesian presence. A “Regional Popular Assembly” was established to determine the status of East Timor and this carefully Indonesian-assembled group petitioned Indonesia on May 31, 1976, to formally integrate East Timor. Six weeks later, Indonesia's President Suharto promulgated a law integrating East Timor into his country as its twenty-seventh province. From that point onward, Indonesia maintained that the East Timorese people had exercised their right to self-determination and had chosen integration with Indonesia, albeit under autonomous status.Footnote 35 Portugal, however, never ceded its governing authority over East Timor and the United Nations declined to recognize the authority of the Regional Popular Assembly concerning the status of East Timor. The country was all but under an Indonesian military occupation, a fact made possible by American and Australian silence on the issue.Footnote 36

FRETILIN continued to resist East Timor's integration into Indonesia, retreating into the interior mountains of the island and fashioning itself into a guerrilla movement with an armed wing, FALINTIL (Armed Forces for the National Liberation of East Timor). Few Timorese were in favor of integration to begin with, and Dunn notes that “the rapacious and brutal behavior of the occupying forces greatly stiffened the resolve of the resistance and provided FRETILIN with a degree of popular support greater than it might otherwise have enjoyed.”Footnote 37 From mid-1976 onward, the pattern of Timorese resistance shifted firmly from political action toward guerrilla warfare, and FRETILIN devoted considerable attention to ensuring adequate food supplies for the swollen mountain population.Footnote 38

The Indonesians made some attempts to revive East Timor's economy, but they concentrated their attention on those sectors from which they could derive the most rents. The majority of Timorese who refused to accept the Indonesian citizenship necessary for a government job found very few formal employment opportunities available to them. Although some Timorese officials and politicians accepted positions of authority under the new administration, the undisputed leaders of the territory were Indonesian officers from the armed forces, Tentara Nasional Indonesia (TNI), and the Kopassus special forces units. East Timor became an important financial resource and symbol to the Indonesian military elite – a fact that later fed into the TNI-inspired post-referendum violence in 1999. The political and economic marginalization of East Timorese under Indonesian occupation was more extreme than under Portuguese colonization.

FRETILIN's political and military structure coalesced during the initial years of the occupation. Nicolau Lobato became the main leader of the resistance, overseeing both political and military strategy, as other leaders who favored a negotiated settlement with Indonesia were gradually purged from the organization. Lobato was killed in 1978 and the death of this folk hero was to prove a major symbolic setback for the Timorese.Footnote 39 Caroline Hughes notes that this period marked a shift in resistance tactics: with major Indonesian assaults being stepped up against the ground it held, FRETILIN yielded its territorial control and FALINTIL units moved to secret mountain hideouts from where they initiated a new strategy of insurgent attacks on the Indonesian army.Footnote 40 Communication was essentially cut off between the guerrilla leaders in East Timor, their FRETILIN colleagues in exile in Mozambique, and the Timorese diaspora in Australia and Indonesia. The group of FRETILIN leaders in Mozambique, who came to be known as the “Maputo clique,” held on to the original radical beliefs and motivations established during the movement's formation. The guerrilla leaders on the island, meanwhile, adapted their beliefs and objectives to the exigencies of continuing the insurgency and caring for the population still behind their lines.

José Alexandre “Xanana” Gusmão – later East Timor's first president, and then two-term prime minister for seven and a half years – assumed command of FALINTIL and the domestic mantle of FRETILIN leadership over the course of a two-year period from 1979 to 1981. He took deliberate steps to move the group's political tactics away from radicalism and toward non-ideological policies intended to appeal to all Timorese. He formed the National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRM) – later renamed the National Council for Timorese Resistance (CNRT) – which was intended to serve as an umbrella national resistance movement with a broader political appeal than FRETILIN. In so doing, he and other key guerrilla leaders embraced the ideology of Mauberism, identifying the Timorese nation with the Maubere mountain peasants and their traditions and idealizing the relationship between the FALINTIL guerrillas and the mountain people in a bond that remains politically symbolic to the present day.Footnote 41 In this manner the urban elite core of FRETILIN and the rural poor Maubere majority were joined together in a newly fashioned contemporary Timorese nationalist identity – a central plank upon which today's political order rests.

From 1982 onward, Gusmão was able to establish communications with FRETILIN leaders abroad, particularly those who had been orchestrating the party's political organization and objectives from exile in Mozambique and, in the 1990s, the Timorese diaspora in Australia. FALINTIL's strength in terms of the number of fighters and its overall military capability declined from the mid-1980s onward but the CNRM built and maintained an extensive network of popular support in the towns and villages of East Timor. Its survival and success as a resistance front depended on this grassroots network. Gusmão undertook what became a legendary walk from village to village across the interior of the country, asking the people whether FALINTIL should continue the resistance and generating an enormous groundswell of support.Footnote 42 During this time he was given the title “brother of the roots,” or Maun Bo't, by the people and, together with the FALINTIL troops he led, attained a heroic status among the Timorese population, serving as a symbol of their resilience as a nation and a reminder that Indonesian occupation was neither complete nor final. Gusmão was arrested in 1992, but continued to command FALINTIL from prison in Jakarta. Over the course of the next decade, he became a key interlocutor between UN and other negotiators and the FRETILIN leadership, cementing his role as the key veto player in Timorese politics.

Over the course of the latter half of the occupation, other elements of the Timorese political landscape began to take shape as various groups of political actors gained in importance. The Catholic Church assumed a growing political role in East Timor, with later Nobel Peace laureate Bishop Carlos Belo arriving on the scene in 1983. In addition, political activism blossomed among the Timorese youth. They were products of an Indonesian education system that was intended to make them more sympathetic to integration. Yet, speaking the Bahasa language in which they were educated, they formed a new front against integration with Indonesia, having equally experienced – or at least witnessed among their families – the brutality, oppression, and human rights abuses that resulted from the occupation. As the guerrilla movement neared exhaustion in the late 1980s, the student movement became crucial in the final years of the fight for freedom, as well as in the political settlement that was to come with independence. From 1995 onward, the UN convened an annual meeting of East Timorese leadership, known as the All-Inclusive Intra-East Timorese Dialogue, which drew delegates from both inside and outside the country. This event was significant in bringing together the disparate strands of the Timorese leadership, although the representatives from inside East Timor tended to lean toward Indonesia and Gusmão himself was not present.Footnote 43

The conflict lasted through 1999, with particularly heavy loss of life in its vicious early years. Estimates of the number of Timorese who died as a result of the independence struggle, including from the famine and disease that came with massive population displacement, range as high as 200,000; the Indonesian authorities themselves acknowledge up to tens of thousands of deaths.Footnote 44 The human rights violations committed by the Indonesian army against FRETILIN cadres and their supporters were extreme. Indonesian missions behind guerrilla lines deliberately destroyed food crops to create conditions of destitution. In the infamous “fence of legs” campaign, the Indonesian army forced thousands of East Timorese villagers to march in human chains ahead of Indonesian troops to comb the interior of the island for FRETILIN and FALINTIL members. Dunn reports that in a second “fence of legs” campaign in 1985, thousands of Timorese chose to go to the hills to avoid conscription, resulting in famine conditions, torture, and executions.Footnote 45 The brutality of the Indonesian troops against the guerrillas intensified the local population's hostility toward the occupiers, even turning Timorese youths into faithful FALINTIL recruits.

These human rights violations received little attention abroad until November 1991, when Indonesian armed forces opened fire on a pro-independence assembly of mourners at Santa Cruz Cemetery in Dili, killing at least 50 and possibly up to 200 people. The television images and journalist reports from the scene had a dramatic impact on the international community, raising East Timor's profile in the global consciousness. In 1992, Xanana Gusmão's own profile, and that of the movement he led, was elevated when he was captured and subsequently continued his activism from prison. Then, in 1996, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Dili's Bishop Belo, who, among other things, had played a crucial role in exposing the Santa Cruz massacre, and José Ramos-Horta, FRETILIN's exiled foreign minister and leading international spokesman, “for their work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor.”Footnote 46

The United Nations had remained essentially a bystander during the course of the occupation.Footnote 47 The Security Council adopted resolutions in December 1975 and April 1976 that affirmed the right of the East Timorese to self-determination and called on Indonesia to withdraw. Through 1981, the General Assembly passed annual resolutions expressing concern over the suffering of the East Timorese population and reaffirming their right to self-determination. Direct discussions between Portugal and Indonesia were initiated under the auspices of the Secretary-General in 1983, yet they failed to achieve any progress. Indonesia maintained that the Timorese had decided on their fate in 1976; Portugal, however, insisted on a legitimate act of self-determination in East Timor, thereby keeping the issue alive. Tripartite talks were revitalized and the UN role became more proactive when Secretary-General Kofi Annan appointed a Personal Representative for East Timor in February 1997.

The East Timor Independence Referendum

The Indonesian occupation of East Timor was finally brought to an end by internal changes in Indonesia, beginning with the fall of Suharto in May 1998. The following month President B. J. Habibie, Suharto's successor, floated an offer of autonomy to East Timor, which was still under integrated status. The Indonesian military was staunchly opposed to any concessions that could lead East Timor down the road to independence. Special forces officers based there began setting up an extensive paramilitary organization made up of pro-integration Timorese, intended to frustrate a possible referendum. The Indonesian military paid, trained, and armed militia members and organized their operations against pro-independence groups. Militia violence – including seizures of independence activists, torture, killings, and the destruction of homes – began in October 1998 and escalated in early 1999. By that point, FALINTIL troops had moved into cantonment in the mountaintop town of Aileu and followed the still imprisoned Gusmão's order not to engage either Indonesian or paramilitary units, so as not to allow any further civil war pretext for continued Indonesian occupation. The decision was followed with agonized restraint at the time as FALINTIL troops watched their countrymen being murdered; it has since been credited as a crucial strategic move that facilitated a faster and more inclusive national healing process.Footnote 48

Gusmão and other Timorese leaders remained firm on their demand for an eventual referendum on independence but were amenable in early 1999 to an extended period of transitional autonomy, in which Indonesia would play an active role, before a vote.Footnote 49 Yet Indonesian officials in Jakarta objected to the transitional autonomy approach, believing that a majority of Timorese would choose to remain in Indonesia and advancing the sentiment that they would rather withdraw entirely if the Timorese chose independence. Indonesia, Portugal, and the UN finally reached agreement, on May 5, 1999, to hold a referendum on whether the people of East Timor accepted Indonesia's integration-with-autonomy proposal. Although the independence option was not specifically on the ballot, it was clearly the alternative in the Yes–No vote; Habibie declared that if the Timorese voted against autonomy, he would call on the Indonesian parliament to grant them independence.

The UN moved quickly to organize the plebiscite, with the Security Council establishing the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) on June 11, 1999, to manage the voting process. The UN had a little over two months to organize a free and fair vote – including the registration of eligible voters, the organization of the vote itself, and the establishment of a secure environment. This latter security concern was paramount – yet Indonesia refused to accept international peacekeepers, insisting that it alone must remain responsible for ensuring security during and after what it called the “popular consultation.” Pro-integration militias directed by the Indonesian military ratcheted up their violent campaign, focusing on districts adjacent to the border with West Timor and forcing thousands of East Timorese to flee their homes and cross the border.

On August 30, 1999, in the midst of that intimidation, East Timorese voted in a national referendum – known as the Popular Consultation in East Timor – overwhelmingly against a special autonomy relationship with Indonesia and hence in favor of independence.Footnote 50 The country had finally been allowed the act of self-determination it had been promised in 1974 by a withdrawing Portuguese colonial administration. Just hours after the results of the referendum were announced, pro-special autonomy militias – still organized, armed, and assisted by the retreating Indonesian military forces – conducted a pre-planned, systematic “scorched earth” campaign intended to leave the small country both depopulated and in ruins.Footnote 51 Some three-quarters of buildings in the country were gutted by fire and demolished in the retreat. An estimated 80 percent of the nation's 800,000 people fled their homes to escape the violence, with about a quarter of a million displaced persons fleeing and being forcibly deported into neighboring West Timor, where it is estimated that around half of them remain today. Estimates of how many were killed are unreliable, varying from hundreds into the thousands; some mass graves remain unexamined, reports abound of bodies being dumped at sea, and many who fled to West Timor are subsequently unaccounted for. Gusmão's orders to FALINTIL to remain disengaged were tested to the limit as the fleeing East Timorese flocked to the FALINTIL cantonments with accounts of violence, yet they remained firm and were obeyed. The head of UNAMET, Ian Martin, later observed that the UN's planning around the aftermath of the referendum had been “on the basis of a best-case scenario that the UN hoped could be realized with a high degree of international attention and pressure but that was never realistic.”Footnote 52

Following two weeks of concerted international pressure, on September 12, 1999, Indonesia finally and reluctantly agreed to the presence of UN troops to help restore security. A multinational blue helmet force (INTERFET), headed by Australia, arrived in Dili on September 20, 1999, in one of the swiftest responses in the history of UN peacekeeping. Within two weeks the Indonesian troops had withdrawn totally and on October 20, 1999, the Indonesian parliament annulled its 1976 annexation of East Timor, bringing the occupation to a formal end.Footnote 53 Just five days later, on October 25, the UN Security Council authorized a mandate for the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET),Footnote 54 which became the governing authority of the territory for a transitional period that would culminate in national elections and the writing of a constitution. As UNAMET and then UNTAET were constituted, responsibility for East Timor within the United Nations shifted from the Department of Political Affairs, which had handled the ongoing dialogue since the 1980s, to the Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Critics later pointed to this switch in assessing the UN's role and actions in East Timor, arguing that the basic peacekeeping-oriented structure of the mission hindered it from achieving its mandate, which required the mission to govern the country as well as put in place the foundations for political, institutional, and economic development.Footnote 55

East Timor was thought by many at the UN and in wider international intervention circles to be a tabula rasa upon which to prove the effectiveness of internationally assisted peacebuilding and reconstruction initiatives. In many respects, the country appeared the perfect environment for success: violence was effectively over after the Indonesian withdrawal and there was remarkable political accord and goodwill within the country, with no real dissent over appropriate leadership. Yet UNTAET has subsequently been heavily criticized for the manner in which the political timetable and process was implemented.Footnote 56 The peacebuilding challenge in East Timor was viewed as very different from that in either Cambodia or Afghanistan. Unlike in most other UN peacekeeping missions, the main political challenge in this case was not to mediate between factions that had been at war. Anthony Goldstone captures the thinking at the time with the observation that the political adjudication process had already occurred with the national referendum in August 1999; so that “Instead, the political task was the relatively straightforward one of working through a political timetable that had the uncontested goal of independence as the final end point.”Footnote 57 A set of interrelated challenges arose over the course of this process, however, that proved problematic for subsequent state capacity-building and democratic consolidation: UNTAET's slow incorporation of East Timorese participation into both the administrative and political arenas; the clear dominance of one party as political participation was increased; and the overall timing and sequencing of the political process in relation to the statebuilding dimension of transitional governance. Furthermore, it has become apparent with the advantage of hindsight that the international community misinterpreted the domestic political situation, in particular overestimating the degree of elite political accord and the extent to which the returned FRETILIN leadership spoke for their fellow political leaders.

The Afghan Civil War

By the time the Afghan Northern Alliance and the US military drove the Taliban out of Kabul in November 2001, Afghanistan had suffered over two decades of war. Often labeled the last proxy battleground of the Cold War, the country saw its anti-imperialist war against the Soviet Union morph into a civil war among mujahideen (or freedom fighter) factions, many supported by external patrons, that combined in rapidly shifting alliances. The conflict continued into 2001 even as the Taliban, one of those factions, had consolidated power over most of the country. Afghanistan in 2001 was considered the quintessential failed state, an institutional vacuum in which societal anarchy persisted and in which state-sponsored terrorism could flourish. The country was characterized by severely fragmented social and political structures and a nonexistent central state infrastructure. It was trapped in a regional conflict complex – centered around the drug, gem, and transit trades – with entrenched subnational and transnational social linkages that perpetuated the country's internal fragmentation and chaotic conflict patterns.Footnote 58

Afghanistan has for centuries been victim to conflict emanating from both within and without – its territory being fought over in fierce tribal power battles as well as serving as a buffer between empires and contested ground for their expansionist ambitions. Modern Afghanistan was founded in the mid-eighteenth century when Ahmad Shah Durrani united the Pashtun tribes and established a political order strong enough to be the basis for territorial expansion. Yet this stability, and Afghanistan's subsequent independence, proved fragile in the face of the century-long battle between Britain and Russia for conquest of Central Asia and Afghanistan, dubbed the “Great Game.” The nation was finally consolidated in the late nineteenth century, when Abdul Rahman Khan, also of the Durrani chiefly clan, reigned over a period in which external interests over the country were balanced, the Afghan tribes were consolidated, and the country's bureaucracy was reorganized into what can be regarded as the modern Afghan state. He achieved this consolidation at a great cost in terms of violence, albeit couched in a nationalist narrative, advancing a process of what Louis Dupree called “internal imperialism” to crush different claims to authority across the country and reward followers with government posts and the spoils attached to them.Footnote 59

Establishing central government over the diverse, tribal, and independent-minded Afghan people has remained an ongoing challenge for successive rulers. One particular defining cleavage in Afghan politics has been the tension between a reformist, modernizing urban elite and a more conservative, traditional rural majority. The Pashtun monarchy was long at the fault line of this tension, claiming its legitimacy from its tribal chiefly roots but also embarking upon cautious modernization programs. It was finally abolished in 1973 when the last king, Zahir Shah, who had reigned for four decades, was ousted by his cousin and former prime minister Mohammed Daoud Khan. Daoud established rule as president of the Republic of Afghanistan and with his coup the pendulum of power in the republic swung in favor of Kabul-centric elite politics to the extent that the regime was faulted for not incorporating leaders from outside the immediate circle surrounding Daoud. Barnett Rubin labels this era of Afghan politics a “rentier regime,” in the sense that these Kabul elites were resourced by and beholden to external patrons.Footnote 60 As a result, they were motivated more by external forces than by internal ones and the capacity of the Afghan state to govern the country withered away under the control of these elites. Daoud, in turn, was killed by the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) when it seized power in April 1978. The PDPA, the principal communist organization in the country, was aligned with and aided by the Soviet Union and represented the first group of Afghan intelligentsia to come to power in the country. The radical reforms that they introduced in the countryside undermined traditional authority and social structures.Footnote 61 At the same time, the Afghan state rapidly developed a unilateral independence on the Soviets, while aid from other sources began to flow to the various Afghan resistance groups.

In December 1979, Moscow, dissatisfied with its indirect leverage over the destabilizing government in Kabul, sent troops into Afghanistan to install a more pliable government that would allow it to assert more direct control. In response, a rural resistance movement comprising various Afghan militias, or mujahideen factions, and backed by foreign support, united in order to drive out the invaders. After ten costly years of a war of attrition it found itself unable to win, the Soviet Union withdrew its troops from Afghanistan between May 1988 and February 1989. Without the unifying jihadi and nationalist impulse of driving out the invaders, the mujahideen alliance soon fractured back into its separate political and military structures with their own objectives and strategies, competing for power in a country where the national institutional infrastructure had been shattered. Local divisions re-emerged and the preferences of international supporters diverged, preventing the mujahideen groups from consolidating into a plausible political alternative to the Soviet-installed Najibullah puppet regime in Kabul. Local militia commanders began to make the necessary practical deals with their opponents and foreign funders to assert their own autonomy and power. They were once again able to levy tribute payments on road transport across their territories and, often forming Potemkin shuras or village councils, received increasing amounts of foreign aid directly rather than through their umbrella parties.Footnote 62 While some attempted to forge independent political strategies, most emerged as local strongmen, reabsorbed into traditional social and political structures but increasingly emphasizing Islamism and establishing ties with religious parties. Various sources of foreign aid empowered warlords and strengthened their patronage networks, in turn further undermining traditional patterns of life and disrupting tribal social codes in the countryside.Footnote 63 The overall result was fertile ground for warlordism to flourish.Footnote 64

As conflict widened over territory and control of the Afghan state itself, broader regional coalitions formed where social control was relatively more cohesive, often along tribal or loosely ethnic lines. The fierce political competition enabled elites to make ethnicity salient as a political resource; this was a context in which conflict became partially ethnicized, rather than being provoked by ethnic tensions. Armed forces and ethnic groups were pulled back into the country's ethnoregional power networks, and a strong degree of regional autonomy developed in the face of national turmoil.Footnote 65 Rubin observes that the extent to which regional commanders could marshal autonomous political and bureaucratic organizations marked the differences among regions in the country.Footnote 66 The Pashtun areas in the South and East remained fragmented, although in the East the army of the Pashtun Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, supported by Pakistan, remained powerful. In other parts of the country regional strongmen consolidated their power in patterns that have lasted into contemporary Afghan politics. In the Northeast, Ahmad Shah Massoud, bolstered by the legitimacy of being a national resistance hero, commanded a regional capital and substantial contiguous territory along with the social network that formed the basis of Tajik power. In the North, the Uzbek Rashid Dostum still commanded over 40,000 militiamen, more than triple those led by Massoud, with whom he was still loosely allied.Footnote 67 Ismail Khan's Persian-dominated organization in the West, centered in the city of Herat, allowed him over the next decade to function essentially as an independent emir earning revenue from tolls and providing some public services to the population.

In the meantime, the Pashtun-dominated central state, still nominally under the control of Najibullah, disintegrated as the external aid that had held it together dried up. Rubin observes that the more clientelist and locally rooted tribal Pashtun culture was not well equipped to compete in the struggle for power, with the exception of Hekmatyar's organization, to which other Pashtuns turned for leadership.Footnote 68 A series of battles for control of Kabul followed – for control of the central state, indeed control over the very definition of Afghanistan – in which alliances formed around the most extensive and mobile organizations, again largely in ethnoregional patterns. These new political formations superficially evoked traditional social structure but, in reality, the traditional “micro-societies” of Afghanistan, built on tribal, ethnic, and linguistic lines, had fractured in the chaos that beset the country – in some cases actively undermined by manipulative regional power-holders – and reconstituted into new sources of power for opportunistic warlords.Footnote 69 Sarah Chayes evokes this disintegration of order in her portrait of Afghanistan, vividly relaying the contemporary consequences of the traditional concept of yaghestan, the chaotic age that befalls Afghanistan in cycles of rebirth and destruction.Footnote 70 The consolidation of national institutions proved ephemeral in the face of the constant realignment of interests; instead, patrimonialism has served as the basis of authority.

In April 1992, the Northern warlords Massoud and Dostum took control of Kabul. An interim government composed of mujahideen parties was assembled, but the state was a hollow one. All of the major revenue sources were controlled by regional councils that retained the income for their own purposes. Militias roamed the streets of the capital fighting, looting, and raping. Paradoxically, the arrival of the interim government did nothing but intensify the competition for power. Long-standing rivalries among the parties quickly escalated into a new civil war. In particular, Hekmatyar refused to recognize the agreement since it made Massoud defense minister and effectively recognized that Kabul was controlled by the northern coalition. Rubin argues that this mutual animosity quickly took on the character and dimensions of a Pashtun versus non-Pashtun battle for the control of Afghanistan, once again reinforcing the ethnicized character of post-Soviet Afghan political conflict, which had “come to be dominated by four ethnically identified armed forces:”Footnote 71 Uzbeks under Dostum, the Shia alliance Hizb-e-Wahdat including the Hazara and Ismail Khan, Pashtuns under Hekmatyar, and Tajiks under Massoud. Yet neither the strategic objectives of these factions nor the discourse around them were explicitly ethnic. Alliances were not dictated by ethnicity – cooperation between the various commanders shifted quickly and unpredictably in a cycle of continuous fighting for control of Kabul. Hekmatyar, for example, soon successfully isolated Massoud by joining with the latter's erstwhile allies, Dostum and the Shia Hizb-e-Wahdat. Interethnic atrocities mounted as the militias fought each other for control of the capital by neighborhood, shattering the city's infrastructure. Kabul still bears the scars of its physical devastation in clearly visible layers that, in 2002, residents could wearily identify with the various successive conflicts that had wreaked damage on their city.Footnote 72

At the same time, regional centers of power continued to play a dominant role in the social and political structure of the country. Particularly in the non-Pashtun areas of the North, Northeast, and West, state apparatuses and armed forces remained in place – albeit now under the control of regional strongmen rather than that of Kabul and thus forming the basis of power for the non-Pashtun groups who for the most part focused on asserting their regional autonomy.Footnote 73 The Hazaras enjoyed a great deal of independence in the central highlands territory known as Hazarajat. In the North, Rashid Dostum maintained his powerful political niche; having amassed armed forces of 120,000 men he guaranteed the security of the northern capital of Mazar-i Sharif, where the UN and other diplomatic missions moved their headquarters during this period. Ahmad Shah Massoud retained control over most of the Northeast, including the famed Panjshir Valley. In the West, Ismail Khan turned Herat into a relatively peaceful center of economic and cultural revival.

Into this fragmented sociopolitical structure stepped the Taliban in late 1994. According to the founding legend, a group of madrasa teachers and students led by Mullah Mohammed Omar formed the movement in order to end the power of the warlords, regain security in the face of the chronic anarchy, violence, and extortion that persisted under the local militias, and establish a pure Islamic regime.Footnote 74 The Taliban thus stepped into a political and institutional space that had emerged as a result of the preceding twenty years: the inter-elite battles, in which modernizing intelligentsia destroyed itself; and the collapse of state institutions after the Russian invasion and the onset of the mujahideen battles. In this space, madrasa networks became increasingly salient among a new elite while other institutional ties were being destroyed. The Taliban received significant levels of initial popular support in Pashtun-dominated areas by presenting themselves as an Islamic solution to state failure, and by establishing authority and strict order through sharia law. In so doing, the Taliban echoed the rationale of earlier Islamist parties in Afghanistan. This same rationale has, in turn, over the past decade enabled the Taliban to reassert some legitimacy in the southern parts of Afghanistan where the international community has failed to restore order and security.

Rubin points out that had the Taliban stopped at bringing order to the Pashtun areas of southern Afghanistan, “they might have joined about five other ethnoregional coalitions that existed at that time in negotiating a decentralized form of Afghan statehood.”Footnote 75 But they transformed their movement into a political and administrative organization and were backed by large amounts of military and tactical aid from Pakistan, which saw the Taliban as a new ally in place of its former Pashtun surrogate, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who had failed to hold onto power. From their stronghold in Kandahar province, the Taliban rapidly conquered territory and political power, capturing Kabul in September 1996. The mujahideen groups, having failed to establish a stable government in the face of their infighting, abandoned the capital almost without a fight. By August 1998, the Taliban controlled about 90 percent of the country's territory, thereby achieving a broader reach of authority across the country than any previous administration had been able to establish.

Within a month, however, those groups that had lost to the Taliban met in northern Afghanistan to form what became known as the Northern Alliance. This group continued to hold Afghanistan's UN seat. It was initially dominated by the Tajiks aligned with Ahmed Shah Massoud – who served as its de facto military and political leader – but also included Uzbek and Hazara groups, and even some Pashtuns. Yet with political power embedded in local strongmen and their various armed groups rather than unified a state apparatus, it had no effective organizational counterpart to the Taliban's administrative structure and could not mobilize foreign fighters as could the Taliban.Footnote 76 Afghanistan remained divided between the Taliban-controlled south and capital city and the Northern Alliance-controlled northern part of the country, into which the Taliban continued to make advances. The Taliban's rhetoric, objectives, and alliances became increasingly pan-Islamic rather than nationalist, particularly in the face of growing ostracization by the international community. Al-Qaeda, the global jihadist terrorist organization led by Osama bin Laden, became increasingly integrated into the Taliban organization through the personal relationship of the two leaders and the military alliance between the two groups.

These patterns persisted until October 7, 2001, when the United States began its bombing campaign in Afghanistan to root out Al-Qaeda and its Taliban sponsors in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In strategic partnership with the Northern Alliance on the ground, the United States helped to quickly rout the Taliban, liberating Mazar-i-Sharif on November 9 and Kabul on November 13. The Taliban abandoned even their stronghold in Kandahar on December 6, one day after the selection of Hamid Karzai, a Durrani tribal chief and former mujahideen leader, as chairman of the Afghan Interim Administration under the Bonn Agreement.

The Afghanistan Bonn Agreement

The speed of Operation Enduring Freedom, the US military campaign in Afghanistan, forced a diplomatic scramble to bring together the country's non-Taliban leadership. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan named Lakhdar Brahimi as his special representative to shepherd the process and negotiations. Events on the ground moved quickly, precipitating political responses. The day after the Northern Alliance marched into Kabul, the UN Security Council passed a resolution affirming the UN's central role in supporting Afghanistan's political transition efforts and calling for a new government that would be “broad-based, multi-ethnic and fully representative of all the Afghan people.”Footnote 77 The intense combined diplomacy of the United Nations and the United States got the main Afghan political parties to agree to convene in Bonn to choose an interim government and map out the political transition process.Footnote 78 Representatives from four key groups were present: the various factions of the Northern Alliance; supporters of the former king, Zahir Shah; Pashtun mujahideen, tribal, and religious leaders based in Pakistan; and a mixture of Shia factions with ties to Iran. As the Bonn Agreement acknowledged in its preamble, the grouping was not fully representative. Brahimi is reported to have stressed repeatedly in Bonn that few would remember that the meeting had been unrepresentative if those there successfully fashioned a process resulting in legitimate and representative governmentFootnote 79 – an assertion that appears mistaken in retrospect. Afghan civil society groups held a tandem forum near Bonn, in an attempt to have alternative voices heard in the political process. Most obviously, the Taliban was not included – nor was their loose ally, the Hezb-i-Islami faction led by the Pashtun Islamist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. The lack of representation of such spoiler groups meant later that the “Bonn process was ill designed to cope with their resurgence through political means.”Footnote 80

The Bonn Agreement of December 2001 – officially, the Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Re-Establishment of Permanent Government Institutions – was not a ceasefire agreement between belligerents. Rather, it represents a different type of peace settlement, providing the framework for further negotiations about how peace would be achieved in Afghanistan. It left for future resolution through the transitional governance process many major and contentious decisions, including, for example, questions of political power-sharing – both at the central level and between the center and the provinces – and the very nature of the Afghan state and its constitution. Nonetheless, the agreement established a series of milestones to which parties would have to adhere when the time came. The Afghan factions and the diaspora political leadership meeting in Bonn agreed, under the supervision of the UN, to the creation of an Interim Administration, endowed with Afghan sovereignty. This Interim Administration would be the main counterpart of the UN and other peacebuilding and reconstruction partners during the course of the transitional governance period. In recognition of the not fully representative agreement, the Interim Administration was to last only six months before the selection of a Transitional Administration. The Bonn Agreement also stipulated a two-year window for a new constitution to be drafted. The chairman of the interim and transitional administrations was endowed with the power to make law by decree with his cabinet's agreement.

The composition of the Interim Administration was agreed at the conference: Hamid Karzai was named chairman, and the rest of its members represented a carefully assembled mosaic of different ethnic and tribal leaders. Rubin observes that the Bonn Agreement reflected the distribution of political power at the time, which in turn was a result of the US strategy to oust the Taliban.Footnote 81 The composition of the Interim Administration was widely viewed as lopsided, at best. It had a high – critics would say too high – representation of Tajiks from the Northern Alliance in control of the most powerful ministries. The three key ministerial portfolios of Defense, Foreign Affairs, and the Interior were allocated to the three Panjshiri leaders who had served as Ahmed Shah Massoud's lieutenants – Mohammed Fahim, Abdullah Abdullah, and Yunus Qanooni, respectively.Footnote 82 Triumphant and resurgent warlords such as Ismail Khan and Rashid Dostum, who had participated in the fighting against the Taliban, regained control in their regions through their appointment to governorships. As is the fate of most losers in civil war, the Taliban stood no chance of being included in a power-sharing arrangement – but it remained a force with considerable support and organizational strength in the Pashtun-dominated southern parts of the country. In the Taliban home base of Kandahar province, the governorship was given to another warlord, the Pakistan-affiliated Gul Agha Shirzai. Independent militias continued to receive funding and weapons from coalition forces that sustained the fight against the Taliban instead of disbanding and becoming part of a new civil society. Some factions reignited old internecine conflicts quickly after the Bonn conference, vying for power and the control of territory and toll revenue.Footnote 83 On the other hand, no widespread threat to the security and stability of the country emerged immediately, nor any major challenge or threat to the Bonn process itself.

Elite Settlements in Comparative Perspective

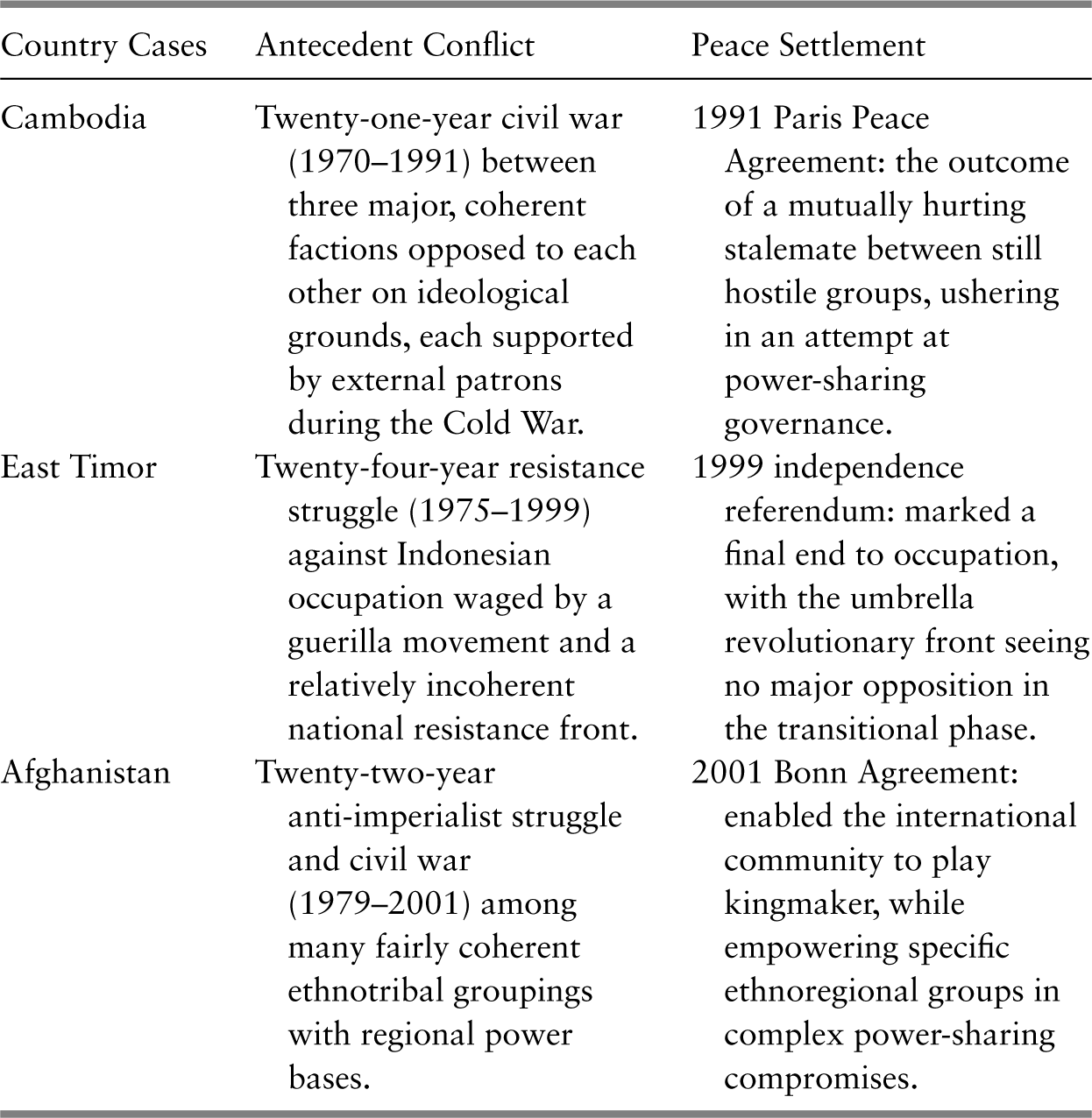

Although violent conflicts in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan were all sparked in some way by decolonization and Cold War politics and each lasted for just over two decades, this chapter has demonstrated that the three violent struggles had distinct motivations and features that are crucial to understanding the peacebuilding record that followed (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1 The Cambodian, East Timorese, and Afghan conflicts and settlements in comparative perspective

| Country Cases | Antecedent Conflict | Peace Settlement |

|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | Twenty-one-year civil war (1970–1991) between three major, coherent factions opposed to each other on ideological grounds, each supported by external patrons during the Cold War. | 1991 Paris Peace Agreement: the outcome of a mutually hurting stalemate between still hostile groups, ushering in an attempt at power-sharing governance. |

| East Timor | Twenty-four-year resistance struggle (1975–1999) against Indonesian occupation waged by a guerilla movement and a relatively incoherent national resistance front. | 1999 independence referendum: marked a final end to occupation, with the umbrella revolutionary front seeing no major opposition in the transitional phase. |

| Afghanistan | Twenty-two-year anti-imperialist struggle and civil war (1979–2001) among many fairly coherent ethnotribal groupings with regional power bases. | 2001 Bonn Agreement: enabled the international community to play kingmaker, while empowering specific ethnoregional groups in complex power-sharing compromises. |