Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Enslaving Masculinity: Rape Scripts and the Erotics of Power

- III India's Aryan Queen: Colonial Ambivalence and Race in the Mutiny

- IV Coherent Pasts in Hindi Literature and Film

- V Unmaking the Nationalist Archive: Gender and Dalit Historiography

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

II - Enslaving Masculinity: Rape Scripts and the Erotics of Power

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2014

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- I Introduction

- II Enslaving Masculinity: Rape Scripts and the Erotics of Power

- III India's Aryan Queen: Colonial Ambivalence and Race in the Mutiny

- IV Coherent Pasts in Hindi Literature and Film

- V Unmaking the Nationalist Archive: Gender and Dalit Historiography

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

In the British imagination, the ‘Mutiny’ never ended.

Kim A. WagnerIn ‘An Interesting Condition’ written for The Pioneer in 1888, Rudyard Kipling personified India as a licentious woman available to every intruder:

The East intrigued with Alexander. It was a liaison passenger.

With the Toorkh. It was an affaire militaire only…

With the Rajput; with the Hindu. It was to pass the time…

With the Portuguese. It was an aberration erratic.

With the Frenchman. It was an affair of the heart.

But she was a woman. The Englishman came…

The Englishman believes he has married her…

These things are the marks of the husband English. But…ask her. She has seen many lovers.

A woman who has seen many lovers will see more…

The poem imagines the country as a woman indiscriminate in her choice of lovers and unforgiving in her promiscuity. While the men are identified by geography or culture, the woman is adrift of such mooring and wholly given to sexual mobility. The British believe they have entered an honourable union, but the Englishman's confidence, buttressed by his naïveté, is betrayed. Whereas earlier narratives rehearsed European colonialism in heteronormative metaphors as the providential dominance of man over woman, thus Britain over India, a hundred years of colonial rule also exposed the anxiety and instability of such binaries. For Kipling, India was not a passive femininity, but rather an avaricious and perfidious sexual being – actively seeking the demise of the lover.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

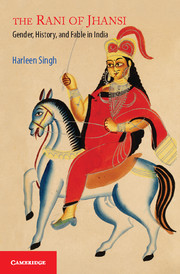

- The Rani of JhansiGender, History, and Fable in India, pp. 33 - 66Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014