Anatomy of Resentment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2021

Summary

As it stands now, Europe has lost its self-confidence, its energy and its hope that the next century will be the “European century”. From Beijing to Washington – and even in Brussels itself – the Old Continent is widely viewed as a spent geopolitical force, as a great place to live but not a great place to dream. These days the European Union is less a declining power than a “retired power” – wise but inactive, prosperous but elastically accommodating. The perversity of the situation is that the European model has fallen victim not to its failure but to its success. The shock that Europeans experience today recalls the shock of the Japanese technology companies of a decade ago when they suddenly realised that although they manufactured the world's most advanced cell phones, they could not sell them abroad. Consumers elsewhere simply weren't ready, since Japanese devices relied on advanced technologies, such as third-generation e-commerce platforms, that were not widely used in other countries. Japanese cell phones, in other words, were too perfect to succeed.

Some dubbed this phenomenon Japan's “Galápagos syndrome”, referring to Charles Darwin's observation that animals living in the remote Galápagos Islands, with their unique flora and fauna, had developed special characteristics not replicable elsewhere. Much the same could be said of today's Europe, which evolved in an ecosystem shielded from the wider world's rougher realities – and has consequently become too advanced and too particular for others to follow. So, is Europe's attractiveness rooted in the universal appeal of its culture and institutions or in its unique nature? The current refugee crisis in Europe suggests an interesting answer to this question.

A decade ago, the Hungarian philosopher and former dissident Gaspar Miklos Tamas observed that the Enlightenment, in which the idea of the European Union is intellectually rooted, demands universal citizenship. But universal citizenship requires one of two things to happen: Either poor and dysfunctional countries become places in which it is worthwhile to become a citizen, or Europe opens its borders to everybody. Not one of these two is going to happen soon, if ever. Today the world is populated by many failed states nobody wants to be a citizen of and Europe neither has the capacity to keep its borders open nor will its citizens-voters ever allow it.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

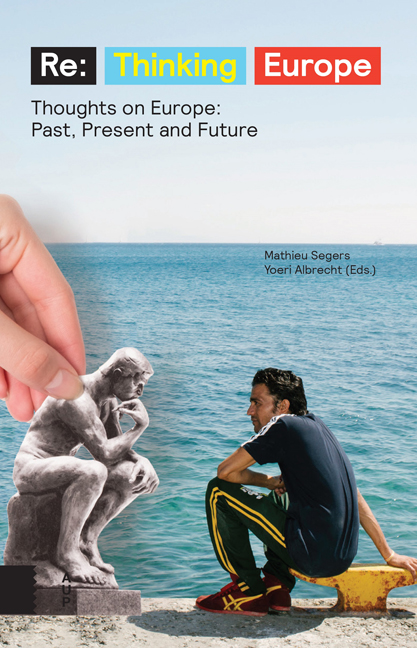

- ReThinking Europe Thoughts on Europe: Past, Present and Future, pp. 109 - 120Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2016