Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2019

Summary

DURING HILLARY CLINTON'S historical run for the presidency in 2016, anybody with even a remote interest in politics was bombarded with brutally sexist and misogynist messages and images. There was the “I Wish Hillary Had Married O.J.” bumper sticker, a commercial item that appeared in 2008. In response to her campaign for the Democratic Party nomination, which she lost to Barack Obama, there was the Hillary Clinton nutcracker tchotchke and Rush Limbaugh's rhetorical question “Will this country want to actually watch a woman get older before their eyes on a daily basis?”1 More recently, we witnessed the T-shirt that cast Trump as Perseus holding the head of the decapitated Hillary-Medusa, and the popularization of the phrase “nasty woman.” While such sexism assumed a particularly virulent and violent character in the 2016 US election, it is by no means a strictly American affair, nor is it a new phenomenon. Rather, Western civilization is deeply marked by a long history of misogynist prejudices against women in positions of power. Aristophanes broached the theme of gender-based power and subversion with Lysistrata (411 BCE), in which female characters deploy the most important weapon, presumably, in their arsenal: withholding sex to stop a war. Similarly, Thesmorphoriazusae (411 BCE) expands Aristophanic comedy's repertoire, with female characters organizing to seek vengeance against contemporary male poets for their distorting representations of women. One of the comedies in the classical canon, his Assemblywomen (391 BCE) derives its humor from the outlandish notion that women might run the government. It is noteworthy that women who take control of their government, their bodies, and their reputations, mediated by the male imagination, provide the stuff of comedy.

While the classical canon is imbued with gender prejudice, there are counter narratives. The defender of her sex against the surge in misogynist literature in the fifteenth century, Christine de Pizan (1365–1431), modeled a mode of leadership and community; Pizan also wrote a principled defense of women. In the medieval European context, a war of words and deeds ensued, the querelles des femmes. The English translation of her Le livre de la cité des dames (1404) appeared in 1531, more than a century after Pizan's death and two decades before Mary I (Bloody Mary) and Elizabeth I wielded real power in England.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

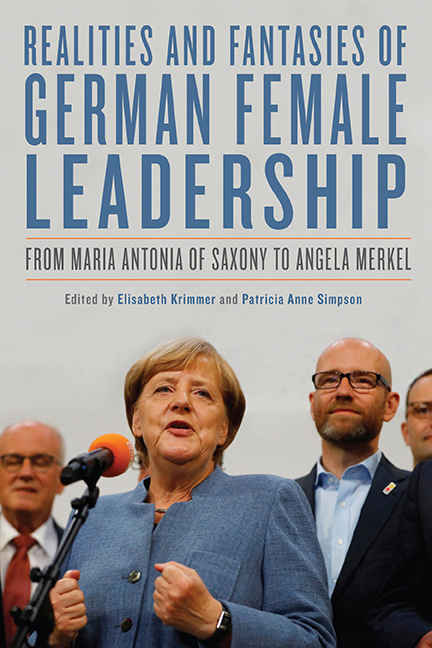

- Realities and Fantasies of German Female LeadershipFrom Maria Antonia of Saxony to Angela Merkel, pp. 1 - 24Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019