8 Breakdown and barbarians

Introduction

Rather in the way that the last two chapters formed a diptych, concerning themselves with different but complementary aspects of the production, mobilisation and deployment of surpluses in the late Roman world, this chapter and the succeeding one will form a diptych relating to defining features of the fifth century and its archaeology. This chapter will concern itself essentially with the breakdown of the structures of imperial political, military and fiscal control in the West, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the appearance of features of the archaeology which may (or may not) be related to the increasing presence and importance of ‘barbarians’ on the territories of the Western Empire. The following chapter will examine the consequence of these developments for wider economic and cultural formations across the West, which ran to a somewhat different tempo.

The archaeology of the fifth century on its own would tell us that there were major changes across the board in the Western provinces in this period; it sees massive alterations over a short timescale. Archaeologically, the fifth century marks an important threshold of development, one that sees important structural changes across the range of the evidence, thus marking a far more important horizon than the ‘crisis’ of the third century. Yet, like the third century, the fifth century was also a crisis, in the technical sense that it was a point at which the ‘patient’ recovered from or succumbed to the ills besetting it; in this case the universal perception is that it succumbed to a virulent attack of barbarians. This is, of course, a view derived from the textual sources, from their narratives, often with a strong moralising agenda, of military, political and administrative collapse and the replacement of the imperial system by the Germanic successor states of the early Middle Ages. In this chapter the traditional discourse of the ‘fall of the Western Roman Empire’ will not be ignored (it hardly can be), but it will be viewed from a different perspective, that of the archaeology, which may give us a rather different range, chronology and causation of events, in particular as regards the place of the various brands of barbarian peoples.

Chronological outline

The traditional narrative and structure for understanding the events of the fifth century has been derived from the historical and other textual sources (for a representative, recent and detailed treatment, see Heather Reference Heather2005 and references). A much abbreviated version of events in the first half of the century is presented here to give a chronology and an outline of events in the short term. It must be emphasised that this is not because this narrative is ‘true’, and still less because the archaeology is simply there to ornament this narrative. It is because the narrative and the events it relates have given both the accepted chronological structure to the fifth century and a version of events. This chronology and these events have for a long time shaped the presentation and the discussion of the archaeological evidence, so that it is necessary to have an appreciation of the traditional narrative, even if the intention is to discard it and replace it with something else more responsive to the nature of the archaeological evidence and its significance(s).

On the last day of what is normally given as the year 406, in fact very probably 405 (Kulikowski Reference Kulikowski2000), large barbarian forces consisting of Alamanni, Alans, Sueves, Vandals and others crossed the frozen Rhine in the region of Mainz and penetrated deep into Gaul, encountering little opposition from imperial forces and heralding fifteen years of war and instability. This provoked the usurpation in Britain of Constantine III, who crossed to Gaul to try to restore order and to deny to the barbarians the passes into Spain. In both of these he was unsuccessful, surrendering to imperial forces at Arles in 411 and being done away with. But by this time the Alans, Sueves and Vandals had penetrated into Spain, where the Sueves carved out for themselves a territory in the north-west of the peninsula. The imperial authorities, under the direction of the very able patrician Constantius (later briefly emperor in 421), manipulated the Visigoths, fresh from their part in the sack of Rome in 410, into south-western Gaul and then into north-eastern Spain to try to defeat the other tribes, before eventually settling them in south-western Gaul in 418, or more probably 419, ceding them rights from Toulouse to the Atlantic. The Visigoths were intervening under Roman auspices in Spain from 422, but a more worrying presage of things to come saw them attacking the imperial seat in Gaul, Arles, as early as 425. In 429, the Vandals and many Alans crossed to north Africa, where they took Carthage in 439, depriving the Western emperors of their richest tax lands. In 433, military command of the West was conferred on Aetius, who tried to stabilise the position by force, defeating the Burgundians and resettling them around Geneva and westwards in 436/7, defeating the Bacaudae (Drinkwater Reference Drinkwater1992) (a local uprising) in Armorica (Brittany) in 437, and in 439 attempting to subdue the Visigoths, who had been attacking Arles and Narbonne, an attempt that was unsuccessful under the walls of Toulouse but at least led to a reaffirmation of the original treaty of 419. The relatively peaceful 440s saw the various contestants with claims over territory in the West circling and manoeuvring; the imperial government under Valentinian III (425–55), represented in Gaul by Aetius, was contesting with the other factions also, the Visigoths, Alans (resettled by Aetius on the Loire in 442), Burgundians in central and southern Gaul, and the nascent Frankish power in the north. In Spain the remnants of the imperial authorities maintained a precarious hold on the Mediterranean littoral and adjacent inland areas, with the Sueves becoming more dominant in the north-west and expanding their territories. In 451 in Gaul, the contending parties sank their differences and united under the leadership of Aetius to face the invasion of Attila and the Huns, successfully facing them down at the battle of the Catalaunian Plains (near Troyes in central Gaul), a battle in which Theodoric I, king of the Visigoths, was killed. Aetius was to meet the fate of several successful late Roman generals by being assassinated, in this case by Valentinian III personally, in 454, Valentinian himself being assassinated in revenge the following year, all of this testament to the poisonous faction fighting on the Roman side, which could affect relations with the Germanic rulers.

As can be seen, two intertwined themes are central to this narrative: the increasing enfeeblement of the unified imperial power in the West and, as both cause and consequence, its lands and power being taken over by a series of kingdoms ruled by dynasties claiming Germanic descent and identity. To turn from this short-term ‘kings and battles’ history to how this all intersected with more medium-term processes, what we need to consider is how the military and political events acted upon the existing structures of the West, and, in particular, how they brought about ‘The end of the Western Roman Empire’. Of course, what is generally meant by this expression is the end of imperial political, administrative and fiscal control, the end of the late Roman state and its structures, and it is that which we shall examine now. What happened to the populations of the West and their political, economic and cultural formations will be the concern of the next chapter. The process of the dissolution of the Roman state control over the territories and peoples of the West and its proximate causes can be fairly readily characterised and understood. As has been stated earlier (p. 19), the political, administrative and fiscal systems of the late Roman Empire depended in the last analysis on the army. It was the army that was there to hold the frontiers against external threat and sought to guarantee internal peace and stability. It underpinned emperors and their reigns over their peoples (or, alternatively, attempted to replace them), and it also underpinned the state’s fiscal system; after all, it was the principal beneficiary of that very system. In order to do this, it had to have ensured sources of manpower, money and materiel. In the fourth century this balance held and the army maintained its manpower (though with increasing difficulty) and was paid and supplied, though, as we shall see, the 390s may well have marked a turning point for the Western armies. But certainly from 406, the Western Empire started to suffer not only military defeat but also, in crucial distinction to the ‘third-century crisis’, permanent, large-scale loss of territory. With territory went recruiting-grounds, taxpayers and resources, enfeebling the army and the state. The incoming Germanic peoples picked up on this weakness and sought to turn it to their advantage by taking further imperial territory. Increasing loss of territory translated into decreasing Roman ability to do anything to restore the situation, a vicious cycle, and by the 450s the once-mighty Western Empire was but one player among many in the campaigns and alliances. By the end of the 470s, it was not even that: military debilitation had resulted in political oblivion. This was the structural crisis of the Western Empire, one from which it did not pull through. Of course, this was not planned or predestined, either by the Romans or by the Germanic peoples. On the Roman side, such things as the settlement of the Visigoths in Aquitaine in 419 were doubtless seen as expedient and temporary – it got the Roman authorities off a particular hook. They could not know at the time that an allocation of land would turn into an independent kingdom. Nor, so far as we can tell from the Roman textual sources, was there any intention on the Germanic side to destroy the empire as such; rather, they wanted to establish their claim to parts of it. If in this process they had to ally themselves with or confront the imperial government, well, that was politics. One could say that the Western Roman Empire was one of the larger of history’s victims of the law of unintended consequences.

The end of the Roman army in the West

Central to the existence of the Roman Empire was its army, which defended imperial territory, safeguarded the person of the emperor and ultimately underpinned the judicial and fiscal systems that sustained the emperor and the empire, and, indeed, the army. Its progressive debilitation and ultimate disappearance are therefore equally central to the study of the fate of the Western Empire, since it can be said that without a Roman army there could be no Roman Empire. The fate of the Roman army in the West and the processes by which it disappeared are difficult to pin down, particularly from the archaeological evidence; nevertheless, the attempt must be made, even if only to demonstrate the problems inherent in the exercise.

In Chapter 2 it was argued that the crucial distinguishing feature of the late Roman army was that it was a standing army, paid, housed, equipped and supplied by the state (the taxpayer), and commanded by officers appointed ultimately by and answerable to the emperor as part of the ‘public’ power of the state. It was a major institution of the Roman state, organised into functional types (comitatenses were the internal field armies, limitanei/ripenses the frontier armies) and into regional commands. Each command (as listed in the Notitia Dignitatum) consisted of a variable number of named units, units that had a long-term existence as organisations independent of the command of which they might form a part or of the soldiers or commanding officers who at any one time made them up (for instance, unit titles listed in northern Britain can be traced back some three hundred years before their appearance in the Notitia). The soldiers were defined by the state authorities through formal processes of recruitment, training, registering in and membership of units; subordination to officers and regional commanders; and receipt of pay, provisions and equipment. This ‘etic’ (external) definition overlapped with the ‘emic’ (internalised) self-definition of the soldiers inculcated and routinised daily through the forts in which they lived, the clothes they wore, the weaponry and armour they used, the oaths they took, the ceremonies they attended, the distinctive military language and laws they used, the unit to which they belonged and its esprit de corps, and their consciousness of membership of the wider ‘imagined community’ of the soldiery, set apart from the wider civilian population of the empire. This definition of the late Roman army has been recapped here, because, central to the argument that follows about how to model archaeologically the demise of this institution, will be precisely the fact that it was a distinctive institution, in particular one that was sustained by the state and was part of the ‘public’ power structures of the state. It will be proposed that crucial for our understanding of what happened to the army in the fifth century will be the idea that it progressively ceased to be sustained by the ever more enfeebled state, and that, as a result and in its place, there came about command over, and expressions of, military power that increasingly were the responsibility of individual commanders rather than the imperial command and control structures: military power increasingly became ‘privatised’.

A key site which we may use as a case study because of its large suite of excavated evidence covering these years is the fort of Krefeld-Gellep (Gelduba) on the lower Rhine (cf. Figure 2.2), more particularly the cemeteries excavated between 1960 and 2000 under the direction of Renate Pirling (for a summary to 1985, see Pirling Reference Pirling1986; for the more recent work, see Pirling et al. Reference Pirling, Siepen, Noeske-Winter and Tegtmeier2000 with bibliography). The majority of the fourth-century inhumation graves exhibited the relatively simple Roman provincial burial rite common across northern Gaul and the Rhineland or Britain (cf. Chapter 2, p. 51) and contained a range of grave goods, most often pottery. Some male graves contained items of dress such as belt suites and crossbow brooches, suggesting that the dead may have been soldiers of the garrison at Krefeld. But the presence in one grave (Gr. 4755) not only of an elaborate, later fourth-century belt suite of Roman manufacture but also a bronze neck ring of a type originating east of the Rhine suggests contact with that area, though this supports the concept of a Mischzivilization with cultural traits borrowed from either side of the river. Likewise, in some female graves of the later fourth century, there were pairs of brooches, including Tutulusfibeln, with both the objects and the way of wearing them reflecting material and practice from east of the Rhine. Here was also one female grave, Gr. 4607, containing a mirror of a type common in the area known to the Romans as Sarmatia. Does this echo the Sarmatae gentiles of the Notitia (cf. Chapter 2, p. 92), or was it just a trinket? At Krefeld there was also metalwork indicative of contacts with Pannonia and some glazed pottery vessels, more common in Pannonia than the Rhineland (Swift Reference Swift2000b: 79–82). The interpretative problem is whether the areas of origin of the objects reflect also and directly the areas of origin of the persons with whom they were buried, in which case they may be used as ‘ethnic’ markers, telling us something about the origins of the garrison of fourth-century Krefeld. Alternatively, of course, the objects may have reached Krefeld and been buried there by means which divorced them from their ‘ethnic’ significance. To complicate matters, Gr. 3007 contained bracelets both of Danubian and of British origin (Swift Reference Swift2000a: 176, Reference Swift2010), demonstrating the difficulties inherent in using objects rather than attributes such as burial rite (or eventually chemical and physical analyses) to determine geographical, let alone ethnic, origins. This was all in the fourth century when the site was a fort, normally thought to have housed a garrison of the regular, standing Roman army: it is a testament to a mix of material culture at one site associated with the late Roman army and thus to the heterogeneity of the personnel of that army.

From the turn of the fourth and fifth centuries, both burial rites and objects start to change, with the first appearance of graves containing weaponry and handmade ceramics of non-Roman origin (e.g. Gr. 2650), though this in itself says nothing about the origins and loyalties of the troops or warriors at Krefeld. But from about the end of the first quarter of the fifth century, we begin to see weapon burials with long swords (spathae), spearheads and knives, along with brooches and buckles of ‘Germanic’ (in the sense of origins east of the Rhine) type. At the same time there are female burials with mainly ‘Germanic’ brooch types and other dress elements. Both male and female burials had glass vessels (including cruder ones of forest glass, compared with the technically superior tradition of the Roman-derived products), but also pottery that was increasingly of ‘Germanic’ forms and handmade. These burials, though in the same cemeteries as the fourth-century ones, tended to cluster in groups. The excavators interpret these changes during the first half of the fifth century, taken together, as representing the arrival of families or kin groups from east of the Rhine, led by male warriors and in some sense supplanting the regular, Roman garrison of the previous century. In the excavators’ opinion these were Franks. While not necessarily accepting such a precise ethnic identification (we shall examine the problems of the archaeology of ‘fifth-century Franks’ below), we can at the very least argue on the basis of the material culture and maybe features of the burial rite (e.g. deposition of weapons) that these burials express much closer links with the material culture and status and gender markers of peoples to the east of the Rhine. Again, in default of physical or chemical analyses, we cannot be certain, but there is a plausible case to be made that these changes represent people as well as objects from east of the Rhine. Given that Roman provincial pottery was still available, and used in some of the burials, the presence of handmade pottery of ‘Germanic’ type would seem to be a persuasive factor in favour of the people, as well as the pottery, being of Germanic origin, especially given the importance of pottery in the burial rites of the Germanic peoples at the time.

What cannot be established from their funerary rites is whether the menfolk buried at Krefeld in the fifth century were, by either ‘etic’ or ‘emic’ definition, ‘Roman soldiers’. Was there a continuing Roman state or government that regarded the men of Krefeld as subject to its control, loyal to the emperor and due some sort of payment or support in exchange? Or were they subordinate to some form of officer who still regarded himself as loyal to the emperor, even if the emperor and his bureaucracy may not have been aware of the existence of either the men or their officers, and thus could be thought of as ‘Roman’ in that sense. Did they regard themselves as in any sense ‘Roman’ soldiers, loyal to the emperor and part of a wider community of the Roman soldiery? Or was their allegiance to an ethnic leader whose loyalties lay to himself and his followers, making it very hard to see Krefeld any longer as a ‘Roman’ military installation with a ‘Roman’ garrison and commander? To date, the Krefeld-Gellep cemeteries provide us with by far the fullest evidence in the West for developments through the second half of the fourth and the first half of the fifth centuries. What this example shows is that, whereas it is possible to demonstrate continued occupation at a site that in the fourth century was a Roman military installation, after the beginning of the fifth century it becomes progressively more difficult to reconstruct from the archaeology what the function and status of these groupings may have been, or their relation (if any) with what remained of the Roman state.

A comparable site, this time on the upper Rhine, is Kaiseraugst (Drack and Fellmann Reference Drack and Fellmann1988: 300–12, 411–14). Within the fortification, there was probably a principia, and certainly, and unusually, a major bathhouse, a storehouse and a church. From within the fortification came the major, mid-fourth-century Kaiseraugst treasure (Cahn and Kaufmann-Heinemann Reference Cahn and Kaufmann-Heinemann1984). Some 300 m south-east of the fortress lay a cemetery, of which some 2,000 burials have been excavated and which shows a similar sequence to Krefeld-Gellep. The burials of the second half of the fourth century either had no grave goods or were furnished with pottery and, in a few cases, items of dress, in the standard late Roman way. From the end of the fourth century began to appear burials with ‘Germanic’ grave goods, though, at the same time, there was built a small apsidal structure, quite probably a cella memoriae, so religious change is as evident in this cemetery as any ethnic change there may have been. The cemetery was to remain in use until the seventh century, by which time it held gravestones with Germanic names. But again, for the fifth century, the ethnic identities and the political loyalties of the changing population remain unfathomable, as also their relationship to the Roman state. On the middle Rhine, one may point to sites such as Alzey and to a lesser extent Altrip. The fort at Alzey (Oldenstein Reference Oldenstein1986) had been established under Valentinian I; it was square in shape with projecting towers, and the internal accommodation took the form of buildings along the inside face of the walls, leaving the centre of the enclosure largely free of buildings (Figure 8.1). The fort seems to have been partially destroyed around 400; this was ascribed to the Germanic invasion in 406. Thereafter, the damaged buildings were restored or replaced. The material culture associated with this phase is of types much more closely linked with that from east of the Rhine, and is interpreted by the excavator as the installation of a Germanic garrison, possibly of Burgundians, but still under Roman command. Alzey was destroyed by fire in the middle of the fifth century.

A common feature of the archaeological sequences at these forts and in their cemeteries is the increase in the amount of ‘Germanic’ material from them after the start of the fifth century. In some of the cemeteries, this material comes from what seem to be male and female graves in restricted areas of burial, and this may well point to family groupings. Both here and in Chapter 2, there has been an insistence that any simple equation between an object and a specific identity or ethnicity, or between the presence of an object in a burial and the identity or ethnicity of the occupant of the grave, should be avoided. These arguments stand. But at the case-study sites and at many others with more partial documentation, what changes in the fifth century is the volume and range of this new material and its increasing dominance of the material culture record, either on its own or in combination with the latest types of Roman-derived material culture, especially belt fittings. Whereas at the level of the individual object or the individual occupation deposit or burial it is possible and desirable to be cautious about ethnic ascriptions, what is different in the fifth century is the aggregate level of these types of material culture, which form a significant proportion of the total by the end of the first half of the century and pretty much the total by the end of the century. The origins of this material culture lay ultimately east of the Rhine and north of the Danube, the ‘Pontico-Danubian’ area, the homelands of the Germanic peoples and of other non-Germanic peoples. It may be objected that this is simply to accept the agenda of Roman writers and their ethnic labelling, but the archaeology makes it abundantly clear that there was in the fourth century and on into the fifth a series of distributions of related material culture across these areas (e.g. the complex often referred to as the ‘Elbegermanen’ [see Drinkwater Reference Drinkwater2007: Ch. 2; Drinkwater and Elton Reference Drinkwater and Elton1992]) that differentiated these peoples from those in lands directly subject to Roman imperial power. It becomes increasingly hard to sustain the interpretation of the large-scale arrival of this material culture at a large number of Roman military sites all along the Rhineland simply in terms of a continuing Roman provincial garrison and/or population as helpless fashion victims with a taste for Germanic goods. The presence of what may well be discrete groupings in the cemeteries with this sort of material, as against the continuing Roman provincial rites, as at Krefeld-Gellep, does look very much like the movement of people, not just of pots or brooches. This, of course, could have coexisted with the indigenous populations starting to redefine their identities and ethnicities in terms of the Germanic incomers, particularly given that these latter may have had a privileged position, one dependent on the martial prowess of the menfolk. So ethnic ascription from material culture remains problematic, and not all burials with ‘Germanic’ material need have been the burials of Germans from across the Rhine. Indeed, what these burials seem to show is the progressive ‘Germanisation’ of the groupings (incomers or indigenous) in aspects of their funerary practice such as, in particular, the preparation of the corpse and, in the case of women, above all by laying-out bodies in forms of clothing which, even if not making claims to specific ethnic identities, were certainly making claims not to follow Roman provincial practices. The increasing presence of triangular ‘Germanic’ combs may suggest the importance of hairstyles alongside the more obvious clothing, suggesting that a situation developed where markers of ethnicity (or at least of not becoming Roman) became more important, particularly at burial, than markers of relation to the Roman state and its army.

So, by the mid fifth century, it would seem that the peoples living and buried at a series of Rhineland forts increasingly used material culture of non-Roman origins, mainly from areas that Roman written sources classed as ‘German’. Whether all these people were from those areas to the east of the Rhine and to the north of the Danube remains unknowable; it may be that some of them were from west of the Rhine but assimilated to this ‘Germanic’ identity (these matters are discussed more extensively later in the chapter). But the question posed in this section of the chapter is that of the processes by which the Western Roman army ceased to exist, or at least to be recognisable in the archaeology. Earlier it was argued that a ‘Roman’ army fulfilled certain ‘emic’ and ‘etic’ definitions as regards the internalised loyalties and practices of the soldiers, the institutional existence of the army and its units, and the political loyalty of the army to the emperor. The changes in the archaeology, particularly the material culture, suggest that during the fifth century the ‘emic’ definitions of the people at these sites moved away from that which had characterised the garrisons of the fourth century towards something which to Roman eyes would appear more ‘barbarian’. But ‘barbarians’ served in the army of the fourth century at all levels, as was seen in Chapter 2, so that in itself is not a sufficient index of no longer regarding themselves as servants of the emperor, or being so regarded by others. What the archaeology at present cannot tell us is where the sense of the community to which individuals belonged lay or where their political loyalties lay. Did they regard themselves as soldiers of the emperor, or did they regard themselves as members of ‘tribal’ or other groupings and followers of individual leaders whose loyalties were negotiable? There is, though, one class of material which may be a strong indicator of an ‘etic’ definition – a definition made by the Roman authorities – and that is the coinage, which was closely tied to the question of army pay and loyalty.

Coinage in the early fifth century

In the previous chapter the striking of coinages by the late Roman state was explicitly tied to the political economy, specifically the payment/clawback system put in place by which precious metal was paid out to discharge the obligations of the state, above all to pay the army, and then recovered through a variety of means including the compulsory changing of gold and silver for base metal by the nummularii. In the West the bulk of state commitments was to the army, to its infrastructure, such as the fabricae, and to the bureaucracy, so this payment/clawback nexus was very closely allied to the army. At the turn of the fourth and fifth centuries, there were major, far-reaching changes to the state production of coinage, a horizon which perhaps has not received due attention (cf. Kent Reference Kent1994). The precious metal coinage had therefore always been central to the state’s meeting its obligations, especially as regarded the payment of the army. Silver coins, principally the siliqua, had been struck at the Western mints, mainly Trier but also Lyon and Arles, through the second half of the fourth century. At the turn of the fourth and fifth centuries, these mints ceased precious metal production, and henceforth the Western authorities struck gold (in small quantities) and more especially silver, principally at Milan. The usurper Eugenius struck a considerable silver coinage there in 393–4, but after his suppression at the battle of the Frigidus in early 395, there was an hiatus in production until 397. The five years between 397 and 402 saw a huge issue from Milan (rev. Virtus Romanorum). Thereafter the principal mint for precious metals in the West was Ravenna, particularly between 408 and 425, with sporadic production at Rome and Aquileia in 407–8 (cf. Guest Reference Guest2005a: 74–6). But these later issues did not penetrate north of the Alps in any quantity. The usurper Constantine III (406–11) did strike in silver, as well as some gold, at mints such as Lyon, both before and after the death of Arcadius in 408, but not in large enough quantities or for long enough to reverse the overall trend. For the coinages in base metal, in the year 395 the Western monetae publicae, the mints supplying these coins, were reorganised, massively changing the scale and nature of the coinage produced and supplied. Trier, Lyon and Arles largely ceased to strike in base metals; in the West, only Rome continued to do so in any volume. This step change was succeeded by another in 402 when the three Gallic mints effectively ceased base metal production at the end of the Victoria Auggg issue in 402, and the succeeding Salus Reipublicae, Urbs Roma Felix and Gloria Romanorum (three emperors) issues of Rome hardly circulated north of the Alps.

So from about 402 the Western Empire was suddenly in a situation where it was no longer producing the coinages, particularly silver and base metal, that had been vital to its revenue and expenditure cycle, the expenditure, of course, directed principally at the army. It is important to recognise that this was developing before the failure of the Rhine frontier and the start of the barbarian land grabs from the end of 405 on, so it cannot be, in origin at least, an effect of these. Also, Italy seems to have been different, since silver was still struck at Ravenna, and bronze continued to be struck at and circulated from the Rome mint. One possible explanation is that 402 marked one of the pauses in the production of coin which are detectable in the fourth century, the intention having been to resume coining, but this never came about outside Italy because of the events of 406 and the following years when a combination of barbarian incursion and the usurpation by Constantine III meant no coins of the later issues would be supplied to such unstable areas. It is noticeable, though, that even after the suppression of Constantine III in 411 and the re-establishment of a measure of imperial political and military control north of the Alps, the large-scale supply of coin to those areas was not resumed. In that case the imperial authorities presumably had to find other means of paying those soldiers and units still loyal to them. A logical, if extreme, response would have been the Western authorities deciding that they no longer needed to support these armies, but this would fly in the face of the fundamental importance of the army in maintaining the empire and the imperial system; it also ignores the textual evidence for something called a West Roman army in the first half of the fifth century. But, less controversially, one might propose that the state had chosen, or had been forced through circumstance, to change the ways in which it sustained and remunerated its armies. The fiscal system, insofar as it related to the armies, was designed in part to produce the wherewithal to pay them, but also the revenues to cover the costs of heads of expenditure such as the construction of military installations, the provision of weapons and equipment (through the fabricae), and the ensuring of foodstuffs and other supplies over and above those directly raised from and transported by the taxpayer. Interestingly, the trend over the latter part of the fourth century had increasingly been to adaerate these obligations – that is, to commute them for coin/bullion payments. If the Western Empire now no longer wished to raise the precious metals necessary for discharging these functions, then, presumably, the armies were to be supported in some other way(s), perhaps by more direct requisitions from the provincial populations, though we have no positive evidence for this. Logically, this would also entail the dismantling of the necessary bureaucracies under the comes sacrarum largitionum (precious metal revenues and payments), the magister officiorum (the fabricae) and the praetorian prefect of the Gauls (billon coinage and materiel). In fact, it is hard to trace these officers, save the praetorian prefect, in the written sources outside Italy much after the start of the fifth century. This picture of what may have happened to the Western armies from the end of the fourth century is provisional and needs more work and thought on the precise chronology of these changes and on the distributions of the various coin issues. But the major changes to the supply and circulation of coinage and the significance of those changes do have to be recognised and pursued. Either it was intended to be a temporary pause, one that was overtaken by events, or it marks a purposive shift in the imperial fiscal system beyond the Alps. Whichever it was, the result was that from the start of the fifth century the Western authorities could not or would not be in a position to maintain a standing Roman army of the traditional form. Some other expedients would have to be resorted to.

The archaeological evidence from military installations suggests that increasingly they were occupied by soldiers or warriors of ‘Germanic’ origin or by locals who were increasingly defining themselves in non-Roman ways. It could be proposed that this is the horizon at which the control of force passes out of the hands of the Romans and into those of the incomers as the latter supplanted the Roman army in what had been its garrison forts – a power and land grab. But the relationship of Roman provincial and Germanic material cultures and burials suggests rather that the two coexisted, at least in the first half of the fifth century. In this case one might propose a scenario whereby instead of a standing army with soldiers whose recruitment, routines of life, identity and ideological commitments were shaped by the Roman army and state, military force in the West was increasingly committed to ‘barbarian’ groupings for whose support the state did not have to take responsibility in the same way as it had for a ‘Roman’ army. In effect, it was an extension of the principle and practice of foederati, tribal detachments who fought for Rome but were not part of her standing armies. Presumably, the Roman state settled them in its forts and allocated them provincial land off which to support themselves on the understanding that they would fight for the emperor under the command of the senior officers (comites rei militaris and the like), who were, as we can see from the texts, still appointed to Gaul and Germany and to a lesser extent to Spain. This would echo the arrangements that we know were made for the settling and support of the Visigothic army and people in south-western Gaul in 419 (see below). Under this scenario the Western authorities would no longer have needed to mint much in the way of coin for the areas outside Italy (and North Africa), and that is precisely what we see.

The progressive loss of the recruiting grounds and the tax base of Germany, Gaul, Britain and Spain from 406 forced the imperial authorities to desperate measures, measures that for the first half of the fifth century seem to have had some success, to judge by the textual accounts of senior Roman generals, such as Constantius and Aetius, in managing to some extent to resist, control and resettle the incoming peoples (cf. p. 359), above all in Gaul, down to the middle of the fifth century. What the texts also show is the increasing importance of the personal charisma and military competence of these generals in persuading an increasingly heterogeneous range of troops and warriors to follow them. The public power of the Roman state was increasingly being supplanted by loyalty to a leader. This is the appearance of the type of retinue of warriors known to the sources as bucellarii (hard-tack men), men who followed a successful military leader because he fed them and his successes yielded booty. After that, the textual sources show the increasing fragmentation of Roman power, or at least the power of those commanders who legitimised themselves by use of the name and aura of Rome, in both northern and southern Gaul (Spain seems by then to have been a lost cause), with the newly emerging barbarian kingdoms (see below) taking over as the possessors of military force. The rulers of these kingdoms, and presumably the leaders of smaller war bands elsewhere in Gaul, were, of course, another expression of this ‘privatisation’ of military force as they jockeyed with each other and the last of the ‘Roman’ commanders for control of people and resources. How different would fifth-century, nominally imperial troops have looked from Germanic warriors of the same period, especially since Germanic troops and units had formed part of the regular Roman army since the fourth century? Were such identities fixed and immutable? The evidence strongly suggests not; individuals and units could segue from one identity to another within an essentially unchanged material culture. For the mixed garrisons of the forts of the Rhine frontier and the interior of the north of Gaul, it was but a short step in the later fifth century to incorporating themselves into the locally dominant ethnic grouping – Franks, Alamanni or whatever. A distant echo of such a process may be the tale related by Procopius (Bellum Gothicum V.12.13–19) of how the last Roman troops on the lower Rhine assimilated themselves to the Franks while keeping their unit identities.

Barbarians and breakdown

The part played by the transformation of late Roman military formations and garrisons in the creation of the successor peoples to the Western Empire in the course of the fifth century will now form part of a wider discussion of the archaeological evidence for the settlement in Roman territory of the various Germanic peoples in the course of the fifth century. Before we embark on a consideration of the archaeology, the current state of the debate on using evidence from historical sources to ascribe to aspects of the archaeology, above all burials and the objects from them, a particular ‘barbarian’ identity (Alan, Frank, Vandal, Visigoth, etc.) needs to be outlined. In dealing with the archaeology, rather than try to encompass all the peoples mentioned in the historical sources and all the evidence that has been used, a work which would run to several volumes, we will use the technique of case studies to open up the subject and indicate the range of evidence types and possibilities of interpretation. These case studies will be the Visigoths for the south of Gaul and the Iberian peninsula, and the Franks for the north and centre of Gaul. Other peoples such as Burgundians, Sueves and Vandals will be mentioned as and where appropriate and to give a brief indication of modern studies. First of all, the term that will be most frequently used below to denote these incomers is ‘ethnic’ with its correlates such as ‘ethnicity’. This is currently the standard academic terminology, one that avoids other contentious terms such as ‘tribe’, ‘people’, ‘Volk’, ‘Stamme’ and so on, let alone the loaded concept, ‘race’, terms that lack precision in modern anthropological and ethnographic literature while at the same time giving the impression of a range of different sizes of population groupings in some sort of hierarchical organisation. ‘Ethnic’ and its correlates are used here simply to signify groups of people who were felt at the time or are considered now to be distinguishable from each other not on grounds of age, gender, status or religion but on grounds of having a matrix of attitudes and behaviours that set them apart from other neighbouring groups, and in particular set them apart from the Roman provincial cultures, which thus form a sort of ‘background noise’ against which the different ethnic groups stand out. In the cases we shall be looking at, these are also groupings that were mobile and thus ended up in areas to which they were ‘foreign’ in many senses of the word.

Over the last hundred years and more, the question of ethnic identity, what constitutes it and how it is expressed, has been the subject of intense debate, now conveniently and very accessibly summarised in Halsall Reference Halsall2007: Ch. 2. In the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such identity was held to be ‘primordial’ or ‘essential’ – that is, innate and, indeed, genetic (to be anachronistic) – and expressed through such things as belief in a common descent, a common kingship and nobility, a common religion, a common language, common customs and a ‘national dress’. An important feature of ‘primordial’ ethnic identity was not only that it defined the in-group but that it also defined (usually as inferior) out-groups. There was thus a strong belief in the works of early twentieth-century scholars such as Kossinna in the purity of each racial grouping and that they did not mix with other groupings; thus Alans did not mix with Vandals, for instance, let alone ‘Germans’ with provincial Romans, the latter view supported by many of the law codes issued by the successor kingdoms which distinguished strongly between ‘German’ and Roman provincial to the extent of forbidding intermarriage. Where such ideas about the ‘essential’ nature of ethnic identity and the need to maintain the ‘purity’ of the stock could lead was made catastrophically clear with the Nazis and the ‘Aryan’ identity and the position of that identity in relation to other, allegedly ‘inferior’ identities (Untermensch). Since World War II and in reaction to its ethnically created nightmares, a considerable and lively debate has taken place over the meaning of ‘ethnicity’ and ‘ethnic’ identity, and how to recognise such things – indeed, whether it is possible to recognise such things – in the archaeology. Ultimately, this comes down to whether objects, such as dress fittings, have an inherent ethnic identity and whether particular types of such objects would have been worn only by people of that ethnicity; thus an object betrays ethnic grouping.

Different modern nation states have developed different traditions of exegesis. In the German tradition the ascription of ethnic identities to features of funerary practice, such as deposition and especially object types, has been persistent, and publications regularly identify particular burials with specific ethnic groupings mentioned in the textual sources as being in certain areas at certain dates. This approach has been followed to a considerable degree in Spain (see below), where the influence of German workers has been strong, and to a lesser but still important extent in France, where emancipation of the archaeological evidence from the textual narratives has proceeded relatively slowly, and ethnic identification of burials and of grave goods still forms an accepted part of archaeological publication. The English-speaking tradition, along with some other European traditions, particularly the Dutch, has shown less fealty to the notion of ascribing ethnicities to burial practices and to objects; it has been more influenced by the development of postmodern (post-processual) concepts of the fluidity of identity and its signifiers. To workers in this tradition, objects have no inherent ethnic identity. The people who made them may have regarded themselves as belonging to a particular grouping, and so may the people who used or wore them, but not necessarily the same grouping, and the people who buried someone with such objects may have had their own views on the matter; none of them may have regarded an object or practice as belonging to a specific ‘ethnicity’. There is great doubt over the extent to which any such ‘ethnic’ identities were expressed through particular items of dress, and, of course, individual objects might pass through many hands. In addition, were these objects used only to construct statements about ‘ethnic’ identity, or were other aspects of identity, such as age, gender or status, being signified? Moreover, the ‘ethnic’ identification often rests on an unstated assumption that ‘Alan’ objects were only worn and used by Alans, whereas it is clear from burials that objects from different ‘ethnicities’ can be found in the same grave. In an ethnicist reading, one would have to argue something such as that the deceased was the issue of a mixed marriage: it is equally possible to argue that the objects were chosen because the deceased or their buriers liked them and had no ethnic intention in their deposition. Of course, neither tradition of study exists in isolation from the other, and there has been cross-fertilisation; nonetheless, there remains a difference along the lines sketched above.

Let us summarise what developments in understanding of the mutability of identity have meant. First they showed that it was ‘instrumental’; it could be changed if there was an advantage to do so. This led to the concept of ‘situational’ identity, one taken on as the optimal response to surrounding circumstances. The crucial realisation here was that ethnicity was not innate; rather it could be a result of birth but it could also be opted for and it could be changed. Ethnicity was something that happened in people’s heads, not in their genes: it was ‘cognitive’. This is not to say that this is in any way a weaker form of identity; human beings are capable of believing in such things passionately and to the death (others’ or their own). Moreover, such supposed signifiers of identity as language and religion are nothing of the sort: the modern world contains plenty of examples of speakers of a common language or co-religionists who are very good at hating one another (sometimes bringing us back to ‘the narcissism of small differences’). Halsall (Reference Halsall2007: 40) makes the point that individuals’ identities are also multilayered, and different aspects of them can be emphasised or downplayed in different circumstances. This necessarily means that identity is ‘performative’; the chosen identity must be displayed and acted out to be realised and reified. All this might seem a recipe for a sort of Humpty-Dumpty ethnicity: ethnic identity means what I want it to mean. But there are important constraints. First, and in particular, that individuals have to negotiate their identity with others around them, and this may impose severe constraints on what they can opt for. Second, and relevant for us here, identity can be ascribed to individuals by others (‘etic’) as well as, or instead of, being ascribed by individuals to themselves (‘emic’). An existing group may deny membership to someone wanting to join it, for any of a number of pretexts which seem to them entirely reasonable and compelling. Equally, a dominant group may ascribe to individuals or groups in a less powerful position an identity of its own choosing, one quite possibly not the choice of those thus identified. For the period we are concerned with, this can be particularly important, since it is clear that ‘barbarian’ identities were, at least in part, created as a reaction to how the Romans thought about other peoples (cf. Curta Reference Curta2007), with Roman views instrumental in creating ‘barbarian’ groups’ sense of self-awareness and self-definition (the Goths are a good example). These remarks in turn raise the important point that signifiers such as dress items were not just passive reflections of an existing identity (ethnic, status or other) but were also used actively to construct such identities, including constructing new, different identities that users had chosen to ‘situate’ themselves in and to ‘perform’, thus ‘falsifying’ their original identity as created for them by their parents and their wider social or ethnic grouping.

For late antiquity, work on the ‘ethnic identities’ of the period and what they may have meant and expressed has been particularly associated with the ‘Vienna school’ of Walter Pohl and his co-workers or the ‘Toronto school’ of Walter Goffart and his colleagues, which hold divergent views on how to interpret the nature and settlement of the ‘barbarian’ peoples. Both groups, though, have critically examined the textual sources for the various ethnic groupings of early medieval Europe, in particular the Goths, to see what they tell us about the ways in which ethnic identities were created and made evident, and why individuals or groups made the statements they did. They have shown that such identities were fluid and constantly being manipulated and recreated to fit the current situation, often under Roman influence, direct or indirect. The textual sources do allow us sometimes to approach what members of these groupings thought at the time, or more often what other people thought about them, above all what the Romans thought, since frequently what we have are Roman thoughts (with all their problems of ignorance and stereotyping) about societies that were often not in a position to give their side of the story to a distant Roman commentator working within an established frame of reference about ‘barbarians’. In all these modern studies, great stress has been laid on the concept of ‘ethnogenesis’. If we no longer accept fixed and immutable identities and their transmission down the generations, either for individuals or for groups, then there must be reasons for which and processes by which individuals and especially groups come to differentiate themselves from those around them and to construct ways of doing things that state these differences. Many of these ways of doing things, such as speech, will not be visible to the archaeologist; others, such as dress and appearance, may well be. It should be noted that, following the implicit framework of ancient commentators, the Roman provincial populations are not seen to have an ethnicity as such, other than provincial designations, though these do, of course, go back to perceived ethnic differences at the time of their incorporation into the empire. But by the Late Empire they are to an extent the ‘norm’ against which the ethnic groups are defined. As we shall see, this has led to a situation where their presence in the evidence and thus their contribution to the debate are often underestimated.

In what follows, the more sceptical approaches to ethnicity outlined above will be used in a discussion of the archaeological rather than the textual sources for ‘barbarian identity’. This discussion will therefore concentrate on the material-culture correlates of a range of possible identities, such things as objects, building types and settlement types. Above all, it will consider the funerary evidence, since in preparing a corpse for disposal, the living can make powerful statements about how they see, or would like to see, the identity of the deceased, and this, of course, includes such things as gender, age and status as well as claimed or ascribed ‘ethnicity’. In order not to get embroiled in a seemingly endless range of evidence and possible interpretations, the discussion will focus on the two ‘peoples’ mentioned above, the Visigoths and the Franks, who were crucial for the transformation of what had been the Western Roman Empire into the ‘barbarian’ successor kingdoms. Another major and well-documented (archaeologically as well as textually) people, the Alamanni, will not be dealt with in detail here because their main areas of activity and settlement were either on the periphery of our area of interest, in the Rhineland, or were outside the Rhine frontier altogether and thus fall outside the purview of this work: an excellent and up-to-date introduction to them, focusing primarily on the textual sources but with consideration of aspects of the archaeology, is provided by Drinkwater (Reference Drinkwater2007), and there is a comprehensive introduction to their archaeology by Theune (Reference Theune2004). After a look at the Visigoths and the Franks as case studies, more general conclusions will be drawn as to the role of ethnic identity and interaction in the transformation of the Roman West.

The Visigoths in south-west Gaul and Spain

The Goths are the most intensively studied of the Germanic successor peoples in the Roman West, thanks to a rich documentary corpus including narrative histories, chronicles, letters and saints’ lives written by men from the Roman world who came into direct contact with them or recorded their doings; in addition, and unusually, there are written sources produced by the Goths themselves – for the Visigoths in particular a series of law codes and the acta of a series of Church councils, emanating mainly from the Spanish kingdom in the sixth and seventh centuries. These have given rise to a compendious literature (for starters, see Collins Reference Collins2004; Ebel-Zepezauer Reference Ebel-Zepezauer2000; Heather Reference Heather1991, Reference Heather1996, Reference Heather1999), since the abundance of the written sources has made the Goths the case study par excellence for a Germanic people in the late antique period, the locus classicus for the study of ethnogenesis. This same abundance has often concealed the fact that the archaeological record is much less coherent, and for the Visigoths tells a rather remarkable story.

Let us recap in outline the historical narrative for the arrival and settlement of the Goths in the West. The Goths, or, as they then were, the Greuthungi and Tervingi, were allowed across the Danube in 376 and two years later inflicted on Rome one of her worst military defeats at the battle of Adrianople, in which the Eastern emperor Valens lost his life (for general discussions of the earlier parts of the story of the Goths, see Heather Reference Heather1991: Pt. II, Reference Heather1996: Pts. I and II, Reference Heather1999). In the latter part of the fourth century, they moved westwards, and in 410 under Alaric I they sacked Rome herself, a psychological shock to the entire Roman world. After the sack of Rome, they were manipulated out of Italy and into south-western Gaul, where, along with a group of Alans, they besieged Bazas (Landes), an event best known for causing the ruin of the poet Paulinus of Pella (grandson of Ausonius), before being cajoled into north-eastern Spain to act as imperial agents in the clearing out of other Germanic peoples who had got there in the aftermath of the collapse of the Rhine frontier and the failures of the usurper Constantine III. Finally, in probably 419 (traditionally 418), the patrician Constantius settled them in south-western Gaul from Toulouse down the Garonne valley to the Atlantic, granting hospitalitas rather than direct payment to support them. The terms on which the imperial authorities settled them have given rise to a huge literature concerning the precise meaning and significance of the term ‘hospitalitas’, one of those many late imperial euphemisms for something in reality more brutal; did they receive two-thirds of the land, two-thirds of the tax revenues or something else? (Barnish Reference Barnish1986; Durliat Reference Durliat1997; Goffart Reference Goffart1980: Ch. 4, Reference Goffart2006: Ch. 7; Liebeschuetz Reference Liebeschuetz1997; but see also Halsall [2007: 422–47] for a full review of the debate). This process was christened ‘accommodation’ by Goffart (Reference Goffart1980), in contradistinction to earlier visions of brutal replacement of Roman by German, making the whole process less threatening or violent, and ‘pacifying’ this piece of the past (for a critique of this tendency, see Ward-Perkins Reference Ward-Perkins2005: 5–10). By now the interests of these people clearly lay in the West beyond the Alps, leading them to be described in due course as the Visigoths (western Goths) in contradistinction to the groups which later settled to their east in Italy, the Ostrogoths (eastern Goths).

The settlement of the Visigoths was established under Roman suzerainty and quite possibly as a supposedly temporary expedient; originally, it is very unlikely that either Goths or Romans saw this settlement as implying the creation of an independent political entity rather than simply as a convenient solution to a particular problem. But the developing weakness of the Western Empire meant that gradually the Visigoths came to regard themselves as free agents, and their leaders became kings with their seat at Toulouse. By the mid fifth century, the Visigothic kingdom had taken on a life and identity of its own, and its kings became important players in the political chess of the mid to late fifth century, with Aetius trying and failing to defeat them in 439. But the Visigoths put themselves under his command against the Huns at the battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451. Afterwards, under Theodoric II, they intervened more deeply into Spain, defeating the Suevic kingdom in 456 and pinning it back into the far north-west; in Gaul they gained Narbonne in 462/3. In 466 Theodoric II was assassinated and replaced by Euric I, who pursued an overtly aggressive policy of expansion, capturing Pamplona, Zaragoza and Tarragona in 473, thus coming to dominate the northern third of Spain, and finally taking Arles and Marseille in 476 (the previous year he had taken Clermont-Ferrand, whose bishop, the author Sidonius Apollinaris, had organised the resistance to the Visigothic takeover, but Sidonius was sold down the river by the imperial authorities in an attempt to hold onto Arles and Marseille – not one of their more successful gambits). The political opposition of the Visigothic kingdom to what remained of the Western Empire was emphasised by the fact that the Visigoths were adherents of the Arian branch of Christianity rather than the Catholic profession of the imperial authorities; Euric I was militantly Arian and anti-Catholic. By his death in 484, the Visigoth Euric I not only controlled south-western Gaul but was also master of much of Spain save the Suevic enclave in the north-west. Under his son Euric II and Euric II’s son Alaric II, the Visigothic kingdom was clearly the major player in the former Western provinces of the Roman Empire. But there was to be one more roll of the dice; in 507 the Franks from the north under Clovis brought the Visigoths of Toulouse to battle at Vouillé near Poitiers and defeated them, killing Alaric II. Thereafter the Visigoths regrouped in Spain; north of the Pyrenees they held only the coastal fringe along the Mediterranean in Septimania. From the early sixth century, the Visigothic kingdom in Spain acquired the trappings of statehood such as law codes, coinage and wars of succession.

South-west Gaul

The textual sources therefore clearly present us, in the case of the kingdom of Toulouse, with a Germanic group with a defined identity; a monarchical, aristocratic and warrior society; a defined, stable and expanding territory; in what proved to be the twilight year of the kingdom, a legal system (the Breviarium of Alaric, 506); an ecclesiastical structure (Council of Agde in 506); and, at the level of the kings at least, clear notions of where the interests of the Visigoths lay distinct from those, including the Romans, around them. So how is this reflected in the archaeology of south-western Gaul, its Germanic settlements, structures, burials and material culture? Not at all well – an important exception is James, E. (1977), as is perfectly well known, but often glossed over by omission through concentrating on the written sources. The homelands of the Goths have long been identified by archaeologists, working in a culture-historical paradigm, with the area of the second- to fourth-century Sîntana de Mureş-Chernyakhov culture in the region to the north-west of the Black Sea outside the Roman lower Danube frontier (see Heather and Matthews Reference Heather and Matthews1991 and references), where there was a range of material culture, including brooches, belts and pottery, that is relatively distinctive. This culture was later to be found further west into Roman territories, and is taken to be evidence for the migration of the Goths into the empire in the second half of the fourth century. Reviews of ‘Germanic/Gothic’ material culture in fifth-century south-western Gaul have repeatedly come up with little more than a handful of sites and material (Ebel-Zepezauer Reference Ebel-Zepezauer2000; James, E. Reference James1977, Reference James1991; Périn Reference Périn1991; Rouche Reference Rouche1979 – the blank on Ebel-Zepezauer’s distribution map of ‘Visigothic’ metalwork [2000: Abb. 1] where the kingdom of Toulouse should be is striking – Stutz Reference Stutz2000). There is a small handful of material in the south-west of types deriving from the Sîntana de Mureş-Chernyakhov culture, consisting of four bone combs (Kazanski and Lapart Reference Kazanski and Lapart1995) of a very distinctive form, rectangular with a semicircular projection on the upper side. These items come from sites in a triangle formed by the cities of Agen, Auch and Eauze to the west of Toulouse, namely the villas of Montréal-Séviac and Moncrabeau-Bapteste (Lot-et-Garonne) between Eauze and Agen, and that at La Turraque, Valence-sur-Baïse (Gers), between Eauze and Auch. It should be noted that similar combs have also been recovered from Trier and other sites in the area (Cüppers Reference Cüppers1984: 345), so, though they are of non-Roman type, they are not necessarily solely ‘Gothic’. The combs are of interest, though, not just for the links they provide with the home areas of the Goths, but also for their function; they reflect the importance of hairstyle, a recurrent indicator of barbarian identity among Roman writers. Current research in the région of Midi-Pyrénées is adding to this corpus (J. -L. Boudartchouk, pers. comm.), but it is unlikely to change radically the impression of relatively little ‘foreign’ material culture through the course of most of the fifth century. One other indicator of non-local individuals is the group of four or so burials of people with deliberate cranial deformation carried out in infancy (Crubézy Reference Crubézy, Austin and Alcock1990) from south of the Garonne and, unfortunately, not well dated. Traditionally linked with the Huns (see below, p. 381), such burials in Gaul are small in number and mainly of adult females, suggesting the marrying of individuals whose origins lay in central Europe into populations further west; if so, they are not a good indicator for Visigothic identity.

Telling is the archaeology of fifth-century Toulouse, seat of the kingdom. In terms of material culture, there is a group of six Armbrustfibeln from the city and its environs (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Boudartchouk, Cazes, Rifa and Stutz2002: 534, 536), but this is a type with a wide distribution within the Germanic culture-province, so it cannot be specifically linked to a Visigothic identity. There are also three brooches of the Duratón type (Bach et al. Reference Bach, Boudartchouk, Cazes, Rifa and Stutz2002: 535, 537), a type whose main distribution lies in Spain, where it has traditionally been a marker of ‘Visigothic’ settlement, though such easy equivalence is now under serious question (see below, p. 366). It is only at a horizon datable to the turn of the fifth and sixth centuries, immediately before the Frankish conquest, that more items of apparel of ‘Germanic’ type are recorded from the city; this is a horizon we shall return to below, since it is an important one all across what the texts tell us had become the Visigothic realm. By contrast, there is very little ‘Germanic’ visible in the ceramic assemblages of the fifth century from Toulouse, which remain dominated by utilitarian, local productions in the Gallo-Roman tradition along with DSP of both ‘Atlantic’ and Languedoc types and a tiny amount of African amphorae and ARS (Dieulafait et al. Reference Dieulafait, Boudartchouk and Llech2002), though again recent research has identified a number of pieces of pottery whose parallels lie in eastern Europe, but numerically they are a minute group compared with the overwhelming dominance of Roman provincial ceramics. This is true also of other assemblages in the region, such as that from the fifth-century deposits in the upper town of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges (Dieulafait Reference Dieulafait2006), where the ceramics remain resolutely Roman provincial.

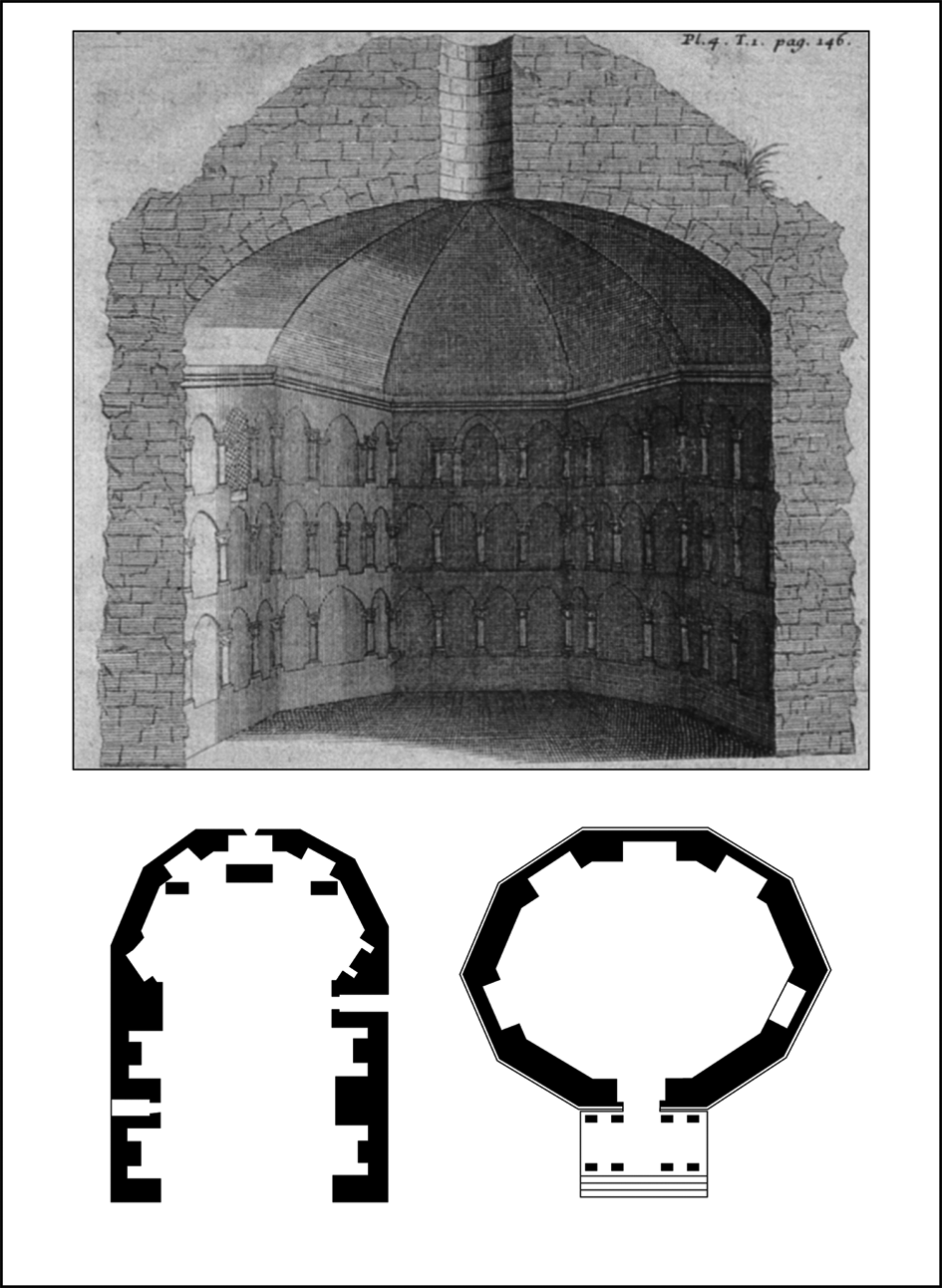

When we turn to structures, rather than material culture, recent excavations in and around the walls of the city, combined with re-evaluation of antiquarian observations, have yielded a complex of sites in the north-western area (Figure 8.2). The largest and most striking of these is the site of the Hôpital Larrey just inside the north-western angle of the enceinte (for a summary, see De Filippo Reference De Filippo2002). A building range probably some 90 m long by 30 m wide had a central entrance way with, to either side, large internal courts with, originally, large apsidal terminals against the sides of the entrance. Along the façades of the building were two long galleries or suites of rooms. Because of the later demolition of the building and clearance of the site, the dating evidence was sparse but pointed to the first half of the fifth century. Another major structure of similar date lay a little to the north-west outside the walls, to the north of the later church of Saint-Pierre-des-Cuisines (Cazes and Arramond Reference Cazes and Arramond2002), consisting of a roughly east–west gallery façade with central entrance way. Large-scale constructions of this date were rare anywhere in the West. This has led some to postulate that these structures reflected the new power at Toulouse and to suggest that the Hôpital Larrey site in particular may have been part of the palace of the Visigothic kings. Following on from this suggestion, it was then proposed that the core of the medieval church of Notre-Dame de la Daurade (Cazes and Scellès Reference Cazes and Scellès2002), unfortunately destroyed in 1761 but of which engravings exist (Figure 8.3), was associated with the Hôpital Larrey site, lying as it did only some 250 m to the south-east. This church was a curious polygonal structure with an interior richly embellished by niches framed with marble colonnettes inlaid with gold mosaic, and the niches decorated in gold-ground mosaic with three registers of biblical personages and scenes. Clearly, this was one of the richest and most elaborate programmes of decoration known anywhere in the West at this date (the fifth century). Its function remains unclear. It has been posited to be a royal mausoleum, but its position within the walls makes this less likely. Many prefer to interpret it as the palace chapel of the Visigothic kings (mentioned in Sidonius Apollinaris’s idealising account of his visit to the court of Theodoric II in 455 – Epistulae II.i), and the proposal that the iconography of the mosaics may have reflected Arian theology would fit since the Visigoths were still adherents of that heresy in this period. It should by now be clear that, first, there is no proof positive that these structures had anything whatsoever to do with the Visigothic kings, and that, second, the reason why they are so difficult to claim as ‘Visigothic’ is that in plan, layout and what is known of the decoration they were solidly Roman provincial, with, for example, the best parallel to the Hôpital Larrey plan to be found at the villa of Nérac (Lot-et-Garonne) to the north-west of Toulouse (Balmelle Reference Balmelle2001: 390–3). This echoes the evidence from the countryside for the archaeological near invisibility of the Visigoths.

Why then this near invisibility for the first fifty years or so (a couple of generations) of the kingdom? This must relate to the experience of the Goths prior to their settlement in Aquitaine and to the circumstances of their settlement and subsequent integration. As has been pointed out on various occasions, prior to their arrival in Gaul, the Goths had spent some forty years touring the central areas of the Roman Empire: cultural influences can flow both ways, and in this case rather than Romans adopting ‘barbarian’ fashions, it appears that the Visigoths were ‘Romanised’. After the sack of Rome in 410, they were clearly under the control of the patrician Constantius, who used them as a proxy for the much weakened Western Roman army in both Gaul and Spain. So by the time they were settled between Toulouse and the ocean, they were thoroughly accustomed to Roman ways (Alaric I’s successor Athaulf had even been married to the emperor Honorius’s sister Galla Placidia during the Goths’ brief sojourn in Barcelona) and must have been using the Roman vocabulary and semiotics of rank and power alongside any of their own. Given that the Roman government formally settled them in the south-west with a treaty and with fiscal provision rather than their invading and taking over, they probably had more to gain from accommodation with the existing system in this very wealthy area, studded, as we saw in Chapter 5, with some of the largest and most splendid villas of the period, housing rich and powerful landowners. It looks as though the first couple of generations of Visigoths adapted to the existing Gallo-Roman style rather than the Gallo-Romans adapting to the Visigothic, so what the well-dressed Visigothic warrior of the mid fifth century wore and fought with is rather a difficult problem for the archaeologist. But as noted above, in the last third or so of the fifth century this started to change, and the ‘Visigoths’ become more visible in the archaeology, and it is this change and the reasons behind it that will be considered below in conjunction with the evidence from Spain (p. 375).

Spain

The Iberian peninsula in the fifth century saw, according to the texts, a whole range of different Germanic peoples, Alans, Sueves, Vandals (both Asding and Siling) and Visigoths, either passing through or carving out for themselves territories at the expense of the Roman state and the Hispano-Roman population, such as the kingdom of the Sueves centred on the late Roman province of Galicia and eventually, in the sixth century, the Visigothic kingdom encompassing the entire peninsula. The historical sources for the period are of varying forms and degrees of narrative reliability (the latter was often not their purpose) and have given rise to a huge literature of possible scenarios for what was going on and why, though it is generally agreed that many of the ‘barbarian’ peoples, such as the Vandals, left next to no trace in the archaeology, usually because they were too transient (see Arce Reference Arce2005a, Reference Arce2005b for a balanced and judicious treatment of the sources and of the history of the fifth century). The Visigothic period in Spain has received a great deal of attention from historians because of its central place in the creation of hispanidad through the forging for the first time of a state comprising the whole peninsula, a state, moreover, that was Christian – indeed, we know most about that state through the decrees of a whole series of Church councils. This state was to be overthrown by the Muslim Arabs from 711, leading to the nearly eight hundred years of the reconquista culminating in the expulsion of the Moors by Los Reyes Católicos in 1492, the crucible in which the Spanish ‘national identity’ was formed (cf. Collins Reference Collins2004: Introduction). In addition, ‘Visigothic’ has also become a chronological and architectural/art-historical style, as well as an ethnic appellation, but that is for a period later than is our concern here. Because of our knowledge of the development of the Visigothic kingdom in the sixth and seventh centuries, there has inevitably been a certain amount of reading back from later conditions into the late fifth century (for instance, of the later legal bans on intermarriage between Goths and Romans, ironically recycling late Roman legislation which saw the problem from the other side) and of the use of the textual sources to condition study of the archaeological material. Here the intention is much more limited; it is to look at the development of what has been interpreted as a ‘Visigothic’ material culture, particularly in the northern part of the peninsula, in the fifth century and to relate this to developments in Septimania (roughly modern Languedoc-Roussillon) and in the Toulouse region.

The Iberian peninsula has yielded a large number of cemeteries that contain burials equipped with items of dress, equipment and personal adornment that were clearly not of Roman provincial types (Figure 8.4). These burials and cemeteries could be dated to the fifth to eighth centuries from the Roman-style objects in them and from parallels to the non-Roman material elsewhere in Europe (for a clear introduction to and summary of the archaeological evidence and the analyses thereof by a range of workers, see López Quiroga Reference López Quiroga2010: esp. Ch. 3). They were concentrated on the Meseta of the central and northern parts of the peninsula, but there were examples of them more or less over the whole peninsula (cf. Ebel-Zepezauer Reference Ebel-Zepezauer2000: Abb. 1) if we include the entire date range. Here our concern must be with the earlier part of the sequence, datable to the fifth century. In the 1940s, the excavation at two sites above all, Duratón (Segovia) and El Carpio de Tajo (Toledo), produced relatively large cemeteries with some graves containing numbers of ‘barbarian’ objects, associated for the most part with female burials and betokening a form of clothing different from that current among the female Hispano-Roman population. The objects were principally brooches, Armbrustfibeln, Bügelknopffibeln and Blechfibeln with some of the rarer Adlerfibeln (in the form of an eagle usually with cloisonné decoration). These were usually worn in pairs at or near the shoulders, suggesting females buried in a two-part tunic or peplos. Associated with these were elements of belts, most usually buckles, often with rectangular plates decorated in a variety of ways but most characteristically with polychrome cloisonné work. Another frequent find was necklaces, generally of glass beads but sometimes of other materials including amber; also occasionally found were earrings. It will be noted that what we have here are female graves with a distinctive, non-Hispano-Roman style of dress. The male graves were much less distinctive and in fact seem to be assimilated to Hispano-Roman traditions of burial (see below). In the intellectual framework prevailing at the time these cemeteries were excavated, particularly that created by German scholars such as Kossinna, these were seen as evidence for the movement of groups of ethnically distinct peoples of Germanic origin across Europe and settling ultimately in Spain. From that it was only a short step to accepting that these were the burials and cemeteries of the Visigoths, who, the texts stated, had moved over the Pyrenees in the latter part of the fifth century. For instance, a Spanish text, the Chronica Caesaraugustana, spoke of the settlement of the Goths between 494 and 497, and this was assumed to have been reinforced by refugees from north of the Pyrenees after the defeat of the kingdom of Toulouse at Vouillé in 507. Since at the time workers lacked independent dating for the burials, this gave a terminus post quem for the appearance of these burial rites and objects.