Book contents

- Russia and Courtly Europe

- New Studies in European History

- Russia and Courtly Europe

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Book part

- Notes on Transliteration, Spelling, and Dates

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1 Barbarous Ceremonies? Russia’s Places in Early Modern Diplomacy

- 2 Facts and Fictions

- 3 Through the Prism of Ritual

- 4 Stage and Audience

- 5 From Insult to Imperator

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

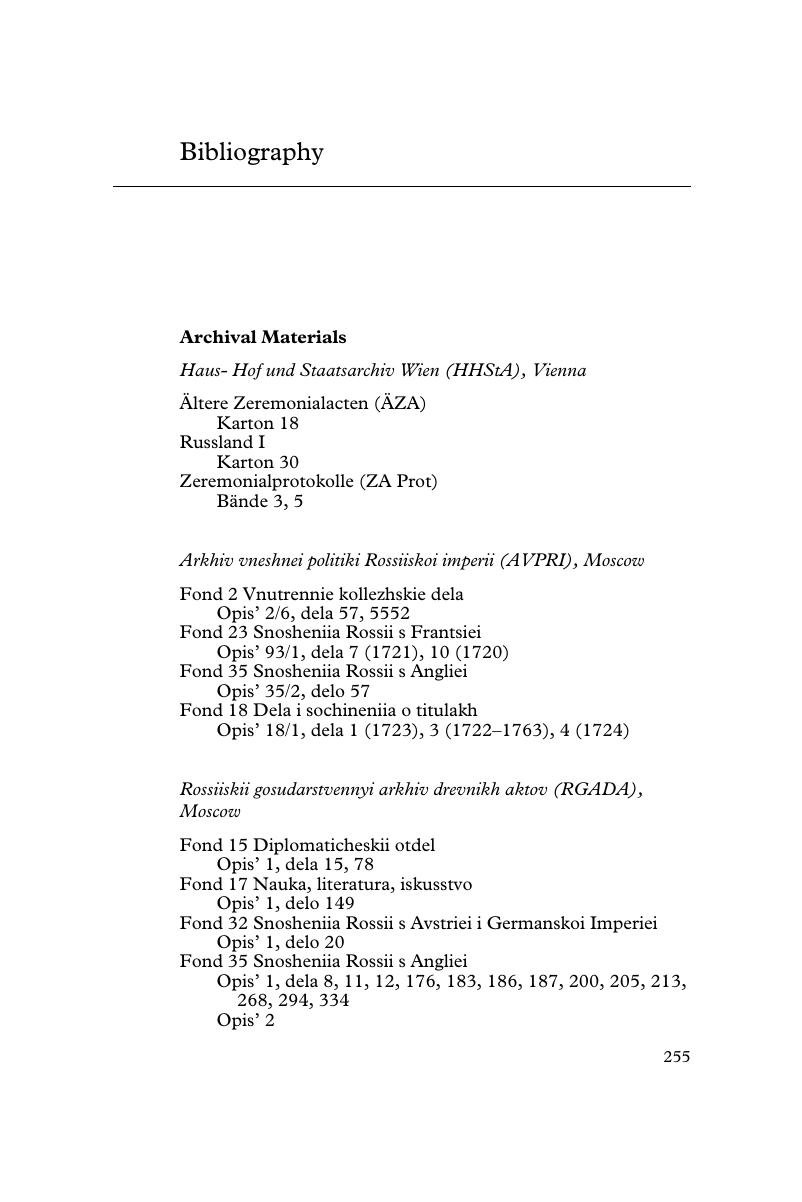

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 October 2016

- Russia and Courtly Europe

- New Studies in European History

- Russia and Courtly Europe

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Book part

- Notes on Transliteration, Spelling, and Dates

- Glossary

- Introduction

- 1 Barbarous Ceremonies? Russia’s Places in Early Modern Diplomacy

- 2 Facts and Fictions

- 3 Through the Prism of Ritual

- 4 Stage and Audience

- 5 From Insult to Imperator

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Russia and Courtly EuropeRitual and the Culture of Diplomacy, 1648–1725, pp. 255 - 291Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016