Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

4 - Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Preface

- A note on transliteration

- Glossary

- 1 Joseph Stalin: power and ideas

- 2 Stalin as Georgian: the formative years

- 3 Stalin as Commissar for Nationality Affairs, 1918–1922

- 4 Stalin as General Secretary: the appointments process and the nature of Stalin's power

- 5 Stalin as Prime Minister: power and the Politburo

- 6 Stalin as dictator: the personalisation of power

- 7 Stalin as economic policy-maker: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1936

- 8 Stalin as foreign policy-maker: avoiding war, 1927–1953

- 9 Stalin as Marxist: the Western roots of Stalin's russification of Marxism

- 10 Stalin as Bolshevik romantic: ideology and mobilisation, 1917–1939

- 11 Stalin as patron of cinema: creating Soviet mass culture, 1932–1936

- 12 Stalin as producer: the Moscow show trials and the construction of mortal threats

- 13 Stalin as symbol: a case study of the personality cult and its construction

- 14 Stalin as the coryphaeus of science: ideology and knowledge in the post-war years

- Index

Summary

The sources of Stalin's power is one of those subjects that are much described and little studied. The scores of political biographies and general histories covering the Stalin era suggest a variety of possibilities, from the use of terror and propaganda to the appeal of his policies, but almost without exception they mention Stalin's position as General Secretary. The common story suggests that, as General Secretary, Stalin used his control over appointments to build a personal following in the Party apparatus. The mechanics of this process are sometimes referred to as ‘a circular flow of power’. Stalin appointed individual Party secretaries and gave them security of tenure. In return, they voted for him at Party Congresses. It is generally taken as given that Stalin used the power this afforded him to remove his political rivals in the course of his rise to power, and in later years, to remove those officials who had reservations about his policies. In short, Stalin's power over appointment is commonly understood not only as a key factor in his rise to power, but also as the origin of his personalistic dictatorship.

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, ‘revisionist’ scholars began to cast doubt on the idea that Stalin could be sure of the personal loyalty of Party officials and that they would unquestioningly execute his will. Since the opening of the archives, a substantial body of new evidence has reinforced their views.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

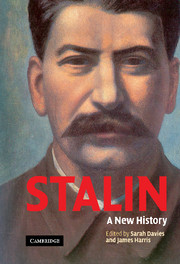

- StalinA New History, pp. 63 - 82Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2005

- 5

- Cited by