I Introduction

This chapter analyses the recent land reform that was enacted by the 2013 Code Foncier et Domanial (Land and Domain Code) and its results at end 2018, five years after.Footnote 1 Its orientation is significantly different from the other chapters, both in its purpose and approach. It is not so much a question of highlighting desirable areas for reform as it is of analysing an ongoing reform. In particular, it deals with the political economy of the reform. It provides a detailed history of a complex and contradictory process, discussing the reform’s political and economic stakes, the groups of actors and interests that pushed it, those who are opposed to it, and those who seek to shape it for their own benefit.Footnote 2

A matter of ‘power, wealth, and meaning’ (Shipton and Goheen, Reference Shipton and Goheen1992), land is at the heart of societies and of the formation of the state: (1) the way of thinking and organising access and control of land and its resources reflects the conception of the society, its forms of authority, and the differentiations that structure it; (2) the distribution of rights over land and resources determines, in part, statutory and socio-economic inequalities; and (3) the capacity to define rules governing land rights, and to grant or validate them, is at the heart of political power and construction of the state (Boone, Reference Boone2014). Any land policy necessarily has power-related stakes (politics) and societal stakes (polity) (Léonard and Lavigne Delville, Reference Léonard, Lavigne Delville, Colin, Lavigne Delville and Léonard2022). Land reform processes are also linked to the interests of the different groups of economic and political actors, the weight of professional corporatism, the conflicts of societal projects, and the question related to the plurality of norms that run through the society (Lund, Reference Lund and Winter2001).

Since the middle of the 1980s the land issue in Africa has come back again onto the agenda of development policies, in a context of state crises, economic liberalisation, and increased conflicts in rural areas. Two major visions clash, both challenging the colonial and post-colonial state’s monopoly on land. The first one promotes the replacement of informal customary rights, considered as obstacles to productivity, by private ownership rights, supposed to be a condition for economic development. The other one, described as ‘adaptative’ (Bruce, Reference Bruce1992) or ‘pro-poor’ (Borras and Franco, Reference Borras and Franco2010; Zevenbergen et al., Reference Zevenbergen, Augustinus, Antonio and Bennett2013), acknowledges the dynamics of local/customary land rights and considers that they are not, as such, a constraint on productivity. Thus, the issue of land reforms is to build a favourable institutional environment that secures people’s rights and allows these rights to evolve peacefully.

Both paradigms emphasise the issue of the security of land rights, but with different assumptions regarding what ‘tenure security’ means. For the privatisation paradigm, it means private ownership rights recognised by the state and full capacity of transfer and sale. It is however a biased definition. Land tenure security means that one’s rights (of whatsoever kind) cannot be challenged without good reason, and that legitimate authorities (customary, state, or hybrid) are able to settle conflicts (Lavigne Delville, Reference Lavigne Delville2006).Footnote 3 Tenure security is above all an institutional issue: it requires rules and authorities able to design and enforce them; one can be in security with informal rights, which is the case in most customary contexts. While emphasising tenure security, the ‘adaptation’ paradigm also largely supports the formalisation of customary informal land rights in rural areas. However, according to this paradigm, formalisation has to adapt to the diversity of rights and to be implemented through progressive frameworks, and the development of innovative, adapted, inexpensive, and accessible approaches.

In French-speaking Africa, the debate on the legal recognition of property rights is strongly structured around land titles,Footnote 4 issued after ‘immatriculation’. Immatriculation is a land registration procedure that had been specifically designed for colonial areas (decrees of 1906 and 1932). In contrast to France, where the proof of ownership is the sale contract prepared by notaries, it is based on the granting by the state of a quasi-absolute private ownership, incontestable and guaranteed by the state, based on the purging of all pre-existing rights. Every plot that does not have a land title is subject to informal rights or ‘presumed ownership’ and is considered to be part of the state’s private domain. Immatriculation (hereafter referred to as standard titling or registration) allows for ‘the entry into legal life’ of land that previously had ‘informal’ status. However, it is a complex and costly procedure and colonial powers never tried to generalise it (Chauveau, Reference Chauveau, Lafay, Le Guennec-Coppens and Coulibaly2016). Historically, it has been at the service of colonial power and its allies, and not of the recognition of the rights of inhabitants, who were considered as subjects and not citizens (Mamdani, Reference Mamdani1996). It has been retained after independence and remains accessible only to a minority.

For the majority of West African land professionals and policy makers, the land title is the only conceivable form of legal property right and the aim of a reform is to unify land rights and to generalise private ownership and land titles. For some of them, and for most sociologists or anthropologists, standard titling is an obstacle to large-scale access to land rights formalisation, since its very logic – not to mention its cost – is contradictory to the aim of recognising the various existing land rights. In this conception, it is the law that has to adapt to society in order to overcome the colonial legacy.

The debate on agricultural productivity and on the relations between society and law is not only a technical one. It encompasses diverse conceptions of society, of relations between individuals, social collectives, and the state, of the place of market relations, of the role of law, and so on. It challenges people’s historical exclusion from access to the law. These various and intricate issues explain why, even though almost every West African country has launched attempts at land reform, the processes and outcomes, as well as the degree of implementation of adopted reforms, have been very different from one country to another (Seck et al., Reference Seck, Lavigne Delville, Richebourg, Vaumourin and Mansion2018).

The case of Benin is particularly interesting from this point of view because, within the space of a few years (from 2007 to 2013), Benin adopted two different contradictory land reforms. The first was led by the Ministry of Agriculture and supported by European donors. It focused on rural areas and promoted an alternative to standard registration and land titles, which the promoters considered fundamentally unsuitable for rural areas. It resulted in the 2007 Rural Land Law.Footnote 5 The second has a national focus. It was led by the Ministry of Urban PlanningFootnote 6 and the Millennium Challenge Account Benin (MCA-Benin).Footnote 7 It aims to standardise land law and develop access to private land titles by reforming the national land administration. It was embodied by adoption of the Land and Domain Code in 2013 (which abolished the 2007 law and was slightly revised in 2017), and the establishment in 2016 of the Agence Nationale du Domaine et du Foncier (ANDF, National Agency of Land and Domains).

The succession, within a few years, of two reforms based on different paradigms, carried out by different networks of actors, supported by different donors, and having experienced varying degrees of implementation, represents a textbook case for highlighting the intricate issues of land reform, and questioning the stakes and the actors’ interests around the reform’s framing and implementation. It also offers an opportunity to question the diverse conceptions of land tenure security and of land governance and the conditions for institutionalising a land reform.

In this chapter, I study the history of these two intricate land reforms, with a focus on the second one, which – at the end of 2018 – won the battle. I begin with a brief institutional analysis of the land sector in the early 2000s. Section II discusses the different, concurrent reform projects that took place during the 2000s. Section III details the vision and process of the second reform, with its dual focus on field registration projects and land law formulation. I then analyse the 2013 Land Code, its orientations and the controversies around it, and finally discuss the strengths and limitations of this reform, particularly in terms of citizens’ inclusion.

My analysis relies on a perspective of ‘socio-anthropology of public action in countries under aid regime’ (Lavigne Delville, Reference Lavigne Delville2016), which aims at studying through qualitative enquiries the way public policies are framed, negotiated, contested, and implemented in aid-dependent countries. In an ethnographic and constructivist approach, it studies the interplay of actors and conflicts of representation and interests throughout the policy process, taking into account the multiple disjunctions between its different stages. By empirically following networks of actors, ideas, and instruments, from the global to the local, this approach shows the intertwining of ideas, interests, and institutions (Hall, Reference Hall, Lichbach and Zuckerman1997), and the intricate issues of policy, politics, and polity. This analysis focuses on a reform that is still being implemented and ends with the National Workshop on Land organised in October 2018. The chapter therefore concerns an incompletely stabilised process, and in no way claims to evaluate it. Focusing on retracing the reform’s history, it offers primarily a retrospective look, and does not intend to take note of recent developments. However, some of them are presented in the Afterword.

II Competing Projects for Reforming Land Law and Administration (1990–2005)

A State Ownership, Informality, Semi-formal Arrangements and ‘Confusion Management’: A Brief Analysis of the Land Sector in the 1990s–2000s

From independence up to the 2007 Rural Land Law, land in Benin was governed by a legal framework resulting from the early years of independence (Gbaguidi, Reference Gbaguidi1997):

Law No. 65–25 of 14 August 1965 on land ownership in Dahomey,Footnote 8 which largely incorporates the colonial registration procedures defined by the 1932 decree.

Law No. 60–20 of 13 July 1960, established the system of ‘housing permits’ in Dahomey, which made it possible to grant ‘essentially personal, precarious and revocable’ rights to urban actors established on the private domain of the state.

Law No. 61–26 of 10 August 1961 defining and regulating rural development schemes (périmètres d’aménagement rural).

As in most French-speaking African countries, the colonial decrees of 1955 and 1956 were set aside by the new authorities. Enacted at the end of the colonial period, those decrees allowed ‘indigenous’ people to obtain legal recognition of their land rights. Rarely implemented, they have never formally been repealed before the 2013 Code, and were sources of inspiration for the 2007 rural land reform (Lavigne Delville and Gbaguidi, Reference Lavigne Delville and Gbaguidi2022).

Throughout this period (1960–1990), the widespread informality was not necessarily perceived as a policy problem in rural areas, where customary and semi-formal regulations continued to organise access to land and conflict arbitration. Land tenure insecurity was mostly found where the state was involved in development projects, and where the land market was developing, mainly in urban or peri-urban areas. This section describes the situation around 2000, when reform processes began. Since the reform is still partly implemented, it has not changed very much in most of the country.

Decentralisation policy in 1999 transformed the former districts into communes, giving them expanded powers on land and housing, and land became a central part of the local political economy (Aboudou et al., Reference Aboudou, Joecker and Nica2003).

1 Generalised Informality, Institutional Weaknesses and Semi-formal Arrangements

Around 2000, land tenure informality (or semi-formality) was largely dominant. Across the entire country only 1,980 titles were issued between 1906 and 1967 (Comby, Reference Comby1998b, pp. 11–12). Demands for land titles, mostly from urban well-off citizens, have risen since the 1990s, along with economic liberalisation and democratic transition. However, in 2004 there were only 14,606 land titles (MUHRFLEC, 2009) for a population of 6,769,914 inhabitants in 2002 (Zossoungbbo, Reference Zossoungbbo2016). Titles covered less than 20,000 ha or 0.17 per cent of the national territory. They concerned fewer than 15,000 households (1.23 per cent of the total number; République du Bénin, 2004). In 2007, only 5 per cent of urban residents and 0.8 per cent of rural residents had land titles (INSAE, 2009, p. 166), with high inequalities by wealth level: 4.4 per cent of the ‘richest’ had a land title, compared to 1.1 per cent of the ‘poorest’ (INSAE, 2009, p. 167). While the demand for titles increases, the pace is slow: ‘the proportion of parcels or land with a land title rose from 2.1% in 2006 to 3.4% in 2010 and 3.0% in 2011’ (INSAE, 2012, p. 53).

The responsibility for the management of both the state domain and private land titles is entrusted to the Direction des Domaines, de l’Enregistrement et du Timbre (DDET, the Directorate of Land Tenure, Registration and Seals), within the Ministry of Finance. DDET is a highly centralised body: it has only two offices, in Cotonou and Porto Novo, for the full country. Under-equipped, the land administration delivers few titles. Many files are incomplete or outdated. A survey done for a World Bank Project (Comby, Reference Comby1998b) states that many old titles are practically unreadable, due to poor storage conditions, and that some are even destroyed or missing. In the absence of a cadastral plan, the existence of a land title can only be known through a survey among neighbours. The plot maps drawn up by the surveyors are not connected to a general system of topographical markers, and the location of some titled plots is inaccurate. A new title can thus be issued on a plot of land that has already been titled in whole or in part (see Comby, Reference Comby1998b and Lavigne Delville, Reference Lavigne Delville, Bourguignon, Houssa, Platteau and Reding2019 for details).

The titling procedure is supposed to guarantee the reliability of the information. However, the number of steps in that procedure increases its costs and duration. This also increases the risk of the file becoming bogged down, and therefore the opportunities for personalised and clientelist, if not corruptive, processing of the files. Contradictory demarcation on the plot itself is supposed to ensure the legitimacy of the claimed rights. However, demarcation notices are to be published in the State Gazette, and posted in the Court of First Instance and in the subprefecture or town hall. They are rarely posted on the plot of land itself. Information on neighbours and possible local rights holders is fragmentary or non-existent. Applicants can thus obtain a title even with incomplete or sometimes illegal files and/or without the customary holders of the land in question being informed. The impossibility of contesting a title, which is supposed to protect the owner, serves in practice to ratify errors, fraud, and spoliation.

Applicants for titles are essentially wealthy urban actors, who are familiar with land administration and who want to secure their rights on the plots they have purchased, mainly in peri-urban areas. However, many executives – and even lawyers – acknowledge that they do not go through with the procedure: they start it in order to have a surveyor demarcate the plot on the field to discourage possible claims. Then they stop. The state itself rarely carries out registration procedures on its own land and the consistency of the state’s domain is unclear. The text defining the price for buying state land has not been updated since the 1960s, allowing actors familiar with the procedures to buy at low prices portions of the private domain of the state, which has been largely discounted over the years (Lassissi, Reference Lassissi2006).

The revolutionary regime (1974–1990) did not bring significant changes. It did not nationalise the land and forbid land sales. The 1977 Basic Law recognised and protected private property. This period saw the creation of numerous state farms on land expropriated from farmers, and the allocation of ‘uncultivated’ land to state companies and administrative services, with redistribution to clients and political allies (Le Meur, Reference Le Meur1995). The promotion of palm groves led to the creation of cooperatives where state agents could gain land. Until today those cooperatives remain sites of conflict between members of cooperatives and former customary owners. Furthermore, the official ban on owning more than one urban plot of land has multiplied bypass strategies, at the risk of subsequent conflicts during succession when some plots were put into the name of children (Andreetta, Reference Andreetta2019, p. 118).

Sitting beside the land law, or reinterpreting it, various procedures, most of them dating from the colonial period, have gradually constituted a ‘semi-formal system’ (André, Reference André, Lavigne Delville and Mathieu1999; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu and de Villers1996) of land regulation; that is, a set of procedures and documents not explicitly integrated into the legal framework but nevertheless implemented in a relatively stable way, by official authorities. This is the case for customary/unregistered land. For example, local authorities (formerly the district heads, now the mayors) issue administrative certificates – normally after a field survey but not always – to attest the ownership of a plot of untitled land. They also validate sales contracts on untitled land by signing and stamping them, with reference to the colonial 1906 decree on agreements between indigenous people. Local authorities also widely distribute housing permits, including outside land registered in the name of the state, which is illegal (Le Meur, Reference Le Meur2008).

In other countries, transactions on unregistered plots can be formalised through written contracts, handwritten or typed, which are officialised with the signature of an administrative or communal authority. This is much more institutionalised in Benin, despite some variations: municipalities print and sell specific forms with the commune stamp. Most land sales are officialised this way, against payment of a tax. However, this institutionalisation does not prevent all conflicts over sales, for several reasons. Field surveys are not always done before issuing administrative certificates. When signing a land sale contract, the mayor has no means to ensure that the seller is really the owner and has the right to sell. A ‘certificate of non-litigation’ (attestation de non litige) is requested from the village chief, but is not enough as the chief has no obligation to check the property rights on the plot and to alert in case of risk. Moreover, while numerous sales concern family land, the form has room only for an individual seller, and there is no obligation to have formal approval of the sale by the family rights holder before endorsing a sale. Archives are not properly managed. Communes have multiple responsibilities in terms of housing and planning, without having the tools and staff that would be necessary to carry on these responsibilities. Commune leaders are often engaged in land business, due to its political and financial issues.

Outside buyers cannot rely on their knowledge networks to check whether the person claiming to sell a plot of land is really the owner and whether the plot is a family property or not, and are not on site after the purchase to protect the plot against fraudulent sales. They are thus are particularly vulnerable to conflict and insecurity. Palm plantations in the Ouémé Valley, and more generally all land purchased in peri-urban areas, are thus equipped with cement pillars, and panels indicating the name and telephone number of the owner, in the hope of avoiding having the plot taken over by others.Footnote 9

While lack of staff plays a role,Footnote 10 the weaknesses of untitled land management by communes come first from the fact that the state has never structured and supervised it. In practice, the land law only deals with titled land and the process of immatriculation. Untitled land (customary land, but also plots in housing estates having housing permits) is left to these commune-level semi-formal procedures. However, at the same time, the state recognises them: administrative certificates and endorsed land sales contracts are part of the necessary documents for requesting a land title. By acknowledging them, and even more so by leaving citizens’ needs in terms of securing unregistered land without a political and institutional response, the state endorses these practices.

As access to a title is in practice impossible for most citizens, these procedures are the only way by which most interested citizens – mainly urban or peri-urban – can obtain official documents attesting to their land rights. They can be seen as ‘palliative solutions’ that attempt to provide practical responses to the problems encountered, given the shortcomings of public services. As stated by Olivier de Sardan (Reference Olivier de Sardan2014), those behaviours are ‘unofficial’, ‘out of step with what the texts provide’, ‘at the limit of legality’ (and sometimes even illegal), but they provide informal solutions to bottlenecks in public services.

2 Land Markets, Conflicts, and Insecurity: A High Regional Diversity

In 2007, 40 per cent of plots of land in urban areas, and 10–13 per cent in rural areas, have been purchased (INSAE, 2009, p. 165). However, only 5 per cent of individuals have a land title in urban areas and 0.8 per cent in rural areas (INSAE, 2009, p. 106). In 2011, 6.6 per cent of plots had a housing permit and 44.4 per cent had a sale agreement from the town hall. In Cotonou, 72.0 per cent of individuals who own a plot of land have a sale agreement from the commune and 7.5 per cent a land title (INSAE, 2012, p. 53). The proportion of loan amounts secured by a land title is very low (1 per cent at most; Steward International, 2010, p. ix).

Legal uncertainty is widespread, due to an absence of legal documents or to poorly managed land information. However, this does not impede land transactions. Land markets are absent in most rural areas, but they are common in urban and peri-urban contexts, as well as in countryside in the south.Footnote 11 Moreover, it does not always translate into real insecurity, or into a proven risk. Informality does not mean insecurity as long as land rights are not contested and legitimate authorities are able to solve conflicts. Insecurity and conflicts are concentrated in some areas, some configurations, and for the least powerful actors.

In the cities, a large part of the territory has been subdivided for housing, people’s rights on the plot they live on are quite stabilised by occupation, and the inhabitants frequently hold one or more documents: residence permits, sales agreements, and administrative certificates. Cases of conflicts or insecurity arise due to contradictory overlapping rights, or conflicts over inheritance or sales. Some houses in cities are marked ‘contentious, not to be sold’. Family rights holders may contest sales made without their consent, even a long time after the fact. Sellers’ heirs can even go to trial when they see that the value of land has dramatically increased and they can win in court. In some cases, buildings have to be destroyed because of a court decision, due to a conflict relating to a sale, but there are few reliable data on the number of such cases.

Conflicts frequently involve disputes over past sales, or inheritance disputes. Family houses are occupied by different family members and the eldest son often takes responsibility for them upon the father’s death, postponing the distribution among the heirs. He manages the income from the rented property for his benefit. The youngest, and especially women, are increasingly claiming their share of inheritance, based on the recent Family Code (2004), and are less hesitant to go to court, which has led to an increase in the number of such cases (Andreetta, Reference Andreetta2019).

In rural areas, land governance is largely by customary or neo-customaryFootnote 12 norms and by ‘traditional’ authorities, whose power varies greatly from one area to another, with the intervention of state agents and the territorial administration or municipal elected officials in the event of conflicts. Depending on the region, population density and land-use patterns, land tenure relationships are more or less individualised. The contrast is striking between the southern regions (Mongbo, Reference Mongbo, Longbottom and Toulmin2002) – densely populated, highly individualised, where an inter-farmer land market for purchase and sale has existed for a long time – and the rest of the country, where such a market is non-existent or almost non-existent. Urban buyers, with financial resources that are disproportionate to those of rural families, are one of the major factors in the commodification of land, in – sometimes even remote – peri-urban areas, along roads and in pioneering areas, where land is still available. Sales contracts are sometimes based on a mutual agreement, but can also rely on corruption, manipulation, or even force (Kapgen, Reference Kapgen2012).

Investing in land is indeed one of the preferred strategies of urban elites and the middle classes. This rush on land fuels acute land speculation, which is felt far inland. All those who can afford it buy plots of land on the periphery or in remote suburban areas according to the available opportunities and their financial means. ‘Land mafias’ expand around large cities, which bring together landowners’ lineages and ‘canvassers’, surveyors, and municipal or state agents. Multiple sales of the same plot of land, and contestation of former sales by rights holders (shortly after a sale made without their knowledge, or years or even a generation later when they discover that the plot’s value has increased significantly) are frequent, causing insecurity for buyers. Nevertheless, these buyers rush to take advantage of all opportunities, hoping to secure at least part of the plots they buy.

Numerous actors highlight the high prevalence of land conflicts. However, solid figures are rare. Existing surveys are often ambiguous in their definitions of conflicts.Footnote 13 In 2007, a survey shows that the proportion of plots that have been the subject to a dispute is 1.4 per cent in urban areas and 1.1 per cent in rural areas, which is considered ‘a low proportion’ (INSAE, 2009, pp. 169–70), but the difference in figures between 2006 and 2007 is astonishing. The percentage of conflicts is highest in the urban and peri-urban departments of the south of the country (around 4 per cent) and very low elsewhere (less than 1 per cent). Numerous communes in rural areas recorded no land conflicts in 2007.

Contestation of property rights (inheritance, land sales, land grabbing) is the most frequent source of conflict (33.9 per cent; INSAE, 2012, p. 122).Footnote 14 Plots of land with a written document are less prone to conflict, but the title does not provide much more of a guarantee than other documents. Land conflicts affected 3.4 per cent of plots with no administrative documents, against 2.7 per cent for plots with a non-formal sales agreement, 2.4 per cent with a sales agreement established by municipal authorities, 2.3 per cent with a residence permit, and 2.0 per cent of plots with a land title (INSAE, 2012, p. 121). Having a document reduces the risk of conflicts, but a land title does not provide complete security.

These data show clearly that conflicts are more frequent in urban and peri-urban contexts. There is no direct link between informality and conflict, and a land title is not much more secure than a sales agreement issued by a commune. Most conflicts are solved outside courts and at a lower cost. Only 12 per cent of property rights disputes are settled by the courts (INSAE, 2012, p. 130). Most of them are solved at family level (26 per cent), at commune level (25 per cent), and at village or subcommune level (24 per cent).

3 Institutional Bottlenecks before Reforms: Vested Interests in Confusion

We can summarise the situation at the end of the 1990s as in Table 7.1, proposed by the research project.

Table 7.1 Institutional bottlenecks

| Deep factors | Proximate causes | Identified weaknesses | Economic consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plurality of social and land norms within society | Obsolete legal texts | Legal recognition of land rights inaccessible to the vast majority of the population | Importance of informality |

| Normative conception of the law, not seen as being in the service of the society | Unregulated legal duality between state law and neo-customary norms | Registration procedure that does not guarantee reliable publicity and protection of existing rights | Conflicts, especially in peri-urban areas |

| No affordable solution for ordinary people | |||

| Conception of ownership as ‘absolute’ and given by the state, ‘from the top’ | Centralised land tenure administration | Unorganised plurality of state and neo-customary bodies in land governance and conflict resolution | Spoliations, in particular in land subdivisions and plots of land purchases |

| Colonial legal framework, left in place without major change since independence | Expensive procedures for having a land title | Poor reliability of ‘semi-formal institutions’ | Transaction costs in land purchases |

| Multiple interests in ‘confusion management’ | Duplicate procedures and rent-seeking strategies by land administrations and professionals | Unsecured sales (for family rights holders and for buyers) | Cost of conflict for households and businesses |

| Rent-seeking financial system | Semi-formal palliative institutions | Little/no access to credit for rural producers, nor in the case of urgent need | Distress sales |

| Shortcomings in the supply of credit to rural people | No taxation on purchased land not valued | Unproductive or speculative | |

| Accumulation by elites |

Some forty years after independence, land governance is still based on the colonial duality between private titles for land and informal or semi-formal plots. Most of the country’s plots are governed following customary or semi-formal procedures at commune level. Instead of designing sound commune-level procedures to make them more reliable, and answer to the needs of the majority of citizens, government has allowed them to develop unchecked, leaving gaps for manipulation and power grabs. For Piermay (Reference Piermay1986, Reference Piermay, Frelin and Haubert1992), who studied urban land practices in central Africa, and Mathieu (Reference Mathieu and de Villers1996), who was interested in the rural situation in Sahelian Africa, the situation of informality and vagueness about the land rules does not result from chance. It is the product of a deliberate strategy of ‘managing confusion’ by political and administrative elites, who are well integrated into the political and administrative networks and able to take advantage of it.Footnote 15 The situation of Benin confirms this analysis. The obsolete nature of the texts, the vagueness of the rules, the institutional shortcomings, the complex procedures, the lack of resources for the administrations are greatly responsible for the current situation. These institutional deficiencies are partly the product of a lack of interest – and budgeting – on the part of the state. Constraints on human and financial resources in state administration bodies have been aggravated by structural adjustment.Footnote 16 However, their maintenance over time cannot be attributed solely to negligence and it is advantageous for certain parties. Informality in rural and peri-urban land allows urban dwellers to buy it at a cheap price; the lack of updating of the state property register and the obsolescence of the state land transfer scale clearly favour the grabbing of the state’s domain by actors who know the rules and have relations with land administration agents; land title registers are not maintained properly, which allows for manipulation.

Land subdivisions are a privileged place for land corruption (Aboudou et al., Reference Aboudou, Joecker and Nica2003; Kakai, Reference Kakai2014, pp. 16–18). Surveyors apply an exaggerated ‘reduction coefficient’ that allows them to illegally create new plots that they share with local elected officials. The heads of communal land services and elected officials are also involved in land speculation. The ministry for urbanism states that ‘some land canvassers maintain a land mafia which sometimes leads to the counterfeiting of Land acts with the complicity of the Land affairs services of the Mayor Office’ (MUHRFLEC, 2011b, p. 58). These deficiencies and the lack of resources open up many opportunities for negotiation, privatisation, and informal transactions, and even manipulation or corruption. As Bayart (Reference Bayart1993) explained thirty years ago, in Africa land and property ownership is the wealth par excellence and the main source of accumulation for national and local politicians, and state agents and the institutional shortcomings do not only result in losers.

B Adaptation versus Replacement: Competing Attempts at ReformFootnote 17

1 The Emergence of the Debate on Land Security in the 1990s

In Benin, the first seminar on housing and land tenure security, in 1984, is regularly quoted as the starting point for further reflection. But it was only around 1990 that the spoliations linked to a collapsing revolutionary regime, the land grabbing by the elite on the private domain of the state, and the abuses by state agents against the population led to the state’s land monopoly being called into question (Gbaguidi, Reference Gbaguidi1997). The context was one of economic liberalisation and democratic transition. Land rights’ informality and tenure insecurity started to be raised as a problem, in both urban (Comby, Reference Comby1998b) and rural areas (Hounkpodoté, Reference Hounkpodoté, Toulmin, Lavigne Delville and Traoré2002). In both contexts, the issue was to favour wide access to legal recognition and to prevent land conflicts. Several reform projects were raised in different ministries.

2 In Urban Areas, Tool for Commune-Level Land Taxation and Unsuccessful Discussions on Legal Reform

In the early 1990s, the French cooperation set up local land taxation tools, called Registres Fonciers Urbains (RFUs – urban land registers), in Cotonou and Parakou (Charles-Dominé, Reference Charles-Dominé2012). An RFU consists in a map of land occupations – regardless of their legal status – built from field surveys, allowing the issue of tax notices. The RFU allows a significant increase in tax resources, but remains incompletely mobilised by the municipalities, both because elected officials are reluctant to increase the pressure to pay taxes, and because of weak institutional anchoring in the municipalities’ administrative system (Simonneau, Reference Simonneau2015). RFUs have then been disseminated to other municipalities, by various donors, in various forms and with limited success (Simonneau, Reference Simonneau2015). While RFUs are primarily a fiscal tool, their designers thought they could help to register ownership: the presence on a plot for a sufficient period, as evidenced by the regular payment of property tax, could be considered after a given number of years as a proof of ownership, avoiding the complexity of immatriculation.

As part of the Urban Rehabilitation and Management Project (Projet de Gestion et de Réhabilitation Urbaine [PGRU], with World Bank financing), a series of studies conducted in the 1990s laid the groundwork for possible land reform. Comby (Reference Comby1998b) identified four possible strategies. The first was ‘an improvement of practices and reorganization of administrative means in compliance with existing law’. The second was ‘a policy of occasional improvements leading to a significant improvement’. The third built on the development of group registrations. The last strategy was based on deep modification of the conception of ownership and land rights legalisation: ‘in a more radical break with current legal and administrative practices, making ownership a matter to be settled between private persons. The State and its administrations no longer deal with the recognition and allocation of property. The peaceful owner of a piece of land is presumed to be the owner, with the burden of proof to any interested person to the contrary by taking legal action’ (Comby (Reference Comby1998b, p. 17). This would mean abandoning the colonial conception of state-guaranteed land ownership in favour of a contractual approach, like in the French Civil Code.

‘For many people’, according to Comby (Reference Comby1998b, p. 17), ‘all the current difficulties stem simply from a lack of respect for existing texts. They think that it is not the law that needs to be changed, but that it is the practices that must be brought into conformity with the law, all the evil coming from the fact that the law was no longer respected’. However, this expert supported the ‘bottom-up ownership’ perspective and thus an exit from the standard registration model. He explained that the scenario for implementing existing law was doubly unworkable: first, it would imply being able to prohibit sales of unregistered land, and then the cost and pace of issuing land titles are incompatible with a desire to address the problem on a significant scale.

Prepared by Beninese experts, the collection of legal texts compiled for the PGRU (SERHAU, 1999) timidly opens the question of alternatives to land titles, or in any case significant changes in procedures: ‘It may be necessary to study at the State level how to make it accessible to as many people as possible and if it must always be maintained as the mother of evidence of land ownership […]. There is a need to simplify the procedure along the lines of the procedure for establishing customary land rights […] and to restore the contract as an essential role in the acquisition of property’ (SERHAU, 1999, p. 350, emphasis added).

In practice, however, it is the first scenario that the Beninese authorities adopted, with the establishment in 2001 of a ‘Commission for the transformation of housing permits into land titles’, which was supposed to accelerate the issuance of land titles. The ‘Land and residential security’ programme driven by the Ministry for Urban Planning planned to issue 45,000 land titles between 2005 and 2007 (Le Meur, Reference Le Meur2008, p. 10). Blocked by complex procedures and by the entry of land professionals raising bids on procedures, this has been quite ineffective (see later). At the same time, the Ministry of Urban Planning launched a reflection on a possible reform of land and urban planning.

3 In Rural Areas, the PFRs and the Draft Rural Land Law: The Search for an Alternative to Land Title

In rural areas, two successive development projects, under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and with French and German funding,Footnote 18 have integrated the issue of land tenure security, first as a tool for encouraging farmers to invest in anti-erosion techniques. The project began in 1992 and experimented in different regions in the country with the Plan Foncier Rural (PFR) approach, imported from Côte d’Ivoire, where it had been invented a few years earlier (Chauveau et al., Reference Chauveau, Bosc, Pescay and Lavigne Delville1998; Gastaldi, Reference Gastaldi and Lavigne Delville1998).

In the PFR approach, land rights are identified through cross-checked field surveys, conducted on a plot-by-plot basis. Each plot holder explains the rights he or she has and how – and from whom – he or she has obtained them. The boundaries of the plots are measured with a decametre and then drawn on an aerial photo.Footnote 19 Two types of situations are considered: those of individual owners (‘presumed owners’ in legal language) and those of family communities, represented by their ‘manager’, in other words the representative of the group of rights holders, who has authority to make decisions on the plot in question. The plot holder and the holders of the neighbouring plots sign the survey report. After a publicity phase, which is supposed to allow everyone to verify or correct the collected information, the final plot map and rights-holders’ register are given to the village committee, which is supposed to register future changes in rights (inheritances, sales, leases, etc.) and to keep the land documentation up to date. PFR is thus a kind of village land cadastre, without legal value. However, in the idea of its promoters, the demonstration that it is possible to map ‘informal’ customary rights, which are often considered difficult to understand from the outside, should contribute to promoting a legal reform. This reform could create a new and more appropriate legal status for rural land and thus enable rural actors to obtain legal recognition of their rights.Footnote 20 Some forty pilot PFRs have been carried out in two successive projects in different regions of the country, which allowed the methodology to be put to the test and to be improved. However, the idea of a coherent village territory constituted of juxtaposed farmers’ plots is a simplification. It does not really consider the diversity of customary land rights (CIRAD-TERA, 1998); pastoral rights, commons, and agricultural areas where land rights are not stabilised (Edja et al., Reference Edja, Le Meur and Lavigne Delville2003) are not taken into account.

Present from the outset, the legal reform was put on the agenda in 1998 when a second project was negotiated between the Ministry for Agriculture and donors. Working under the supervision of several ministries (agriculture, justice, economy), a group of Beninese experts (lawyers, anthropologists, economists) drafted a law that was a potential legal revolution: it renounces the presumption of state ownership of unregistered land and provides that every plot subject to ‘rights established or acquired according to custom and, more generally, local practices and standards’ (art. 7) is part of private land. The draft law institutionalises PFRs and gives them, as an outcome, a new legal document, the CFR (certificate foncier rural, rural land certificate). A CFR is a ‘document of recognition and confirmation of land rights established or acquired according to custom or local practices and norms’ (art. 111). It can be individual or collective, it is transferable, assignable, and usable as collateral for credit (arts. 9 and 112). ‘A presumption of acquired rights is attached to it as proof until proven otherwise, established before the judge’ (art. 111).

In line with the recent administrative reforms creating elected local governments (1999), the draft law sets up a local land management framework, anchored in the communes and integrating village-level bodies. Communes deliver land certificates for plots registered in the PFR and maintain land information. Villages benefit from PFRs at their request and can define their own rules for managing natural resources on their territories. All transfers of land rights must be formalised at the village level, and permanent transfers (sales, heritage) have to be recorded at commune level, so that new certificates can be issued.

This reform clearly relies on an ‘adaptation’ paradigm. It rests on a legal innovation, thought to be more fitted to rural areas and much cheaper. The objective is to expand PFRs and thus land certificates with a progressive approach, relying on villages’ demand. Meanwhile, the institutional framework at commune and village level has to be put in place everywhere, to allow for local registration of land transfers even without PFR. The land certificate can be transformed into a land title but, for its promoters, most farmers will stay with a land certificate, which answers to their needs and is supposed to become dominant. With that draft law, new land legal and management frameworks are proposed for rural areas, alongside the land title and the state land administration.

The paradox is that this ambitious reform is made of a policy tool, the PFR, and a law, without a policy statement stating its objectives. It benefits from a relative consensus in MAEP (the Ministry of Agriculture, Herding and Fishing, where some actors support agribusiness and land titling) and more generally among the actors involved in the rural zones and decentralisation policies. Nevertheless, it faces opposition from actors in the Ministry of Urban Planning: for them, specifically rural legislation makes no sense and raises insoluble problems at the boundaries between rural and peri-urban areas; CFR can only be an intermediate document, of much lower status than the land title, and is contradictory to the provisions of the Organisation pour l’Harmonisation en Afrique du Droit des Affaires (OHADA, Organisation for Harmonising Business Law in Africa), which provides (art. 119) that only the land title (or failing that, an ongoing application) is recognised as the basis for a mortgage.

Partly because no policy statement defines the vision, different conceptions of the reform coexist. For its promoters, it creates a long-term alternative to land titles, allowing rural dwellers to have access to legal recognition of their rights. Among them, some want to quickly generalise PFRs over the country, while others prefer a more progressive strategy for expansion, depending on means and needs, starting from areas where PFRs are most useful (Lavigne Delville, Reference Lavigne Delville, Colin, Le Meur and Léonard2009). For those who support classic land titling, PFR is only a temporary framework, and land certificates must quickly be transformed into titles. The diversity of policy options that PFR can serve helps to build adhesion around it.

Ready since 2002, the ‘law on rural land tenure’ was initially blocked by the MCA team. It was finally passed in 2007 with MCA support. In the meantime, an action plan for implementation had been designed, which proposed a progressive strategy under the aegis of an Agency for Rural Land Tenure Management, to be created to take charge of coordination, technical support to communes, and management of a multidonor fund.

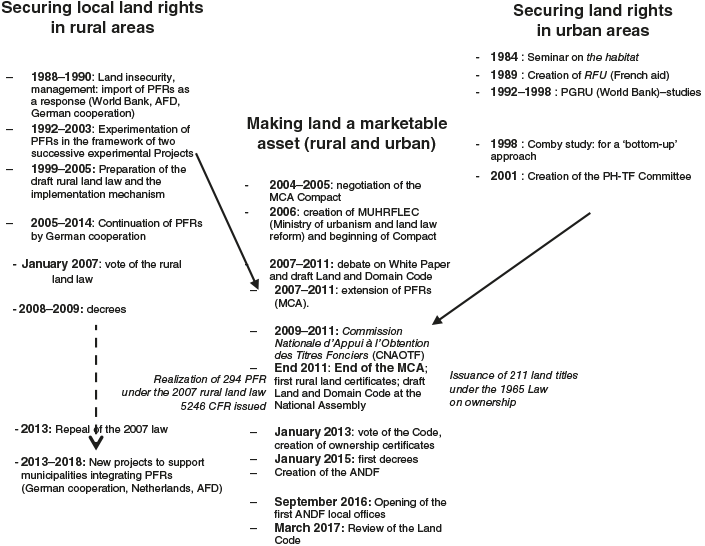

4 In the Mid-2000s: The MCA-Benin and the Emergence of a Global Reform Project

In the mid-2000s two separate policies were thus ongoing (Figure 7.1): in urban areas, the Committee for Transforming Housing Permits, which was practically ineffective (see Section II.B.2), and in rural areas, the PFRs, a draft law on which was ready (see Section II.B.3). A new initiative emerged at that time, carried out by the MCA-Benin, with a view to harmonising land law at the national level. Following the 2004 Monterrey Conference on aid funding, the US government created the MCC to support economic development projects proposed by beneficiary countries, officially selected based on good governance criteria. Benin was among the first countries selected. Its government set up a series of workshops to identify the themes around which to build a proposal. Land issues emerged from discussions between the government and the MCC. The Compact was signed in 2006 and implementation took place between 2007 and 2011. The Compact’s ‘Access to Land’ project aimed at overcoming the divide between rural and urban and promoting a global land reform, making access to land title easier and cheaper (Figure 7.1). It had two components: at institutional level, a legal reform that aims to standardise land law, overcome legal dualism, and provide the country with updated legislation; at operational level, field projects were supposed to scale up previous initiatives, in both rural and urban areas. Positioned under the aegis of the Presidency of the Republic, the MCA was the central actor, and the centre for the design and preparation of the land reform. In 2007, shortly after the launch of the Compact, the new President of the Republic, Boni Yayi, officially placed responsibility for land reform under the aegis of the Ministry of Urban Planning. These two bodies have steered the reform.

Figure 7.1 Chronology of land reforms in Benin.

The MCA project has been clearly oriented towards the promotion of land titling. During its formulation, the fight has been fierce between the Ministry for Agriculture, defending the PFR and the draft Rural Land Law, and MCA and the Ministry of Urban Planning, claiming leadership of the global reform and wanting to use PFRs as a tool for issuing land titles. Having high-level political support and a strong budget, the MCA reform took the lead after 2006 and signature of the Compact.

Several initiatives towards land reform emerged in Benin in the 1990s–2000s, from several ministries and with the support of different donors (Figure 7.1). All of them tried to answer the issues of informality and insecurity in a context of economic liberalisation and democratic transitions. All relate to what Muller (Reference Muller1990) calls a global/sectoral adjustment: a situation where a given policy sector, built and organised in coherence with a former global policy paradigm, has to adapt to a change in this paradigm, because its vision, tools, and institutions are now outdated. These competing reform projects were all attempts to adjust the land policy and administration to the liberalisation of the economy and to the democratic turn. However, the answers were different, illustrating the contrast between replacement and adaptation paradigms.

In rural areas, titling is almost non-existent, individual ownership is not the rule and most land is held by family groups, and the value of land does not justify supporting the high costs of titling. Specialists in rural areas promoted adaptative strategies, based on a new land administration and new legal documents, to allow for cheaper, affordable access to legal recognition of individual or collective land rights. While the centrality of the land title has been timidly questioned in urban areas, and the shortcomings of classic strategies for developing access to law have been explained by World Bank experts, state bodies clearly chose to push to titling.

III Expanding Access To Land Title Through a Deep Reform of Land Administration: The MCA-Benin-Led Reform (2006–2018)

A ‘Making Land a Marketable Asset’: MCA-Benin and Its ‘Access to Land’ Project (2006–2011)

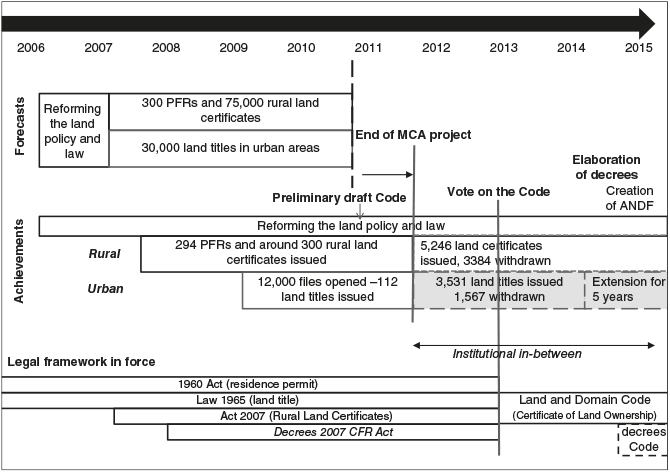

With a budget of about US$30 million, out of the US$350 million in the Compact, the MCA Access to Land project had the stated objective of ‘making land a marketable asset’, consistent with a vision of the land issue in terms of economy, or in any case with the MCC’s priorities: ‘The aim is to facilitate access to land ownership for the greatest number of people, to remove people from land insecurity by formally registering them, to increase their capacity to access credit and to stop the “slumming” of urban centres that have become areas for receiving massive flows of rural people in search of better living conditions’ (République du Bénin, 2004, p. 4). The reform aims at making access to land title faster (one year against three or more) and cheaper (CFA Franc 100,000 – €150 – instead of a minimum of CFA Franc 300,000 – €450).

In five years, the project wanted to (1) reform land legislation to modernise and standardise it; (2) implement 300 village-level PFRs, issue 80,000 rural land certificates (CFRs), and transform 75,000 CFRs into land titles;Footnote 21 and (3) reform the ‘Commission for the transformation of housing permits into land titles’ and issue 30,000 urban land titles. With its significant resources and its tight timetable, the Compact was for its promoters an opportunity to fight against conservatism, force institutional reforms, and finally make it possible to get rid of informality. The initial schedule of the Land Project provided for the first year to be devoted to land reform, after which the operational components would be implemented in a clarified framework during the following four years. This tight timeframe has been largely overwhelmed.

1 The Institutional Component: Updating the Land Law and Negotiating the Agencification of Land Administration

While the will to reform the land administration was clear, the institutional vision was not yet designed at the beginning. The MCA team recruited an American consulting firm specialising in the sale of technological solutions for the legal security of land transfers to manage the process. The relationship between the MCA and the firm has been stormy, due to conflicts of vision. The diagnosis made (on conflicts, land speculation, women’s access to land) did not take into account current economic and social science results or field studies (Edja, Reference Edja, Bierschenk, Le Meur and von Oppen1996, Reference Edja2001; Mongbo, Reference Mongbo, Longbottom and Toulmin2002; Le Meur, Reference Le Meur2006; Magnon, Reference Magnon2013). It was based on the standard but biased assumptions that customary laws were outdated, and that informality was the source of the problems. The diagnosis partly included the misdeeds of surveyors during housing developments, the monopolisation of the private domain of the state by the elites, and the absence of regulation and supervision of real estate agents. Nevertheless, the operational strategies then took little account of these problems, and seemed to consider that legal and organisational change would suffice to prevent them in the future.

State bodies and professionals involved in land management (surveyors, notaries) were involved in the ‘participatory’ process of policy formulation, civil society organisations, scholars, and other resource people being largely put aside. Debates between interest groups, state structures, and professional corporations were lively. While the initial principle had been to reform the DDET and push for creating local offices, DDET strongly resisted this to keep centralised control over titling. To overcome this blockage, the study on the institutional framework suggested in 2009 a more ambitious reform, with the creation of a National Agency for Land and Domain taking over a set of functions previously carried out by different technical departments spread over several ministries, and issuing and managing land titles, though local offices. Agencification is supposed to bring more professionalism, efficiency, and transparency in land administration.

The white paper (MUHRFLEC, 2011b) was adopted and translated into a policy document (MUHRFLEC, 2011a), itself adopted in June 2011. At the end of the contract with the consulting firm, only a first draft of the Code had been written. The process was then taken up directly by the MCA team, which enabled finalising a draft Code that was finally voted on in January 2013.

2 The Operational Component: Trying to Deliver Legal Documents at a Large Scale

Field operations were supposed to take place after the legal reform. In practice, both took place simultaneously, which led to institutional contradictions, in particular for PFRs. The progress and difficulties that MCA’s operations faced in the field highlight the practical and managerial issues of land rights registration, shedding light on issues that the reform’s implementation will also face.

PFRs and Land Certificates: Institutional Contradictions, Implementation in a Hurry, and a Sudden Ending

The Land Project aimed to create PFRs in 300 villages, covering around one-tenth of Benin. Due to delays in the land legislation component, it was implemented under the 2007 law that had just been enacted and not under the Code in preparation. This led to different biases in the implementation process. The MCA could not rely on a national body for the implementation of PFRs; by mutual agreement, it contracted a consulting firm. Moreover, the MCA team did not support the commune-level institutional framework created by the 2007 Rural Land Law and had little interest in its effectiveness and sustainability. While the existence of a sustainable system for the administration of registered rights is a prerequisite for the sustainability of land rights formalisation operations, the project put the emphasis on the production of maps and registers and the issuance of CFRs, in a non-stabilised institutional framework.

In the pilot PFRs, the priority for field operations was the legitimacy of registered rights. The firms leading the process were committed to sociological surveys, the surveyors being subcontractors. During the tenders for the implementation of PFRs in the villages, the surveyors’ firms claimed to be the leaders of the consortia. They won after a year of struggle, which had consequences for the quality of land rights surveys, which were considered secondary compared to delimitation. The high quantitative ambition in a few years also had many impacts on the quality of the work, by multiplying inexperienced teams, who had to complete the work in a limited time. Moreover, the coordination team did not carry out any real training and support work for the field teams they hired, in order to help them overcome the problems they encountered. While identifying land rights is subtle work, they did not exercise any quality control, leaving the investigations to be carried out by teams of varying quality and sensitivity. The record of rights was heterogeneous depending on the teams, which sometimes pushed for collective registration to limit the number of plots to survey, and sometimes pushed to register individual use rights, even within households. The state public domain has not always been identified in the maps, with the risk of re-creating legal confusion. Almost everywhere, teams could not survey the full village territory, due to conflicts – particularly but not only between migrants and indigenous people (Lavigne Delville and Moalic, Reference Lavigne Delville and Moalic2019) – as well as absentee owners, refusal to survey uncultivated areas, lack of time, and so on. These biases, errors, and problems resulted from a vision of PFRs that underestimated the issues and difficulties of registering customary rights. This is surprising because part of the field teams had already experienced some of these difficulties during the pilot phase, but lessons were not learned.Footnote 22

The first rural land certificates were issued in a hurry, in mid-2011, just before the end of the project, mainly to allow the MCA to say that the process had begun. At the end of the contract, in 2011, 294 PFRs had been carried out of the 300 planned. Many had incomplete surveys and more or less numerous errors. The software for managing tenure information was not fully working. Village committees and communal services were left alone without support for learning and developing experience. Some adopted a wait-and-see attitude, while others tried to conduct their work as best as they could. A new heterogeneity emerged, linked to local land tenure configurations, the interest shown by communal authorities and heads of communal services in land issues, and their capacity and initiative.

An econometric study of the impact of PFRs (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Houngbedji, Kondylis, O’Sullivan and Selod2018) nevertheless identified impacts. Even without certification, land demarcation activities caused a 28 per cent increase in the proportion of plots with clear borders among male-headed households (which is significant but relatively low for a systematic plot bornage); and plots registered to PFR are 2.4 percentage points more likely than control parcels to be used primarily for perennial crops. However, no impact is seen on farm yields or input use. One year after the end of the MCA project, an MCA survey noted ‘very poor results’ (MCA-Benin/Unité de Formulation et de Coordination, 2013, p. 4). Only 25 of the 40 communes with PFRs used the land information system that had been set up; only 5,246 certificates had been issued (7.2 per cent of the 72,742 expected) and only 3,527 had been withdrawn (4.8 per cent).

The delivery of CFRs was slowed down by enduring hardware problems that in some cases hid the reluctance of communes with regard to PFRs and their management. Communes had not really been involved in the decision to create PFRs on their territory. Their priority was urban land and housing allotments. Taxes on sales, which are an important part of local revenue, were called into question by the PFR system, which provided for sales contracts to be drawn up at village level. Finally, several commune officials were concerned about their future capacity to negotiate land in villages for public infrastructure: if plots had land certificates, would the villagers still agree to freely give land to the commune for building a school? If land had to be purchased or expropriated by the commune, the cost of investments would increase.

As a result of pressures from the MCA Coordination Unit, the number of CFRs issued and delivered increased, at a very heterogeneous pace depending on local issues. However, their future was uncertain as they were recognised in the Code, but with a low legal value, equivalent to the old administrative certificates.

Transforming Housing Permits Into Land Title: A Stalemate

In urban areas, the objective was to accelerate the transformation of residential permits into land titles. The pilot operation carried out in Cotonou and Porto Novo had issued only 1,483 titles in three years, including 292 in the name of the state and 1,191 in the name of land interest associations, bringing together the owners of housing land. By July 2006 only 110 beneficiaries had withdrawn their title (Lassissi, Reference Lassissi2006). The Land Access Project restructured the National Commission and provided it with substantial financial resources. A new Commission Nationale d’Appui à l’Obtention des Titres Fonciers (CNAO-TF, National Support Committee for the Acquisition of Land Titles) was created in February 2009 and began its work in June 2009. The first land titles were delivered in June 2011, six months before the end of the MCA project. At the end of 2011, more than 10,000 cases had been initiated but only 211 titles issued. After the end of MCA funding, the Commission continued operating, with reduced resources coming from the national budget. By August 2014, 3,531 titles had been issued, of which only 1,567 had been withdrawn by their holder (including 1,190 for the city of Cotonou alone).Footnote 23

The restructuring of the Commission and the amount of resources mobilised have therefore only partially improved its productivity, which remains marked by a low demand, a complexity of procedures requiring the intervention of multiple actors, and great difficulties in gathering legal evidence, even on housing allotments made by the state. Created for an initial period of five years, the CNAO-TF was extended in 2014 for another five years, with a target of 3,000 titles per year, too small to reach the initial MCA target in ten years, and in any case largely insufficient to move urban land out of the informal sector. After the establishment of the ANDF in 2016, the CNAO-TF was shut down and its files were transferred to its decentralised offices.

In rural as well as urban contexts, the important MCA funding proved unable to significantly enhance the delivery of legal land documents. In urban areas, institutional bottlenecks linked to the participation of notaries and surveyors, as well as the complexity of meeting the legal requirements, have bogged down the process and the very small number of land titles withdrawn raises questions about people’s interest. In rural areas, contracting with firms allowed the target of 300 PFRs to be reached, at the cost of low quality but above all a lack of institutional anchoring. Very few land certificates had been issued at the end of the project.

3 After the End of the MCA Project (2012–2015): Uncertainties, Reconfiguration, and the Vote on the Code

At the end of the MCA project, the planned major reorganisation of land management had only been initiated. A geodetic station system had been set up. A preliminary draft Code had been drafted, but did not seem at that time to have strong political support and its adoption was uncertain. The delivery of titles and certificates fell far short of the targets. The rural land management system had been put in place in forty of the seventy-seven communes, but its future remained largely uncertain, and the whole system was in danger of rapidly collapsing due to a lack of institutional consolidation. The MCA team, which carried out all of these actions, had been dispersed. However, the reform process continued with the vote on the Land Code in early 2013, the redaction of the decrees in 2015, and the creation of ANDF in 2016.

Finalisation and Voting on the Land and Domain Code (2012)

The legal reform process went on after the end of the project. The lawyer in charge of it in the MCA team pushed on the work after the end of the Compact and tried to move the issue forward at the political level. Confronted with their desire to unify the legal framework and with strong criticism of standard registration and land title, the reformers eventually abandoned the term ‘land title’. They conceptualised the logic of the Code in terms of ‘confirmation of land rights’, with a twofold channel, that of individual demand (which barely modifies the standard registration procedure) and that of PFR, both resulting in a single private property document, the Land Ownership Certificate. No provision is made for collective processes in urban contexts. Unlike the land title, a Land Ownership Certificate can be challenged in court for a period of five years in the event of fraud or error.

A preliminary draft Code, a long text of 543 articles, was completed at the very end of the MCA project in 2011. It bore the imprint of the multiple expert meetings and controversies that marked it. Fearing that the Code would favour land grabbing, a young farmers’ union, Synergie Paysanne, gathered a dozen non-governmental organisations (NGOs) within an ‘Alliance for a consensual and socially just Land Code’. Faced with difficulties in accessing information and a certain lack of transparency in the process, the Alliance mobilised to impose itself at the table and try to influence it through public meetings and advocacy (Lavigne Delville and Saïah, Reference Lavigne Delville and Saïah2016). It unsuccessfully advocated for restrictions on land sales. The final draft Code was submitted to the National Assembly in 2012. The government was indeed facing an emergency, as new MCA financing was in sight (which would not work on land). For the government, enacting the Code was a proof of goodwill towards the MCC, in a context in which Benin was, for a time, criticised for corruption and could have lost the opportunity of a second Compact.

The vote on the Code occurred in January 2013. The text puts the future ANDF under the supervision of the ‘Ministry in charge of land’. However, no ministry at that time had land in its attributions. A strong inter-institutional struggle then opposed the Ministries of Finance (head of DDET) and of Urban Planning. The former highlighted the possible risks for land tax collection if land and cadastre were not under its responsibility and ultimately gained control of ANDF. The text was finally promulgated in August 2013, but by the end of September no signed version had been circulated and the various actors were still trying to verify if it had really been promulgated.

A Reconfiguration of International Support and Field Projects

The end of the MCA Compact led to a vacuum. Although not involved in land issues until that time, the Dutch Embassy agreed in 2012 to support a transitional phase, aimed at advancing the implementation of the recently adopted Code, through the preparation of implementing decrees and support to municipalities in the management of PFRs. It also supported the creation of an informal coordination group on land issues, bringing together donors, national institutions, NGOs, and farmers’ unions, to facilitate the exchange of information. This coordination group allowed for a certain institutional decompartmentalisation of the land sector, after the strong monopoly exercised by MCA.

As no national institution was at that time clearly in charge of the reform, the Embassy gave responsibility to the MCA Coordination Unit, the team coordinating the preparation of the new Compact, even though the land experts from the first phase had been dismissed and the second Compact would not work on land. In a phase of institutional vacuum, a MCA team with no legitimacy on land issues any longer was asked to prepare decrees. The legal expert recruited, who had been strongly involved in PFRs since the beginning, did important work in mediating and negotiating decrees, and in attempting to remedy a number of shortcomings in the Code. Fourteen decrees were prepared, which were promulgated in January 2015.

Support to municipalities in the management of PFRs only started at the end of 2014, after three years during which the PFR system, the commune land services, and the village committees were left alone. The consolidation project only in practice had time to refinance some equipment and run a series of training sessions and could not prevent the gradual collapse of PFRs.

During that period, several development projects, funded by the German Corperation for International Cooperation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, GIZ) and the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), continued to implement PFRs in their own areas. These projects had supported the initial design of PFRs as an alternative to land title and were concerned about the orientations of the Code. After the vote on the Code, they reviewed their approaches in the light of changes in the legal framework, and in particular the obligation to also survey residential areas. Finally, in parallel with supporting the preparation of the decrees and first contacts with ANDF, the Dutch cooperation financed a local land management project in two municipalities in the south of the country (2015–2018), in order to experiment with the reform and provide tools and methodologies. Conceived as projects to support decentralisation, these various projects promoted PFRs from a rural and communal point of view, and sought to negotiate modalities of implementation of the Code that were anchored in local contexts. They were in tension with the newly created ANDF, which was seeking to assert itself.

4 The Gradual Implementation of the New Institutional Framework (2016–2018)

The years 2016–2018 saw the establishment and ramping-up of ANDF, the repositioning of the various actors, and the beginning of the actual implementation of the Code. The amount of work done during these years is impressive. The institutional landscape became clearer after the adoption of the decrees in January 2015 and the attribution of ANDF’s supervision to the Ministry of Finance. The state then took charge of the deployment of the institutional mechanism provided for by the reform, which took place in a coherent manner. The Ministry of Finance reorganised itself, dissolving DDET and integrating ANDF into its organisational chart. An action plan for implementing ANDF was defined in July 2015 (Gandonou, Reference Gandonou2015). The lawyer who led the reform at the MCA level was recruited as general director. While ANDF is supposed to have offices in every one of the seventy-seven communes, fourteen ANDF local offices (one per department, plus one for Abomey-Calavi and Ouidah) were officially opened in September 2016.

President Talon’s coming to power in 2016 gave a boost to the reform. His programme (Bénin révélé) provides for a faster and cheaper transformation of housing permits to land title, the creation, of a national cadastre and the operationalisation of ANDF. President Talon ordered taxes on land registration to be lowered to make access to title cheaper. The committee for the cadastre was created in November 2016.

In May 2017, the Parliament passed a law (no. 2017–15) amending and supplementing the 2013 Code. At the same time, a digitisation project for land documentation was launched from April 2017, implemented by a French consultancy firm, which collected all land information (titles, supporting documents such as sales agreements or administrative certificates, plot maps of PFRs and housing allotments) to digitise them and integrate them into a single geographic information system (GIS). The spatial calibration of land titles was a huge task, since the references used by surveyors were heterogeneous. Land subdivisions were relatively easily repositioned on satellite images, but for individual titles it could be more complex. The team almost succeeded in positioning existing maps and titles in the GIS, but the information on landowners was still indicative, as the data were sometimes fake (in cases where only the planned resettlement plan exists, and not the final one) or obsolete due to changes, inheritances, transfers, or even fragmentation since the time the maps were drawn up. The consulting firm also had to validate the demarcation plans for new titles before integrating them into the GIS, which led them to reject many plans and force surveyors to do their work again. Field experiments for the implementation of the land cadastre in areas without land information were launched in early 2019, as part of Dutch support.

At the end of 2018, the institutional framework and its tools and procedures were more or less in place, apart from the cadastre. 47000 titles had been digitalised. ANDF had just over 200 agents, many more than the former DDET. Land documentation had been transferred almost entirely to the BCDFs. ANDF began issuing new land titles in April 2018Footnote 24 at a very slow pace (only 1,587 land titles were createdFootnote 25). Applications for new land titles were being processed, with a view to meeting the tight deadlines imposed by the Code. Pending applications were processed gradually.

In October 2018, Benin national mayors’ organisation (Association Nationale des Communes du Bénin, ANCB), with the support of the Projet Foncier local (local land management project), funded by the Netherlands, organised a National Workshop on Land to assess the situation. It established a progress report on the reform five years after the vote on the Code and allowed a dialogue between commune heads, ANDF, and the projects (Boughedada and Lavigne Delville, Reference Boughedada and Lavigne Delville2021). A new support project for ANDF, the Land Administration Modernisation Project, was launched in December 2018, also funded by the Netherlands.

B The Land Code, Its Provisions and Controversies

In this section I will describe the main provisions of the Code, and highlight some contradictions or loopholes. I will then explain the controversies that followed the vote and the main changes made by the 2017 revision.

1 The Main Orientations of the Code

The 2013 Land and Domain Code is an ambitious text that aims at radically reforming the legal and institutional framework of land tenure in Benin. It includes 543 articles, organised into 10 titles and 31 chapters. It explicitly repeals the 1965 Ownership Act, the 1960 Housing Permits Act, the 2007 Rural Land Tenure Act, and also, implicitly, the 1955 and 1956 decrees.

The Code updates the 1965–25 law on ownership, adding specific provisions from the 2007 Rural Land Law, and reorganising land administration around ANDF. Focusing on private ownership, the Code intends to break with legal dualism and standardise the law. It recognises a single title of ownership, the Land Ownership Certificate (Certificat de Propriété Foncière). This new name for what is fundamentally the classic land title is the result of a compromise between land title and CFR, and an answer to criticisms on the intangible, unassailable nature of land title, which allows dispossession and enables impunity even in the event of fraud or error. The Land Ownership Certificate is still intangible, but it temporally violates this principle by assuming that it can be contested in the event of fraud or error within one year after the discovery of the fraud (art. 146). However, any action lapses after five years from the date of establishment of the Land Ownership Certificate.

The Code follows the logic of the ‘confirmation of land rights’, with two ways of obtaining a Land Ownership Certificate. One is on an individual basis and follows the former standard procedure of registration, while improving local information. This process must respect a maximum duration of 120 days (art. 139). The other is collective, via the PFRs or collective confirmation processes (art. 142 ss), at the request of local authorities or a group of urban owners organised in a land interest association. The Code creates an Attestation de Détention Coutumière (ADC, Attestation of Customary Possession) for the rural environment, a new intermediate document issued by the local land management offices. In individual applications, this attestation, relocation certificates (obtained after land subdivisions for housing), and tax notices for the last three years can be used as ‘presumption of ownership’ documents to initiate the confirmation request. The recognition of tax notices as implying a ‘presumption of ownership’ is an important step towards the recognition of peaceful occupation as a source of ownership. However, sales agreements, housing permits, administrative certificates, and CFRs – that were until now the most accessible documents and the most used by citizens – are no longer recognised as documents allowing a person to apply for a Land Ownership Certificate.