Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

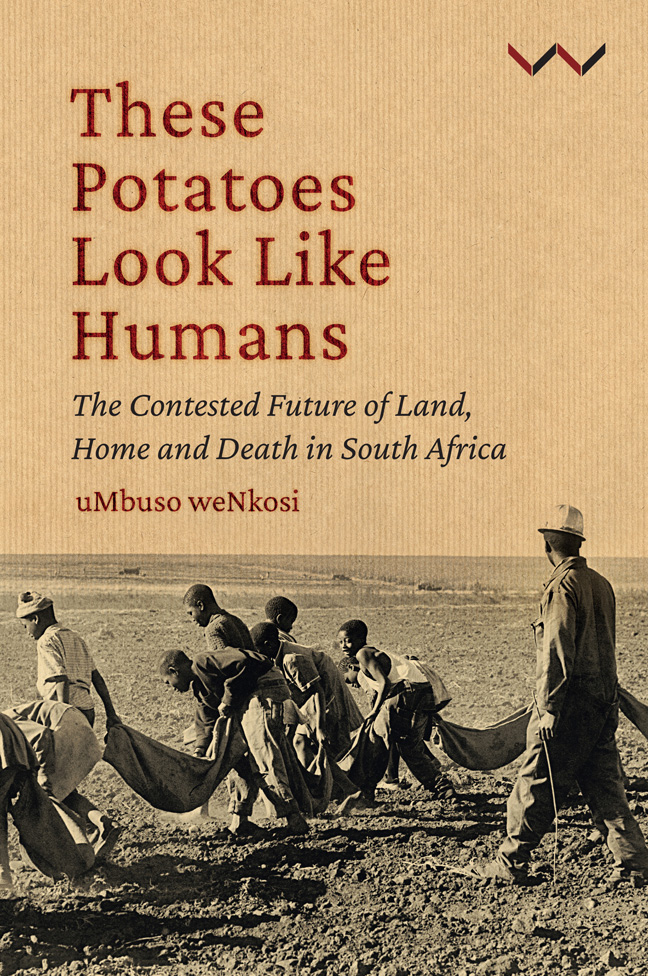

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

3 - Bethal, the house of God

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

When Jacob awoke from his sleep, he thought, ‘Surely the Lord is in this place, and I was not aware of it.’ He was afraid and said, ‘How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God; this is the gate of heaven.’

— Genesis 28:16–17The history of Bethal can be traced back to a donation of land made by two farmers, Cornelius Michiel du Plooij and Petrus Johannes Naudé, who intended to create a small town to serve the needs of the isolated farmers in the area. They named it after their wives, Elizabeth (Beth) du Plooij and Alida Naudé. Farming in Bethal relied on labour-intensive crops such as wheat, rye, maize and potatoes.

The private town was demarcated in 1868 in the south-eastern part of the farm Blesbokspruit. To the early settlers (Voortrekkers) in desperate need of a place for safe residence after they had been pushed out of Natal by the British occupation in 1843, the small town was seen as a holy place – they dubbed it ‘the abode of God’, after Bethel in Jacob's dream in the book of Genesis. George Hudson, colonial secretary at the time, published the proclamation of Bethal on 23 February 1898, making the town ‘subject to the administration, control and management of the Government of the Transvaal’.

Making a home and working in hell

The Bethal magisterial district incorporated the farms in the Standerton, Middelburg and Ermelo districts, with a surface area of 1 270 square miles and a total district population of 750 adult white men. There are no readily available demographic data for white women – and there is no mention of Black people existing in this area before the settlement of the white population, except as labourers. As whites settled in this district in the first half of the 1800s, they needed labour, and this led to an increase of Black people in the area.

During the Anglo-Boer War, Bethal was destroyed (see figure 3.1). On 20 May 1901, Boer women and children and Black labourers were driven from their houses to the outskirts of the town in open wagons, and the next day the town was set alight by the British soldiers. The townspeople watched as Bethal burned for two days, after which they were taken to concentration camps.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 51 - 76Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023