Book contents

- Trust in Early Modern International Political Thought, 1598–1713

- Ideas in Context

- Trust in Early Modern International Political Thought, 1598–1713

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Alberico Gentili (1552–1608)

- Chapter 2 Plans For Universal Peace in Europe – The Limits of a Balance of Power

- Chapter 3 Jus Naturae Et Gentium – The Limits of a Juridical Order

- Chapter 4 The Struggle for Hegemony and the Erosion of Trust

- Chapter 5 The Doux Commerce and Interstate Relations

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Ideas in Context

- References

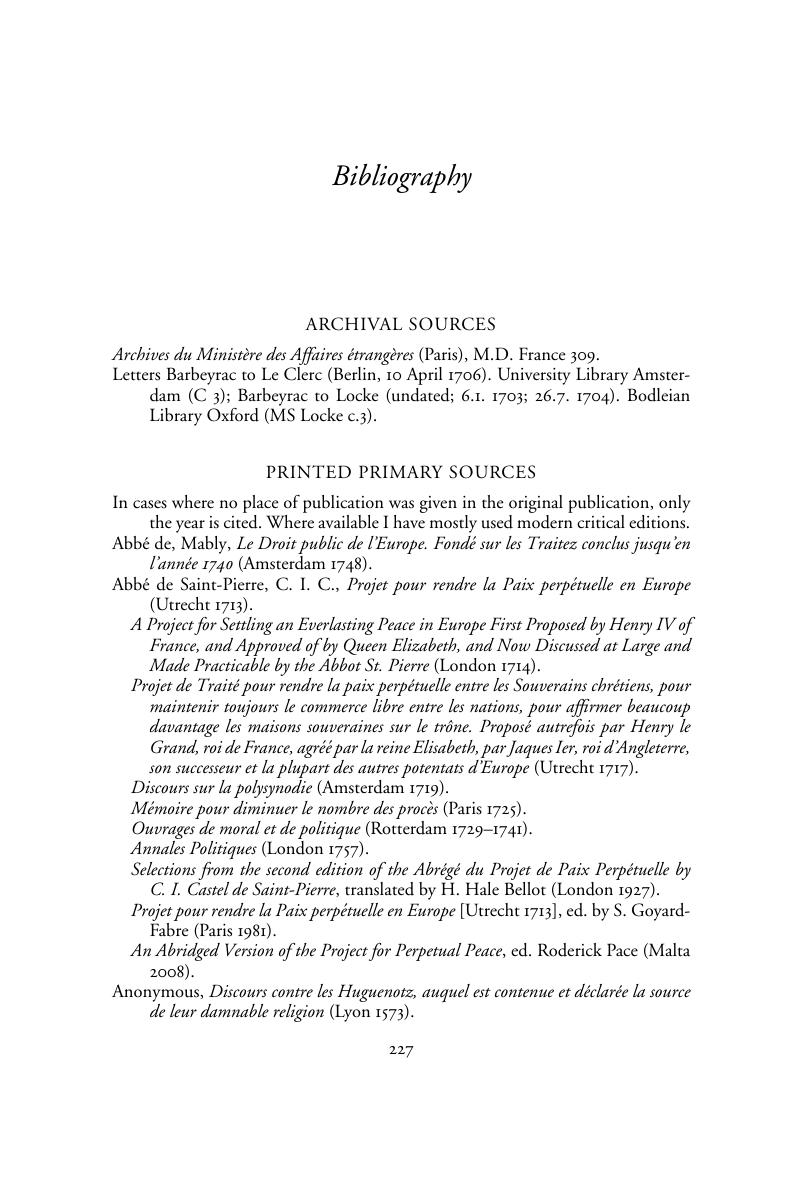

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 March 2017

- Trust in Early Modern International Political Thought, 1598–1713

- Ideas in Context

- Trust in Early Modern International Political Thought, 1598–1713

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Alberico Gentili (1552–1608)

- Chapter 2 Plans For Universal Peace in Europe – The Limits of a Balance of Power

- Chapter 3 Jus Naturae Et Gentium – The Limits of a Juridical Order

- Chapter 4 The Struggle for Hegemony and the Erosion of Trust

- Chapter 5 The Doux Commerce and Interstate Relations

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Ideas in Context

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Trust in Early Modern International Political Thought, 1598–1713 , pp. 227 - 266Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017