Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgmen

- Abbreviation

- WAR AND PEACE

- WORLD WRITER(S)

- ANIMAL AND NATURAL WORLD

- “And the donkey brays”: Donkeys at Work in Virginia Woolf

- Companion Creatures: “Dogmanity” in Three Guineas

- Virginia Woolf's Object-Oriented Ecology

- The Bodies In/Are The Waves

- Stretching our “Antennae”: Converging Worlds of the Seen and the Unseen in “Kew Gardens”

- “The Problem of Space”: Embodied Language and the Body in Nature in To the Lighthouse

- “Whose Woods These Are”: Virginia Woolf and the Primeval Forests of the Mind

- WRITING AND WORLDMAKING

- Notes on Contributors

- Conference Program

- Appendix: Virginia Woolf Conference Exhibit Items, Newberry Library

Virginia Woolf's Object-Oriented Ecology

from ANIMAL AND NATURAL WORLD

- Frontmatter

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgmen

- Abbreviation

- WAR AND PEACE

- WORLD WRITER(S)

- ANIMAL AND NATURAL WORLD

- “And the donkey brays”: Donkeys at Work in Virginia Woolf

- Companion Creatures: “Dogmanity” in Three Guineas

- Virginia Woolf's Object-Oriented Ecology

- The Bodies In/Are The Waves

- Stretching our “Antennae”: Converging Worlds of the Seen and the Unseen in “Kew Gardens”

- “The Problem of Space”: Embodied Language and the Body in Nature in To the Lighthouse

- “Whose Woods These Are”: Virginia Woolf and the Primeval Forests of the Mind

- WRITING AND WORLDMAKING

- Notes on Contributors

- Conference Program

- Appendix: Virginia Woolf Conference Exhibit Items, Newberry Library

Summary

The title of this paper might sound odd, given Virginia Woolf's critique of realism and its privileging of an external object world over the life of the mind. What would the term object-oriented have to do with the writer who claimed that life is “not a series of gig lamps,” but “a luminous halo” (E 4 160)? And how does this relate to ecology? I will begin with Diana Swanson's question in her keynote address during the 2010 conference Virginia Woolf and the Natural World : “can Woolf off er insights and approaches useful to us as we grapple with the ecological crisis of the 21st century” (24)?

Swanson, Justyna Kostkowska and Bonnie Kime Scott are among the scholars who have discussed that question, attending to Woolf's work from an ecocritical and ecofeminist perspective. They all highlight her unsettling of binaries such as subject/object, human/non-human, masculine/feminine, and stress the contemporary relevance of her protest against political and financial systems of exploitation, systems that equate women and nature and dominate both. Ecocritical readings also tend to emphasize Woolf's celebration of connectivity: the capacity of human subjectivity to enter into close communion with non-human life forms. Thus Louise Westling speaks of our embeddedness in “the flesh of the world,” arguing that Woolf's critique of the subject of Western philosophy inspires respect for an “ecosystem in flux” (857). An ecological humanism could be said to unite most ecocritical and ecofeminist readings of Woolf, a stance that foregrounds human responsibility for the natural world.

Responsibility for an Earth community that intertwines human and non-human forms of existence is also central to the object-oriented ontology (hereafter OOO) addressed recently by Graham Harman, Timothy Morton and Mark McGurl, amongst others. However, these thinkers suggest that much ecocriticism “is not thinking coexistence deeply enough” (Morton, “Here Comes Everything” 165). They speak not of an all-embracing human communion with the non-human world, but of a flat, non-hierarchical ontology that is also a form of realism. In Morton's words, OOO demonstrates that “real things exist” and that “there are only objects, one of which is ourselves” (165). In this ontology, human subjectivity has object-like qualities and is confronted with an indiff erent object world, where objects interact in unforeseeable ways that exceed consciousness.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

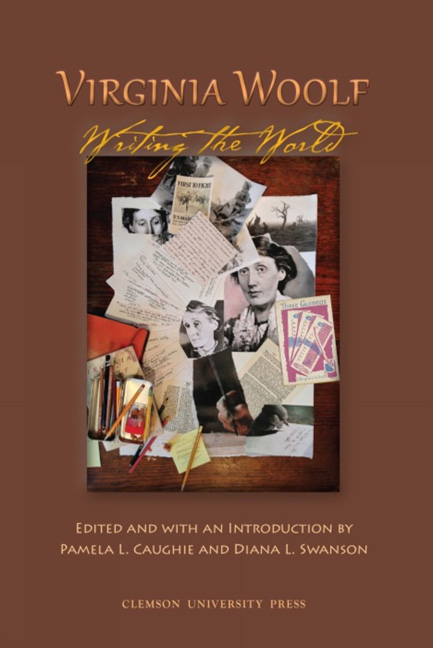

- Virginia Woolf: Writing the World , pp. 148 - 153Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2015