36533 results in Social and population history

The Cambridge Urban History of Europe

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

The Cambridge Urban History of Europe

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

The Cambridge Urban History of Europe

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

Population Control as a Human Right

- International Law and the Global Quest to Curb Overpopulation

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- October 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

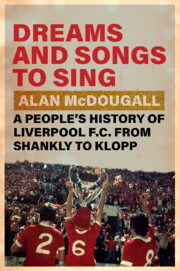

Dreams and Songs to Sing

- A People's History of Liverpool FC from Shankly to Klopp

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- August 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

Imagining Quit India

- War, Politics and the Making of a Mass Movement, Bengal 1940–45

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- July 2025

- Print publication:

- 01 October 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

Citizens to Traitors

- Bengali Internment in Pakistan, 1971–1974

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- June 2025

- Print publication:

- 01 October 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

An Empire of Images

- Visual Culture and the British in India, 1688–1815

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- June 2025

- Print publication:

- 01 October 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

Resilient Communities

- Household, State, and Ecology in Southern Panjab, c.1750–1900

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- June 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

Economics and the Family

- A Social and Political History

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- May 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 May 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

Voices from Calcutta

- Indian Indenture in the Age of Abolition

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- April 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 June 2025

-

- Book

- Export citation

Alexander and the Elephants

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 April 2025, pp. 1-24

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Classifying Occupational Hazards: Narratives of Danger, Precariousness, and Safety in Indian Mines, 1895–1970

-

- Journal:

- International Review of Social History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 April 2025, pp. 1-28

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Why Labor (Partially) Relinquished Its Institutional Resources in Belgium and the Netherlands

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 April 2025, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Distinct Seasonality of Early Modern Casual Labor and the Short Durations of Individual Working Years: Sweden 1500–1800

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- International Review of Social History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 April 2025, pp. 1-30

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Beyond the Great Divergence: Household Income in the Indian Subcontinent, 1500–1870

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- International Review of Social History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 April 2025, pp. 1-25

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction: Wage Systems and Inequalities in Global History

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- International Review of Social History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 March 2025, pp. 1-20

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Ritual and the Enemy Body: A New Approach to Modern Atrocity

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 March 2025, pp. 1-26

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

“The wife is the mother of the husband”: Marriage, Crisis, and (Re)Generation in Botswana’s Pandemic Times

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 March 2025, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Hasidic Dynasties: Geosocial Patterns of Marriage Strategies

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 March 2025, pp. 1-37

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation