1 Introduction

How is academia portrayed in English language children’s literature? From The Water-BabiesFootnote 1 to Tom Sawyer Abroad,Footnote 2 Professor Branestawm,Footnote 3 The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,Footnote 4 and on to Northern LightsFootnote 5 and the Harry Potter series,Footnote 6 professors are established as central characters in children’s books: yet this role has been hitherto unexamined. In this ambitious Element, the representation of fictional academics – individuals teaching or researching within a university or higher education context, or with titles that denote a high rank within the academic sector – is analysed, concentrating on illustrated texts marketed towards children. Focussing on graphic depictions of fictional academics allows the gathering of a corpus which enables a longitudinal analysis: 328 academics were found in 289 different English language children’s illustrated books published between 1850 and 2014, allowing trends to be identified using a mixed-method approach of both qualitative and quantitative analysis of overall bibliographic record, individual text and illustration. This establishes a publishing history of the role of academics in children’s literature, while highlighting and questioning the book culture which promotes the construction and enforcement of stereotypes regarding intellectual expertise in media marketed towards children.

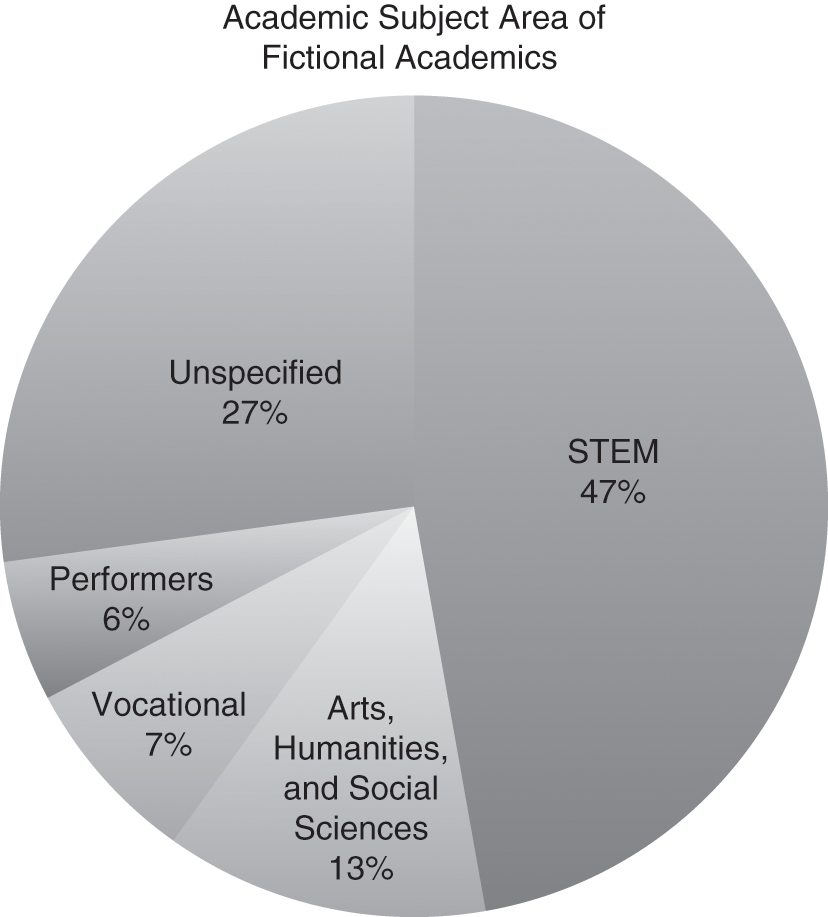

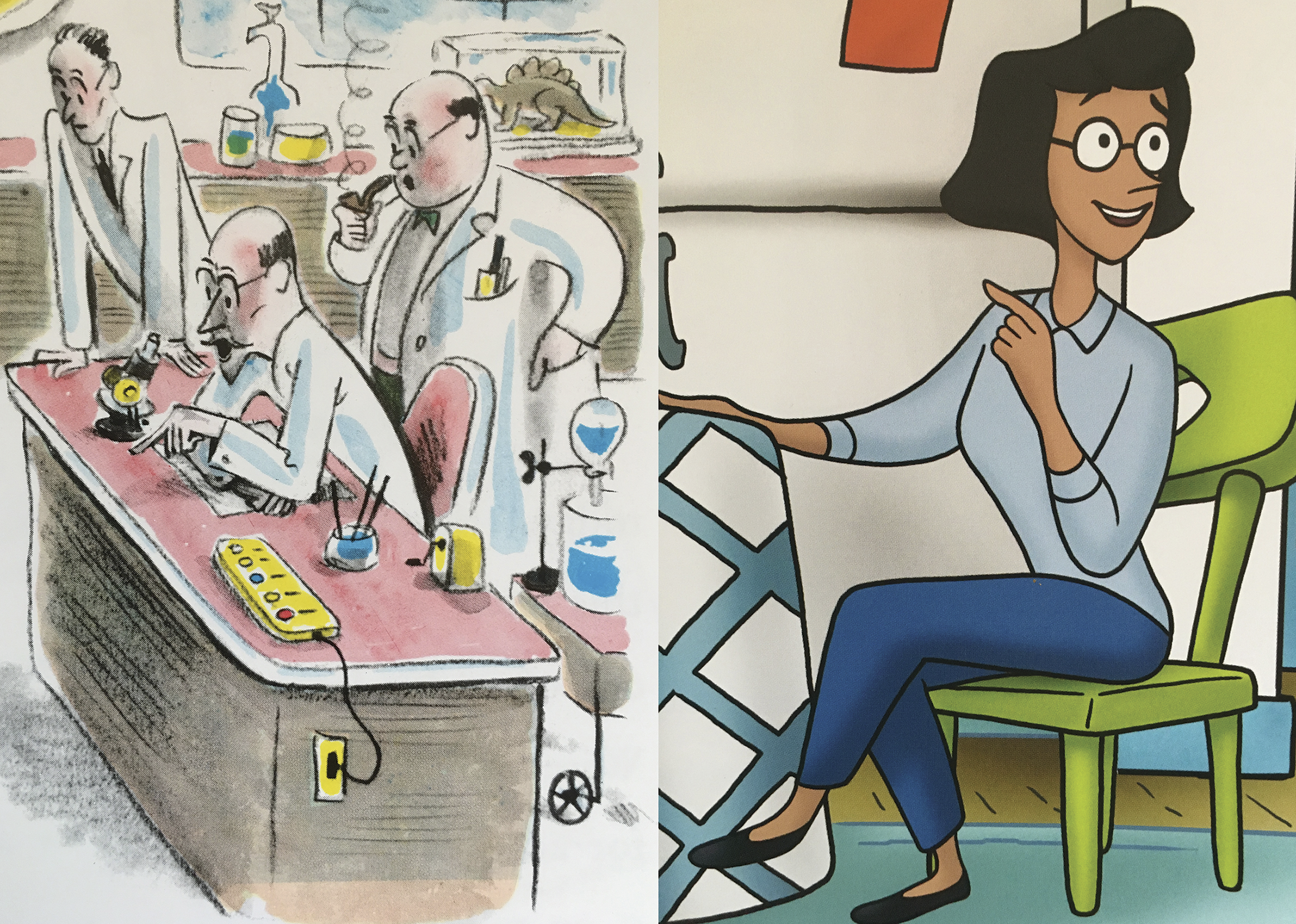

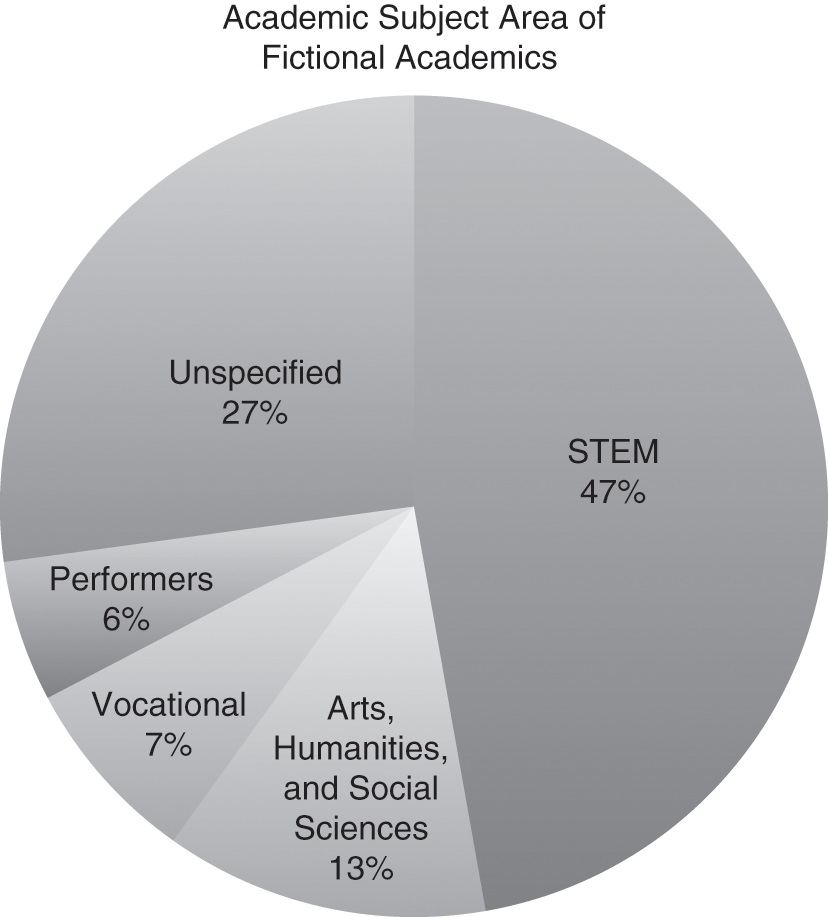

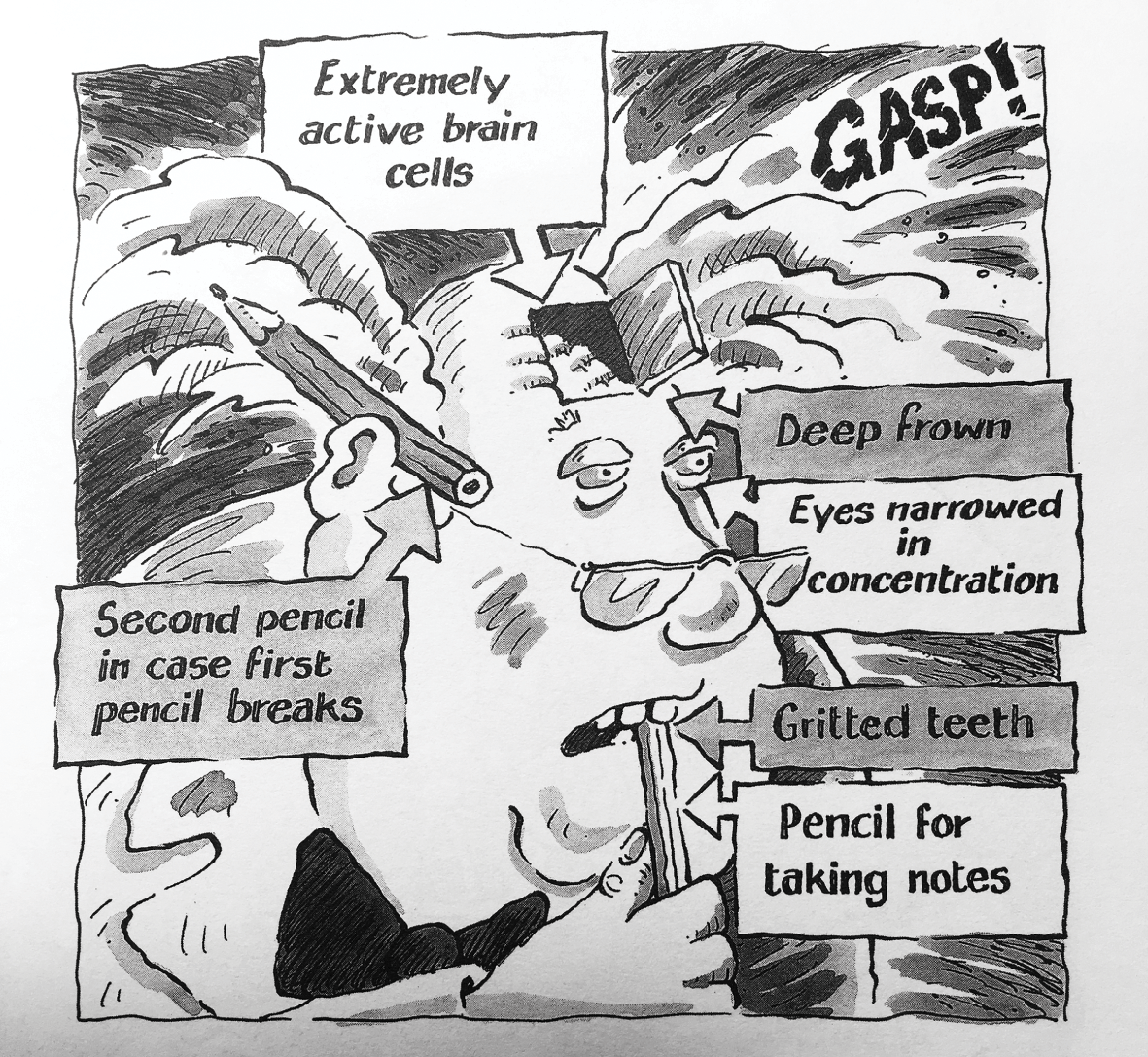

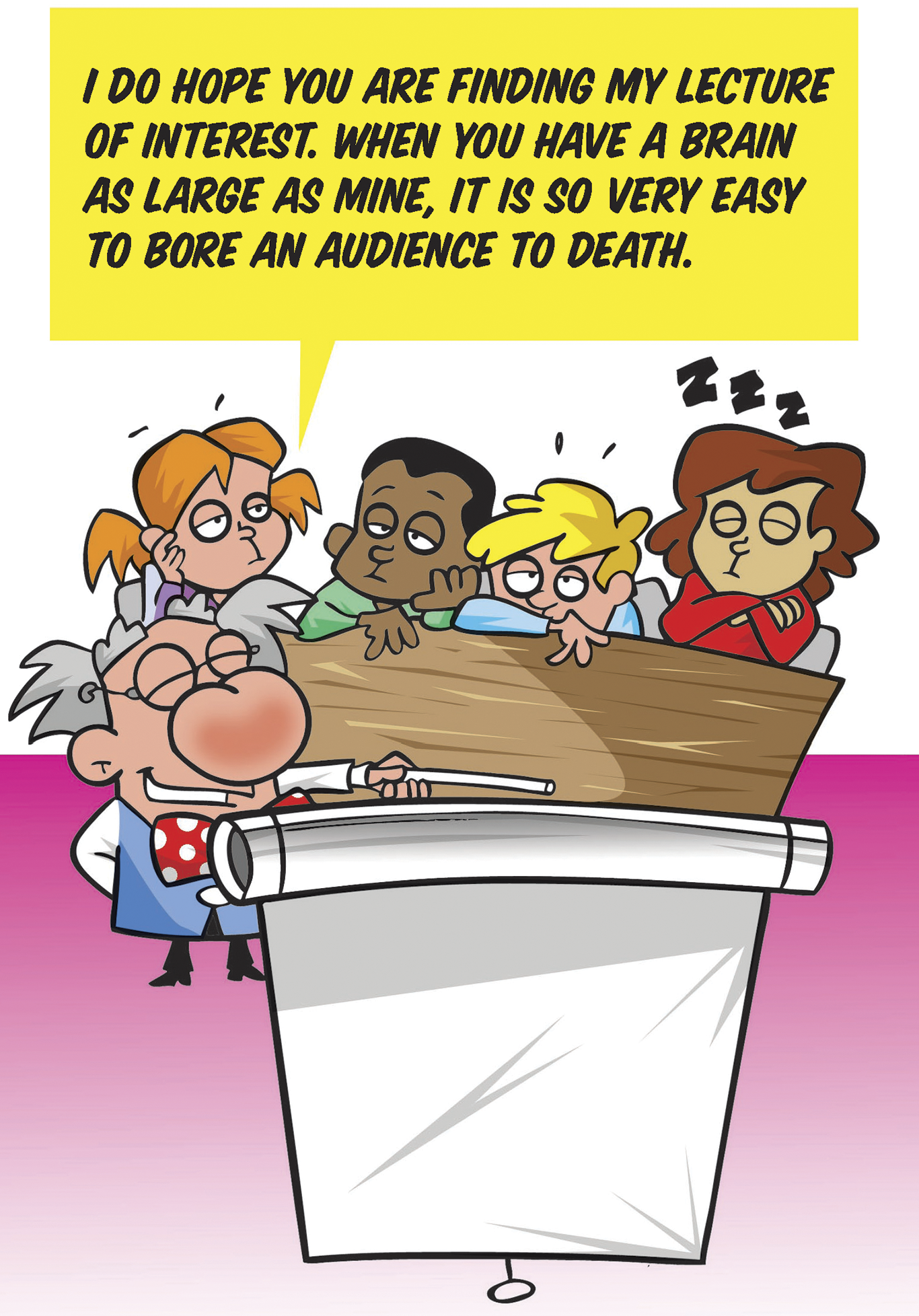

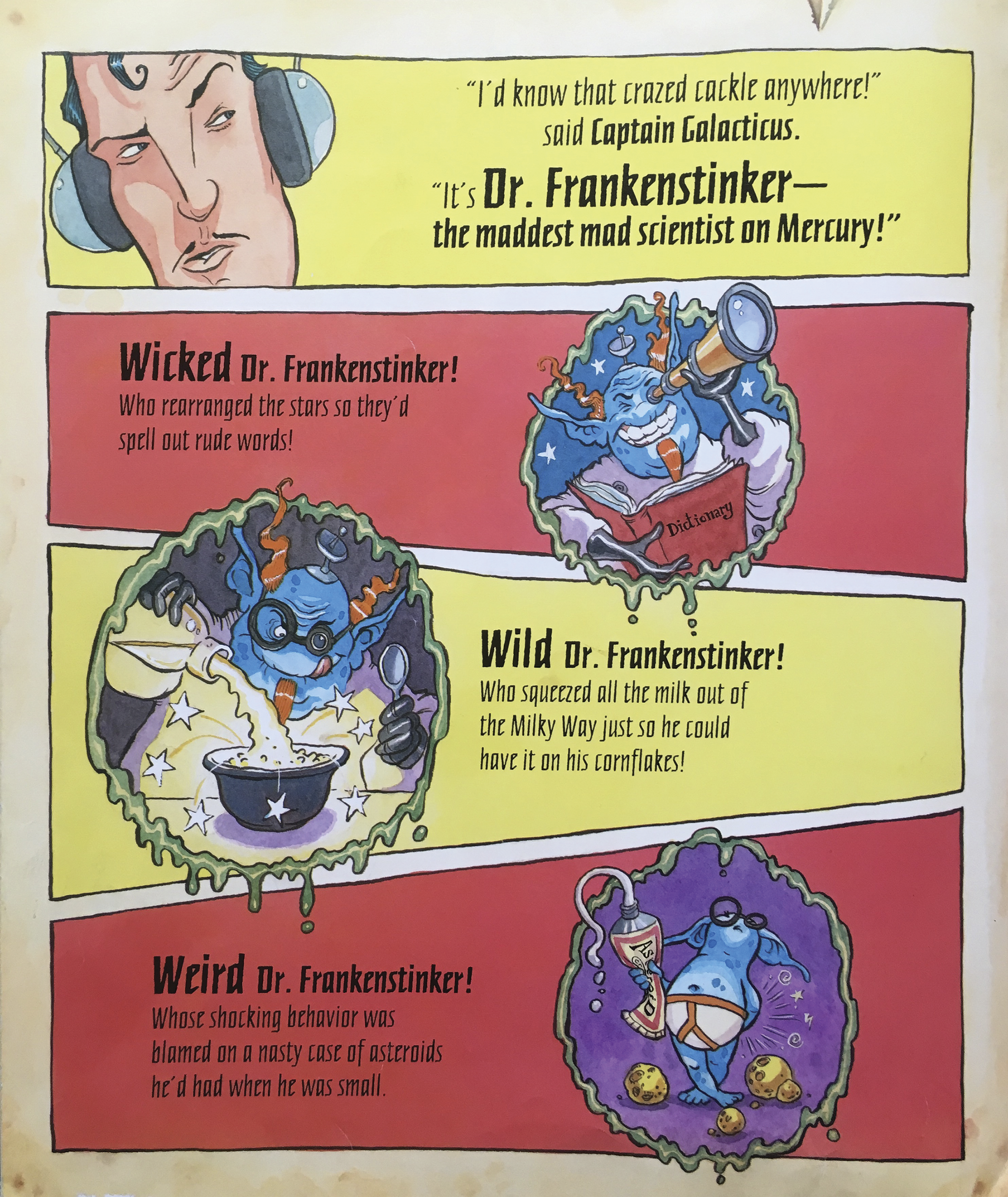

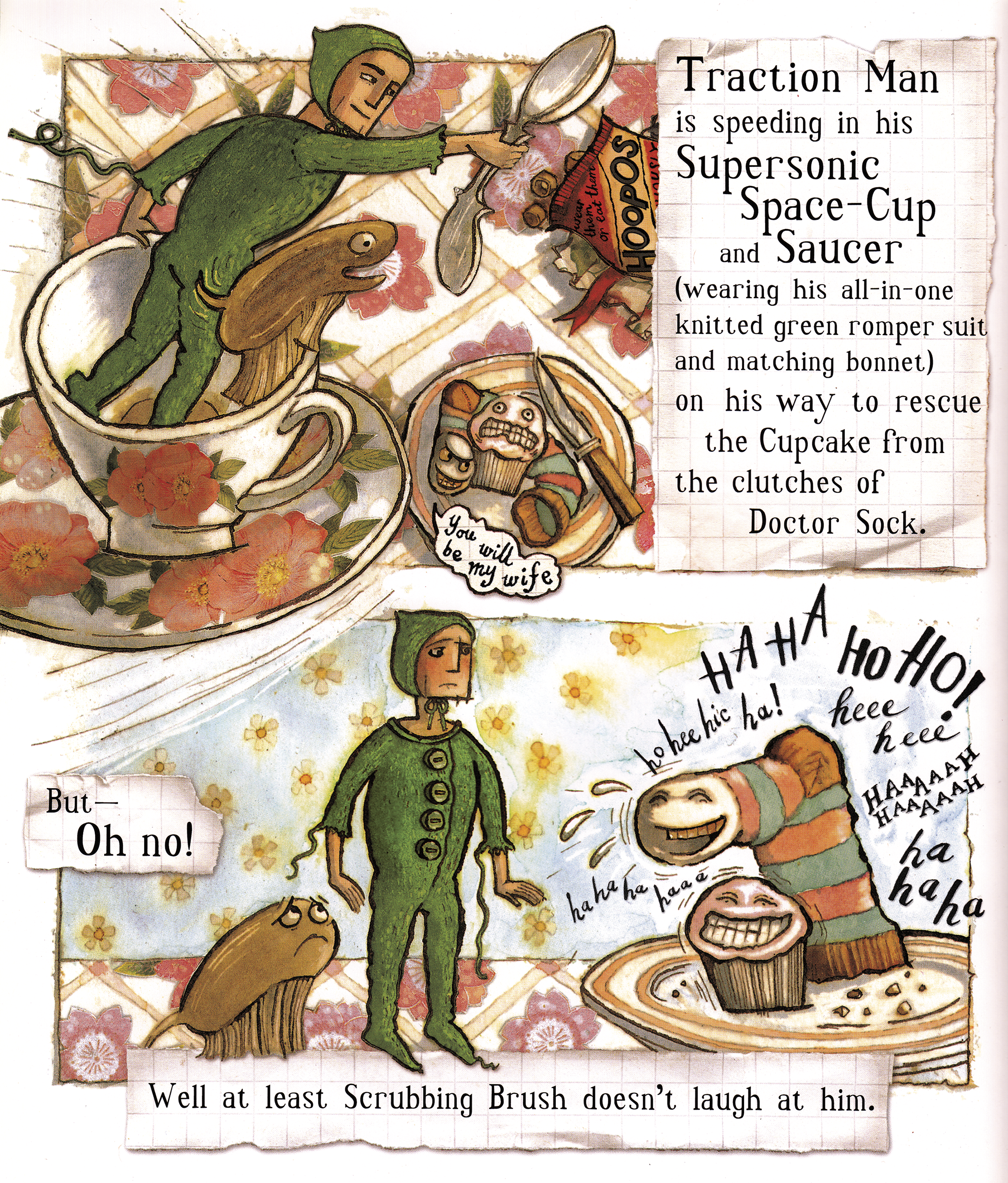

It is academics – teachers and scholars within a higher education setting – rather than other mentions of the university which come to represent the academy in children’s literature: mentions of institutions or their associated structures or customs are rare. The appearance of fictional academics is closely tied to the history of higher education, with the earliest occurrences coinciding with the public funding and growth of the university sector in the latter part of the Victorian period. From then on, fictional academics appear regularly in children’s books, and feature in popular and enduring texts. The incidence of professors in children’s illustrated books increases over the latter half of the twentieth century, although this is closely linked to the fact that there are simply more children’s books being produced within this timeframe. The academics are overwhelmingly white and male and tend to be elderly scientists. Fictional professors can be used as a device to explain and instruct in both fact and fiction. Professors and academic doctors coalesce into three distinct stereotypes: the kindly teacher who is little more than a vehicle to explain scientific facts; the baffled genius who is incapable of functioning in a normative societal manner; and the evil madman who is intent on destruction and mayhem. By the latter part of the twentieth century, the stereotype of the male, mad, muddlehead with absurd hair, called Professor SomethingDumb, is so strong that academics in children’s literature are overwhelmingly presented as such without backstory or explanation. Experts, intellect and higher education are routinely presented as either slapstick or terrifying, in humorous yet pejorative fashion to the child reader, although there is also a trope of the trusted pedagogue or wise old man. These developed stereotypes also establish constraints around which authors and illustrators can easily build characterisation and plotlines and allow publishers to pigeonhole and market texts.

It is first useful to understand how different professions have been studied in children’s literature, focussing on the closest sector that has received some attention: scientists. Next, the method is presented, looking at identifying, accessing and then classifying the texts in a methodological fashion. The corpusFootnote 7 is detailed, giving an overview of the 289 books, and looking at societal and commercial factors underpinning the growth of occurrences of professors in children’s literature over this period of study. Distant readingFootnote 8 of bibliometric data – quantitative computational analysis of descriptions of books in the corpus – is combined with traditional close reading practices: a content analysis of the gathered collection guides attention to areas likely to repay individual focus. The striking heteronormative, patriarchal, white, scientific, maleness of academics in children’s literature is revealed, underscoring previously undertaken research into the lack of diversity in children’s literature, while also showing how stereotypes of academics fossilise and concentrate, becoming increasingly hard to break out from in modern texts. Turning to enduring and popular representations of academics in children’s books, these stereotypes become blueprints for others to follow, or to deliberately fight against.

Representations of academics are tied to wider societal influences, including the depiction of celebrities such as Einstein, popular culture references to book, film and television such as Frankenstein, the resulting public perception of science and scientists, and, more broadly, the ‘cult of ignorance’Footnote 9 in a society which has ‘had enough of experts’.Footnote 10 The corpus demonstrates that, even to a preschool audience, illustrated books are describing advanced learning, intellectual excellence and academic achievement as something to be either feared or laughed at. The ramifications of this for their readership are unknown and unproven. However, the lack of diversity and the mocking nature, showing both the narrow perception of who is allowed intellectual agency in the fictional academy, and what little respect it should be given, potentially impacts the child reader, given previous studies into the effect of negative gender representation in children’s books. It is possible to scope out probable effects of this, and point to how children’s literature can both increase its diversity and step away from damaging stereotypes. In addition, the corpus of texts that have built up over the past century and a half are a lasting testament to the societal undercurrents of patriarchy, uniformity and anti-intellectualism, and how we teach our children to understand these cultural infrastructures. Although this survey concentrates on professors in children’s literature, it is likely that a similar study on different professions would show alarmingly interchangeable results (except vocations in which women have been traditionally ‘allowed’ to excel: teaching, nursing and librarianshipFootnote 11). The corpus has a complex, and sometimes uncomfortable, relationship with its real-life counterpart, simultaneously mirroring, mocking and reinforcing the lack of diversity in the actual academy.

This study pushes the affordances of digital methods, expanding established research methodologies and showing opportunities for others undertaking longitudinal, corpus-based work on changing representations in the study of children’s literature. It is demonstrated that social media tools can be of benefit in the identification of texts to build up large-scale corpora, as well as making use of established methods of library catalogue searching and chaining. Access to digitised texts, particularly those in the public domain and those digitised on demand, improves the range of material that can be included in longitudinal corpora (although copyright restrictions mean a paucity of digitised twentieth-century texts can be obtainable legally). In addition, this research also highlights difficulties in navigating the current state of print-on-demand texts and ebooks, whilst demonstrating opportunities for studying children’s literature at scale, over a long timeframe, using bibliographic data. It is shown that a mixed-method quantitative and qualitative approach can be used to allow both distant and close reading of texts, allowing trends and tropes to be identified, scrutinised and explained, in a ‘genre study’ that ‘oscillates between levels of analysis, training its vision on a constellation of objects then telescoping in for a closer look’ (Rosen, ‘Combining Close and Distant’), this research, then, explores novel methods that may be useful for others in children’s literature studies, and those undertaking longitudinal analyses of popular culture.

Relevant literature, including research into representation in children’s literature and the portrayal of higher education in other media, is surveyed in Section 2. The research approach adopted here, including gathering and analysing the corpus, is presented in Section 3. Section 4 details the results of the analysis, looking at the historical growth of academics in illustrated children’s literature and the main stereotypes that emerge regarding gender, race, class, appearance, subject matter and plot. The main behavioural stereotypes – those of the teacher, the baffled blunderer and the evil madman – are discussed in Section 5, while stereotypes are also presented as a framework for modern children’s authors and illustrators to build upon. The influences on the construction of characters are detailed, including the representation of scientists in popular media, the building of the stereotype via popular and enduring works of children’s literature, the influence on the representation of fictional academics by the constitution (and public perception) of the real-life university sector, and the wider socio-political media climate that fosters anti-intellectualism and populist rhetoric, revealing a complex network of associations referenced by authors and illustrators when depicting academics in children’s literature. Finally, the findings are summarised in Section 6, which questions the dominance of the male, mad, muddlehead, asking what can be done to challenge the stereotype, while discussing limitations of this research, and areas for future study. Many of the early examples discussed in this analysis have also been made available in an open access anthology.Footnote 12

It is hoped that by carrying out this analysis, we can start to ask what we are teaching our children when it comes to experts and intellectual agency. The ridiculous parallel nature of our societal structures – the pale, male and stale universitiesFootnote 13 – and how we reinforce them to our children – the male, mad, muddlehead of children’s literature – are revealed. We can see how children’s literature responds to and, consciously or unconsciously, echoes societal trends in education, politics, history and popular culture. Looking at such a publishing history raises issues of the role of authors, illustrators and publishers in both utilising and standing up to established pejorative stereotypes within the children’s book industry. Need fictional representations – which provide an extension of the world to our children – reinforce negative stereotypes so slavishly? Do these representations encourage us to ask difficult questions about the current constitution of the real-life academy? What can authors, illustrators and publishers do to address these issues? We can see where the shorthand of the male, mad, muddlehead professor emerges from, and then, hopefully, we can – in even a small way – challenge it.

2 Related Research: Representation, Vocation and Higher Education

Although no prior longitudinal analysis of academics and the university in children’s literature has been found, there are various approaches, methods and observations that informed this research. Essentially, this is a study of representation within children’s literature, and there is much prior work done in developing methods in which to identify, classify and analyse specific factors in children’s books: these are briefly surveyed. Such analyses are important given the effects that dominant narratives can have on child development: an overview is given of material that investigates this link, indicating why this type of study matters. Previously published research on professions in children’s literature is summarised, followed by work undertaken which analyses scientists both in books written for a childhood audience and the wider media landscape, including work on how academia is presented in media targeted towards older audiences (including comic books, and popular culture). Although there is no published work on academics in children’s literature, there is a wealth of methods that can be adopted and adapted from these prior studies.

2.1 The Study of Representation in Children’s Literature

Before considering the portrayal of academics in children’s books, it is useful to survey the long history of the study of representation in children’s literature. Representation studies – focussing on the analysis of particular aspects featured in children’s literature by: their illustration; the tone and word choice used in textual description; and how these two interact – are usually targeted towards broad measures such as gender,Footnote 14 ethnic diversity and cultural identity,Footnote 15 parental roles,Footnote 16 sexualityFootnote 17 and disability.Footnote 18 Qualitative and quantitative analyses reveal time and time again that children’s literature is severely lacking in all areas of diversity.Footnote 19 Representational analysis is also used to study subjects in children’s literature as diverse as behavioural issues,Footnote 20 school environments,Footnote 21 bereavement,Footnote 22 Art MuseumsFootnote 23 and the appearance of objects such as the moon.Footnote 24

These previous studies, which often analyse written and visual text in both qualitative and quantitative approaches, informed the methodology. The number of books analysed varies, depending also on the methods used: from close reading – with two books,Footnote 25 four,Footnote 26 thirteen,Footnote 27 fourteenFootnote 28– to the use of qualitative methods – with twenty-two books,Footnote 29 twenty-five books,Footnote 30 thirty-three,Footnote 31 thirty-seven,Footnote 32 seventy-three,Footnote 33 seventy-four,Footnote 34 seventy-eight,Footnote 35 eighty,Footnote 36 eighty-four,Footnote 37 ninety-one,Footnote 38 100,Footnote 39 111,Footnote 40 200,Footnote 41 300,Footnote 42 455,Footnote 43 537Footnote 44 and 952.Footnote 45 Given the relatively large size of our corpus, a mixed method approach was both helpful and required, looking to the studies that carried out an analysis of over seventy books, using a content analysis methodology detailed in Section 3.

2.2 Why Study Representation in Children’s Literature?

Why does it matter to study such representation and to identify stereotypes? Entertainment media affects the behaviour, ethical approach, perspective, outlook and conduct of consumers.Footnote 46 Much research into diversity in children’s literature assumes stereotypes are bad without explaining their mechanisms or the evidence that exists for their negative affect on child development. To counter this, Peterson and LachFootnote 47 surveyed previously publicised research into the effects of gender stereotyping in children’s books on child development, showing ‘that the reading materials to which we expose children shape their attitudes, their understanding and their behaviour’,Footnote 48 indicating that stereotypes

may impair the development of positive self-concepts, and induce negative attitudes towards the child’s own developmental potential and toward that of other children. They may significantly alter the child’s cognitive development, presenting them with an inaccurate and potentially destructive world-view … Educators would seem to bear a special responsibility in facilitating further change.Footnote 49

Likewise, SteyerFootnote 50 updates this survey of research into the effects of gender stereotyping on children, including television, film, books, video games and the Internet, showing that negative portrayals had ‘a negative effect on female self-efficacy’.Footnote 51 Research into the effects of other stereotypes is in its infancy but is expected to closely follow these findings associated with gender stereotypes, and, indeed, the very threat of being judged negatively due to stereotypes affects performance.Footnote 52 Negative stereotypes can be subverted; for example, ‘exposure to non-sexist gender portrayals may be associated with a decrease in stereotypical beliefs about gender roles’.Footnote 53 The success of ‘media literacy education to reduce the media’s role in perpetuating stereotypes – training people in the skills to “interpret, analyse, and critique” negative stereotypes ’ – is not yet well evidenced,Footnote 54 but it offers a potential source of intervention into the perpetration of bias.Footnote 55 Understanding the source, mechanism and prevalence of representational stereotypes helps unpack their power and provides a means by which to critique and suggest alternatives. The study presented here aims to provide an analysis of how academia is portrayed in children’s literature, in the hope we can both understand, improve and learn from it.

2.3 Analysis of Vocations in Children’s Literature

Analysing diversity in children’s literature, or the lack thereof, is a major contemporary topic for the research community.Footnote 56 Previous work analysing the representation of different professions in children’s books focuses on occupational gender stereotypesFootnote 57 and how they have changed over time: Allen et al.Footnote 58 found a weak trend towards more egalitarian representation, although males are more likely to be characterized as ‘active, outdoors, and non-traditional … in diverse occupations more often than females’.Footnote 59 Tangentially, a strand of research also follows, considering how occupational stereotypes are perceived by, and affect, children.Footnote 60 The representation of individual, specific vocations in children’s picture books has received relatively limited attention, the focus instead having been primarily on distinct professions identifiable to children, such as doctors,Footnote 61 veterinarians,Footnote 62 librarians,Footnote 63 farmers,Footnote 64 soldiersFootnote 65 and teachers.Footnote 66 These studies examined various areas such as gender, ethnic diversity (the lack of diversity in both gender and race is a common cause for concern) and characteristics of the individuals portrayed, to look at both the explicit and implicit messages about these professions that the illustrations and text were conveying.

Of greatest interest is previous work done on the representation of scientists in children’s literature (in both fiction and nonfiction): it should be borne in mind that scientists are not all academics, and academics are not all scientists, but there is some understandable overlap between the two, and previous studies proved useful to this approach. Rawson and McCool examined images of 1657 scientists in 111 nonfiction juvenile trade books, demonstrating that ‘Scientists in these books are shown in a wide variety of settings and are largely missing stereotypical features’; however, ‘the standard image of the scientist as a White male is still perpetuated in these titles, and this is a cause for concern’. Footnote 67 Van Gorp et al. looked at the representation of scientists in a range of books and comics aimed at Dutch children and teenagers, identifying seven main stereotypes: ‘the genius, the nerd, the puzzler, the adventurer, the mad scientist, the wizard, and the misunderstood genius’,Footnote 68 stressing that scientists in children’s fiction were generally more stereotypically eccentric, undertaking more risky, useless experiments than those in factual texts. Similar findings emerged from Van Gorp and Rommes’ study of scientists in Belgian comic books.Footnote 69 There has been a great deal of work done on the representation of scientists in media marketed towards adults, including literatureFootnote 70 and film and television,Footnote 71 which will contribute to the discussion of the research findings: scientists in fiction are generally old, white malesFootnote 72 with a master narrative of the scientist as a bad and dangerous person linked to societal fears regarding the impact of technological change, which is particularly pronounced after the Second World War.Footnote 73

2.4 Analysis of Higher Education in Popular Culture

Previous analysis of depictions of higher education in popular culture suggests

the dominance of straight white men, the lack of diversity, privileging certain types of institutions, and non-academic depictions contribute to anti-intellectual representations of higher education.Footnote 74

Even the campus novel itself, analysed in Showalter, while usually ‘sensational and apocalyptic’,Footnote 75 adheres to these well-established hierarchies, dealing with anything that deviates from them in regard to sexuality or race in ways which are ‘quirky, pedantic, vengeful, legalistic, and inhumane. The ivory towers have become fragile fortresses with glassy walls’.Footnote 76 There are well-established tropes of who gets to have intellectual agency within the fictional academy in books, television, and film, with gendered portrayals that ‘unjustly and inaccurately privilege men within the context of a higher education environment’.Footnote 77

The analysis of higher education in specific comic strips has been carried out, such as in Tank McNamaraFootnote 78 and Piled Higher and Deeper.Footnote 79 A qualitative analysis of the representation of academia in American comic books published between 1938 and 2015 found examples of higher education, including settings and characters, in over 700 comic books, and purposively sampled them to analyse how Higher Education is depicted in generalFootnote 80 and how professors are depicted specifically.Footnote 81 Expertise is the defining characteristic of comic book academics:

Professors are established as the characters that innovate, discover, examine and create both cutting edge technology and bold scientific experiments that are often needed to save the day.Footnote 82

The dominance of STEM subjects is also identified, and the absence, or grotesque portrayal of women, leading to

possible percussions for the validity of an inclusive profession and non-differentiated expectations of students, or others, based on gender, race, and discipline.Footnote 83

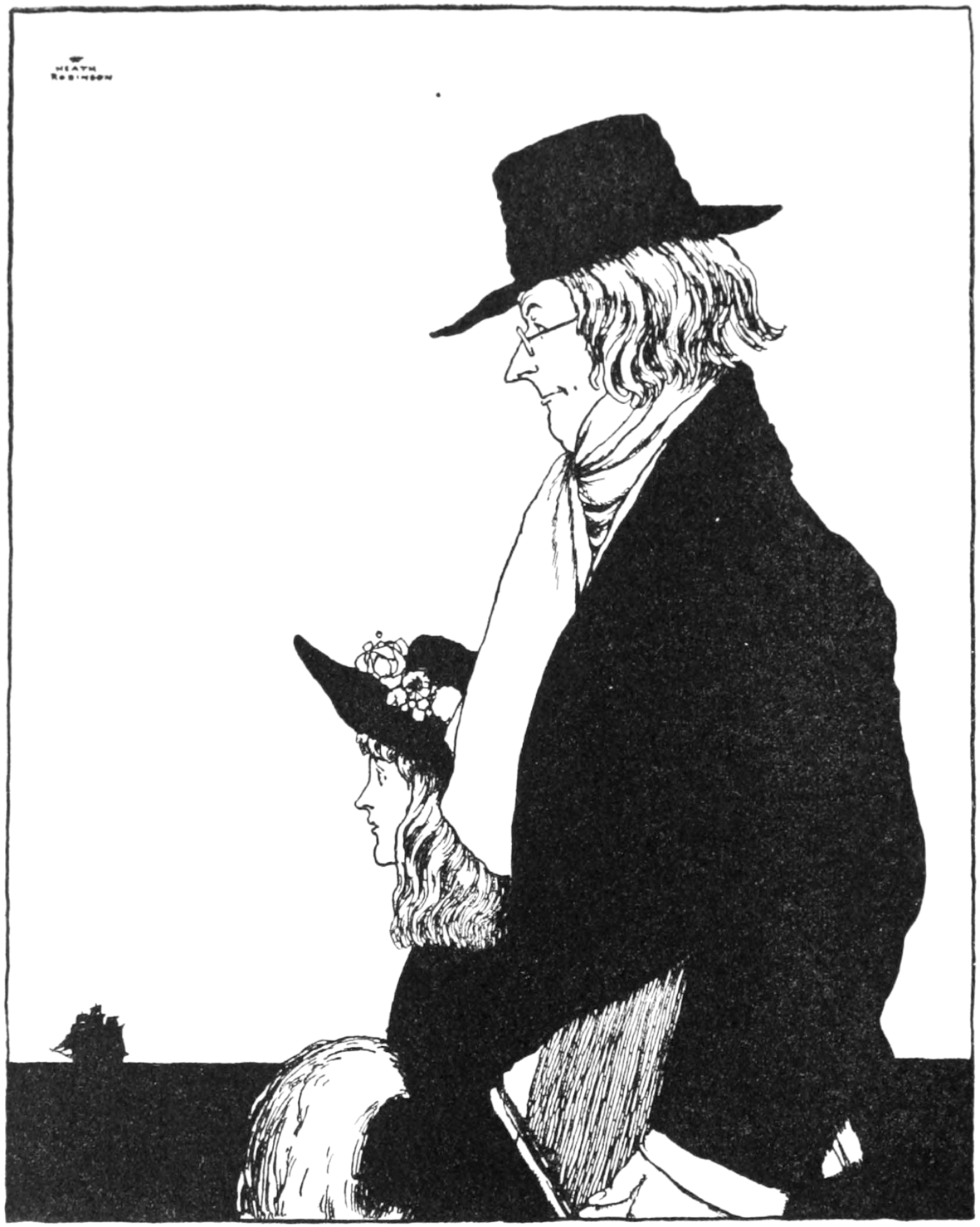

Interestingly, ‘only rarely do professors deliberately work for nefarious purposes’,Footnote 84 puncturing any expectations of evil scientists. ReynoldsFootnote 85 traces the history of academia in comic books, finding both static and dynamic elements of depiction of fictional higher education. College itself is ‘a spaciously green, safe space that doesn’t really change … connect[ing] with and bolster[ing] public imaginings of US institutions of higher education’ but ‘depicting fictional institutions of indistinguishable type’.Footnote 86 The act of going to college provides a structural narrative convention around which much action pivots. Students are a dominant focus, but there are also many professors ‘who are overwhelmingly male’ that ‘feature in narratives as main or supporting characters’ acting ‘as villains or rivals in some comic book narratives’.Footnote 87 Women tend to have peripheral roles. Heroes are all white ‘but perhaps unsurprisingly, villains might not be’,Footnote 88 and there is limited inclusion of diverse characteristics. Reynolds suggests that the ‘blanket anti-intellectual discourse in media related to higher education’ is replaced with ‘more sophisticated understandings of these themes’,Footnote 89 sometimes challenging, but sometimes reinforcing, anti-intellectual messages. These studies provide a useful counterpoint to the work presented here; however, many of the comics surveyed are produced for a much older age range than is focused upon in this analysis.

2.5 Analysis of Individual Children’s Texts

There are a few analyses of individual academic scientists in children’s fiction. For example, Smith’s examination of the ‘kindly’ Professor Ptthmllnsprts (‘Put them all in Spirits’) from The Water-BabiesFootnote 90 in his overview of the importance of science to the Victorian novel highlights how

Even the well-meaning naturalist could become consumed by his interests to the detriment of his connections with, and responsibilities towards, family, friends and community.Footnote 91

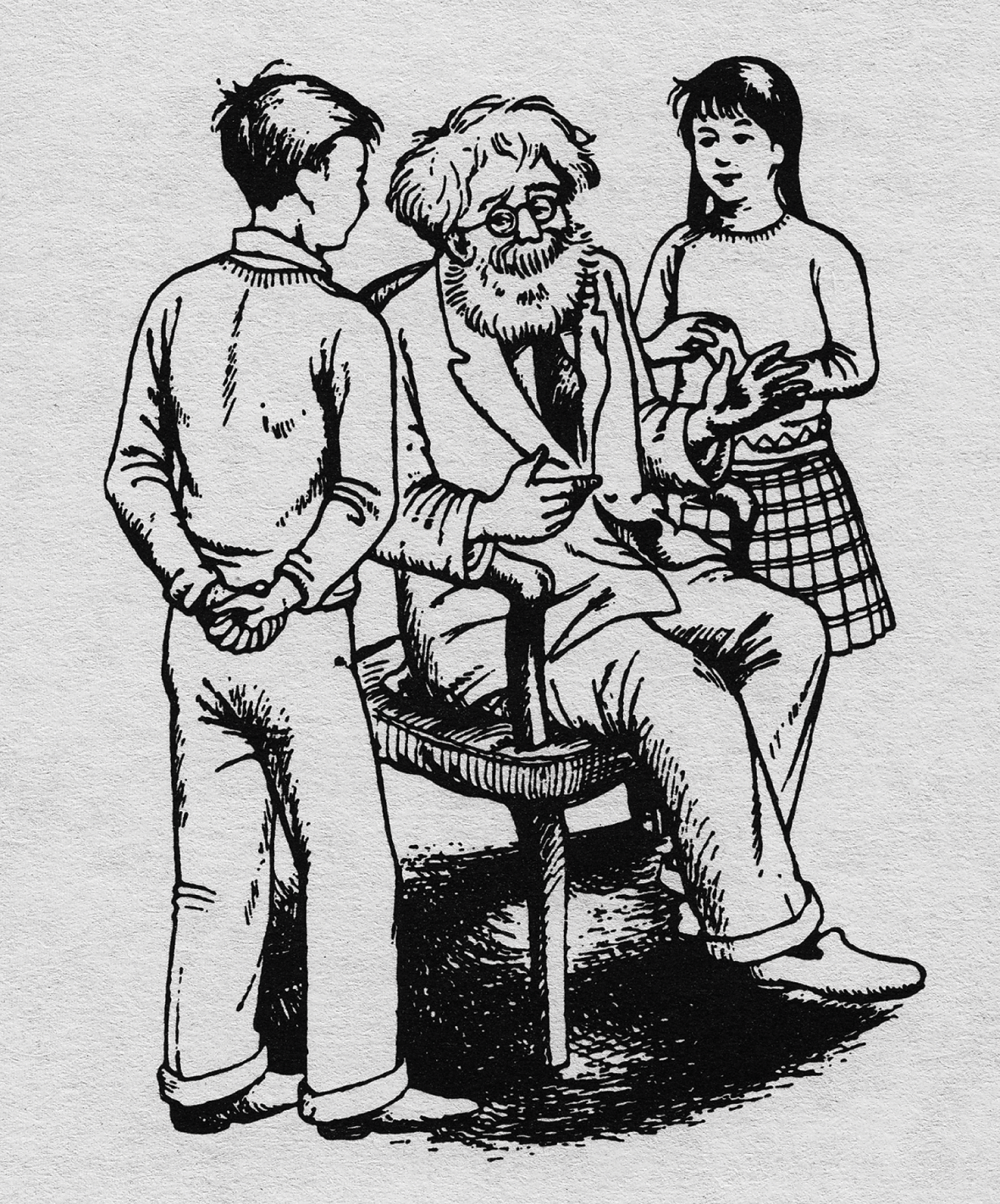

Ptthmllnsprts is considered ‘a symbol of secular science … particularly illustrated by his obsession with collecting’ in Talairach-Vielmas.Footnote 92 Giddens uses Ptthmllnsprts as a frame to discuss the illustration of science to a nineteenth-century childhood audience, showing how the adult body dominates depictions of science.Footnote 93 Bell’s consideration of Professor BranestawmFootnote 94 looks at the ‘ways in which images of children or the childlike are used in the construction of the scientist’.Footnote 95 JafariFootnote 96 explores the Jungian archetype of the wise old man in The Chronicles of Narnia,Footnote 97 examining Professor Digory Kirke’s role in temporally and intellectually framing the series from The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe onwards.Footnote 98 Much academic interest surrounds the Harry Potter series;Footnote 99 for example, see Heilman,Footnote 100 WhitedFootnote 101 and Fenske,Footnote 102 with publications mentioning the professorial teachers at Hogwarts such as Birch, who demonstrates that Albus Dumbledore is a paragon: ‘kind and gentle, energetic and wise, trusting and trusted, experienced and patient’Footnote 103 and that Minerva McGonagall’s ‘appearance, her personality, and her pedagogy conjure images of a stereotypical school-marm’.Footnote 104 However, Birch stresses the ‘absence of intellectual work by teachers as well as the singular and completely school based identities’,Footnote 105 and there is little consideration of the academic achievements or standing of the professors found in the Harry Potter critical literature (or, indeed, in the texts). Overall, considerations of lone academics are rare. There has been no prior overarching work found on trends and tropes in the representation of academics, more broadly framed, in children’s literature.

2.6 Conclusion

The literature review has shown that there has been no prior overarching research on the representation of higher education in children’s books, despite both the importance of these institutions to today’s society, and the fact that academics (such as professors and non-medical or research doctors) feature in many popular and enduring works. Nowadays, university is an expected educational ‘next step’ for a large proportion of school-leavers in the Western world, and the lack of prior work on how academia is portrayed to a childhood audience through literature is therefore surprising. There are useful research methods that can be appropriated from the analysis of representation in children’s literature and other media, and relevant prior work on how specific professions, including scientists, are portrayed and perceived in children’s literature. Understanding the representation of the university sector in books marketed towards a young audience is important, given the effect stereotypes and portrayals have on children’s actuation and development, and this analysis will reveal what messages are being portrayed to young children about intellectual achievement and higher education.

3 Research Methodology

What methods could be used to study how academics are depicted in children’s literature? A search of English language children’s books indicated that the people, rather than the places, are the focus of both fiction and non-fiction texts, and a methodology was developed to analyse illustrated fictional academics. This gathered core information on features of academics, using both textual references and analysis of illustrations. It is acknowledged that there are many more professors, doctors and researchers which appear in the text of books marketed towards children that do not have illustrations: the requirement for illustration also somewhat limits the corpus to a manageable size to facilitate a longitudinal study, while firmly focussing on texts produced for a young childhood audience. Illustrations also impart further information about the representation of academics than analysing textual descriptions alone, providing a rich corpus from which to draw upon.

There are two aspects to the method necessary for a study of this nature: first, the collection of the unique corpus, and second, the framework used to analyse it. Given the scope of this research, and the variety of texts identified for inclusion, clear decisions had to be made to guide both.

3.1 Building the Corpus

The corpus was constructed over a four-year period between April 2012 and April 2016, gathering all relevant texts possible that were published before the close of 2014. The gap between the end of the census and analysis allows for the fact that books often take a while to appear in library catalogues or other online environments. The use of digital resources was central to this task, facilitating the commonly used information seeking behaviour of starting, chaining, browsing, differentiating, monitoring and extractingFootnote 106 to identify relevant examples. Seed keywords included many terms related to academia (and their plurals): academic; academy; campus; college; degree; doctor; faculty; fraternity; fresher; freshman; graduate; graduation; lecturer; polytechnic; professor;Footnote 107 research; researcher; semester; sophomore; student; term; tutor; undergraduate; university; and varsity.Footnote 108 The irony is not lost here that searching for illustrated academics in children’s books required textual searches: there is no current way to allow searching for aspects of academia that may be pictured, such as mortar boards or academic gowns and hoods, in illustrated texts, many of which are still in copyright and few of which are available in digital form. Such representations, without textual explanation, may also only be of old-fashioned schoolteachers (for example, this is surely the case with the bespectacled, gowned scholars seen in the background of the town square in Zeralda’s OgreFootnote 109).

Standard online bibliographies, major library catalogues, specific children’s literature resources and digital libraries were consulted. These included WorldCatFootnote 110 and libraries such as The British Library,Footnote 111 The National Library of Scotland,Footnote 112 The National Library of AustraliaFootnote 113 and The Library of Congress.Footnote 114 Specific catalogues of children’s literature that were utilised include The International Children’s Digital Library,Footnote 115 The International Youth Library,Footnote 116 The Children’s Literature Collection at Roehampton University,Footnote 117 Children’s Literature Research Collections at the University of Minnesota,Footnote 118 The National Centre for Children’s Books (UK),Footnote 119 The Center for Children’s Books at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,Footnote 120 The Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature at the University of FloridaFootnote 121 and the Children’s Literature Collection at the State Library of Victoria.Footnote 122 Digital libraries used included Google Books,Footnote 123 Hathi Trust Digital Library,Footnote 124 the Internet ArchiveFootnote 125 and the Digital Public Library of America.Footnote 126 The coverage and cataloguing in these resources varied, but the combination of a positive match on at least one of the search terms and a note that a book was illustrated was enough to check a copy, ideally of the physical book or a digitised version from a reputable source, for an instance to be included in this corpus. In some cases, user-generated videos of children’s books being read aloud, which had been posted to YouTube,Footnote 127 also proved to be a useful resource for the checking of details (although the problematic relationship of these amateur videos to official publishing channels is acknowledged).

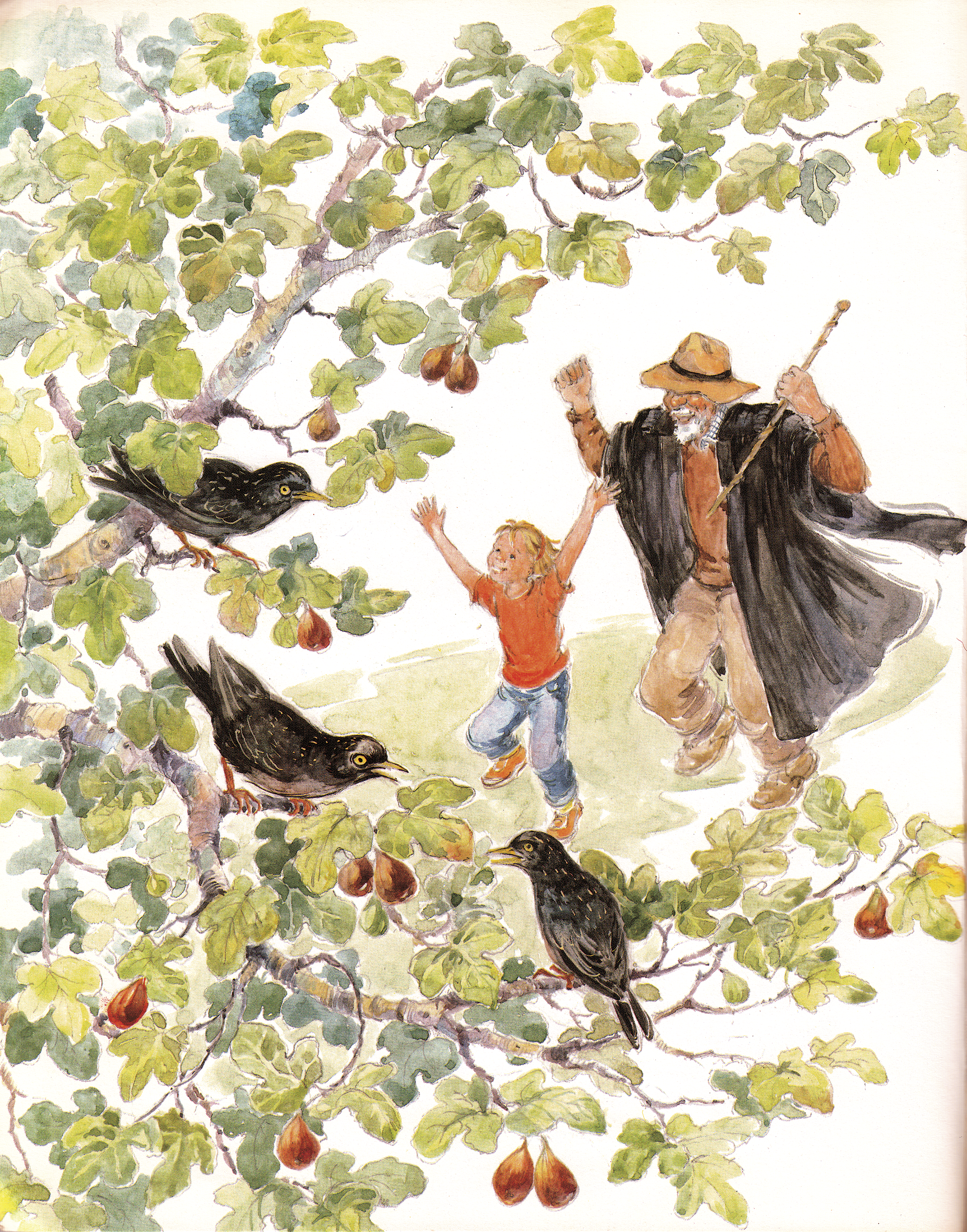

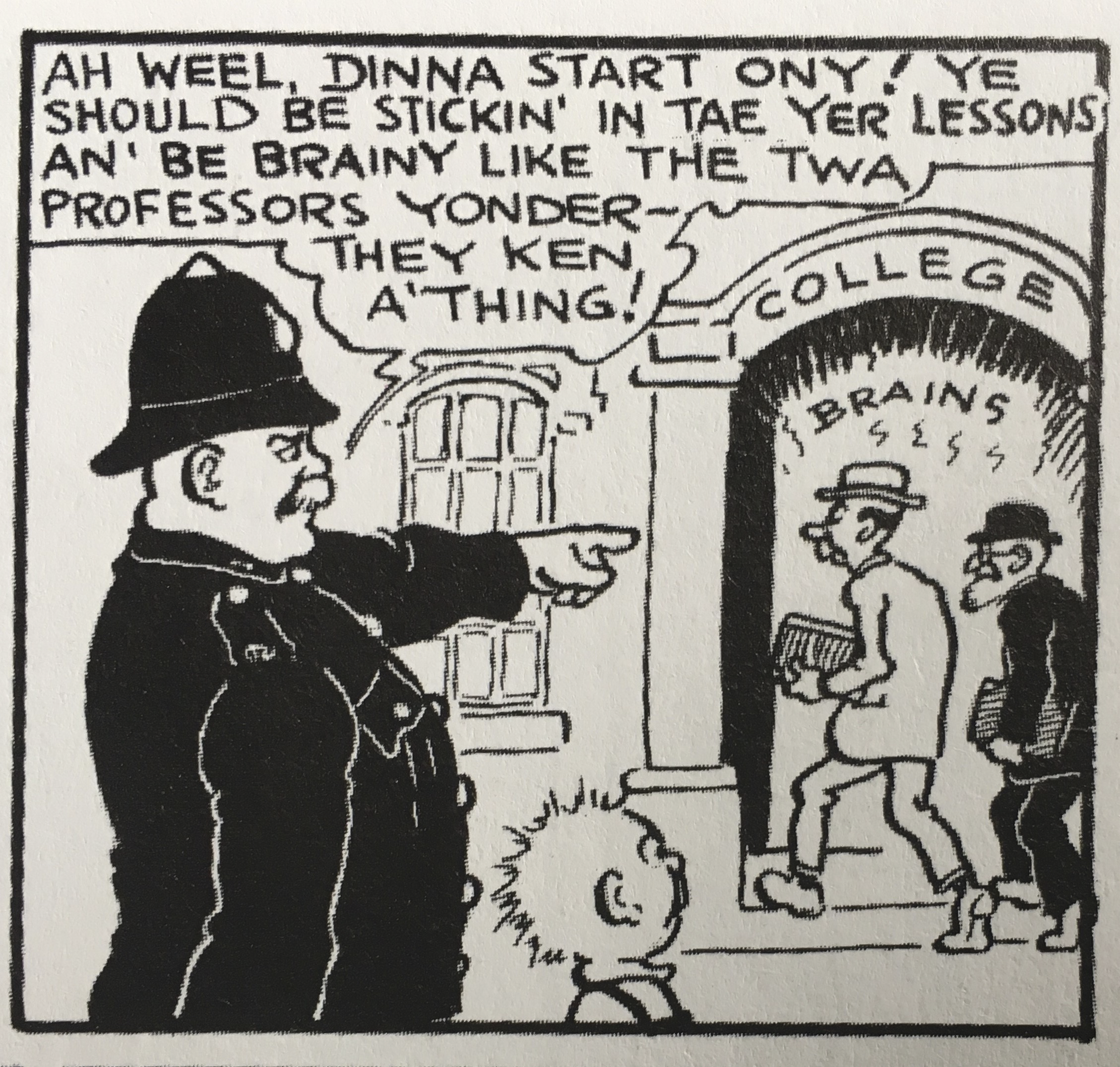

In addition to traditional bibliographic methods, the building of the corpus was facilitated by interacting with online communities and via social media. Many of the mentions of universities, professors or doctors do not appear either in the title of the book or in library catalogue descriptions, meaning examples were not apparent through a traditional literature search: for example, Professor Euclid Bullfinch in Danny Dunn and the Antigravity PaintFootnote 128 or Mrs Hatchett, Doctor of Literature in The Pirate’s Mixed-Up Voyage.Footnote 129 However, there are various other online sources that contain textual details, including listings on Amazon,Footnote 130 eBayFootnote 131 and online marketplaces specialising in rare books such Abe Books,Footnote 132 AlibrisFootnote 133 and Biblio:Footnote 134 these are useful precisely because they contain alternative descriptions to library catalogues. In particular, user reviews on Amazon and other social media sites for reviewing, tracking and rating books, such as GoodReads,Footnote 135 LibraryThing,Footnote 136 BookDigitsFootnote 137 and Shelfari,Footnote 138 and fan forums such as posts on Stack Exchange,Footnote 139 revealed university-related content. The author’s own use of social media throughout this project helped identify candidates: finds were parked on a dedicated Tumblr microblog, ‘Academics in Children’s Picture Books’,Footnote 140 and the topic was regularly discussed on the social media platform Twitter.Footnote 141 In 2014 a preliminary analysis of the corpus was presented on the author’s blog,Footnote 142 which was syndicated and featured elsewhere onlineFootnote 143 and in print in the Times Higher Education.Footnote 144 This activity encouraged others to get in contact to propose further candidates for inclusion: 20 per cent of the corpus was provided by readers’ suggestions, which would not have been found by any other method. For example, two professors in an Oor Wullie cartoon,Footnote 145 spotted by Ann Gow and sent to the author via Twitter: ‘Crivens, profs from Oor Wullie, 1944. A’bodys stereotype.’Footnote 146

It is acknowledged that there will be other relevant texts that have not been found,Footnote 147 but the limits of both traditional and non-traditional bibliographic methods to gather candidates for the corpus have been exhausted.Footnote 148 In addition, the online information environment is ever shifting and it is difficult to replicate the conditions and sources upon which a search was based: if this corpus were started in the ‘now’ of the reader, it would likely be different to the one on which this analysis is based, which was gathered between 2012 and 2016. The constraints of copyright upon digital libraries plays a part in the ease of finding texts, with many pre-1920s texts being available digitally in the public domain, and those after unable to be computationally full-text searched.

Paradoxically, given how useful online search mechanisms were to finding texts, it was incredibly difficult to identify bona fide candidates for the corpus printed after 2007, given the exponential rise in self-published ebooks. Although the ‘[s]elf-publishing of books has a long and illustrious history’,Footnote 149 the ease at bringing self-published books to market changed in 2007 when the Kindle Digital Text Platform was launched, allowing authors to format and upload texts for sale as self-published books on Amazon.Footnote 150 ‘Publishers’ such as CreateSpace, iUniverse, Lulu Enterprises, Inc., Xlibris Corporation and AuthorHouse are actually print-on-demand services which individually print ebooks once a sale has been made, supporting the self-publishing market.Footnote 151 At the time of writing, there are over one million self-published books listed on Amazon via its CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform service.Footnote 152

These changes in the publishing environment have resulted in the flooding of the literature market with digital-only texts of variable quality, with little signs of readership.Footnote 153 For example, an imprint of Speedy Books LLCFootnote 154 giving itself the author name ‘Baby Professor’ uploaded 102 digital-only children’s books for Kindle to Amazon on 15 December 2015 alone.Footnote 155 Given the huge number of ebooks of questionable quality identified by the methodology that were published after 2007, it was decided to exclude digital-only, or print-on-demand, texts from the corpus. Examples thus excluded on these grounds include the print-on-demand Professor Woodpecker’s Banana SandwichesFootnote 156 and the only-available-in-ebook The Adventures of Professor Bumble and the Bumble Bees: the pool,Footnote 157 neither of which have been included in any of the 16,452 library collections worldwide that share their digital bibliographic catalogues via WorldCat.Footnote 158 It should be noted that the vast numbers of digital-only ebooks produced for children since 2007 raises methodological questions for the study of present-day children’s literature, just as questions are being raised and methods developed within the library sector to catalogue and process self-published items and e-resources.Footnote 159

Once candidates for inclusion were identified, the texts were consulted to check they met the criteria. More than three-quarters of the corpus was purchased. The current low cost of second-hand books, many retailing for a penny online, made this feasible.Footnote 160 Rare and prohibitively expensive texts were consulted while on other academic business to major libraries including The British Library, The National Library of Scotland, The Koninklijke Bibliotheek, and The National Library of Australia. Online versions of texts from digital libraries were extensively used. Digitised versions of twenty-one items were procured using ‘digitisation on demand’ services, mainly from libraries in North America. For example, The Dream Slayer Mystery, Or, the Professor’s Startling CrimeFootnote 161 was digitised within a matter of days, without cost, by Northern Illinois University Libraries (thanks!). Despite this multi-pronged approach, there were twenty books identified that could not be viewed in person: although Legal Deposit Libraries can request copies of all books printed within their jurisdiction, the current situation for library provision of children’s book collections was explained by John Scally, the National Librarian of Scotland:

Over the centuries that legal deposit has been in existence, children’s books have not always been rigorously claimed from publishers, so that there are gaps in the record. Some of the sub-formats within children’s publishing, for example foam ‘bath books’, wall charts, and sticker books have always been collected in a selective manner, while other format types are collected in their entirety but only by geographic region (so, for example, Scotland acquires all school workbooks relating to the Scottish curriculum). In recent decades, as there has been a wider understanding of the importance of collecting children’s literature, the national libraries have worked to fill the gaps retrospectively and today collect texts produced for children across the full range of print and non-print materials in the same way as we collect any other type of literature, and in addition we and other libraries now have special collections of children’s books which provide a rich resource for researchers.Footnote 162

As a result, it can be difficult to find print copies of minor, pre-twentieth century children’s books, even in major national libraries. The twenty potential books that could not be located, many of which were printed in Singapore and Malaysia,Footnote 163 were therefore sadly excluded from the analysis, although they are listed in Appendix C.

3.2 Analysing the Corpus

Once potential books had been identified, they first had to be checked to see if they met the relatively strict criteria for inclusion. Firstly, it became apparent that mentions or illustration of any facet of higher education were for the most part associated with specific fictional characters, meaning the research began to focus on these doctors and professors. Books were checked to ensure they did contain images relating to a fictional academic, keeping the analysis here strictly to fantasy: heavily illustrated books discussing the work of real academics and their research are not included. There is a parallel strand of these texts throughout the history of children’s literature: for example, Victorian texts encouraging curiosity and experimentation, such as The Boys’ Playbook of ScienceFootnote 164 and A Short History of Natural Science: And of the Progress of Discovery from the Time of the Greeks to the Present Day.Footnote 165 More recently, there are many biographies of real scientific figures specifically produced for the children’s literature market. This is a fascinating subgenre, with a variety of picturebook biographies available for leading scientific figures such as Mary Anning,Footnote 166 Albert EinsteinFootnote 167 and Marie Curie.Footnote 168 For this study it was felt that comparing the representation of fictional academics such as Professor Pippy Pee-Pee Diarrheastein Poopypants EsquireFootnote 169 or Professor PigglePoggleFootnote 170 to the accomplishments of world-leading innovators such as Anning or Einstein was simply not appropriate. For an analysis of the portrayal of scientists in children’s science biographies, see Dagher and Ford:Footnote 171 non-fiction texts are often aspirational and can exist as a counterpoint to the biases which are entrenched within fiction, and an analysis specifically of how academics are represented within these would be an obvious future study.

Generic scientists with no academic title or stated university affiliation are not included (which would be another future study). This excludes the likes of the wonderful Mrs Castle, who goes to work as an atomic scientist while her husband stays at home, minds the children and makes plum preserves in Jam: A True Story,Footnote 172 given there is no mention of her academic title or university setting. Medical doctors are not included in the corpus, unless they are noted as carrying out some aspect of university-based research, for example, Dr Dog,Footnote 173 who ‘went to a Conference in Brazil to give a talk about Bone Marrow’Footnote 174, or Doc Eisenbart in Daisy-Head Mayzie,Footnote 175 who thinks that the plant growing out of Mayzie’s head will assist him in getting research funding. Doctor Dolittle also falls into this category,Footnote 176 as he leaves medicine to undertake zoological research (although he is on the very borderline of being included in this study, showing how difficult it can be to set up exhaustive classification frameworks).

Characters that first appear in film, television or video games are excluded: this research focusses on those that originate from children’s texts, rather than in book spin-offs created from other media. This eliminated a variety of material including: books containing Professor Yaffle from the much-loved television show Bagpuss,Footnote 177 the Professor Fizzy cookbooks based on the online series by PBS Kids, Fizzy’s Lunch Lab;Footnote 178 the professors in Pokémon Black and White, a manga cartoon book series based on the Pokémon video game;Footnote 179 and the hundreds of books based around the Pixar film Monsters University.Footnote 180 These are just some of the academic characters found that did not have their genesis in books: an analysis of the representations of higher education in other media marketed to children is an obvious follow-up study.

Characters who appear first in magazines and comics specifically marketed towards a pre-teen audience were included – which meant that professors appearing in Wide Awake (1886), St Nicholas (1888), The Up To Date Boy’s Library (1900), Oor Wullie (Sunday Post 1944), Eagle (1950), Jinty (1977), Toby and See-saw (1977) and Rupert the Bear (1993) feature. Given the importance of children’s magazines and serials to the history of children’s literature,Footnote 181 it seems churlish to exclude them here, and comics have been included in other studies of children’s literature.Footnote 182 However, because of the difficulties in finding content in early comics, it is likely that they are a source of more academics for the corpus, and this shall continue to be pursued in a future study via references in the Grand Comics Database.Footnote 183 Comics marketed towards a young-adult audience and upwards, such as superhero titles, were excluded from the analysis given the complexity of knowing whether this material is age-appropriate (although, without a doubt, many of these comic books are accessed and read by younger childrenFootnote 184).

Books originally written for or marketed towards adults, which may now be commonly thought of as Young Adult Fiction, were also excluded (in particular, the works of Jules Verne fall into this category,Footnote 185 as do those of Arthur Conan Doyle). There are fictional reimaginings of characters that first appear in previously published fiction, with Frankenstein and Frankenstein’s monster (who are often conflated) frequently reimagined as characters in other children’s books; for example, Making Friends with Frankenstein;Footnote 186 The Frankenstein Teacher;Footnote 187 and Robot Zombie Frankenstein.Footnote 188 Given the huge volume of these, just one randomly chosen example is included here for completeness (Dr Frankenstein’s Human Body Book: The Monstrous Truth about How Your Body WorksFootnote 189); likewise, one reimagining of Professor Van Helsing from Dracula (How to Slay a WerewolfFootnote 190) is included. An analysis of how famous literary figures (such as Frankenstein and his monster, or Dracula and Van Helsing) have been repurposed in children’s literature would be a separate study.

Each academic is only counted once in the quantitative analysis, so in the case of a character who appears in multiple books in a series, such as Professor Branestawm,Footnote 191 they are only recorded the first time they appear in illustrated form (which may not be in the first edition of the text: for example, Professor Ptthmllnsprts appears in Kingsley’s The Water-Babies in 1863, but is not illustrated until the 1885 edition; Dr Mary Malone appears in Pullman’s The Subtle Knife of 1997, but is not pictured until the Folio Society Edition in 2008Footnote 192). This concentrated the corpus on when figures were first presented to a childhood readership.Footnote 193 Illustrated books with a Professor or Doctor in the title are included even if there is not an illustration of that individual: it was noted during the course of the research that the academic can sometimes be an absent, omniscient narrator, guiding the reader through a voice of authority (although these texts are in the minority, with only five in the corpus: for example, Professor Miriam Carter in The Mystery of Unicorns, The True History RevealedFootnote 194). Both fiction and non-fiction texts were examined, as fictional professors are often employed as a device of authority to encourage education and instruction in factual texts, as well as being characters in fiction: ambitiously, the full range of books produced as part of the children’s literature market is considered here.

Once the corpus was constructed, all books were read and notes taken on the text. An open coded content analysisFootnote 195 was used to identify and delineate concepts about each academic, including name, gender, age, appearance, subject area, temperament, place of publication etc., using a developing coding scheme to produce label variables that emerged from the data itself as each individual instance was examined. Based on a grounded theory methodology,Footnote 196 this technique assists in the synthesis of large amounts of informationFootnote 197 and can facilitate an efficient and effective summative evaluation of documentary material.Footnote 198 Previous studies have used a fixed coding instrument developed in advance of the analysis of the data: for example, ChambersFootnote 199 developed the ‘Draw-a-Scientist Test’ (DAST), which looked at seven common features of scientists in addition to gender, and this has been adapted and used since by others.Footnote 200 Instead, a coding instrument that could expand to encompass many aspects as the analysis progressed was employed.Footnote 201 For example, as it became clear that gender uniformity was a major issue, the gender of the writer of each text was determined (to the best available knowledge)Footnote 202 in order to ascertain whether there was a correlation between male writers and male protagonists. Working with a large but defined set of texts which did not exceed ‘a single researcher’s analytic capabilities’Footnote 203 meant that this coding methodology was the most efficient for this application. Data were checked and cross-referenced at various intervals, including a complete corpus check at the close of the analysis to identify any duplication or errors, allowing the results to be audited and ‘validated in principle’Footnote 204 even though undertaken by a sole researcher. This analysis was undertaken incrementally from 2014 onwards, and finalised alongside the final list of texts included in 2016, with the write-up undertaken from August 2016 onwards.

Clark notes that, while quantitative approaches such as content analysis provide a valuable tool for feminist and socialist analyses of children’s literature, the limits of positivist methodologies can result in narrow findings under a certain pressure to quantify.Footnote 205 Clark stresses the importance of qualitative methods: ‘it is time for feminist social scientists to do something other than counting as well’.Footnote 206 In this study, quantitative approaches are used in tandem with detailed qualitative analysis, juxtaposing close and distant readingFootnote 207 and treating both illustrations and their surrounding stories as unified texts,Footnote 208 to provide a multifaceted approach to a broad corpus in order to identify and understand its major themes. The broad content analysis allows us to identify trends, and to track and present both individual textual and pictorial examples for closer scrutiny, looking at the ‘complementarity of image and text’Footnote 209 both ‘literally and expressively’.Footnote 210 This is done rather than focussing solely on illustrative techniques employed: given the size and scope of the corpus there is a full range of both monochrome and colour printing processes used, and attention is drawn to the mechanics and features of individual illustrations (given that there can be many pictures of a single character throughout even one book) only when pertinent. Examples of both illustrations and quoted text are woven into the analysis where useful and instructive, to flesh out and describe the findings. Copyright clearance for these was an arduous and expensive process,Footnote 211 undertaken in 2017.

3.3 Conclusion

The gathering and analysis of the corpus presented here was no small task, and required a structured, methodological approach to identify texts that originated as being developed for a child reader (rather than as spin-offs from other media). Taking the time to develop such a stringent framework allows confidence in the resulting corpus of 289 books, while providing the basis for their qualitative and quantitative analysis.

4 An Analysis of Academics in Children’s Illustrated Literature

An overview of the corpus is presented here, tracing the growth of appearance of academics in English language children’s literature over the past 160 years, from the earliest example found until 2014. It is the academics themselves that represent the university sector: very little attention is paid to the institutions or buildings where they work. Using a mixed methods approach, their visual stereotype is explored, showing the domination of the white-haired, old, Caucasian male scientist, while textual clues identify subject area, social class and function within the plot. Academics in our corpus are revealed as loners, and intellect as strange and other, and these factors are juxtaposed with available statistics regarding the university sector, indicating a complex relationship between these stereotypes and the real-life academy.

4.1 An Overview of the Corpus

There were 328 academics found in 289 different English-language illustrated children’s books, which are listed in Appendices A and B. The English-language corpus is international, with the majority published in the United Kingdom (49%) and the United States (41%),Footnote 212 but with texts also from Australia (5%), Canada (2%), India (1%), New Zealand (1%) and one text each from Ireland, Germany, South Africa and Singapore. It is noted that amongst these, some – such as The Water-Babies,Footnote 213 the Dr Dolittle series,Footnote 214 the Professor Branestawm series,Footnote 215 The Famous Five series,Footnote 216 The Chronicles of Narnia,Footnote 217 The Moomins series,Footnote 218 the His Dark Materials seriesFootnote 219 and the Harry Potter seriesFootnote 220 – are more popular and enduring than others – such as Walk Up! Walk Up! and See the Fools’ Paradise: with the Many Wonderful Adventures There as Seen in the Strange, Surprising Peep Show of Professor Wolley Cobble,Footnote 221 The Wisdom of Professor Happy,Footnote 222 Professor Peckam’s Adventures in a Drop of Water,Footnote 223 Professor Fred and the Fid-FuddlephoneFootnote 224 or Vampire Cat, the Phoney-Baloney Professor.Footnote 225

The books were classified given their potential audience’s age range, as catalogued using the MARC 21 bibliographic specification ‘target audience’ 22/006/05,Footnote 226 which indicates whether a book is written for an unknown, preschool, primary, pre-adolescent or adolescent reader. No infant board books containing fictional academics were found.Footnote 227 There are ABC board books about real universities, particularly in the United States, marketed towards ‘alumni, students, and toddling future graduates alike’;Footnote 228 for example, B is for BaylorFootnote 229 and 1, 2, 3 Baylor: ‘Babies and toddlers can get to know Baylor University before they can even speak!’Footnote 230 However, no fictional academics in books for very young children were identified. Additional words have to be associated with the illustrations to indicate academic affiliation (which is a limiting prerequisite of this methodology), and in books designed to develop the vocabulary of very young children it is unlikely that the word ‘Professor’, or other words associated with the university, will be prioritised. Mentions of higher education which are not made in relation to a character such as a Professor or Doctor are very rare.Footnote 231 Only two exceptions to this were found: in the picturebook Baby Brains, the smartest baby in the world is pictured out for a walk in his buggy, pushed by his mum, and ‘On the way home Baby Brains said he wanted to go to university and study medicine’;Footnote 232 in Flix,Footnote 233 the eponymous dog goes to university, as a normal episode of the anthropomorphic life described between birth and becoming a parent himself, although there is high drama as he saves a student from a fire in the female dormitory, whom he then goes on to marry. The university setting here is incidental, although there is an unnamed, pipe-smoking dog in full academic regalia, sitting at a bench. While it would be possible to manually search through children’s picture books looking for visual signifiers of higher education such as this – mortar-boards, gowns and degree scrolls – this is an impossible-to-quantify manual task.

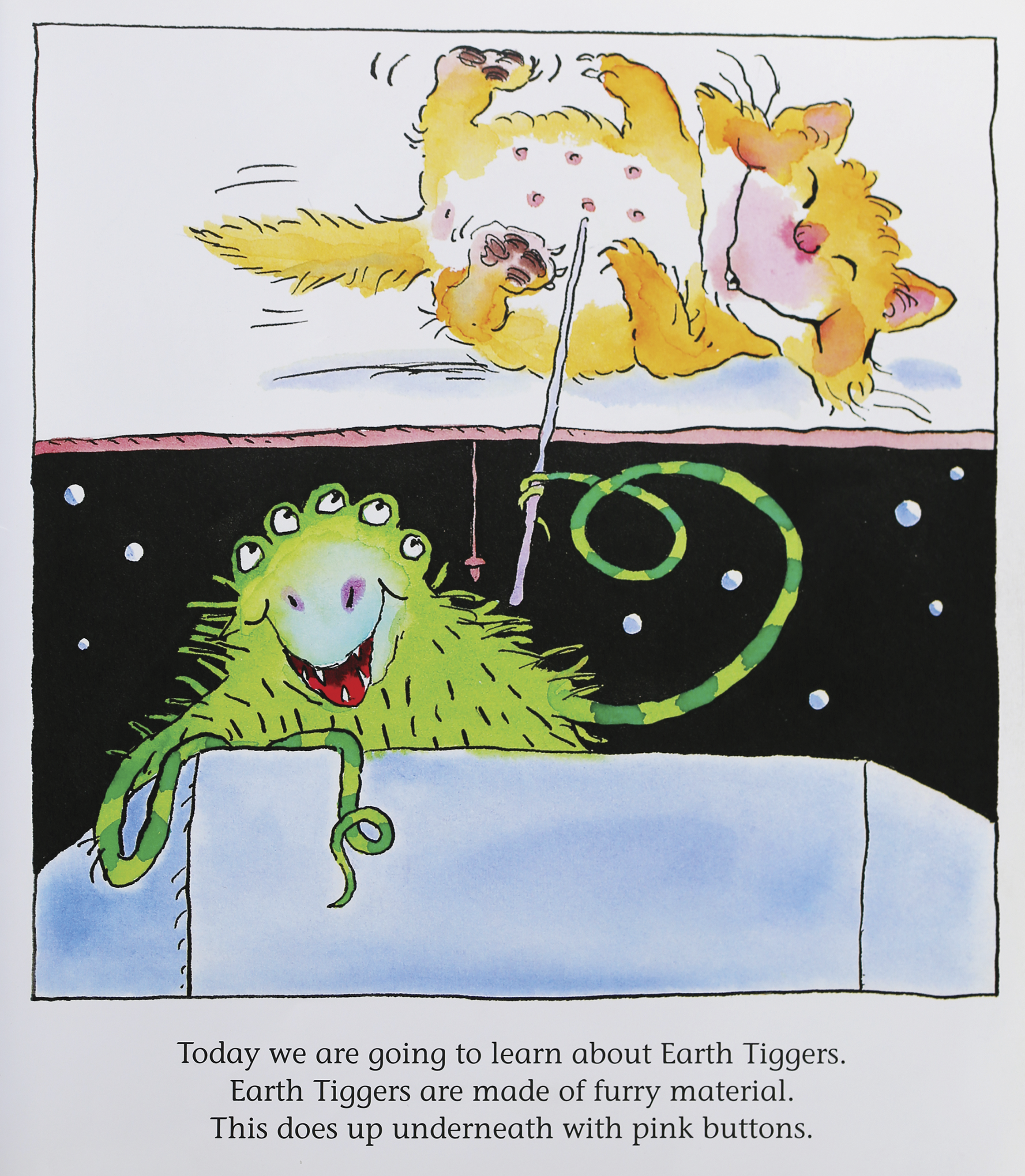

As the target age range of audiences for the books rises, there are more instances of professors: the corpus consists of 22 % Preschool texts (ages 3–5), 33 % Primary (6–8) and 35 % Pre-adolescent (9–11) texts. Understandably, the books move more and more towards full text throughout these stages, with more contextual detail provided. Books marketed towards a 12+ (Adolescent) range make up only 10 % of the corpus, usually having small or occasional illustrated decorations,Footnote 234 and it can be difficult to know where the cut-off point for inclusion in the children’s literature corpus is. The majority of the books are fiction (255, 88 %). There are twenty factual books (7 %) explained by a fictional professor, such as Professor Standish Brewster, professor of Pilgrimology at Plimouth University (sic), who explains the voyage of the Mayflower from Plymouth to the New World in 1620, in Two Bad Pilgrims,Footnote 235 or a sympathetic kingfisher who answers questions about the natural world, agony aunt style, in the Ask Dr K. Fisher series:

Dear Dr. K. Fisher, I’m a rabbit and I would like to know why so many animals want to eat me … Dear Give Peace a Chance, The world is not a perfect place for rabbits, but nor is it for foxes and owls…Footnote 236

There is one cookery bookFootnote 237 and one art and craft manual.Footnote 238 Fourteen books (5 %) are a curious blend of fact and fiction: where a fictional professor explains how the world works, but get it very, very wrong. This is used for comic effect, such as in the Dr Xargle seriesFootnote 239 (this genre will be explored in Section 5), but also to persuade children of the veracity of ideas: seemingly ‘academic’ expertise is used to promote creationism and other religious propaganda, for example in Professor Noah Thingertoo’s Bible Fact Book, Old Testament.Footnote 240

4.2 The Appearance of Professors in Children’s Literature

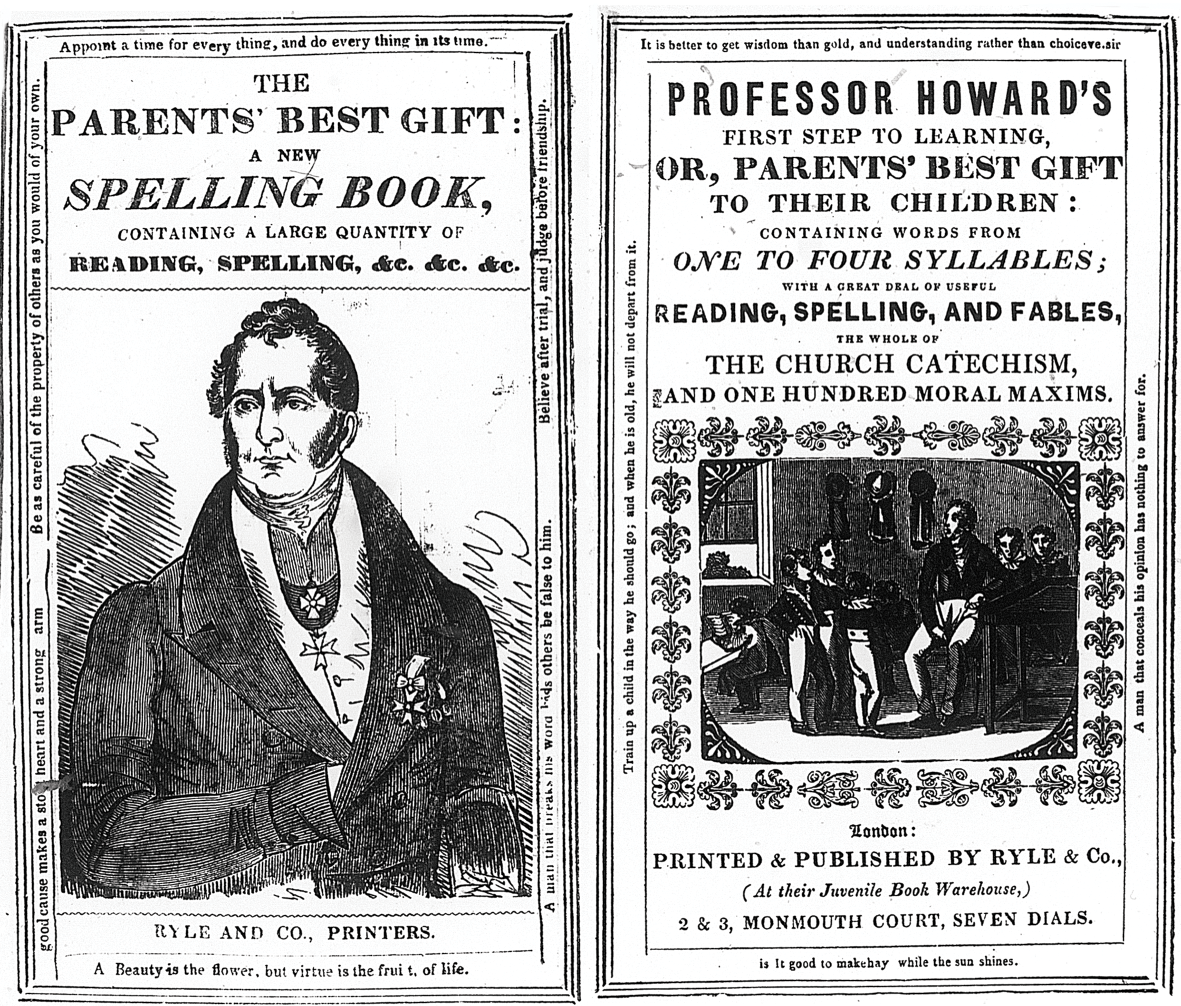

The earliest Professor is to be found in a chapbook primer,Footnote 241 printed circa 1850:Footnote 242 The Parents’ Best Gift: A New Spelling Book, Containing a Large Quantity of Reading, Spelling, etc. with the additional cover title Professor Howard’s First Step to Learning. The content of the primer – as is common for chapbooks – is adapted, reprinted and copied from earlier publications promoting both the Anglican Church catechisms and rote learning of letters and numbers.Footnote 243 The fictional Professor Howard featured within a classroom setting (See Figure 1) is presumably invoked to represent intellectual, academic and social authority as a positioning device to promote and encourage children’s learning (although that authority is directed towards the adult purchasing the book: this primer, in an increasingly crowded market, is the one you should trust). The picture of Professor Howard with his class – reminding us that professors are associated with teaching as well as expertise – is juxtaposed with an ambiguous image on the title page that looks remarkably like Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852). It was common for woodcuts to be reused by early printers,Footnote 244 and often ‘children’s books were built up out of woodcuts lying around in the shop or borrowed from other works’.Footnote 245 This particular untitled image is further used to convey power: it may or may not be our Professor Howard, but this is a book confidently espousing its teaching credentials in a display of male authority and privilege. There is no further mention of the professor within the text, which is a short, fourteen-page pamphlet containing the popular Tom Thumb’s Alphabet,Footnote 246 reading lessons, church catechisms, and ‘one hundred moral maxims’ such as ‘Books alone can never teach the use of books’.Footnote 247

Figure 1 Woodcut illustrations, title page (left) and frontispiece (right) from The Parents’ Best Gift: Professor Howard’s First Step to Learning (circa 1850),.

The use of a Professor in the publication of this fourteen-page pamphlet in the mid-nineteenth century is significant. During this period, children’s education was rapidly changing, becoming more institutionalised with an expansion of the scholastic system (which is reflected in children’s literature of the periodFootnote 248). The new importance of learning resulted in an expanding market for ABC books, chapbooks and primers,Footnote 249 although many of these were ‘numbingly dull compilations of facts and dates which Victorian schoolchildren had to learn by heart in those “catechetical” classes’.Footnote 250 Well-circulating textbooks were printed throughout the nineteenth century that traded on the academic qualifications of the authors as an imprimatur. An 1816 guide for Young LadiesFootnote 251 contains a ‘hypothetical bookseller’s bill’ as a ‘revealing index of what were considered desirable reading habits’:Footnote 252 out of twenty-four (real) texts, three are written by those with higher degrees, and sold as such: Dr Watts’ Improvement of the Mind (first published 1741, with many subsequent editions);Footnote 253 Essays on Rhetoric by Dr Blair (first published in 1784 with many subsequent reprints)Footnote 254 and Dr Mavor’s New Speaker, or English Class Book (1811).Footnote 255 Dr Isaac Watts and Dr Hugh Blair both spent considerable time in the academy and gained qualifications.Footnote 256 However, Dr Mavor is a pseudonym for Sir Richard Phillips, a schoolteacher and bookseller, and the title is presumably used for marketing purposes.Footnote 257 This established mechanism of academic titles being used to frame a text’s trustworthiness crosses over into a recommendation from a fictional professor in our mid-nineteenth century chapbook: indeed, much of the religious text for this chapbook appeared in an earlier format which was promoted by an actual academic figure, Dr William Paley:Footnote 258 Parents Best Gift containing the Church Catechism, Questions and Answers out of the Holy Scriptures. Dr Paley’s Important Truths and Duties of Christianity.Footnote 259 This title, and the habit of using an academic imprimatur to promote texts, indicates a potential trajectory for the switch into fictional endorsement of the reprint of the text in Professor Howard’s First Step to Learning, around 1850. By the late nineteenth century, other authors with professorial titles are selling textbooks, such as Professor Miekeljohn’s Series, one of the first, best-selling standard set of school textbooks in the late Victorian era, written by J. M. D Meikeljohn, Professor of the Theory, History, and Practice of Education at the University of St Andrews and published by Blackwoods from 1883 onwards.Footnote 260

Professors would have become more visible during this period, as the university sector was also transforming, becoming more established throughout the world and playing an increasing role in society, integrating science into a curriculum that had previously eschewed it.Footnote 261 Between the 1860s and 1930s ‘a small, homogenous, elite and pre-professional university turned into a large, diversified, middle-class and professional system of higher learning’,Footnote 262 transforming universities from what had been previously been viewed as an optional phase in the development of privileged young white gentlemen into a core institution informing modern society.Footnote 263 Moving away from their ‘traditional task of serving the older landed and professional elite’,Footnote 264 universities started to adapt to the needs of industrial society. As ‘pressure intensified on parents to invest in education’,Footnote 265 and as the university curriculum became more distinct from secondary schooling, accelerated further by state intervention, we see the forming of an ‘academic profession, which only becomes recognizable as such at the end of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 266 The emergence of ‘the academic’ expert in both research and teaching is itself part of the rise of Professionalism during the Victorian period.Footnote 267

These developments in the university sector, and the growing public perception of academia as a profession, can be coupled with the fact that the nineteenth century was a period where more and more books were being created for a childhood audience, particularly in the United Kingdom and the United States: ‘The latter half of the nineteenth century saw the beginnings of a great age of children’s fiction, an outpouring of literature written by middle-class adults for middle-class children’.Footnote 268 In addition, advancement in printing technology at this time allowed illustrations of higher quality to be produced more easily.Footnote 269 In many ways, the confluence of these factors mean we could only expect an academic to appear fully illustrated in children’s literature from the mid-nineteenth century.

There are forty-one other academics which appear in the corpus in the nineteenth century, all in its last thirty years, with twenty others from the United Kingdom and twenty-one from the United States (see Appendix B, and also the open access anthology which draws together many of these short stories and poemsFootnote 270). It should also be noted, however, that the coverage of books from the United States is influenced by the number of texts appearing in the corpus from the wonderful Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature at the University of Florida, which provides much digitised children’s literature in the public domain: showing how mass digitisation, combined with the constraints of copyright (American texts published in or after 1923 remain in copyright and generally are not digitised and made freely available, but those published prior to that can be without risk, meaning only earlier texts are freely available), can influence the dynamics of corpus-based analysis.

The appearance of professors in children’s literature over this period reflects the growing importance of universities at that time in these contexts, although few characters have anything to do with academic institutions. The Professor in The Professor’s Merry ChristmasFootnote 271 is the first to be included in fiction,Footnote 272 in a Christian retelling of Dickens’ A Christmas CarolFootnote 273 two children are illustrated delivering food to a poor, elderly professor who has decided not to celebrate Christmas, until shown visions of families, charity and the second coming. There is a showman (Professor Wolley Cobble, in Walk Up! Walk Up! 1874), American coming-of-age tales of hard-working students and young professionals (Herbert Carter’s Legacy, or, The Inventor’s Son,Footnote 274 Professor Johnny,Footnote 275 Professor PinFootnote 276 and a thrilling adventure in the The Professor’s Last Skate,Footnote 277 where a teacher recalls to his students the last time he went skating alone, years ago: breaking his leg and having to haul himself miles home across the ice). Many of the early professor’s in the corpus are indistinguishable from higher-level school teachers, showing both the changing linguistic use of the term and also the formalisation of academic training: for example, the Old Professor in the Princess of Hearts,Footnote 278 draughted in unsuccessfully to deal with a precocious royal child. More random stories do start to appear: the grotesque Professor Menu is a ‘celebrated experimental cook, who had been driven away from London because of the effect of his awful experiments on the digestions of the customers at his restaurant!’,Footnote 279 discovered on an island by starving shipwrecked sailors, but whose worrying scientific experiments on food drive the narrator ambiguously to madness, or a confession, it was all a tall tale.

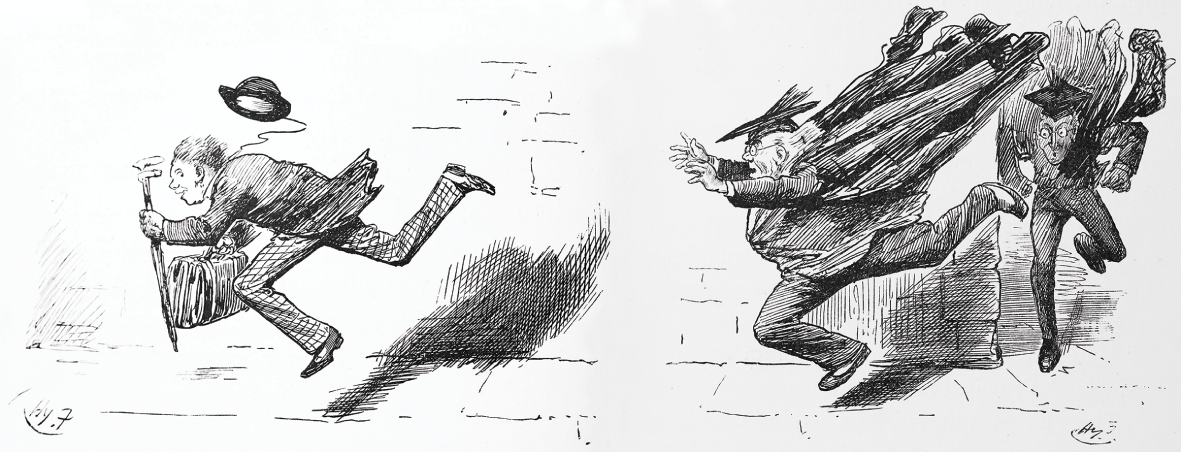

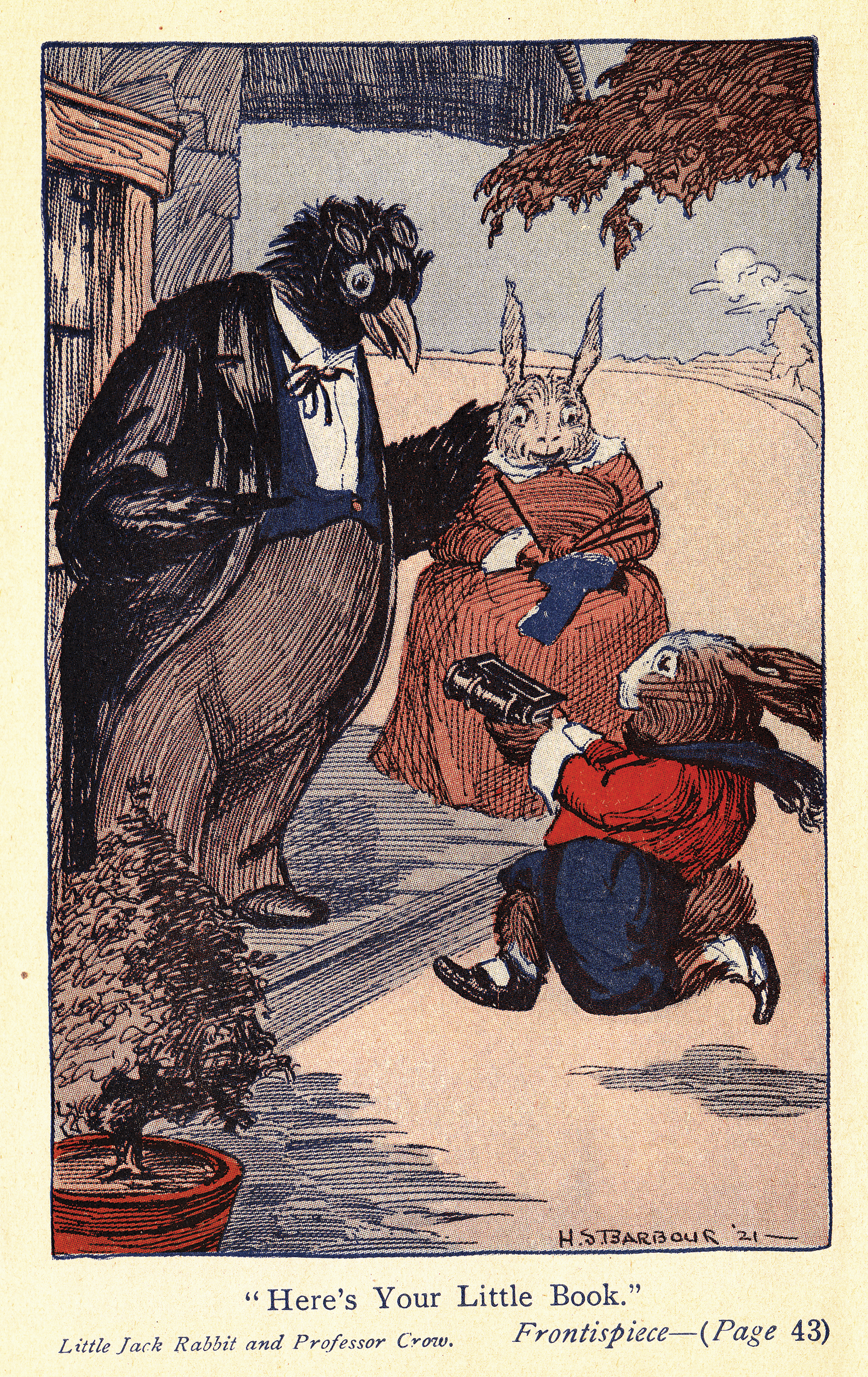

An early colour illustration (Figure 2)Footnote 280 appears in the fairy tale Professor Bumphead,Footnote 281 which publishes a lecture given by the fairy professor, on the setting up of a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Inanimate Objects (stressing the ridiculousness of professorial advice, at this early stage, mocking Victorian scholarly and scientific societies): ‘A few well-chosen words addressed to a gate-post, flower-pot, bottle or any other inanimate object, will cheer its heart and encourage it to get through the terrible monotony of its existence’.Footnote 282

Figure 2 Professor Bumphead lecture tells us how miserable windmills are. In The Fairies’ Annual (Johns, The Fairies’ Annual, p. 31). Every effort has been made to trace any right-holder who may own the rights to this work (the estate of Cecil Starr Johns, and The Bodley Head), although it is believed to be in the public domain: any further information is most welcome in order to remedy permissions in future editions.

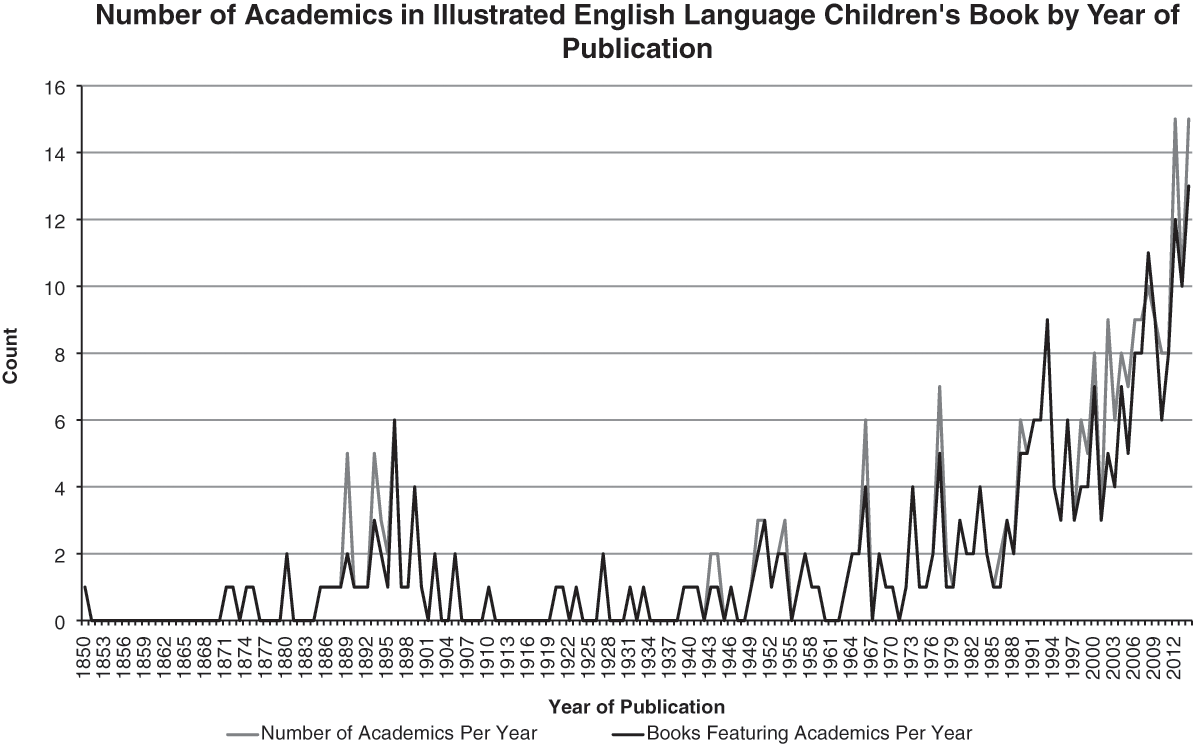

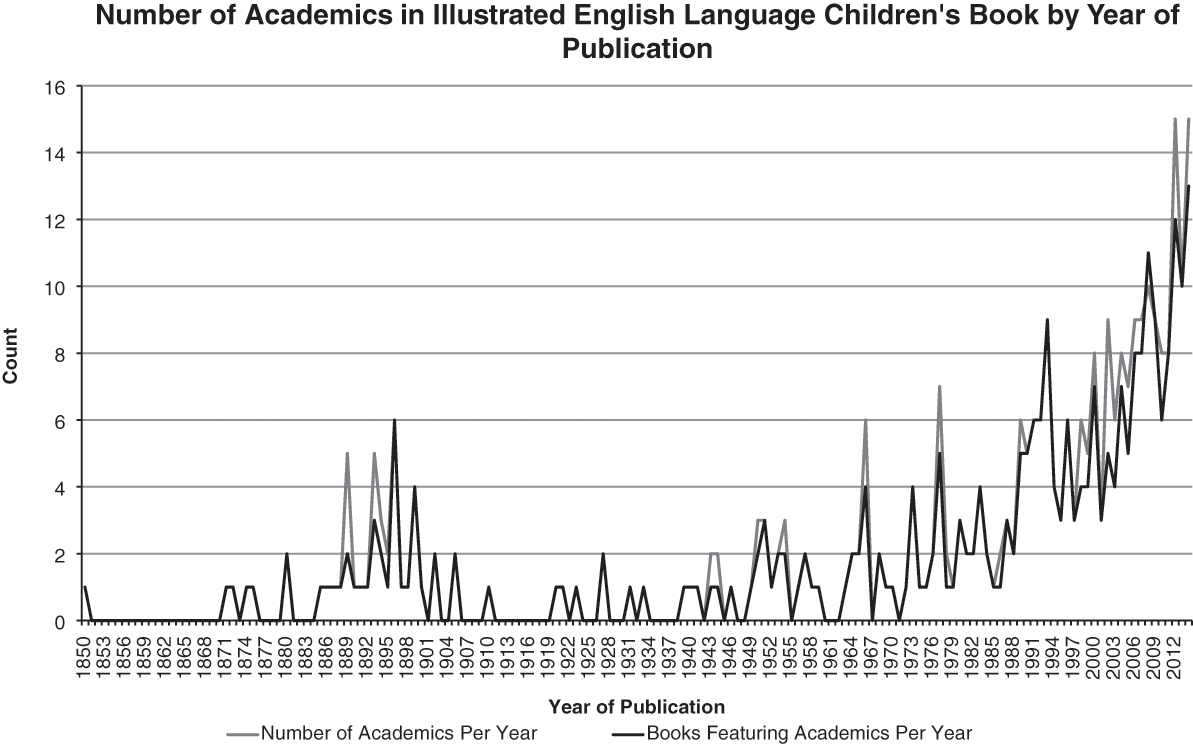

Early professors in children’s literature cover a range of tales and genres, symptomatic of the first one hundred years of the corpus, where there are sixty-eight academics found (thirty-eight being from the United Kingdom, with thirty from the United States). There is a warning tale of a conman and magician (Professor De Lara),Footnote 283 advice on healthy living (The Wisdom of Professor Happy),Footnote 284 a scientific quest in Professor Peckam’s Adventures in a Drop of Water,Footnote 285 and an anthropomorphic short story in the style of Beatrix Potter (Professor Porky the Porcupine).Footnote 286 The most enduring characters of this period are the scientist Professor Ptthmllnsprts in Kingsley, The Water-Babies, the doctor turned zoologist Doctor Dolittle,Footnote 287 and the baffled scientist and inventor Professor Branestawm,Footnote 288 giving three best-selling blueprints for scholarly conduct in children’s literature. There are two spikes Chart 1, which shows the date of publication of books in the corpus: the first towards the end of the nineteenth century shows both the growing awareness of the university sector and also the effect of full text search in public domain mass digitisation on the process of corpus building. Instances fall away once manual searching of print takes over in early twentieth-century texts, before rising again. It is only from the mid-twentieth century that academics in children’s books gain in popularity in this dataset, becoming more prevalent (or, at least, easier to find) and settling down into established stereotypes.

Chart 1 Academics appearing in English language children’s books per year since 1850. Note, in some books, more than one academic may be featured: therefore the number of books in which they appear per year has been noted, as well as the total number of academics found per year.

It is tempting to relate the growth of the number of illustrations of academics found in children’s books per year across in the second part of the twentieth century to the rapid expansion of and increased access to higher education throughout the English-speaking world within that period.Footnote 289 For example, in the United Kingdom, the number of universities more than doubled in the latter half of the twentieth century, and the population’s ‘overall participation in higher education increased from 3.4% in 1950, to 8.4% in 1970, 19.3% in 1990 and 33% in 2000’.Footnote 290 However, the growth shown in Chart 1 does not necessarily correlate to this; nor does it mean that academics are becoming more important as a theme in children’s literature and appearing in a higher percentage of texts.

The growth in the corpus can be plotted against known data on book production from two library catalogue sources. Firstly, counts of all books catalogued as English language for a junior audience in WorldCat were manually scraped from the site.Footnote 291 Given it is so difficult to ascertain reliable statistics for book publications over time,Footnote 292 WorldCat remains a useful resource for quantitative analysis despite its known limitations.Footnote 293 There are 1781 books in WorldCat that were catalogued as being English-language juvenile-audience text published in 1856, 1574 in 1906, 8082 in 1956 and 50,477 in 2006 (concluding the period prior to the exponential growth of self-published books, many of which do not feature in library catalogues). Secondly, The British National Bibliography (BNB),Footnote 294 which has been recording the publishing activity of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland since 1950,Footnote 295 was contacted and asked for a list of children’s books published in the United Kingdom, which had been included in the BNB since its inception, and which they began cataloguing in 1961 given changing cataloguing conventions.Footnote 296 However, it should be noted that the division between children’s and adult books is not often clear within the catalogue,Footnote 297 and there is yet to be a special edition of the BNB listing only children’s books, given books for children and books about children are often hard to distinguish within the ‘juvenile literature’ heading (this is an area ripe for community input, to crowdsource a national bibliography of children’s fiction and non-fiction literature). There are currently 1033 juvenile literature books in the BNB catalogued as being published in 1970, 2912 in 1980, 3653 in 1990, and 8938 in 2000. To allow comparison between WorldCat and the BNB data, the volume of books catalogued as juvenile literature published per year is expressed as a percentage of the total books in each individual series, indicating that more books are produced towards the end than the middle of the twentieth century.

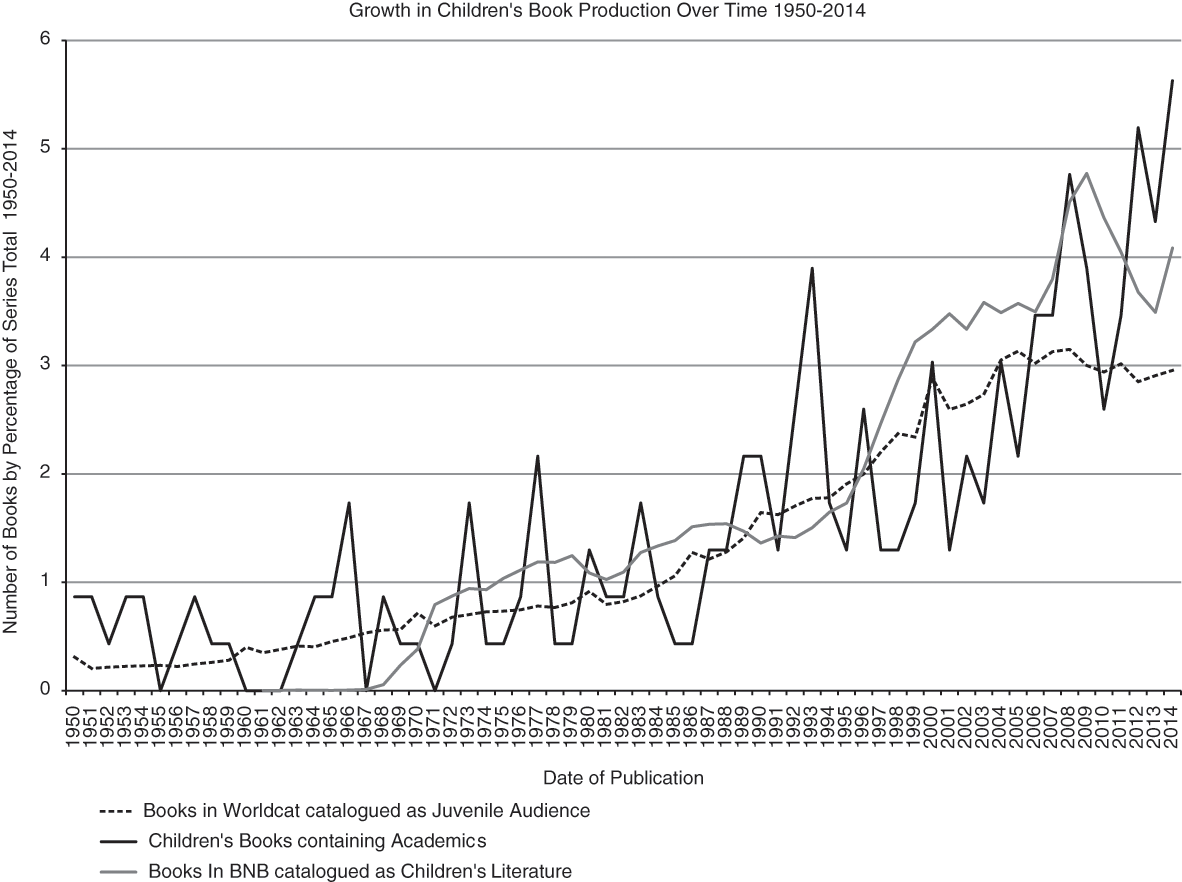

Chart 2 shows growth in the number of children’s books appearing in the BNB and in WorldCat, year on year, from the mid-twentieth century: more books classified as juvenile literature are produced yearly. The WorldCat data (from 1850) comprises of over 1.6 million books, the BNB data (from 1961, where books published in England and Ireland were first catalogued as Children’s Literature in the BNB) contains just short of 270,000 records (although there may be some false positives in this dataset, with books for children as subject being conflated with books for children as audience, so further cleaning and statistical work is needed on this dataset). Our corpus of 289 books in comparison shows a much more volatile trajectory, being more sensitive to the addition of one or two texts per year. However, all show upward trends, indicating that despite the growth of the university sector, the increase in the number of academics is correlated with the fact there are simply more and more children’s books being produced in the second half of the twentieth century, rather than the topic becoming more important and prevalent in juvenile literature over time (which would be represented by curve that deviated further from the BNB and WorldCat series in Chart 2). The percentage of texts which feature an illustration of an academic (calculated by the total books per year, and the books catalogued, as above, in WorldCat or the BNB – provided all possible examples have been found, which is rather unlikely!) is roughly constant. Using the BNB introduces interesting methodological opportunities for the study of children’s literature (or ‘juvenile literature’, as it is described as a topic in the Library of Congress Subject Headings used by the BNB) but requires a robust methodology to be developed to mitigate against statistical uncertainty. The BNB and other national bibliographiesFootnote 298 are, as yet, an untapped dataset for children’s literature scholarship, and hold future potential for evidence-based quantitative research on the topic, provided the datasets can be further cleaned and moderated in a way which would establish them as authoritative data sources for children’s book publishing.

Chart 2 The growth in book production over time, by publication year. The number of children’s books published that contain professors is compared to two available data sources: total number of books catalogued for juvenile audience in WorldCat, and books catalogued as ‘juvenile literature’ in the British National Bibliography. The x-axis represents the percentage of books published in that one year, in comparison to the total number of books published for that series between 1950 and 2014 (the series total reaches 100 %, so in the case of WorldCat we can see that 0.5 % of books classified as juvenile literature in WorldCat are published in 1950, but 3 % in 2004: the number of children’s books produced over time rises year on year). In all three series, proportionally more books appear across the end of the twentieth century, suggesting that there are more children’s books being published in total (which, in addition, are more likely to be catalogued in the modern library environment; see quote from Scally in Section 3.1), not that academics in children’s literature are becoming proportionally more prevalent.

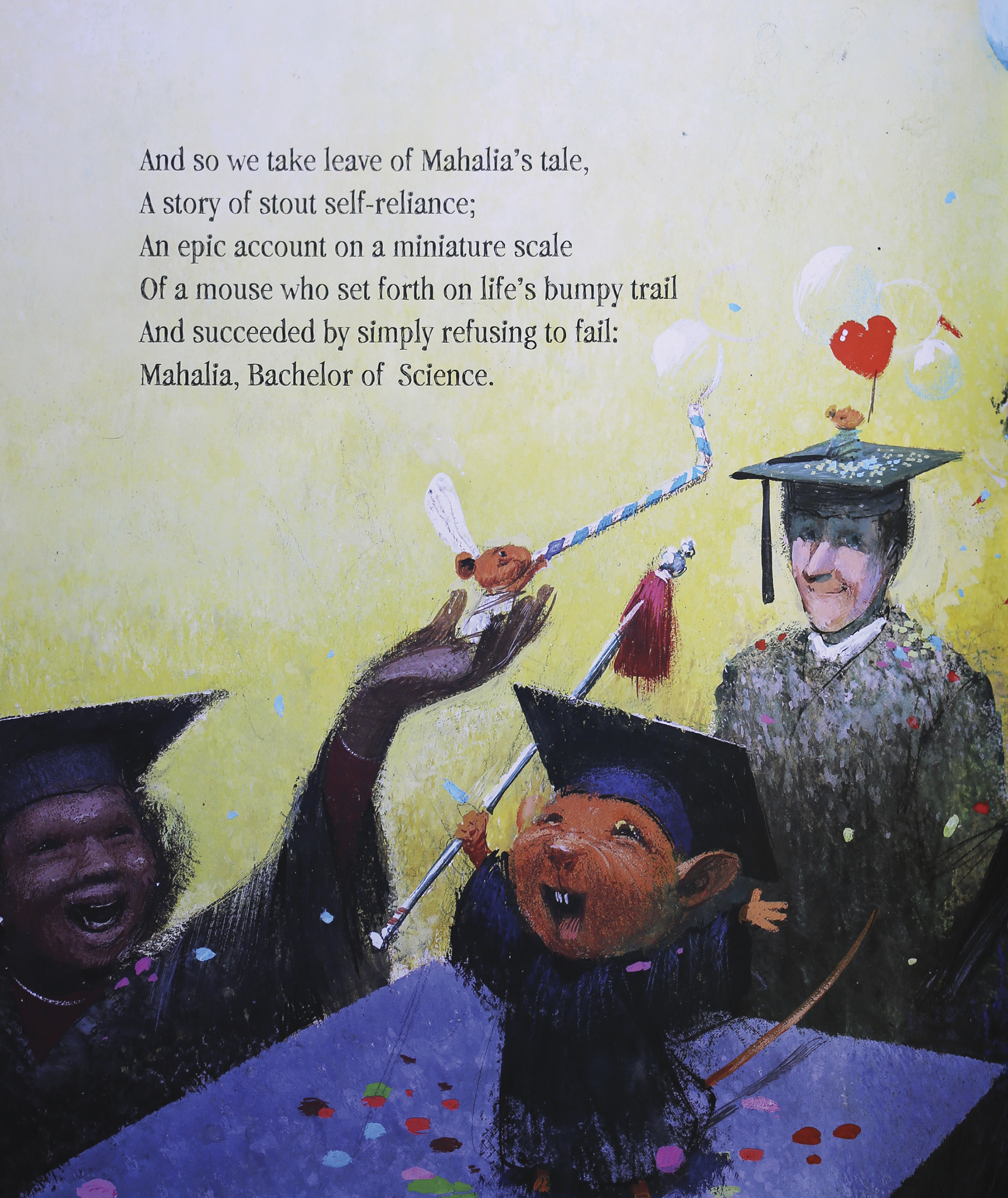

The increase in number of books in the corpus towards the close of the twentieth century does mean that 50 per cent of the academics first appear in books published from 1993 onwards, and will therefore reflect modern representations of academia, once tropes have had a chance to develop, in a form which ‘declares its debt to postmodern modes of production’ with ‘the rise of the experimental, multi-voiced, metafictional children’s text in the latter half of the twentieth century’.Footnote 299 The prominence of academics in enduring and popular best-selling children’s texts means that their influence goes far beyond this relatively low occurrence in the pantheon of children’s literature, with ‘famous’ academics in children’s literature both building and reinforcing the stereotypes used by subsequent authors and illustrators as blueprints and shorthand for their characters. Overall, distinct themes emerge which become constant: universities as places or institutions are not as important as the people within them, and fictional academics have stereotypes that emerge involving gender, race, class, age, appearance and academic subject. These – and the dominant stereotypes that emerge – will be explored and placed into context via their external influences. Drawing on trends and stereotypes that came before them in often ‘playful subversion’,Footnote 300 as the stereotype of the mad male muddlehead coalesces, it can become both easier to drop a character into a children’s story without need for explanation as part of intertextual exploration, and harder for writers and illustrators to confront and break free from these expected mores.

4.3 The Presence and Absence of the University

It may be thought obvious to look first at how universities are pictured as settings in children’s literature. However, after reading and analysing the corpus, it became clear that any analysis should concentrate on the individuals that appear in the books, both as protagonists and minor characters, rather than the representation of universities as places or institutions: there is so very little comment on anything other than the people in the texts, either in text or as background setting in illustrations. This is unlike school stories, where ‘the school features almost as a character itself’,Footnote 301 or the analysis of universities in American superhero comics where the leafy green park life spaces of campus ‘connect with and bolster public imaginings of U.S. institutions of higher education’.Footnote 302