Successful healthcare organisations have always been built on the engagement and leadership of medical staff, and the need for this will never be greater than in the demanding times ahead. The National Health Service (NHS) context is challenging; leaders in both health and social care are facing huge change. Many organisations are not only new but are also (in England) about to confront further change following the NHS White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS (Department of Health 2010). New ways of working and new relationships are continually and rapidly evolving, but a constant remains: the understanding that the most important asset of any organisation and the key to its success is its staff. It seems highly likely that the organisations that survive and thrive will be those that understand what leadership means and that focus on the development and nurturing of their leaders.

Mental health services will face particularly difficult challenges, because they straddle healthcare, primary and acute care, as well as social care, which is itself subject to change and even more stringent budget restrictions. It is the responsibility of all concerned, including the Royal College of Psychiatrists, its members and medical educators and leaders, to underline the importance of the leadership role and the time and resources required to develop and maintain high-quality leadership skills in current and future psychiatrists.

Background

Medical leadership and its competencies have attracted much attention of late. The General Medical Council (GMC; 2011) states that it is a core requirement for all doctors to work effectively with colleagues and, in common with the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2009), refers the reader to the GMC guidance Management for Doctors (2006). This states that doctors in managerial positions (which are not defined) must demonstrate leadership skills. In the Medical Leadership Competency Framework, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges state that ‘doctors have a legal duty broader than any other health professional and therefore have an intrinsic leadership role within healthcare services’ and that doctors ‘have a responsibility to contribute to the effective running of the organisation in which they work and to and its future direction’ (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010: p. 6). Sir John Tooke, in Aspiring to Excellence (2008), concluded that ‘the leadership role of medicine is increasingly evident’.

The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement commissioned the Enhancing Engagement in Medical Leadership project (www.institute.nhs.uk/building_capability/enhancing_engagement/enhancing_engagement_in_medical_leadership.html) to examine the meaning and use of the term ‘medical engagement’, empirical evidence linking such engagement to organisational or clinical performance, and approaches to quantitative measurement of engagement (and, if there were none, to suggest some). This work led to two key UK publications: a literature review on the engagement of doctors in leadership (Reference Dickinson and HamDickinson 2008) and a document examining whether the engagement of doctors truly influences the performance of healthcare organisations (Reference Hamilton, Spurgeon and ClarkHamilton 2008).

These works describe how, since the early 1980s, the NHS has become more centralised while requiring doctors to become more accountable for making local decisions via clinical directorates and other mechanisms. The evidence shows that doctors can confound imposed top-down change, whereas engaging them with any change process can lead to clear improvements in performance, including clinical performance. The evidence suggests that the complex nature of healthcare organisations means that leadership is required not just at the top of the system but distributed throughout and that team leadership of microsystems can achieve high levels of performance throughout the organisation if lower-level leadership aligns with the top (Reference Dickinson and HamDickinson 2008; Reference Spurgeon, Barwell and MazelanSpurgeon 2009, 2011). Importantly, where major change programmes are undertaken, leaders at different levels are needed and they need to be closely connected. Interestingly, these reviews found the question of definition of medical leadership and engagement hard to pin down. One of the leading theorists in UK public services suggested that:

‘leadership has experienced a major reinterpretation from representing an authority relationship (now referred to as management or transactional leadership […]) to a process of influencing followers of staff for whom one is responsible, by inspiring them, or pulling them towards the vision of some future state […]. [T]his model of leadership is referred to as transformational leadership because such individuals transform followers’ (Reference Alimo-MetcalfeAlimo-Metcalfe 1998: p. 7).

This model, which is essentially concerned with influencing others rather than exerting authority in a traditional sense, seems to fit well with healthcare systems, and doctors in particular, and suggests that leadership is ultimately a social function.

What emerges is a model of leadership operating at three levels (Reference Mohapel and DicksonMohapel 2007):

-

• leadership of self (the ability to change oneself)

-

• leadership of others (teams; formal, structural leadership positions and informal influential positions)

-

• leadership of organisations (strategic leadership).

This clearly suggests that leadership, if it is about the process of influence, extends far beyond those in formal or hierarchical positions and includes everyday clinical practice. This means that all doctors have a leadership role and will need to attend to the development and maintenance of knowledge, skills and behaviours for leadership in their personal development plan throughout their career in the same way that they maintain their clinical knowledge and skills. The challenge for writing and implementing curricula with appropriate methods for learning and assessment is therefore considerable.

Curriculum

Following some of the above work and reviews of evidence, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, in collaboration with the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, published the Medical Leadership Competency Framework (MLCF), now in its third edition (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010), and the associated Medical Leadership Curriculum (MLC; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2009). One criticism of the MLC is that, on occasion, it includes leadership matters that are often seen as managerial. It suggests that running the service is just as much a leadership task as is strategic planning. This tendency to conflate leadership and management, while attractive to some, is for others confusing and can lead to difficulties in guiding learning. The MLCF is expected to direct curriculum development in the domain of leadership across all stages of medical education, from undergraduate to the first 5 years of continuing practice. The MLC is intended to guide the acquisition of appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes in postgraduate training. It outlines a structure based on the five domains of the MLCF (Box 1), each containing four elements under which the expected competency outcomes are described with suggested methods of learning.

BOX 1 The five domains of the Medical Leadership Competency Framework

-

1 Demonstrating personal qualities

Developing self-awareness

Managing yourself

Continuing personal development

Acting with integrity

-

2 Working with others

Developing networks

Building and maintaining relationships

Encouraging contribution

Working within teams

-

3 Managing services

Planning

Managing resources

Managing people

Managing performance

-

4 Improving services

Ensuring patient safety

Critical evaluation

Encouraging improvement and innovation

Facilitating transformation

-

5 Setting direction

Identifying the contexts for change

Applying knowledge and evidence

Making decisions

Evaluating impact

Following the publication of these two documents, each medical Royal College was asked to ensure that their postgraduate curricula include the competencies described in the MLC. The Colleges were also asked to produce resources to support the learning of MLC competencies in their specialty and subspecialty training programmes.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists (2009) places great emphasis on the need for consultant psychiatrists to display management and leadership skills. This is reflected in the curricula that the College has published since 2007. The competencies in management and leadership contained in the MLC can be tracked in the current versions of the College curricula.

The learning outcomes of the current curricula for psychiatry specialist trainig are built on the CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework (Reference FrankFrank 2005), which groups the intended learning outcomes to be acquired during training around seven physician roles, as described in Table 1.

TABLE 1 The physician roles and intended learning outcomes of the psychiatry curriculaa

The MLC competencies are contained within 8 of the 18 intended learning outcomes of the psychiatry curricula (outcomes 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17 and 18). As well as the outcomes under the role of ‘doctor as manager’, there are relevant outcomes under the roles of ‘doctor as collaborator’, ‘doctor as scholar’ and ‘doctor as professional’.

In response to the call to produce resources to support the learning of MLC competencies, the College Curriculum Committee commissioned a group of medical managers and educators to produce a study guide in management and leadership for advanced psychiatry trainees (Reference Brittlebank, Briel and RichardsonBrittlebank 2011), which is described in the next section.

Reference Alimo-Metcalfe and BradleyAlimo-Metcalfe & Bradley (2009) have criticised reliance on competency frameworks for organising training in leadership on empirical grounds, based on their review of the evidence supporting the validity of the approach and their work with the London Deanery. They argue that the competency-based approach may be too formulaic and the basic assumption of combining competencies to make a whole may be too simplistic, particularly as it may fail to address key behavioural components and the linking of behavioural competencies with other competencies in the construction of performance. During their 3-year longitudinal research into transformational leadership in the NHS, they found that leadership behaviours are more important than leader competencies in determining team effectiveness. This was in line with the findings concerning engaging leadership, which stressed the importance of a culture of engagement in high-performing teams and organisations (Reference Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-MetcalfeAlimo-Metcalfe 2008a). These findings underline the importance of ensuring that the methods used for the training and assessment of leadership performance are as authentic as possible and emphasise the behavioural and attitudinal components of performance.

Methods of learning, teaching and assessment

Location and experience

As methods of learning, teaching and feedback need to be authentic, it is clear that activities to support leadership training must be located as closely as possible to the trainee's workplace. This seemingly small point about location is to make the essential shift from competence to performance by centring learning on real experience. Research into the ways that professionals learn has shown the importance of learning through experience and the need for programme designers to maximise the learning provided by their own workplace (Reference Cheetham and ChiversCheetham 2001). The models of learning used in the College Study Guide (Reference Brittlebank, Briel and RichardsonBrittlebank 2011) are, therefore, based on adult learning and social learning theories.

The College Study Guide

The Guide includes specific references to influential works on adult learning and experiential learning theories (Reference KnowlesKnowles 1980; Reference KolbKolb 1984). It advises trainees to become aware of their learning style by assessing their learning preferences using Honey & Mumford's Learning Styles Questionnaire (Reference Honey and MumfordHoney 1992). Trainees and trainers are encouraged to plan learning activities that take into account the trainee's preferred learning style. In line with current recommendations about workplace learning (Reference Morris, Blaney and SwanwickMorris 2010), the Guide also makes use of social approaches to learning by explicitly engaging supervisors and mentors as role models and guides, and seeking to embed the trainee's learning experience in meaningful projects that will influence others and change practices.

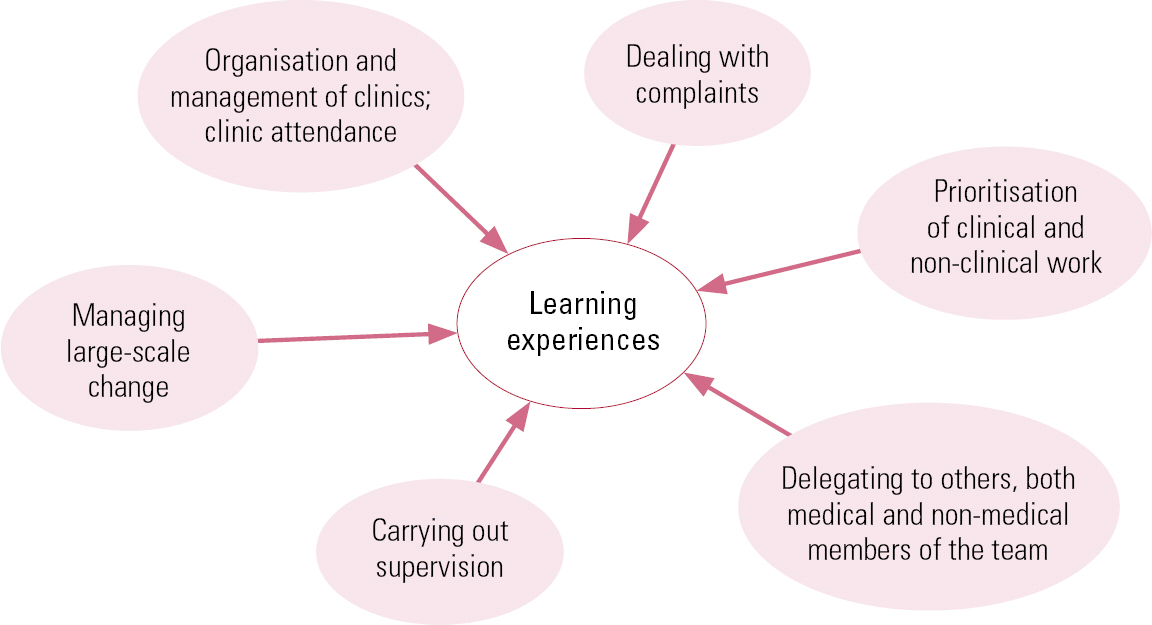

The content of the Guide is based on six ‘learning experiences’ that may take place during advanced psychiatric training (Fig. 1). Five of the experiences were derived from areas of major learning needs identified from a study of psychiatry trainees and newly appointed consultant psychiatrists in the Northern Deanery of England (Reference Briel, Linsley and StevensonBriel 2004). The sixth learning experience is managing and leading change. The learning experiences are mapped onto competencies in the MLCF and may also be mapped onto competencies in the relevant psychiatry curriculum.

FIG 1 The six learning experiences in advanced psychiatric training (Reference Brittlebank, Briel and RichardsonBrittlebank 2011).

The first five learning experiences can be completed within 12-month placements. The sixth requires the trainee to participate in a longer-term change project, so the trainee will work in more than one post in a higher training programme while completing the project.

Before beginning a Study Guide learning experience, the trainee is encouraged to go through a four-stage process to plan their learning. This helps the trainee to establish where they are, where they are trying to get to and how to bridge the gap. (Box 2 gives an example of this process, along with the subsequent stages in the learning process.)

BOX 2 Example of a learning need – dealing with complaints

Stage 1: Identifying the learning need

Early in the placement, the trainee identifies that they need to develop the competency for dealing with concerns and complaints. This should be timetabled into their learning plan.

Stage 2: Putting the process in place; obtaining relevant knowledge (ensuring the learner knows)

The trainee and trainer agree that the trainee will manage a complaint to develop competency in this area. The consultant discusses this with the service to ensure that it is happy with the arrangement. Supported by the trainer, the trainee will consider what further reading or courses are needed before attempting to manage a concern or complaint in practice. For example, the trainee may wish to read GMC guidance or Royal College and Deanery advice; healthcare providers also have policies of which the trainee should be aware. The LeAD medical leadership e-learning resource (www.e-lfh.org.uk/projects/lead/index.html) has materials that may be of use. Time should be spent in supervision sessions, discussing how the trainee's organisation approaches the management of complaints.

Stage 3a: Trying skills in practice (concrete experience)

The trainee and trainer identify a concern or complaint that the trainee can handle to gain concrete experience. For example, the trainee might deal with a minor concern in their healthcare provider complaints-handling department, or spend time with a local Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) to observe how it deals with a concern about a poor patient experience.

Stage 3b: Reflecting on practice individually (reflective observation)

The trainee should then complete a reflective diary on their initial thoughts about how they or the PALS would manage the concern/complaint. In their reflection, the trainee should try to address the following:

-

• understand the difference between a concern, an informal complaint and a formal complaint

-

• understand the difference between a concern about an individual and a concern about a process

-

• how to deal with concerns about oneself

-

• how to deal with concerns about others – this is a good topic for a case-based discussion

-

• understand the role of service mangers in dealing with concerns and complaints and how to work constructively with managers in dealing with complaints

-

• how concerns and complaints feed into the appraisal process.

At this point the trainee may want to look again at the module on root cause analysis in the LeAD medical leadership e-learning resource.

Stage 3c: Reflecting on practice with trainer (abstract conceptualisation)

The trainer and trainee discuss the reflective diary and develop ideas for how the trainee should respond to the concern/complaint. This may include the use of the PALS, the healthcare provider's complaints process and online resources such as the NHS Choices website (www.nhs.uk).

Stage 3d: Demonstrating skills in practice (active experimentation; ‘shows how’)

This stage involves the trainee and trainer reviewing how the trainee addressed a minor concern or what the trainee learned from watching PALS deal with a concern about a poor patient experience. This may involve the trainer observing the trainee conducting an interview with the complainant. The trainer will probably take notes so as to provide useful feedback.

Stage 4: Review and document achievement

In reviewing how the trainee responded to a complaint, the trainer will ask them to consider how the session went. The trainer will provide feedback on the session, starting with general positive points. The trainee may, however, wish to return to the discussion at a later date, after having had opportunity to reflect on it more.

Once the trainee and trainer feel that the most has been made of this learning experience, the trainee should complete a reflective diary. The trainee is prompted to concentrate on how they approached this task as a professional, how they made certain that the complainant was informed about the resolution of the complaint and what approaches were used to ensure that organisational learning took place. This will make sure that the trainee achieves the intended learning outcomes. The trainer will complete a Direct Observation of Non-Clinical Skills assessment relating to some aspect of the learning experience, which the trainee will add to their portfolio.

(Adapted from Reference Brittlebank, Briel and RichardsonBrittlebank 2011)

Stage 1: Establish learning need(s)

At the beginning of each placement in their higher training programme, the Guide encourages trainees and trainers to jointly identify which of the learning experiences should be undertaken in the placement. The Guide includes a self-assessment tool that helps trainees to be aware of their learning needs in the domains of leadership and management. This knowledge is used to help the trainee decide what learning needs will be met by working through the learning experiences that have been identified for the placement.

Stage 2: Set objectives with timescales

The second stage of the planning process is for trainee and trainer to set out the learning objectives that are to be achieved. The Guide supports the use of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-limited (SMART) objectives. The timetable for addressing the objectives should also be set out in the learning plan.

Stage 3: Agree and implement the methods by which the objectives will be met

The next stage is for the trainee and trainer to agree and implement the methods that will be used to achieve the objectives. The Guide explicitly directs trainees to ensure that the learning methods used will address all aspects of the learning cycle and that methods of gaining feedback and evaluation are built into the learning programme.

Under the heading of ‘concrete experience’, the Guide indicates that trainees should examine current practice in the area of work that the learning experience addresses. For example, as part of the learning experience ‘organisation and management of clinics’, it suggests that trainees critically review a month's experience of out-patient clinics. The trainee should look at how the clinics were organised and how appointments were allocated, and think about the patient's experience.

The concrete experience stage leads to the ‘reflective observation’ stage. Here, trainees are encouraged to look at different ways to organise clinics, to compare these with published guidelines and to discuss their findings with their trainer.

The Guide supports the ‘abstract conceptualisation’ stage of the learning cycle by asking trainees to plan small-scale local improvement projects to address the shortcomings that they have identified. The trainee's thinking in these areas can be supported by guided reading and by e-learning resources. The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges in partnership with the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement has produced a set of e-learning resources intended to support the Medical Leadership Curriculum. The LeAD medical leadership e-learning resource comprises more than 50 interactive, peer-reviewed modules and is freely available to NHS employees in the UK from e-Learning for Healthcare (www.e-lfh.org.uk/projects/lead/index.html).

Trainees are advised to implement their small-scale projects as part of the ‘active experimentation’ stage. The Guide advises trainees to incorporate methods of evaluating their project in each stage of its implementation through gathering feedback from patients and other stakeholders, as well as gathering organisational data.

Stage 4: Review achievement

The fourth stage of each learning experience is the formal assessment and documentation of the learning that has been achieved.

In the Study Guide, the principles of assessment in leadership are outlined by reference to Miller's pyramid (Reference MillerMiller 1990). Miller's pyramid is used in medical education to help understand how medical competencies, performance and their assessment fit together. In this model, competencies are arranged hierarchically, in that lower levels must be mastered before the higher ones, as below:

-

1 Do you have knowledge about a subject, but have not yet started to think about how to apply this knowledge? (‘Knows’)

-

2 Have you thought about how to apply this new knowledge and have strategies in place to do this? (‘Knows how’)

-

3 Have you demonstrated the skills in practice? (‘Shows how’)

-

4 Do you regularly use this competency in routine practice? (‘Does’)

Ideally, there should be assessments at every level of the pyramid. The e-Learning for Healthcare modules described earlier incorporate tests of the knowledge that trainees should acquire. Therefore, successful completion of modules can be documented as achievement of the ‘Knows’ stage. The ‘Knows how’ level may be assessed by the trainee's supervisor in the course of a conversation about how knowledge may be put into practice. For example, a trainee may talk about linking quality-improvement theory with observations of practice at other settings with thoughts on their own practice context and systems. The ‘Shows how’ level may be assessed through a written report that is marked by a trained assessor or by observation of a piece of practice, either real or simulated, together with feedback and the trainee's reflection. Observation of real practice can also be used to assess the ‘Does’ level and this can be supported by multisource feedback. Increasing amounts of research evidence points to the critical importance to organisations of how leadership competencies are exercised (Reference Alimo-Metcalfe, Alban-Metcalfe and BradleyAlimo-Metcalfe 2008b). Therefore, we will spend more time looking at specific ways of assessing the ‘Does’ level.

Direct Observation of Non-Clinical Skills

The Direct Observation of Non-Clinical Skills (DONCS) assessment is a new workplace-based assessment tool that has been developed by the College to give feedback to advanced psychiatry trainees who are performing management and leadership tasks. Its methodology and utility is eminently useful for all grades, including consultant psychiatrists. Further information about the assessment is available at https://training.rcpsych.ac.uk/information-about-doncs-assessments.

Assessing personal qualities

A further key component of assessment must be the assessment of personal qualities, to which the MLCF refers first. Multisource feedback is a requirement for all doctors throughout their career; the individual should seek assessment from a variety of those involved with different aspects of their leadership and managerial work. It would be strongly advisable for the individual to select some (around 50%) of the assessors and trust the selection of the remainder to an appropriate and informed supervisor. The peer assessment is then placed alongside self-assessment and is analysed and fed back by an experienced supervisor. This will give valuable data on aspects of performance, as well as some measure of self-awareness. To fully explore the assessment of personal qualities, behavioural or psychological assessment of the individual doctor must be carried out. There are a number of experienced providers for such assessments of medical staff from the occupational psychology community. Such assessments will generally utilise a mixture of psychometric instruments and focused interview, the focus being on agreed key competencies associated with the individual's actual or desired role.

Lifelong learning

According to the current visions of management in medicine espoused by the GMC and the Institute for Innovation and Improvement among many, it is clear that the task of learning extends throughout a doctor's career and is not confined to time ‘in training’. The style and organisation of content is based on that of Liberating Learning (Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans 2002). The model of learning is task-based and for any doctor the most efficient and effective learning about leadership is based on the opportunities that arise close to or in their own workplace. The challenge lies in finding appropriate and practicable methods not just of supervision but also of formal coaching, mentorship and assessment. It is important that assessment is not only valid and reliable, but also educational and personal to the individual and improves on services for patients.

A successful model may operate by way of a partnership between an employing organisation and an academic body. The former gives permission and underlines the value it sees in giving its leaders the time and space in which to develop. Each psychiatrist can be actively encouraged to design, plan, implement and evaluate a service-based initiative or audit centred on their own particular clinical interest and/or role. This can be aided by a facilitator in the workplace who has knowledge and experience of the organisation. The academic body can provide expert input and support for individuals and facilitators as well as encouraging and assessing outputs, which may include reports and reflective diaries. Partnership working may become formalised, as is the case between Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust and the University of Keele, which worked together to design a programme specifically for senior medical staff working in the Trust to develop their leadership and management skills while working on real projects and initiatives related to their posts. This enabled participants to receive an academic award for successful completion, subject to university assessment (C. Vassilas, 2012, personal communication). This model of learning focused on real practice-based projects is one that is tangible for all concerned and may provide actual patient benefits.

Conclusions

The nature of medical leadership is manifold. For example, medical leadership is not simply about running teams, although that may be a part of it. Leadership is about how best to deliver services, and it includes an awareness of what lies ahead and how one can turn challenges and changes into opportunities for improving patient care. The prevailing view of leadership in public services is one of transformational rather than transactional leadership in which the important concept is of leaders influencing or pulling others – followers – to a new improved state. Leadership must, therefore, involve working with others, agreeing and setting visions that are attainable, understanding the intricacies of truly managing services and many other aspects but must always start with the ability to understand, manage and project oneself.

Leadership is not a skill for all situations: there are times to lead and times to follow and support another leader. This ability to be flexible and allow a proper distribution of leadership can only come from a mature position of insight and self-awareness and it is unsurprising that the MLCF begins with a discussion of personal qualities.

A leader must command respect, and to do this they must be knowledgeable, authoritative and have the interpersonal skills to work with the widest range of people from all backgrounds. They must project confidence and act with integrity, but be capable of humility and acknowledging when they don't know.

Whatever leadership is, and its definition remains perhaps elusive, it is vitally important. It is not innate; it can be taught, learnt and developed but it requires time, resources and expertise to nurture and maintain.

Reference Grant and SwanwickGrant (2010) points out that to be consistent with the dominant cognitive model of medical education, programmes of medical training must be guided by explicit curricula. She commended the UK General Medical Council Postgraduate Board's 2010 definition of curriculum as one that gives clarity to all stakeholders, including learners, trainers, training providers and regulatory bodies. Learning to be an effective leader, in common with other aspects of the development of a doctor such as the acquisition of clinical skills, is benefited by following a clear curriculum. The Medical Leadership Competency Framework and the associated Medical Leadership Curriculum form the basis for programmes of learning aimed at groups or individuals throughout their medical career. For psychiatrists in training, the Royal College of Psychiatrists' curricula give further clear outcomes that trainees must attain.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Successful leadership skills are:

-

a an innate personal quality

-

b irrelevant to the employing organisation

-

c easy to define

-

d a matter that can be entirely taught

-

e important for all doctors.

-

-

2 Models of leadership:

-

a are all hierarchical

-

b are unimportant when learning leadership skills

-

c are all based on military models

-

d include transformational and transactional models

-

e are specific in mental health settings.

-

-

3 The Medical Leadership Competency Framework:

-

a has five domains, each with four elements

-

b is internationally recognised

-

c is examined within the MRCPsych examination

-

d leads to a specific qualification

-

e has been developed by occupational psychologists.

-

-

4 The planning of learning:

-

a is solely a matter for a course organiser or teacher

-

b is an unconscious process

-

c involves the setting of clear objectives

-

d is unimportant in learning leadership skills

-

e concerns setting examinations.

-

-

5 Leadership skills are assessed by:

-

a written examinations only

-

b in-service or workplace-based assessments

-

c patient feedback

-

d viva examinations

-

e personality or behavioural assessments.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | d | 3 | a | 4 | c | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.