Interpersonal psychotherapy (Reference Klerman, Weissman and RounsavilleKlerman 1984, Reference Klerman and Weissman1993) is still the new kid on the block, despite an evidence base dating back to the 1970s and inclusion in multiple good practice guidelines. Training courses have been established throughout the UK and North America for over 15 years and continue to expand to an international market. National and international societies have been established to support and network practitioners, supervisors and trainers (Box 1). Yet most people would struggle to find a local practitioner in the UK and the majority of services do not routinely offer this intervention as a standard part of patient care.

BOX 1 Organisations

-

• UK Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPTUK) network: www.interpersonalpsychotherapy.org.uk

-

• International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy (ISIPT): www.interpersonalpsychotherapy.org

Origins of interpersonal psychotherapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy began in the context of research, having been developed through close examination of the literature exploring the myriad ways in which interpersonal relationships protect against, and aid resolution of, mood difficulties, and it remains closely tied to empirical evaluation. It was originally designed as a treatment for major depression. In the Boston–New Haven project, Gerald Klerman and colleagues examined the value of a socially oriented intervention, which took a pragmatic and change-oriented approach to the resolution of the interpersonal difficulties commonly associated with depressive symptoms. An initial 8-month, five-cell trial involved 150 female out-patients with depression (Reference Klerman, DiMascio and WeissmanKlerman 1974; Reference Weissman, Klerman and PaykelWeissman 1974). It compared interpersonal psychotherapy alone, amitriptyline alone, interpersonal psychotherapy plus amitriptyline, interpersonal psychotherapy plus placebo and no pill (clinical management). The trial demonstrated the superior potential for interpersonal psychotherapy plus amitriptyline to maintain an initial good response to medication, and a specific but delayed effect on social functioning for interpersonal psychotherapy.

A subsequent investigation, which involved 81 male and female out-patients with depression, moved on to the task of achieving wellness in people currently experiencing acute depressive symptoms (Reference DiMascio, Weissman and PrusoffDiMascio 1979; Reference Weissman, Klerman and PrusoffWeissman 1981). Interpersonal psychotherapy alone and amitriptyline alone showed comparable reduction in symptoms and the combined effect of the two interventions was additive. Benefits were largely sustained over a 1-year naturalistic follow-up and, once again, a specific and significant effect of interpersonal psychotherapy on social functioning was demonstrated.

The positive outcomes of these early studies supported the inclusion of interpersonal psychotherapy in the US National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (Reference Elkin, Parloff and HadleyElkin 1985). The biggest psychotherapy trial to have been conducted at the time, with 250 participants, the study directly compared interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), medication and routine care. Few differences were found between the psychotherapies, neither of which demonstrated a significantly inferior outcome to antidepressant medication as a treatment, and benefits were demonstrated to last for the majority of the 2-year follow-up (Reference Shea, Elkin and ImberShea 1992).

Sadly, the driving force behind the development of interpersonal psychotherapy, Gerald Klerman, died early in its history and it would appear that this loss had a significant effect on the propagation of the model. Researchers continued to use the intervention but the wide-spread dissemination evident in interventions of a similar generation, such as CBT, was not seen. The evidence base was, however, sufficiently developed to support the inclusion of interpersonal psychotherapy in good practice guidelines such as that published by the British Association of Pharmacology (Reference Anderson, Ferrier and BaldwinAnderson 2008). It is also to be found in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on depression in adults (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2009) and in children and adolescents (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2005) and, following a modification for bulimia nervosa by Dr Chris Fairburn, on eating disorders (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004). These now serve as a foundation for more proactive dissemination.

The therapeutic model

Interpersonal psychotherapy is a brief psychological therapy for depression. Its goals are simple and pragmatic:

-

• to reduce depressive symptoms

-

• to improve social functioning.

The benefit of working in a time-limited manner is maximised by maintaining a ‘here-and-now’ perspective on what may be recent, recurrent or even chronic mood difficulties, framing the intervention around one of four predetermined interpersonal themes (Box 2).

BOX 2 The four potential areas of focus in interpersonal psychotherapy

-

• Interpersonal role dispute

-

• Interpersonal role transition

-

• Grief

-

• Interpersonal sensitivity (formerly known as interpersonal deficits)

The process of change in interpersonal psychotherapy is presumed to be interactive: progress in symptom resolution is facilitated by progress in interpersonal resolution and vice versa. That is, if your dispute with your partner starts to resolve, you will feel less depressed and, in feeling less depressed, you will be able to work more effectively on resolving the dispute with your partner.

Interpersonal psychotherapy is integrative, in that it combines thinking most characteristic of a medical model – using explicit diagnosis, validating the difficulty of living with depression and emphasising the responsibilities arising from the role of patient – and more dynamically rooted ideas of reciprocal and repeating patterns of relationships, vulnerability arising from broken attachments, and the disadvantage to healthy living consequent to an inability to establish or maintain a meaningful and functionally diverse interpersonal network (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Interaction of mood, interpersonal difficulties and subjective loss – the basis of an interpersonal psychotherapy formulation.

The therapy follows a flexible structure, moving through three mutually informed phases of work that help to orient therapist and client to the tasks and objectives of each stage (Box 3).

BOX 3 The phases of interpersonal psychotherapy

Initial phase

-

• Close examination of current depressive symptoms and relevant history

-

• Close examination of current interpersonal relationships and difficulties

-

• Linking depressive symptoms to prominent interpersonal themes that contribute to their onset and continuation

-

• Selecting an area of focus (Box 2) that best reflects the above pattern of links

-

• Negotiating the remaining contract

Middle phase

-

• Weekly monitoring of depressive symptoms

-

• Linking depressive symptoms to current problematic examples in the focus area

-

• Working towards resolution through improved communication and recognition, and expression of associated affect

-

• Active engagement in and development of the interpersonal network to support and facilitate change required in the focus area

Ending phase

-

• Explicit discussion of ending and associated affect

-

• Review and evaluation of treatment

-

• Support for continued use of interpersonal strategies, particularly when faced with potential symptomatic relapse

The first phase constitutes assessment, giving particular attention to both the collaborative diagnosis of depression and developing an understanding of the interpersonal context. The overlap between symptomatic and interpersonal experience guides the decision on treatment focus, with four choices available: interpersonal role dispute, interpersonal role transitions, grief and interpersonal sensitivity (Box 2). The second phase takes on the negotiated focus as the guide, working to alleviate symptomatic experience through the resolution of the primary area of interpersonal difficulty. The final phase specifically addresses issues of termination of therapy.

Key tasks of assessment

Establishing the diagnosis and interpersonal activation

In interpersonal psychotherapy, a diagnosis of depression is made explicitly and collaboratively. It is common practice to use standardised measures of depressive symptoms, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ–9; Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and WilliamsSpitzer 1999), and of social functioning, such as the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (Reference Mundt, Marks and ShearMundt 2002), to provide a baseline measure of severity and range of difficulty and to serve as a means of evaluating outcome later. This is important, as it helps to establish a shared treatment target and ensure that interpersonal psychotherapy is used with the disorder for which there is an established evidence base. Clarifying the diagnosis and time line of the most recent episode of depression helps to focus attention on the issues relevant to the current episode, familiarising patients with the here-and-now approach. This also provides an early opportunity to assess, and potentially mobilise, the interpersonal resources available to the patient, which are often under-used or poorly directed, for example, ‘Who can help you with that difficulty and how?’ The therapist explains to the patient the rationale for the method and gives information about its demonstrated efficacy. This positive presentation is used to combat the despair that many patients with depression feel about their situation and to promote hope in a positive prognosis. It can also help to shape patient's views away from the self-blame characteristic of depression and towards the interpersonal context.

Relating depression to the interpersonal context

A detailed review and evaluation of the patient's relationship network is conducted early in therapy. This helps both to orient the patient to the interpersonal perspective of the therapy and to begin the prioritisation of specific areas of interpersonal difficulty for particular attention. Details are collected on the nature and function of current significant relationships and their association with the onset and maintenance of depressive symptoms. Patients are encouraged to actively evaluate current relationships and to consider how they might be contributing to the current depressive experience. This also provides an opportunity to evaluate the social resources the patient has available to facilitate work on their recovery and the extent to which these are currently being utilised.

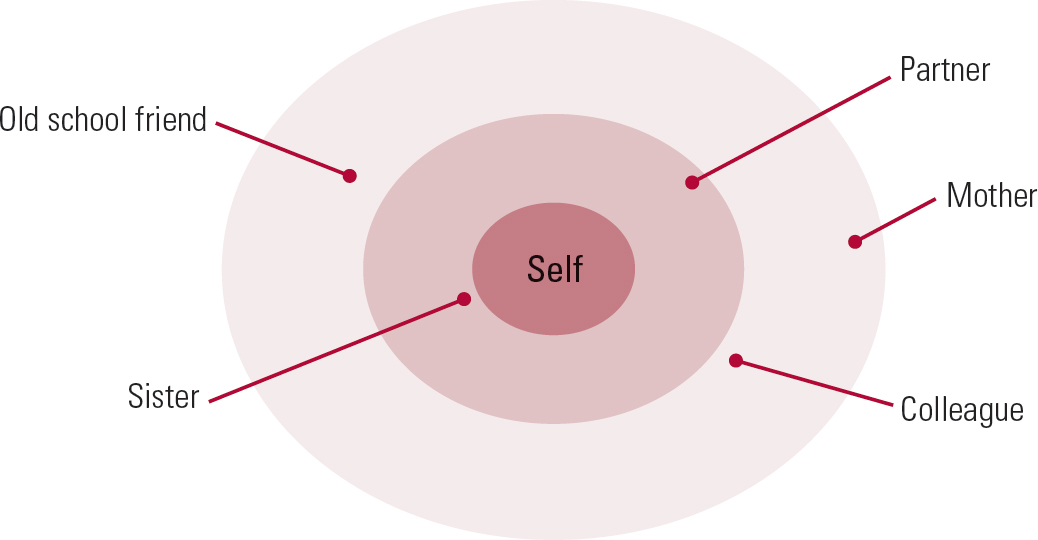

Considerable detail is collected during this stage of the assessment, and in exploring the relationships it can be helpful to create a record, such as a diagram of the patient's network (Fig. 2). This detailed inventory is a means of understanding the current interpersonal context, and clarifying current interpersonal changes, dissatisfactions and conflicts, which may guide focus selection. It is crucial, therefore, that the future task of negotiating a focus is held in mind when conducting the inventory and used to make enquiries purposeful rather than generic.

FIG 2 Inventory diagram of a patient's interpersonal network.

Identification of an interpersonal focus

Interpersonal areas are explored during the assessment phase to establish which of them reflects the primary area of interpersonal difficulty related to the current depression (Box 2). The different strands of the assessment are drawn together in a focused formulation to explicitly link the depressive symptoms to a central difficulty within the patient's interpersonal situation. This will form the basis of the second stage of treatment.

Many patients experience difficulties in more than one area simultaneously. By being helped to prioritise one area to work on, they are assisted in evaluating the relative impact of their interpersonal difficulties on their depression. They are helped to focus their limited energy on resolving difficulties in a specified area, rather than becoming overwhelmed by the enormity of tackling everything at once.

Formulation and contract setting

At its simplest, formulation in interpersonal psychotherapy reflects the selection of an interpersonal area for specific attention. The formulation is made explicit and is negotiated to be personally meaningful for the patient. The patient uses this formulation to guide their participation in the second phase of therapy and this work will be vulnerable if the focus is not collaboratively established. The interpersonal difficulties are explicitly linked to the onset and maintenance of the depressive symptoms, and resolution of these difficulties is presented as the basis for symptomatic recovery. This includes specifying treatment goals that the patient would like to work towards within the identified area of difficulty.

The four potential areas of focus

Interpersonal role transition

Many of the changes worked on within a transition focus will reflect familiar stages of personal, professional and cultural development, but in the context of depression patients are more likely to experience such changes as a loss. In some instances the loss is readily apparent, as in the end of a valued relationship or the loss of a job. In others, however, it may be more subtle, for example loss of status with retirement or loss of purpose when adult children leave home. Sometimes the change is ostensibly positive – a promotion or the birth of a child – but is still experienced as a loss – loss of peer group in a promoted post or loss of freedom with responsibility for a child.

The model identifies three interrelated phases of the intervention during which the patient is help to mourn and move away from the old role, re-evaluate the possibilities and opportunities in the transition, and clarify and master the demands of the new role to restore self-esteem. In addition, it is very helpful to clarify the context of the change and the manner in which it came about. For example, being left by your partner and leaving your partner will both involve an old role of being in a relationship and a new role of being single, but are likely to be subjectively experienced very differently. Further, as has been demonstrated in the trauma literature (Reference Kessler, Sormega and BrometKessler 1995), the involvement of another in the change coming about can be predictive of the ease of transition, for example being forced out of a job because of bullying compared with leaving a job when funding runs out.

The affect associated with each of the three phases is closely monitored to identify and target obstacles to the successful completion of the transition, for example incomplete mourning of the loss or apprehension about the demands of the new role without familiar supports.

As the intervention proceeds, increasing attention is given to the opportunities available in the new role, many of which may have been ignored or only partially considered. The patient is helped to consider all the ways in which they could create and take advantage of new opportunities or re-engage with social and practical support that was not inevitably lost with the change in role.

Interpersonal role disputes

Although relationship difficulties in the context of depression are routinely anticipated within the interpersonal psychotherapy model, the disputes focus will prioritise for more detailed attention one key problematic relationship linked to the current depressive episode. An individual relationship might become the focus because of an acute crisis or it may emerge as the focus because of another change. For example, a dissatisfying marriage may become more obviously so when one partner loses their job and tensions arise over finance. The objective is to understand the mechanisms by which the dispute is perpetuated by clarifying and resolving problematic communication patterns (Box 4) and non-reciprocated expectations.

BOX 4 Communication analysis

Used to identify, examine and rectify the patient's failures in communication so that they can learn to communicate more effectively. It includes:

-

• detailed reconstruction of content and affect

-

• noting of omissions

-

• evaluation of reciprocity

-

• noting of links to depressive symptoms

-

• highlighting of opportunities for clarification and revision of communication style

Disputes work focuses on detailed reconstructions of unsatisfactory exchanges, reviewing not only what was said but how it was said, how it was received, what was left unsaid and to what extent the communication achieved the desired outcome. Patients seldom provide this level of detail spontaneously and must learn to do so through repeated practice. Once the issues, non-reciprocated expectations and mechanisms of the dispute are clarified, the options for change, through improved communication and use of interpersonal resources, are explored by practising more direct and empathic approaches.

Although interpersonal psychotherapy is typically delivered as an individual therapy, the other party in a dispute is often invited to a session early in treatment, to engage them in the work and foster a shared goal of resolution. There is also scope within the disputes focus to review the ways in which the primary dispute is repeated in other relationships, as might be the case if the patient has poor skills in a specific area, such as unassertive communication or avoiding talking about feelings. This review is helpful in clarifying the extent of the difficulty and providing opportunities to practise alternatives that might contribute to the resolution of the primary dispute.

Grief

The grief focus is selected if depression following a bereavement creates an obstacle to mourning or to sustaining or developing relationships in the remaining network. The goal is to illustrate to the patient that their experience is not simply the natural consequence of their loss, but is indicative of a mood disorder. The pattern of their depressive symptoms is traced back and guides therapist and patient in understanding how the depression interferes with functioning in current relationships.

Interpersonal psychotherapy encourages the patient to describe the relationship they had with the deceased, starting with the preoccupying memories and working towards a balanced review of the whole relationship. The patient is supported in discussing warded-off memories, perhaps related to intolerable feelings or periods of conflict, which characterise many relationships. As with the other focus areas, close attention is maintained on the expression of associated affect (Box 5).

BOX 5 Working with affect in interpersonal psychotherapy

-

• Facilitate the patient's implicit acknowledgement and acceptance of affect

-

• Support the patient's explicit use of affect in communication and in bringing about interpersonal changes

-

• Encourage the pursuit of desirable affect

Particular attention is given to the period surrounding the death and the ways in which this might have interfered with mourning, for example following a suicide or traumatic death, and also to how social support was used at the time and how it can be engaged now. This offers a further opportunity to consider and promote the support that is currently available, and the interpersonal opportunities that remain open to the patient or that could be developed.

Attention to the remaining interpersonal network is sustained throughout this work, encouraging opportunities to re-engage or develop relationships that could meet current and ongoing needs. Care is taken to avoid the therapeutic relationship becoming a replacement for the lost relationship, through actively supporting the patient's use and exploration of the relationships that remain available to them.

Interpersonal sensitivity

Patients for whom interpersonal sensitivity/deficits is the primary focus often have a history of interpersonal relationship difficulties or isolation extending far beyond the period of the most recent episode of depression. This distinguishes them from many other patients, as they may not have experienced a prolonged period of higher interpersonal functioning before the onset of depressive symptoms to which they wish to return. Given the more pervasive nature of the interpersonal difficulties these patients experience, it is important to tailor the expectations of therapy accordingly.

Given the often long-standing nature of the difficulties, the goals of this area are modest and aim to establish a greater sense of connection with other people. The balance between deepening the connection in existing relationships and establishing new contacts will vary depending on the initial presentation, but there will be an emphasis on making the most of whatever limited resources are presented. This will often involve the patient taking hitherto avoided risks.

The range of relationships used in the middle sessions differs for patients with interpersonal sensitivity, as here-and-now relationships are probably scarce. As a consequence, previous relationships are also reconstructed to understand how they worked, any successes that were achieved and also the ways in which those relationships became vulnerable and faltered.

One of the distinct aspects of work in this focus area is the direct attention given to the therapeutic relationship, which is rare in the other focus areas. In interpersonal sensitivity, the therapy relationship may be the best illustration, if not the only current information available, on the difficulties the patient encounters in interpersonal contacts. This provides an opportunity to work collaboratively in understanding the difficulties that emerge, providing constructive feedback to the patient which is unlikely to be available otherwise. It also creates numerous opportunities for the therapist to model alternative ways of dealing with the problems the patient repeatedly faces in relationships, often leading to their poor quality or termination.

Issues of termination

As therapy concludes, increasing attention is given to the end of the therapy relationship and to relapse prevention. It is important to provide information to help the patient normalise their response to ending and distinguish an appropriate emotional response from a depressive one.

The course and progress of therapy are reviewed in detail, with clear attention given to the competencies developed and the way in which these were facilitated by improved interpersonal engagement within and outside of therapy. Comparative measures of depressive symptoms and social functioning are used to focus this discussion. The review can also be assisted by revisiting the interpersonal objectives discussed at the start of treatment and the progress that has been achieved.

The therapeutic relationship

The therapeutic relationship is of crucial importance in interpersonal psychotherapy, but is rarely an explicit focus of discussion. The aim is to foster a positive transference as the basis for a collaborative relationship. This is used as a valuable source of information and a basis for modelling an adaptive interpersonal style. However, the transference is not an explicit focus and interpretation is rarely used. Rather, the therapeutic relationship is used to support and encourage focus on relationships beyond the therapy room. The interpersonal sensitivity focus is the main exception to this position because of the assumed paucity of external relationships – defined either by number or quality. In these cases, the interpersonal patterns enacted in the therapy relationship are observed and reviewed to aid understanding of the process. Even here, however, they are used not as an exclusive focus but as a pragmatic tool through which external relationships or opportunities might be better understood and utilised.

The evidence base

The literature on interpersonal psychotherapy initially focused on major depression in adults (Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and AnderssonCuijpers 2008), but it has expanded across the age range, with randomised controlled trials involving adults of working age (Reference Elkin, Parloff and HadleyElkin 1985), adolescents (Reference Klomek and MufsonKlomek 2006) and older adults (Reference Post, Miller and SchulbergPost 2008). The type of depressive disorder has also been explored, with treatment for acute episodes (Reference Luty, Carter and McKenzieLuty 2007), recurrent depression (Reference Frank, Kupfer and BuysseFrank 2007), chronic depression (Reference Blanco, Lipsitz and CaligorBlanco 2001; Reference MarkowitzMarkowitz 2003; Reference Schramm, Schneider and ZobelSchramm 2008), dysthymia (Reference Browne, Steiner and RobertsBrowne 2002; Reference Markowitz, Kocsis and FishmanMarkowitz 2008) and bipolar disorder (Reference Frank, Kupfer and ThaseFrank 2005) all having come under scrutiny. The context in which depressive symptoms are experienced has also drawn attention, particularly medical contexts such as the peri- and postnatal period (Reference Grote, Swartz and GeibelGrote 2009), post-stroke (Reference Finkenzeller, Zobel and RietzFinkenzeller 2009), post-myocardial infarction (Reference Lesperance, Frasure-Smith and KoszyckiLesperance 2007), in patients with cancer and their partners (Reference Donnelly, Kornblith and FleishmanDonnelly 2000) and in HIV-positive patients (Reference Markowitz, Kocsis and FishmanMarkowitz 1998; Reference Ransom, Heckman and AndersonRansom 2008).

The literature is also no longer limited to the treatment of depressive disorders. It addresses interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders (Reference Fairburn, Jones and PevelerFairburn 1991, Reference Fairburn, Jones and Peveler1993) and for anxiety disorders, including social phobia (Reference Hoffart, Borge and SextonHoffart 2009), panic disorder (Reference Lipsitz, Gur and MillerLipsitz 2006) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Reference Bleiberg and MarkowitzBleiberg 2005; Reference Robertson, Rushton and BatrimRobertson 2007; Reference Krupnick, Green and StocktonKrupnick 2008). After depressive disorders, the evidence base for interpersonal psychotherapy is the most developed for eating disorders, and the intervention is recommended in NICE guidelines for eating disorders (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004). Although most of the literature examines interpersonal psychotherapy as an individual intervention, it is by no means limited to that. A number of publications examine interpersonal psychotherapy delivered in a group format (Reference Bolton, Bass and NeugebauerBolton 2003; Reference Verdeli, Clougherty and OnyangoVerdeli 2008), across different cultural settings (Reference Bass, Neugebauer and CloughertyBass 2006; Reference Rossello, Bernal and Rivera-MedinaRossello 2008), delivered by telephone for patients who cannot easily attend sessions (Reference Miller and WeissmanMiller 2002; Reference Ransom, Heckman and AndersonRansom 2008) and as a therapy for couples in disputes (Reference Klerman and WeissmanKlerman 1993).

Limitations and contraindications

The pragmatism and focus on change in interpersonal psychotherapy are often welcomed by therapists and patients alike. However, the lack of a coherent theoretical statement underpinning the model can be a cause of concern for practitioners, especially when clinical difficulties arise and guidance is sought to resolve the challenges characteristic of psychotherapy. The simplicity of the model makes it highly accessible but can obscure the sophistication of the work demanded in the relational domain. It is in this area that the simple categorical approach can offer inadequate guidance. This is in part addressed by requiring that therapists undertaking training in interpersonal psychotherapy already have a formal mental health qualification and experience in conducting psychotherapy. Nevertheless, training is often a complex and unsatisfactory process of simultaneous translation as new therapists attempt to formulate from a variety of default theoretical perspectives while seeking to practise in manner adherent to the interpersonal psychotherapy model.

The literature on interpersonal psychotherapy is not devoid of theoretical discussion, with attachment theory, communication theory and social theory being offered individually and in combination to capture the theoretical driving forces (Reference Stuart and RobertsonStuart 2003). Nevertheless, there remains scope for a more coherent and dynamic theoretical frame of reference.

In addition, there is limited understanding of the specific mechanism of change and active ingredients of the interpersonal psychotherapy model. Furthermore, the tendency for modifications to offer only minor deviations from the original framework has done little to elucidate the necessary and optional components in the practice of the therapy. For example, many researchers have examined the impact of changing the duration of the intervention from the standard 16 sessions to 12 and 8, finding no discernible negative effect on outcome, but few researchers have explored interpersonal psychotherapy as an open-ended rather than time-limited intervention (Reference BatemanBateman 2009).

The necessity for a medically defined diagnosis and sick role, rather than a more psychologically oriented formulation of the depressive experience, is often a matter of heated debate on interpersonal psychotherapy training courses, but has not been taken up for empirical evaluation. Consequently, the literature substantiating the validity of interpersonal psychotherapy as an intervention outweighs that which examines and explains how it works.

The fourth focus area, interpersonal sensitivity, is widely recognised to be poorly developed in comparison with the other three areas, and authors often advise against using this area if possible (e.g. Reference Weissman, Karkowitz and KlermanWeissman 2000). In contrast, therapists new to interpersonal psychotherapy often struggle to identify any other focus areas when initially confronted with illustrative case material during training. Although this can, to some extent, be explained by lack of familiarity with the process and goals of the focuses, the struggle to grasp the thorny issue of chronic interpersonal difficulties is at times evident and has resulted in a limited body of evidence in relation to this subgroup. It is undeniably true that it can be a much greater challenge to work in a relational manner with individuals who have few or no relationships, but avoiding this work is not an option for many practitioners and the relatively few empirical or discursive papers examining the process and prognosis for work in each of the focus areas offer scant assistance.

Although interpersonal psychotherapy has shown promise in many clinical areas, it makes no claims to be a panacea. To date, there has been no clear evidence of benefit in using interpersonal psychotherapy in the field of substance misuse (Reference Carroll, Rounsaville and GawinCarroll 1991, Reference Carroll, Rounsaville and Gordon1994; Reference Markowitz, Kocsis and ChristosMarkowitz 2008). Neither have its cost-effectiveness in treating populations with chronic difficulties such as dysthymia (Reference Browne, Steiner and RobertsBrowne 2002) and the extrapolation from bulimia nervosa to anorexia nervosa (Reference McIntosh, Bulik and McKenzieMcIntosh 2000) been matched by clinical benefits for patients. Work with anxiety disorders such as PTSD, social phobia and panic shows more promise, but remains at a preliminary stage, preventing any firm conclusions on the wider application of this model.

Expanding provision in the UK

Various local and national initiatives have sought to revise the slow dissemination of the interpersonal psychotherapy model in the UK. The Doing Well by People with Depression project, which was set up in 2003, took interpersonal psychotherapy to nine regions in Scotland, with a view to sustainable practice, and it has served as the basis for establishing a national network and specific posts for interpersonal psychotherapists (Reference Sloan, Hobson and LeightonSloan 2009).

The National Health Service (NHS) in England is in the midst of a similar breakthrough. With the formidable force of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, it has seen an unprecedented investment in psychological therapy for depression and anxiety. The criticisms raised when initial funding was invested only in CBT were addressed by the then Secretary of State for Health Alan Reference JohnsonJohnson (2008). In a Statement of Intent, Mr Johnson made patient choice a priority for the evolving IAPT services. Consequently, interpersonal psychotherapy, along with the other evidence-based therapies for depression and anxiety, is now to be provided in primary care services on a national scale. If successful, this initiative will more than triple the number of interpersonal psychotherapy practitioners and supervisors in England and will result in a move towards a greater equity of access and provision across the country, contributing to increased patient choice (details available from the author). To support this expansion, an expert group has been formed to develop a statement of competencies for interpersonal psychotherapy. This document will serve as the basis for a national curriculum underpinning practitioner and supervisor training, ensuring close governance of the expanding population.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Interpersonal psychotherapy was originally developed as a treatment for:

-

a eating disorders

-

b marital disputes

-

c social phobia

-

d major depression

-

e interpersonal distress.

-

-

2 Interpersonal psychotherapy involves assessment of:

-

a current interpersonal relationships

-

b dreams

-

c the unconscious

-

d the mother–child relationship

-

e cognitive style.

-

-

3 The focus areas in interpersonal psychotherapy are:

-

a thinking errors and cognitive bias

-

b interpersonal transitions, disputes, grief and sensitivity

-

c unconscious wishes

-

d reciprocal role procedures

-

e subjective units of distress.

-

-

4 The structure of interpersonal psychotherapy:

-

a follows three mutually informed phases

-

b is determined by the patient

-

c is determined by the therapist

-

d is guided by free association

-

e is negotiated independently at the start of each session.

-

-

5 Key interventions in interpersonal psychotherapy include:

-

a thought diaries

-

b assertiveness training

-

c social skills training

-

d expression of affect and improved communication

-

e relaxation training.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | a | 3 | b | 4 | a | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.