In Part 1 of this overview (Reference Mace and BinyonMace & Binyon, 2005) we described psychodynamic formulation in terms of four levels of attainment:

-

1 recognising the psychological dimension;

-

2 constructing an illness narrative;

-

3 modelling a formulation;

-

4 naming the elements.

Here we concentrate on educational requirements at each level and teaching methods that are appropriate to develop skills in formulation. Although we focus primarily on the needs of psychiatrists in basic and higher training, we believe formulation skills to be useful for all doctors. Preparation should therefore begin during undergraduate teaching.

Reading the person in the patient

Many changes are occurring in the practice of medicine for the 21st century, one of the more positive being the emphasis on treating patients in a holistic way and involving them in their treatment planning. Most doctors agree with this aim, but in practice it can be a daunting prospect, adding a new dimension to the skills required of a practitioner. At its root is the need to be able to understand patients’ reactions to their circumstances. Although a consultation with a doctor may seem commonplace to us, for a patient it is often associated with fear, pain and anxiety. Little wonder, then, that they do not always respond in what we consider a ‘rational’ way.

Most modern medical school curricula place emphasis on seeing the patient as a whole person existing in their own social and psychological environment rather than as a specimen under a microscope. This is a widely accepted educational philosophy (e.g. General Medical Council, 2003), but not always evident in practice. Beyond familiar-isation with mental disorders, psychiatric education has a lot to offer in encouraging students to consider psychological aspects of their patients’ problems. Knowledge of the basic level of psychodynamic formulation can be extremely helpful in recognising the personal in medicine.

Within clinical psychiatry, the needs of people referred to consultant teams are rarely simple. If a diagnosis of depressive illness and the judicious use of support and medication were enough, then, given the sophistication of most primary care services, this is likely to have been provided already. Anybody referred to mental health services will need careful appraisal of their needs and psychological and social functioning that takes account of their outlook and likely responses and resistances to treatment.

Using the need to know

Teaching of psychodynamic formulation should be an integral part of the teaching of psychiatric assessment. At each level, it will be important to motivate the student group and to engage their willingness to learn. This is often best done by relating formulation to clinical predicaments that are challenging the students at the time. It may involve using dynamic concepts to shed light on an unexpected reaction, as in David Reference MalanMalan's (1979) discussion of why a young child may turn away from her parents when they visit her for the first time in hospital. Alternative material that is useful here is George Reference VaillantVaillant's (1992) examination of why an infertile woman who has undergone a hysterectomy may write letters of complaint (or behave in other unexpected ways) after the operation. Material derived from general hospital practice or primary care can be very persuasive with undergraduates whose fears of psychiatry otherwise prompt them to split the experience off from the rest of their clinical education.

With trainee psychiatrists, appreciating the uses of formulation discussed in Part 1 of this overview can assist motivation to learn the process. Why won't Mrs W talk to me? Why did Mr X shout at the specialist registrar during the ward meeting? With senior trainees, questions about what action to take will become more prominent. How will Ms Y react to being in a group at the day centre? What is the most useful thing for the ward team to understand about Mr Z so that he cuts himself less? For experienced psychiatrists who have long-term relationships with patients, yet other questions arise. Why do I feel utterly helpless after 5 minutes with Mr A? How could I have been taken in by that? Why is there never any time left to discuss Miss C? Finally, the psychiatrist providing ongoing psychodynamic treatment needs tools that help to map the tasks within the therapy. What kinds of new experience are likely to be anxiety-provoking, but potentially liberating, for this person? Are there ways of approaching this person that are likely to reduce resistance rather than arousing it?

Whatever the students’ level, there is no better motivator for learning more about formulation than connecting with an existing need to know. A few minutes spent discovering some of the dilemmas currently faced by students can pay dividends. This should not provide a licence to turn a teaching session into a surgery or confessional, but, in addition to engaging interest, it will help the skilful teacher to select exemplary material that relates to some of the interests of those in the room.

As in other situations where the primary aim is to develop clinical skills, we believe a small-group format to be optimal. Athough it is possible to provide material on general principles in a more didactic setting, such as a course lecture for the College's membership examinations, the teaching of formulation requires students to be free to prepare ideas through small-group discussion and to interact with the teaching clinician in a situation that allows everybody to contribute several suggestions. This is likely to mean a maximum of eight students for a 1 h session.

Principles of teaching

Although the content and sophistication of teaching will vary at each level of attainment, the basic educational principles for teaching psychodynamic formulation are the same. These are outlined in Table 1. First, existing knowledge is activated through an exploratory discussion, interspersed with reminders and prompts about the nature of formulation. Active questioning around themes outlined in Part 1 (the difference between formulation and diagnosis; the aims of formulation) can be helpful, as can a group attempt to formulate some pre-prepared material. Doing this permits a quick diagnosis of the group's needs in terms of the four levels of attainment listed in our opening paragraph. (These should never be assumed from the professional standing of the students.)

Table 1 Cycle of teaching

| Setting | Task |

|---|---|

| Small-group seminar | Activate previous knowledge |

| Small-group seminar | Add theory |

| Clinical experience | Practise the application |

| Supervision | Consolidate |

In rough terms, work at level 1 (recognising the psychological dimension) is required if it is apparent that the students fail to appreciate patients as people with feelings who understandably react in all kinds of ways. Level 2 (constructing an illness narrative) would be mastered during early experiences of psychiatry (including working in foundation year posts). Level 3 (modelling a formulation) represents the goal for the early years of psychiatric training. Level 4 (naming the elements) is essential for higher training in psychotherapy, but is certainly desirable for specialists in other branches of psychiatry in the later stages of training.

Level 1

The aim at this level is to ensure that students achieve a basic psychological mindedness. At any level, dynamic explanation is possible only if the student tries to enter into the patient's experience and to see apparently pathological or even bad behaviour as an adaptation to unmanageable feelings. Level 1 teaching should therefore help the student to enter the patient's feelings and understand their motivations. It will not lead to a cogent formulation, but prepares for the later stages of formulation training and helps to prevent irretrievable breakdown in relations with patients owing to intolerance and misunderstanding.

Method

How this is achieved may need to be tailored with sensitivity and flexibility to the individual student. Rather than interrogate an already confused and insecure student, one strategy might be to discuss some case histories to illustrate the difference between a purely diagnostic and a subjective understanding of a presentation.

The case histories chosen should be relatively straightforward in diagnostic terms. They should also include strong indications from the descriptions of the patient's behaviour and choice of words of how he or she was feeling, and sufficient information from the history to suggest several reasons for why a particular feeling was present.

Discussion should centre on the patient's likely feelings, why they might have been experiencing these and why they might have taken apparently irrational actions. As the students begin to realise that a patient's speech and actions are intelligible in the context of that person's subjective experience, the teacher should prompt and nurture their curiosity about others’ feelings and motivation.

Level 2

The objective at level 2 is to develop an appreciation of the continuity between an individual's inner life and their behaviour when ill, including their attitudes and response to treatment. Level 2 teaching helps students to develop confidence in constructing a narrative account of a patient's difficulties that is informed by their subjective experience. Successful assimilation can also be expected to bring benefits when motivating patients to undertake or persist with treatment and in other key communications.

Method

It is important that some didactic teaching has already been provided on psychological factors in illness. To develop the students’ clinical skills at this level, it is useful to demonstrate a generic method of assessing personal background alongside psychological function. It is neither important nor necessarily helpful to use a particular psychodynamic theory at this stage. The emphasis should be on good history-taking to tease out key influences during the patient's development and their ways of coping, whether or not these are seen as adaptive. This requires cultivation of the capacity to use interviews to empathise with and understand the patient, rather than simply to obtain information.

Teaching can begin by encouraging students to imagine the subjective experience of past patients. This helps them to practise empathic techniques that allow them to move between the patient's subjective experience and their own objective analysis of the patient's position. The main purpose is to ensure that students recognise how psychological factors may influence presentation of disease and use this recognition in their narrative account of the patient's illness. These factors will include the reactions of others (including the student) to the patient, which will probably be incorporated in material that is discussed.

However, the real challenge at level 2 is to reinforce this teaching through apprentice-style learning on individual patients as the student encounters them. This is likely to be heavily dependent on the enthusiasm or otherwise of consultant educators.

It is desirable that learning derived from each new patient history be shared with a number of students. An excellent forum for such sharing is a weekly case discussion group in which students present cases reports to a psychologically minded teacher who can then assist in drawing out relevant factors.

Case vignette: Alice

A 25-year-old woman, Alice, presented to her general practitioner (GP) with some symptoms of depression: low mood, anhedonia, comfort eating, difficulty sleeping and thoughts of self-harm that on several occasions became overwhelming and led to drug overdoses. She had taken two overdoses in the past month that turned out to have been larger than she admitted at the time. A diagnosis of depression was made and an antidepressant started. She failed to respond and the GP referred her to an out-patient psychiatric clinic for assessment.

It is found that Alice has felt ‘depressed’ to a greater or lesser degree for as long as she can remember. Despite this, she has managed to cope in the past and gained ‘A’ levels before joining a managerial training programme for a well-known retailer. Things have worsened recently following the break-up of a 2-year relationship with a man. She is finding it difficult to come to terms with this, despite support from a number of friends. Further questioning reveals that her father died when she was 5 years old. She has vivid memories of him and missed him terribly at the time. She is the middle of three children, and the only girl. Since childhood she had felt that her mother always favoured the boys and had found it difficult to be close to her. Her mother had experienced episodes of depression and Alice thinks she was in hospital for a while after her father's death. She has a recollection of being cared for by an aunt for several weeks.

In his referral letter, the (50-year-old male) GP communicates a great sense of urgency. He also rings up several times to speak personally to the assessing doctor to convey his concern and to seek feedback. The assessing doctor and the student (both younger females) did not pick up any of the same sense of desperation when they saw Alice. To them, she had seemed very much in control, almost cold.

At this level it would be necessary to explore with the students on an almost intuitive basis two questions.

First, why was Alice presenting in this state now, rather than at any other time? The discussion is likely to look first at recent precipitants, such as the coincidence of her depression with the ending of the relationship with the boyfriend. Further exploration might consider the nature of this relationship. How was he viewed by her? What kind of expectations were evident? Are these characteristic of most relationships of people at that stage of life, or is there any sense that they were influenced by earlier events? In this way, participants in the discussion might make links between the pain of losing a first boyfriend on whom she had allowed herself to become exclusively dependent – for guidance as well as emotional support – and the pain she felt on suddenly losing a father who was everything to her.

Second, why were the reactions of the GP so different from those of the assessing doctor? It is likely that Alice behaved differently in the two consultations. Discussion of what is known about this can lead to an assessment of the ways in which her reactions to men and women differ when she feels in need of support from them. This in turn may prompt questions about her past experiences. From what is already known, Alice's father's responsiveness and their special friendship contrasts with her sense that her mother was not interested and would desert her in her hour of need. This point is important in understanding Alice's needs and responses, and the discussion might consider the implications for future management of her illness. How might she be expected to behave towards different helpers? What emotions might she arouse in those trying to help her? Could these lead them to act in ways that would not actually be helpful? For example, a helper drawn into identifying with Alice's mother might be dismissive and rejecting, whereas one who identifies with her father might become very anxious and solicitous.

Through a careful attempt to understand Alice's feelings and reactions, during which the students’ empathy, curiosity and imagination are engaged, an account of her presentation and current problem emerges that links formative experiences, such as losses and parental illness in her childhood, with her characteristic ways of coping as an adult.

Level 3

The objective at this level is to produce a structured account that not only makes sense of the patient's predicament, but informs the planning of treatment and predicts some likely responses to it. Senior house officers (SHOs) will be used to summary case formulation in terms of predisposing, precipitating and maintaining factors. Psychodynamic aspects can usefully be structured in a similar way (see Part 1 of this overview). Senior house officers will also have an outline knowledge of some of the theories that underpin psychological therapies, although neither breadth nor depth of knowledge can be assumed. Once the predisposing, precipitating and maintaining factors have been set out, we recommend that available theoretical knowledge be harnessed in summarising apparently contradictory aspects of the patient's responses in terms of one or more underlying conflicts.

Methods

Background teaching is now likely to include familiarisation with the way in which psychodynamic thinkers have conceptualised the unconscious mind and human motivation. It should include the contrasts between models based on theories of instinctual drives and object relations. This will provide trainees with a greater range of ways in which to understand and discuss conflict, even if the theories and concepts invoked are incompletely assimilated.

We have found that it is important to keep SHOs’ understanding continuously grounded in real situations. Even the teaching of psychodynamic theory should not lead them away from what they are learning intuitively through experience. On a day-to-day level, they need to be encouraged to look for and think about the psychological aspects of all the cases they encounter. All SHOs should now be attending a group in which this is encouraged. This may be a dedicated case-discussion group, as recommended for first-year trainees in successive College guidelines for training in psychotherapy (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2002), or a psychotherapy supervision group in which the trainee is an observer (being as yet unready to have personal responsibility for cases).

In such group meetings trainees can develop their practical skills at formulation by re-engaging previous learning concerning the value of the narrative perspective and its practical importance in understanding clinical interactions. We therefore encourage SHOs to bring to these sessions cases that have disturbed them in some way. Often, a reflective exploration of a patient's psychopathology and functioning enables trainees to understand in a way that is immediately helpful why they are being affected by that patient. To build on this, trainees should aim to structure their observations in order to arrive at a more cogent formulation in which the contributing factors are critically evaluated and a compact summary of underlying conflicts is stated.

As an example let us consider an SHO who has a personal relationship with Alice, whom we introduced above.

An SHO, Colin, reports to a discussion group that he is aware of a strong need from a new patient for things to be made better for her. He has enquired more about the pattern of her adult relationships and discovered that her ex-partner Barry was some 15 years older than her. In this relationship, she had been very dependent, preferring all decisions to be taken by Barry and tolerating sexual relations in order to feel loved. Even after he left her, she voices disappointment rather than criticism of him. There appeared to be a sharp contrast here with her persona at work, where Alice described herself as a high-flyer on her management training scheme. It also emerges that her father's sudden death was the result of a car crash, just after what Alice remembers as an enormous row between her father and her mother. She recollects how her mother shouted that she never wanted to see her father again. Alice admits she has blamed her mother for her father's death, although she has never said so openly, and she feels very unsettled whenever she senses anger around her.

We begin to see a complex picture emerging that will help in understanding Alice's contradictory functioning, as well as her ability to compart-mentalise her life and to be very different in different circumstances.

To understand why she is reacting to the SHO as she is requires a systematic attempt to distinguish between predisposing, precipitating and maintaining dynamic factors. Theoretical ideas should be introduced as appropriate, letting them be taught through illustration during the discussion. Concepts such as transference and countertransference can illuminate discussion of the interaction, and theories of personality and psychosexual development might be introduced in going beyond what is immediately reported to discuss conflicts that underpin Alice's experience and actions.

Group discussion of the situation presented by Colin encourages participants to discriminate between psychodynamic factors that have predisposed to Alice's presentation and those that have precipitated and maintained it.

During the discussion, the precipitation of her recent depression is linked to loss of the relationship with Barry. The exclusivity of this relationship and her passivity within it, as well as its resonance with the traumatic death of her father in childhood, are commented on. In looking at other aspects of her predisposition to depression, its recurrence is examined. Previous episodes are found to have coincided with times in her life when crucial supports have been removed, for example when friends moved away. When she was aware that she was becoming sad she struggled to cope, but quickly became filled with pessimism and despair. The group links this with her experience of having a mother whose depression left her unable to cope and who was unavailable to help her find the resources to accept and assimilate her own feelings, rather than remaining terrified of them. These, of course, include aggressive feelings, which it was impossible for Alice to express towards either of her parents and which she now habitually buries.

The discussion switches to Alice's defences and how these not only predispose to, but maintain, her depression. Her fear of facing the pain of loss and her pattern of turning aggressive feelings against herself number among internal maintaining factors that are identified.

Finally, the group discusses external maintaining factors. It is noted that Alice's tendency to be extremely passive in close relationships (and to have these relationships end when her partners fail to cope with her expectations for unquestioning but unreciprocated care) reinforces her internal psychological situation.

Encouraged to think about the nature of underlying conflicts, the trainees comment on the split between a very autonomous self that strives for success and independence from others and a needy self that is felt by Alice (and by them) to be insatiable. There seems to be a primary conflict for Alice over the autonomy she can maintain in relation to others. There are other kinds of psychodynamic conflict evident here too. Her inability to move beyond very dependent relationships with men whom she idealises to a sexually mature partnership is apparent from the pattern of her relationships. She also experiences internal conflict over the experience and expression of aggressive feelings.

The primary teaching emphasis here is on recognising conflict and its effects. Different terms (such as the false self, depressive anxiety and the Oedipus complex) can be introduced in discussion, according to the trainees’ readiness.

The dynamic understanding that has now been reached facilitates predictions regarding practical clinical questions. As discussed in Part 1, these will include the part psychotherapy could play in the management of Alice's illness, the form it might take and her likely responses to it. The formulation that has been modelled here suggests that Alice's coping self might resist invitations to enter therapy, and that once a relationship with a therapist is underway there is a risk that she will become passively dependent and very demanding. This should influence both the selection of the therapist and the supervision of the subsequent work. In practice, the implications extend well beyond this, however.

Alice does not attend her first appointment for psychotherapy assessment, but forms an attachment to a male community psychiatric nurse, Dennis, in the community mental health team. She tells him that she feels he is more helpful than anybody else and he agrees to see her regularly. Initially flattered, Dennis subsequently becomes alarmed when Alice starts telephoning him when he is on call, demanding additional meetings. He brings this back to his team meeting.

There is now a collective need for Alice's behaviour to be understood and for Dennis to extricate himself in a way that does not further traumatise her. An ability to formulate Alice's needs psychodynamically might help the team to understand how this difficult situation with a patient has developed and to respond to it. However, prerequisite to a psychodynamic formulation is the team's ability to see their own responses in psychodynamic terms and to understand the importance of boundaries, the pull of ‘special’ patients and the power individual team members always have to sabotage others’ work in the treatment programme.

Level 4

At level 4 the aim is to construct a comprehensive case formulation that not only can inform care planning, but that explains the nature and severity of the patient's difficulties in terms that will be widely understood. The operationalised psychodynamic diagnostics (OPD) system (OPD Task Force, 2001) that we introduced in Part 1 provides a useful and very teachable method for this.

By this stage it is hoped that the trainees will have developed the fairly sophisticated skills necessary for detailed formulation. These include a capacity to undertake full psychodynamic enquiry during one or more assessment interviews, and to identify and flexibly pursue necessary lines of investigation. As a result, judgements about the patient's experience and personality can be attempted that are supported by clear historical evidence. Throughout an interview trainees must also be able to monitor and recall their own experiences, as these may help them to identify patterns of interaction and hidden affects in the patient.

Such interview skills are accompanied by a more developed understanding of psychodynamic theory, so that a patient's enduring traits, patterns of interaction and experienced conflicts can not only be labelled appropriately, but appraised in terms of their severity. This will require extended teaching on the principal psychodynamic models of the personality, supported by their regular application to clinical situations in seminars led by experienced psychotherapists.

Method

The OPD system is especially well suited to group learning because it involves several distinct operations, each requiring the recording of observations and judgements. These operations can be isolated and given selective attention according to students’ needs. Group discussion and rating of examples, with constant reference to definitions and illustrations in the OPD manual (OPD Task Force, 2001), facilitates mastery of the various procedural rules. Psychodynamic formulations are produced once clinical observations have been translated into separate statements concerning structure, interpersonal relations and conflict. Refinement of each of these requires slightly different group-learning experiences.

Interpersonal relations

It can be helpful to consider interpersonal relations first, as this makes full use of personal observations and trainees’ own feelings. The process involves identifying the most characteristic experiences for the patient or for others from descriptive information and countertransference (see Part 1: Box 5). Discussion should first refine a shortlist of the most characteristic forms these interactions take (regularly referring to clinical observations). Each trainee should record their first thoughts using a copy of a structured checklist (OPD Task Force, 2001) before the seminar leader attempts to draw up a consensual version restricted to two or three types of interaction in each category. The group then considers how these interrelate to produce an interpersonal formulation in the shape of a sequence of interactions.

Structure

Consideration of structure entails assessment of the level of integration a patient shows with respect to the six aspects it encompasses (see Part 1: Box 4). Detailed keys assist in the making of such judgements, which demand constant referral back to knowledge of the overall pattern of a patient's affects, defences, relations with others and management of themselves. In group discussion, familiar information is reassimilated and used in attempts to reach consensus on each of these judgements.

Conflict

The final OPD dimension to discuss is conflicts within the patient (see Part 1: Box 6). The group should consider not only which kinds of conflict are present, from their understanding of the patient's inner world, but also select those that have been most disabling, from their knowledge of the patient's functioning.

Relating OPD to the example of Alice

In the case of Alice, a good deal of material is already available from of her history and mental health professionals’ experiences of being with her. (As with level 3 formulation, it is not essential to have conducted a formal assessment for psychotherapy in order to produce a cogent formulation. It is essential, however, to have accounts of how professionals have felt while talking to the patient.) This material is sufficient to attempt a first formulation using the OPD system, with the proviso that revision may be necessary as more information becomes available.

Interpersonal relations

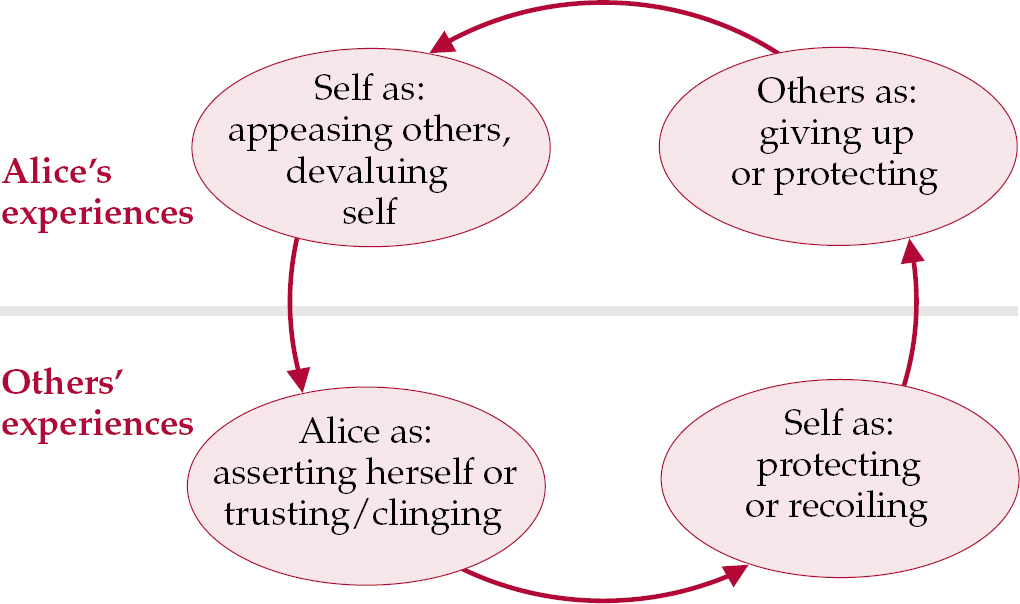

In terms of her interactions, Alice tends to see others as either ignoring of her or unreliable, and she feels that she gives into others while blaming herself. Others’ experience of her, however, is that she is either assertive or clinging, while they find themselves feeling very protective or wanting to cut off from her. These cyclical interrelations are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Summary of interpersonal relations.

The formulation of cyclical interpersonal patterns in this way can be of considerable practical help in psychiatric management and they should be discussed during teaching. For instance, this formulation might have helped Colin to anticipate the pull to be overprotective towards Alice and to establish clear boundaries in his work with her that did not collude with her expectation that he would either take care of everything or reject her.

By clarifying areas in which intentions are likely to be misunderstood and the ways a given patient is most likely to apply pressure on staff to act out of role, formulations can also help staff teams to maintain consistent and therapeutic boundaries in their work.

Structure

Reflection on the six structural dimensions (Part 1: Box 4) shows considerable consistency in the lack of integration that is evident within Alice. Self-perception is compromised by inconsistent identity; self-regulation fails at times of self-punishment and fear of negative affects; defensive operations demand considerable distortion of her representations of herself and others through splitting and idealisation; perception of others grants them little autonomy, and her capacity for empathy is quite restricted; attachment is compromised by the lack of internalised good objects alongside the dominant fear of losing her external good objects. The degree of misunderstanding that has arisen in the short exchanges with referrers suggests that her communications may be equally poorly integrated, but this is best decided through direct experience. Overall, and despite Alice's apparently promising career and tendency to talk very confidently about her abilities as a high-flyer, integration is consistently in the low-to-moderate range. Should psychotherapy be considered as a treatment option for Alice, this will have a bearing not only on its aims, but also its intensity and duration.

Conflict

Alice exhibits some conflict in nearly all of the seven areas listed in the OPD system (Part 1: Box 6). This does not make them equally significant. In Alice's case, the tension between wishes for dependence v. autonomy and the Oedipal/sexual conflicts evidenced seem to have the greatest effect, being central to her presentation and her evident difficulty in being able to recover.

Conclusions

We have sought to demonstrate why the teaching of psychodynamic formulation is important at all levels of medical training. The methods used, primarily small-group teaching and supervision, are substantially the same at each level. However, the emphasis and curriculum change according to trainees’ previous professional development and the objectives at each stage.

Declaration of interest

Since this article was written, C.M. has joined the UK OPD Task Force.

MCQs

-

1 1 SHOs should be able to:

-

a assess a patient's integration

-

b list precipitating factors

-

c take a personal history

-

d identify maintaining factors

-

e teach formulation to others.

-

-

2 Formulation is taught in small groups because:

-

a it is easy to video the discussion

-

b students’ differing needs can be accommodated

-

c links with a range of practical experience can be examined

-

d it makes role-play less embarrassing

-

e they encourage frank discussion.

-

-

3 The OPD system can be learned from:

-

a correspondence courses

-

b case discussion

-

c a DSM–IV supplement

-

d a published manual

-

e an interactive website.

-

-

4 Basic psychodynamic formulation skills are useful for:

-

a medical students

-

b general psychiatrists

-

c pharmacists

-

d foundation-year doctors

-

e general practitioners

-

-

5 Common errors in formulation include:

-

a being excessively descriptive

-

b containing inadequate analysis

-

c being too specific to the particular patient

-

d providing an incorrect diagnosis

-

e being pejorative about the patient.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T | a | T |

| b | T | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | T | c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | T | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.