Introduction

Past research has shown that children and young men and women in a range of African countries, including Sierra Leone (Christensen & Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008; Peters & Richards Reference Peters and Richards1998), Liberia (Maclay & Özerdem Reference Maclay and Özerdem2010), and Kenya (Kagwanja Reference Kagwanja2005), have participated in violent protests and armed conflict to contest their “blocked social mobility,” or enduring “immaturity” (Abbink Reference Abbink, Abbink and Van Kessel2005; Maclay & Özerdem Reference Maclay and Özerdem2010). Youths involved in these inter-generational struggles often perceive violence as a means to emancipate themselves and create avenues for gaining political participation and influence as well as societal significance. Besides being portrayed as a war of “who-is-who” (Marshall-Fratani Reference Marshall-Fratani2006), the violent conflict in Côte d’Ivoire has been traced by some scholars as originating from the escalation of such an inter-generational struggle (Arnaut Reference Arnaut, Abbink and Van Kessel2005, Reference Arnaut2012; Banégas Reference Banégas2007). And it is undoubtedly correct that youths have played an extremely important role on all sides of the conflict (Chelpi-Den Hamer Reference Chelpi-den Hamer2011).

Another important observation to be made in this respect is that in the aftermath of violent conflict, the younger generations’ expectations and aspirations are often not met or even taken seriously (Berckmoes Reference Berckmoes2014; Boersch-Supan Reference Boersch-Supan2012). Young people are often forced back into submissive and dependent roles (see Iwilade Reference Iwilade2017 on the reconstitution of neopatrimonial systems linking youth to patrons in the Niger Delta). Many young people in post-conflict societies therefore continue to be politically marginalized and excluded from the centers of political power and decision-making. On top of that, they often face serious social and economic constraints and challenges (Boersch-Supan Reference Boersch-Supan2012; Oosterom Reference Oosterom2018). When youths experience re-marginalization, violence may once again become a “bargaining chip” (Maclay & Özerdem Reference Maclay and Özerdem2010), as evidenced, for example, by the remobilization of ex-combatants in the postwar period in Sierra Leone (Christensen & Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008).

Against the backdrop of renewed violence, youths are commonly perceived as a security threat in countries emerging from violent conflict. In particular, young women and men who are unable to enjoy or resume an education or gain meaningful access to the post-conflict economy are often argued to be potential spoilers of peace processes (Haer & Bohmelt Reference Haer and Böhmelt2016). It is therefore a worrying observation that in many post-conflict countries, youth unemployment rates are often very high. Illustratively, in Côte d’Ivoire, approximately 25 percent of youths (aged 15 to 24 years old) remain unemployed. An additional 16 percent are not involved in education, employment, or any type of training program (Lefeuvre et al. Reference Lefeuvre, Roubaud, Torelli and Zanuso2017 [2016 data]). Given the precarious and challenging socio-economic situation of the youths in post-conflict Côte d’Ivoire, it is hardly surprising that there has been a noticeable increase in youth delinquency and criminality since the end of the 2010–2011 post-electoral crisis (Konaté Reference Konaté2017; Kouamé Yao Reference Kouamé Yao2017). In urban areas—and particularly in Abidjan—youth gangs, locally called enfants-microbes (or simply microbes), have turned to violence and criminality to make a living. Many microbes are school dropouts without any socio-economic prospect who have been traumatized by the country’s violent past (Akindès Reference Akindès, Salahub, Gottsbacher and de Boer2018; Kouamé Yao Reference Kouamé Yao2017). The dynamics described in Côte d’Ivoire are, however, not unique to this country, and similar problems have occurred in other post-conflict countries in Africa, such as Sierra Leone (Kunkeler & Peters Reference Kunkeler and Peters2011), Liberia (Maclay & Özerdem Reference Maclay and Özerdem2010) and D.R. Congo (Vuninga Reference Vuninga2018).

While youths have generally played an important role in most African conflicts, it is worth highlighting that most young people do not get involved in (post-) conflict violence (King Reference King2018; McLean-Hilker & Fraser Reference McLean-Hilker and Fraser2009). Research on violent group mobilization nonetheless shows that these youths often face the same challenges and constraints that “push” some of their peers to (re)turn to violence (Guichaoua Reference Guichaoua2010; Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008). These studies thus show that the decision to take up arms is much more contingent than is commonly assumed upon the collective and individual opportunities and constraints that youths face at a specific moment in time (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012; Berckmoes Reference Berckmoes2014; Christensen & Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008; Oosterom Reference Oosterom2019; Vigh Reference Vigh2006). Still, many scholars ignore how the same young women and men can produce both violence and non-violence, depending on situational and temporal cues (see Iwilade Reference Iwilade, Iwilade and Ebiede2022). By relying on cases where youths have turned to violence, they not only risk overstating the threat posed by socio-economically and politically marginalized youths, but they also tend to overlook what post-conflict societies and politics can learn from young men and women who have not (yet) participated in violence (see also Manful Reference Manful2022, who more generally observes that the perspectives and experiences of youths are often made peripheral or dealt with one-sidedly in research on conflict and peace in Africa). Our aim in this article is therefore to demonstrate that broadening the approach to include young women and men irrespective of their past or current use of violence is essential if we want to assess and mitigate the risk of renewed violence in contexts where peace remains fragile. To do so, we examine youths’ perceptions of what a peace process has achieved and their expectations of what the future will hold in the case of Côte d’Ivoire, a country that experienced large-scale violence during the 2002–2007 civil war and in the wake of the 2010 presidential elections, but that has remained relatively peaceful since that time (for other studies focusing on youths beyond youth-related concerns only, see King et al. Reference King, Harel, Burde, Hill and Grinsted2020; Manful Reference Manful2022). Whereas their perceptions may or may not differ substantially from a more objective assessment of their reality, youths, like people in general, usually act and react based on their perceptions rather than the actual situation (Langer & Mikami Reference Langer, Mikami, Mine, Stewart, Fukuda-Parr and Mkandawire2013).

In contrast to ethnographic studies, surveys, or interview-based research with small samples of young men and women, often with a history of participation in violence, our methodological approach consisted of collecting written essays from 905 lower and higher secondary students in the cities of Bouaké and Abidjan (for other examples of essay-based research, see Bentrovato Reference Bentrovato2014, Reference Bentrovato2015). This innovative approach enabled us to collect rich, qualitative data among a large and heterogeneous section of adolescents. Because of its large sample size and the addition of a limited set of standardized background questions, we examine this heterogeneity in this article. Since research participants were all secondary-educated urban youths, some of the results may not apply to out-of-school and/or rural youths, however. Where it is relevant, we reflect on potential differences using comparative survey data. Similarly, we compare the views and experiences of these students to those of the adult population.

In the literature review, we briefly discuss the individual and collective circumstances that inform youths’ decisions to participate in post-conflict violence. Next, we outline Côte d’Ivoire’s inter-generational struggle. This is followed by a discussion of our methodology and data collection methods. In the results section, we analyze the students’ essays, focusing particularly on their views of the current and future situation in the country. To conclude, we reflect on the singularity of educated youths’ perceptions of the risks, challenges, and opportunities of the peacebuilding process in Côte d’Ivoire within a broader context.

Youth and Violence in Conflict-Affected Societies

A common and widely researched hypothesis is that high fertility and large youth cohorts, so-called “youth bulges,” make countries more prone to experience (renewed) violent conflict, especially when young people lack socioeconomic opportunities (Cincotta & Weber Reference Cincotta, Weber, Goerres and Vanhuysse2021; Urdal Reference Urdal, Brown and Langer2012; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2010; see Olawale & ‘Funmi Reference Olawale and ’Funmi2021 for an Africa-focused review; and Haer & Bohmelt Reference Haer and Böhmelt2016 for a study focusing on conflict recurrence in particular).Footnote 1 At the micro-level too, such a lack is commonly identified as a “grievance” or a “push factor” which may contribute toward explaining patterns of participation in violent conflict (Haer Reference Haer2019; Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008). Relatedly, frustrations among today’s youth may arise as their transition toward adult status, usually obtained through marriage, parenthood, and/or secure jobs, is increasingly prolonged or blocked altogether (Honwana Reference Honwana, Foeken, Dietz, de Haan and Johnson2014; Abbink Reference Abbink, Abbink and Van Kessel2005; McLean-Hilker & Fraser Reference McLean-Hilker and Fraser2009). Particularly in Africa’s male-dominated, gerontocratic political systems, such experiences of “blocked social mobility” may contribute to causing or worsening inter-generational tensions and conflict (Boersch-Supan Reference Boersch-Supan2012). Indeed, when young men and women lack prospects, they risk becoming “mobilizable” for violent action in their attempt to overcome their “stuckness” (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012). The Revolutionary United Front’s strategy in Sierra Leone, for instance, consisted of targeting socially excluded, poor youth for mobilization into their “people’s army” (Peters & Richards Reference Peters and Richards1998). Other identified grievances include ethno-religious or political frustrations (Olawale & ‘Funmi Reference Olawale and ’Funmi2021). Besides poor employment prospects, feelings of being discriminated against motivated youths in Niger to join the Tuareg rebel movement, MNJ, for instance (Guichaoua Reference Guichaoua2010). Escaping insecurity is another push factor. Jaremey McMullin (Reference McMullin2022) describes in this respect how one young man in Liberia joined a pro-Taylor militia seeking personal security after having lost his father and being separated from his mother.

Although these studies are not mutually exclusive, other scholars have emphasized the importance of “pull factors” or incentives, such as money, power, fame, or belonging (for reviews of this literature, see Guichaoua Reference Guichaoua2010; Haer Reference Haer2019; Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008). Illustratively, ex-combatants in Sierra Leone shared how not only money and food but also a sense of “togetherness” motivated them to re-join former militia networks (Christensen & Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008). In many conflict-affected societies, children and youths do not join voluntarily, however, but are coerced to join armed groups (see Blattman Reference Blattman2009 on abduction in Uganda; Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008 on Sierra Leone). Drawing on the existing literature, William Murphy (Reference Murphy2003) conceptualized three mobilization models: the “revolutionary youth,” the “delinquent youth,” and the “coerced youth” models. Whereas the latter model views youths as passive victims of conflict and war, the first two models ascribe a degree of agency to the youths, which means that they decide themselves whether to act either as idealists or as criminal opportunists. It is equally important, however, to highlight that youths may positively contribute in diverse and non-violent ways to challenging the societal and political status quo and breaking cycles of violence (McEvoy-Lévy Reference McEvoy-Lévy2001; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2010). Thus, for example, young people in Zimbabwe used cyberspace to coordinate non-violent resistance against the Mugabe and Mnangagwa regimes (Gukurume Reference Gukurume2022), and young Nigerian community vigilantes have at times contributed positively toward managing farmer-herder conflicts in the country (Adzande Reference Adzande2022).

Moreover, youths in unstable and/or conflict-affected societies are often caught between agency and structure, opportunities and precarity (McMullin Reference McMullin2022). Building upon Henrik Vigh’s (Reference Vigh2006) concept of “social navigation,” anthropologists have studied how youths “navigate” the uncertainties and indeterminacy of the (post-) conflict society by predicting and foreseeing the unfolding of the political and economic environment (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012; Boersch-Supan Reference Boersch-Supan2012; Oosterom Reference Oosterom2019). Whether or not youths become “mobilizable” or “politicized,” then, depends on their reading of the context and their responses to, and engagement with, the constraints they face at a particular moment in time (Both et al. Reference Both, Mouguia, Poukoule, Tchissikombre, Wilson, Iwilade and Ebiede2022; Iwilade Reference Iwilade, Iwilade and Ebiede2022). Lidewyde Berckmoes (Reference Berckmoes2014), for instance, describes how one young man in post-conflict Bujumbura at first decided to abstain from political involvement, fearing retaliation, until he needed to provide for a child. Similarly, the young Merveille only joined the Seleka rebellion in the Central African Republic once her husband abandoned her during her third pregnancy (Both et al. Reference Both, Mouguia, Poukoule, Tchissikombre, Wilson, Iwilade and Ebiede2022). Former fighters in Sierra Leone, for their part, tactically maneuver between opposing politicians to meet their needs (Christensen & Utas Reference Christensen and Utas2008). Performing such “watermelon politics” (symbolizing support for the SLPP, characterized by the color green, while voting for the APC, associated with the color red) is much to the discontent of other young people in the country, however, as expressed in a popular song on the topic which was released during the 2007 election campaign (Shepler Reference Shepler2010).

In order to understand the ways in which youths aim to get involved in society and especially to understand whether and when youths see violence as useful, appropriate, and possibly the only means to make themselves heard and gain relevance in society, we need to examine the challenges young people perceive for themselves and society at large. Before turning to the analysis of the perceptions of young Ivoirians concerning their country, we briefly discuss Côte d’Ivoire’s conflict history.

Peace and Conflict in Côte d’Ivoire

Conflict in Côte d’Ivoire

In 2002, Côte d’Ivoire was torn apart by a civil war that de facto split the country in two. To a large extent, the civil war was the outcome of escalating struggles over rural property rights set in a context of economic crisis and a shift in the balance of power toward migrant communities in the early days of multipartyism (Boone Reference Boone2009; Côté & Mitchell Reference Côté and Mitchell2016). After years of state-promoted migration from the northern parts of the country and neighboring states to the southeastern and later on southwestern regions, land became increasingly scarce. This gave rise to anti-foreigner and anti-northerner sentiments among the autochthonous populations of the coastal and forest regions of southern Côte d’Ivoire, who contested the user-rights affirming policies put in place by the country’s founding father, Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012; Bøås Reference Bøås2009; Boone Reference Boone2009; Côté & Mitchell Reference Côté and Mitchell2016). Relations further deteriorated in the late 1980s due to the decline of the Ivoirian cacao industry. While opposition among the indigenous groups had originally been bought off with the gains of the heavy taxes on cacao production, Houphouët-Boigny’s system of clientelism was no longer sustainable once the patronage resources dried up (Banégas Reference Banégas2006; Bøås Reference Bøås2009; Boone Reference Boone2009). The return of a multiparty system in 1990 and the subsequent death of Houphouët-Boigny in 1993 further intensified these issues. In an attempt to exclude rivals and build election-winning majorities, political leaders exploited a discourse of autochthony. More specifically, Houphouët-Boigny’s successor and leader of the ruling Parti Démocratique de Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI), Henri Konan Bédié, turned to the ideology of Ivoirité (“Ivoirianness”) to increase his chances of winning the 1995 elections. Allegedly introduced to promote a sense of cultural unity, he used Ivoirité as a pretext to amend the 1994 electoral code and, indirectly, exclude his former party member, Alassane Ouattara, from the presidential race. Ouattara, of northern origins, had left the PDCI to lead the newly established liberal party, Rassemblement des Républicains (RDR). Bédié feared being outvoted by Ouattara because of the strong appeal of the RDR among the many internal and regional migrant workers living in Côte d’Ivoire, in contrast to the principally southern-based PDCI (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012). The new electoral code made it mandatory that presidential candidates had to be born from an Ivoirian mother and father, and had to have lived in Côte d’Ivoire for the five years preceding any presidential election. On these grounds, Ouattara’s candidacy was effectively nullified; not only did he live in the USA during some time in the five years preceding the elections, but he was alleged to have Burkinabe roots.

In office, Bédié continued his exclusionary politics by revising the Code Foncier (law on land tenure) with the support of the Front Populaire Ivoirien (FPI), a party that for a long time had advocated autochthonous land rights. The new 1998 law authorized members of local communities to confirm the initial allocation of land ownership rights (Bøås Reference Bøås2009; Boone Reference Boone2009, Reference Boone2018; Côté & Mitchell Reference Côté and Mitchell2016). Most fundamentally, however, Ivoirité espoused a nativist discourse that redefined citizenship to include only those who were considered “Ivoiriens de souche,” that is, Ivoirians who could trace back their ancestral origins to a village in Côte d’Ivoire. In doing so, it denied the citizenship claims of people with a migration background, as well as of Ivoirians belonging to groups that shared certain cultural or religious traits with immigrants. Notwithstanding their actual ethnic and religious diversity, these groups were lumped together under the generic category of “Dioula,” which came to mean interchangeably northerner and Muslim (Miran-Guiyon Reference Miran-Guyon2016; Boone Reference Boone2009; Ceuppens & Geschiere Reference Ceuppens and Geschiere2005). As a result, northern “autochthons” were considered “strangers” or “foreigners”—at best Ivoirians of immigrant ancestry—in their own country (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012; Bah Reference Bah2010; Banégas Reference Banégas2006; Konaté Reference Konaté2017; Miran-Guyon Reference Miran-Guyon2016). Disgruntled by such exclusion, northern mutineers led by General Robert Guéi ousted Bédié from power in December 1999. One year after the coup (2000), new presidential elections were organized—still excluding Ouattara from participation—which were won by Laurent Gbagbo, president of the FPI. Whereas Gbagbo no longer reverted to Ivoirité as such, the autochthonous discourse remained vibrant as Gbagbo further supported the ethnic land rights of “autochthons” (Boone Reference Boone2018; Ceuppens & Geschiere Reference Ceuppens and Geschiere2005).

The persistent and deepening discrimination against the north led to another coup d’état in 2002 by northern-dominated rebel forces, who managed to occupy the northern regions. They only relinquished control in 2009 after the establishment of a government of national reconciliation in the framework of the Ouagadougou Peace Agreement (2007). Another key element of that agreement was the acceptance of Ouattara’s candidacy in the next presidential elections, which were eventually held in 2010. When Ouattara won those elections, Gbagbo contested the results, resulting in renewed violence. The post-electoral crisis only came to an end once Gbagbo was forcibly removed from power in April 2011. Subsequently, Gbagbo was indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of crimes against humanity—yet he was acquitted in 2019 because of insufficient evidence demonstrating his complicity.

Since contested citizenship claims were at its core, the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire is often described as a war of “who-is-who” (Marshall-Fratani Reference Marshall-Fratani2006; Bah Reference Bah2010). Besides identity-related grievances, inter-generational tensions played an important role as well (Banégas Reference Banégas2007; Marshall-Fratani Reference Marshall-Fratani2006:29). Among the autochthons who contested past land rights transfers, there were many youths. Having left their villages in search of better prospects in the city, many young men and women returned disillusioned by the subsequent urban employment crisis (Banégas Reference Banégas2007). When they returned to their rural places of origins, they found that their ancestral lands were no longer available to them. In their eyes, their parents had illegally sold or given away their lands to supposed “foreigners.” To demand the restitution of their alleged rights and renegotiate their status, many youths joined groups such as the Alliance of Young Patriots for the National Surge (commonly called Young Patriots), which resorted to violence in this respect. Besides contesting user-affirming land rights, the Young Patriots’ rejection of the neo-colonial/imperial influence of the former colonial power, France, appealed to many youths. Their discourse circulated widely via public discussion fora (so-called parlements and agoras), resulting in an estimated 25,000 youngsters joining the “patriotic galaxy” (Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012). Because of the similarities between their discourse and that of national liberation that embodied the political project of Laurent Gbagbo, the Young Patriots were largely perceived and presented as idle youths among the general populace, instrumentalized by the ruling party under the guise of a supposed “rejuvenation of the nation” (Akindès & Fofana Reference Akindès and Fofana2011; Arnaut Reference Arnaut2012; Banégas Reference Banégas2006, Reference Banégas2007; Konaté Reference Konaté2003).

Notably, many militant youths came from the ranks of the Fédération Estudiantine et Scolaire de Côte d’Ivoire (FESCI; Student and School Federation of Côte d’Ivoire), a radical student movement with military undertones that was originally created in 1990 in response to the repression of students protesting against the country’s one-party state and Houphouët-Boigny’s system of clientelism (Arnaut Reference Arnaut, Abbink and Van Kessel2005; Konaté Reference Konaté2003). The Young Patriots, notably, were led by former FESCI secretary Charles Blé Goudé.Footnote 2 Guillaume Kigbafori Soro, one of the figureheads of the 2002 rebellion forces, was also a former FESCI secretary.Footnote 3 A Catholic Sénoufo (northern ethnic group that is part of the larger ethnolinguistic group of the Gur), it is interesting to note here that Soro’s involvement refutes the common perception of the rebels as a homogenous group of Muslim Dioulas—more generally, the rebellion represented an ethnic and religious mix rather than being the exclusive preserve of northerners; likewise the patriotic galaxy was comprised both of southern “autochtons” and northerners (Miran-Guiyon Reference Miran-Guyon2016).

Fragile Peace

Since Ouattara’s formal inauguration in May 2011, Côte d’Ivoire has been able to record strong economic growth rates. Building on his economic record, Ouattara’s 2015 reelection campaign was built around the themes of achieving material progress, industrialization, and international prestige—l’émergence à l’horizon 2020 (a “booming” economy by 2020). Yet, economic success was slow to trickle down to all layers of society, causing disgruntlement among the larger population; in 2015, the number of poor households (46 percent) had only reduced by 5 percent compared to 2011 (51 percent) (Akindès Reference Akindès2017; Konaté Reference Konaté2017; Piccolino Reference Piccolino2018). Young Ivorians remained disgruntled as well. Despite drafting a national youth policy in the immediate aftermath of the post-electoral crisis, with a special focus on generating opportunities for youth employment, the policy was only adopted in late 2016 and lacked a comprehensive and coherent framework (Lefeuvre et al. Reference Lefeuvre, Roubaud, Torelli and Zanuso2017; OECD 2017).

In terms of reconciliation, Ouattara’s policies focused on building social cohesion among local communities through a variety of initiatives overseen and supported by the National Program for Reconciliation and Social Cohesion (2012–2020) (Piccolino Reference Piccolino2019). Several youth initiatives were set up as well, including an ICTJ-UNICEF project that aired a youth-targeted radio program discussing the root causes of youth mobilization (Ladisch & Rice Reference Ladisch, Rice, Ramírez-Barat and Duthie2017). Still, reconciliation remains a major challenge. Whereas victims were heard as part of the Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Commission Dialogue, Vérité et Reconciliation; CDVR)—including 757 children, although their testimonies have been reduced to statistics only (Ladisch & Rice Reference Ladisch, Rice, Ramírez-Barat and Duthie2017)—the commission largely failed to reach the larger population and was subject to political influence. Not only were the hearings not broadcasted, but the report was also censored and not released until two years after its conclusion (Babo Reference Babo2019; Piccolino Reference Piccolino2018).Footnote 4 Making matters worse was the fact that only supporters of Gbagbo and the patriotic galaxy were prosecuted, despite the fact that both sides had committed atrocities, crimes, and human rights abuses, thereby propagating (at least among the Gbagbo supporters) a sense of victor’s justice (Babo Reference Babo2019; Piccolino Reference Piccolino2018, Reference Piccolino2019).Footnote 5 In addition, many of the former rebel commanders were appointed as elected officials, members of the armed forces, or civil servants. Illustratively, in 2017, former rebels held an elected position in about one in five sub-prefectures of the former rebel-controlled northern half of the country (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Piccolino and Speight2021). Yet, tensions have increased in recent years between the Ouattara government and the former rebels who were integrated into the security forces, as evidenced by the many military uprisings that have taken place under Ouattara’s presidency (Bjarnesen & van Baalen Reference Bjarnesen and van Baalen2020; Babo Reference Babo2019; Martin Reference Martin2018).

Finally, it is worth noting that important causes of the violent conflict and enduring political instability remain unaddressed. Whereas the electoral code has been amended, conflicts over ancestral land rights persist (Boone Reference Boone2018). Notably, a 2015 household survey shows that land disputes are considered the main source of conflict and tensions among groups (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015). More fundamentally, however, as Richard Banégas and Camille Popineau have argued, intergenerational tensions persist as yesteryear’s gerontocratic order—or “korocracy” in Ivoirian slang—has reproduced itself (Banégas & Popineau Reference Banégas and Popineau2021). On October 31, 2020, Ouattara (then 78 years old) was reelected for a third term, despite earlier promises to pass power on to a new generation. Although he received 94.3 percent of the vote (as announced by the Electoral Commission and confirmed by the Constitutional Council), his main contenders boycotted the elections to contest the legality of his third term.Footnote 6 Among these contenders were former president Henri Bédié (then aged 86) and Pascal Affi N’Guessan (then aged 67). The former had withdrawn his support for Ouattara’s 2010/11 winning coalition (the ruling Rassemblement des houphouëtistes pour la démocratie et la paix, made up of Ouattara’s RDR, Bédié’s PDCI, and former rebels) and put forward his own candidacy once it was decided that, for the second time in a row, the presidential candidate came from within the RDR ranks. Pascal Affi N’Guessan, on the other hand, ran on the ticket of Gbagbo’s (then aged 75) FPI, who himself had been disqualified as a candidate because of legal reasons (the ICC indictment).Footnote 7 Markedly, Guillaume Soro, considered a representative of younger generations, did not figure among the candidates. Like Gbagbo’s, Soro’s candidacy had been rejected for legal reasons.Footnote 8 For several years already, the Ouattara administration is speculated to have thwarted Soro’s presidential ambitions by politically marginalizing the former rebel leader and ex-president of the national assembly (Babo Reference Babo2019). So far, it seems that “the ambition of the emerging generations” has effectively been blocked in the country (Banégas & Popineau Reference Banégas and Popineau2021:463).

Data & Methodology

To understand the ways in which youths, both as a group and as individuals, perceive the current and future situation of themselves and their country, we collected original data among a sizeable and heterogenous body of youths. Secondary schools provide an ideal setting to interact with large groups of adolescents from varying backgrounds. Therefore, we randomly selected secondary schools on the basis of a list of all schools in the cities of Abidjan and Bouaké. Abidjan, located in the south, is the largest city and economic heart of the country. Bouaké, the second largest city, is in the north-central part of the country and was the stronghold of the rebels during the civil war (2002–2007). To ensure the inclusion of both public and private schools located in disadvantaged and popular neighborhoods as well as in more well-off areas, we stratified schools by neighborhood, size, and type of school.Footnote 9 While we planned to use a sample of five secondary schools in each city, the final selection of schools in Abidjan consisted of seven schools, as two schools only provided one level of education (higher/lower secondary education). Within each school, we selected two groups of students, with the permission of the principal and relevant teachers: one in their final year of lower education (‘la troisième’; expected age of 16), and one group in their final year of higher secondary education (‘la terminale’; expected age of 18). Importantly, students decided themselves whether they wanted to participate. Many students may, however, have felt obliged to participate because of the subtle power dynamics at play in a school setting (Manful Reference Manful2022). To enhance the students’ sense of control, we therefore avoided using forced responses. Some students did effectively leave one or more questions blank. Given the age of the students, parental consent was obtained as well (no parents objected).

The students took part in an essay writing exercise that we set during the teaching time of history-geography or human rights and citizenship education (education aux droits humaines et à la citoyenneté; EDHC); sampling from an existing school assignment was not possible. The essays were based on the following questions: (1) how would you describe the current state of peace in Côte d’Ivoire? And (2) what can we do to ensure that your generation and all the following generations will live together in peace? By answering open-ended, non-directive questions, students could develop their own core ideas in relation to peace and (in)stability in the country. Prior to data collection, the format was piloted to ensure comprehension. In addition to the essay questions, a limited number of survey questions was included to collect demographic data, as well as close-ended questions/statements with respect to peace in Côte d’Ivoire, in particular: (1) I think that the current state of peace in the country is (1= not stable at all, 2 = not stable, 3 = stable, 4 = very stable); (2) When I think about the future of Côte d’Ivoire, I mainly feel (1= very pessimistic, 2 = pessimistic, 3 = optimistic, 4 = very optimistic); and (3) Do you think that Côte d’Ivoire will remain peaceful in 2020? (yes or no). These responses enabled us to examine and explain patterns in the data.

The actual essay writing was explained and overseen by the first author between October and December 2017. Whereas many teachers remained present in the classroom, they were not involved in the data collection process and at no point had access to the essays. Upon the explicit request not to assist in the data collection, they usually retreated to the background, correcting assignments or preparing for upcoming classes instead. Indeed, ensuring that students felt free to share their honest views and perceptions was deemed crucial. For the same reasons, we did not collect any identifying information. In this way, we aimed to minimize social desirability bias. Still, it remains possible that some students did not share their frank and complete opinions, whether because of any unaddressed fears or doubts regarding anonymous treatment, their (perceived) inability to clearly communicate their views in writing, or even disinterest in the exercise.

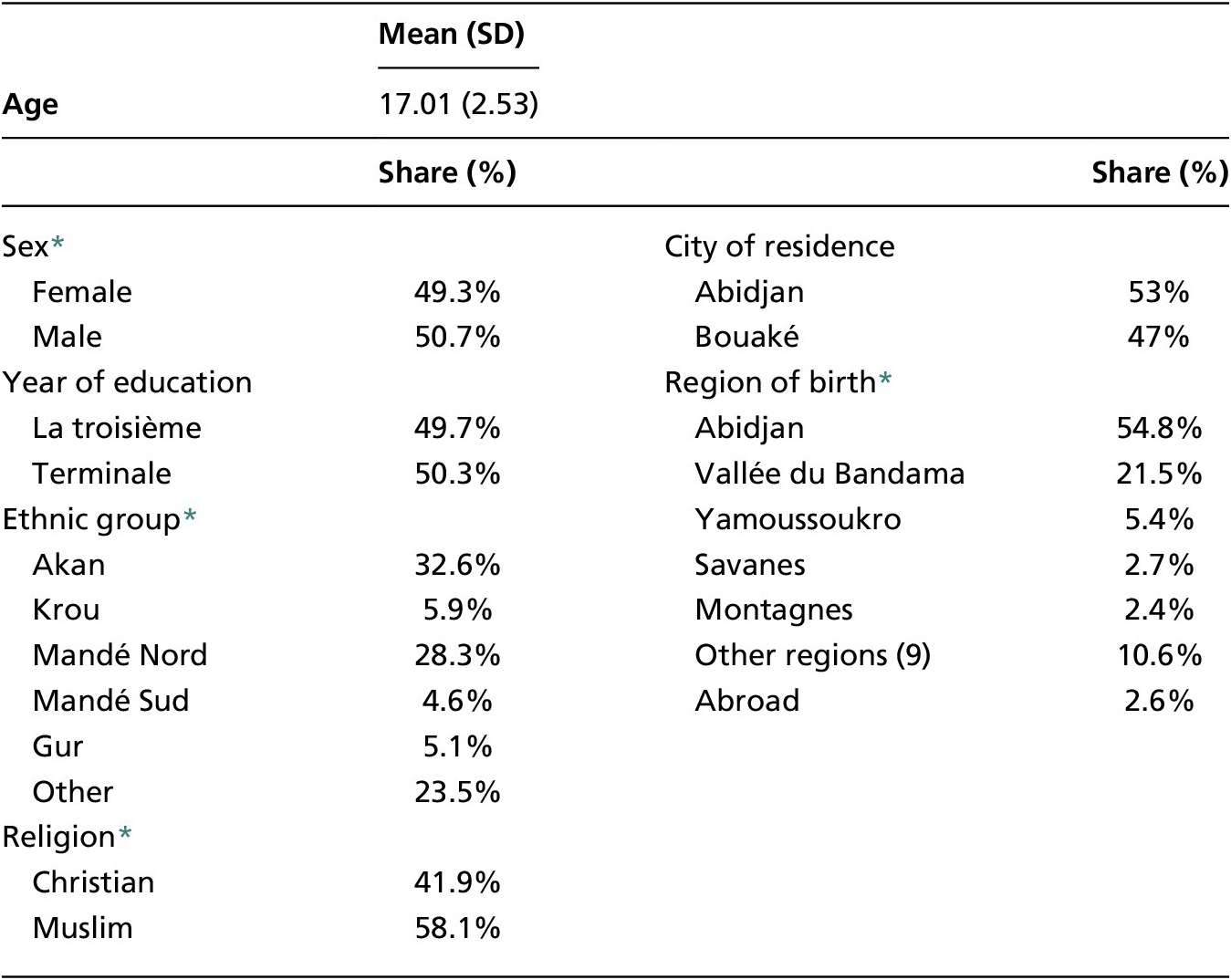

In total, 905 students participated. The essays were written in French, the language of instruction in Côte d’Ivoire. On average, the essay questions (which included two other open-ended questions not examined here) were completed in 37 minutes (with a standard deviation of 10 minutes) and varied from single sentence responses (minimum word count of 51 words) to more elaborated responses (maximum word count of 659; compared to an average word count of 263). Grammar and spelling were generally rather poor, with a lot of names and words written phonetically. The oldest student was 26 years old (many students are overage for their grade), compared to a mean age of seventeen years old (see Table 1). The sample included roughly the same number of female and male students. In terms of ethnic background, most students identified with the ethnic groups of the Akan (32.6 percent) and Mandé Nord (28.3 percent). Almost one in four students (23.5 percent) did not identify with any of the five major ethnic groups of Côte d’Ivoire (Akan, Krou, Mandé Nord, Mandé Sud, or Gur). Twenty-two students indicated that they were born outside of Côte d’Ivoire. With respect to religion, about 60 percent of students were Muslims, compared to about 40 percent Christians. Whereas 67.6 percent of students attended a private school, there were important variations in the learning environment among private schools. Illustratively, class sizes varied from 29 students (Abidjan, Cocody) to 58 (Abidjan, Yopougon). Class size tended to be larger in Abidjan than in Bouaké. While many of the participating students were relatively poor, they were not among the most destitute youths in the country, as evidenced by their school enrollment. In Côte d’Ivoire, 36.6 percent and 13.4 percent of school-aged youths nationwide complete lower and higher secondary education, respectively (UIS estimations, 2020).Footnote 10 Although the opportunity costs of the adolescents in our sample could therefore be considered higher than the costs for out-of-school youths (as evidenced by the microbes), it is interesting to note that household surveys show that relatively educated Ivoirians (having at least completed secondary education) feel more discriminated against than others (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015; Afrobarometer Round 7 2017). To further assess the singularity/similarity of the views of educated, urban adolescents compared to out-of-school youth, rural peers, and the adult population, we juxtapose reported views and opinions in the analysis section with data from comparative surveys. We use in this respect household data collected in 2015 by Ivoirian authorities (Enquête sur le Niveau de Vie des Ménages, ENV; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015), Afrobarometer data from Round 7 (2017), and data from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative on peace and education in Côte d’Ivoire, which, uniquely, were collected among 12 to 26 year old youths one year prior to our research (HHI data; Vinck et al. Reference Vinck, Pham and Balthazard2016). While these data are of interest, it is important to note that any apparent differences or similarities between results could be attributed to changes in context over time and differences in survey approach.

Table 1. Student background characteristics

* Percentages exclude missing responses (Sex: 11; Religion: 39; Ethnic group: 85; Region: 58)

Once collected, the essays were digitized. Next, both authors coded the data in the original language (French), making use of the software program NVivo (intercoder reliability of 95%). We combined a deductive and inductive coding strategy. Based on the literature on youth bulges and violence, we identified the main push and pull factors that influence young men and women’s decision to join armed groups, combining this information with insights from past studies regarding the challenges Côte d’Ivoire was facing to establish sustainable peace. As such, we looked for any references to (1) the socioeconomic situation of the country, focusing on youth unemployment in particular, (2) perceptions of security, and (3) views on reconciliation, both at the grassroots and elite levels. We applied different codes for positive or negative assessments of the various factors. More generally, however, we were interested in understanding the students’ overall assessment of the country’s situation, evaluating whether they perceived the country as stable or unstable. In addition, we looked for common and recurring themes while the data was coded.

Analysis

In what follows, we analyze Côte d’Ivoire’s peace process and post-conflict situation through the eyes of the Ivoirian youths. We first present the survey results, followed by an in-depth analysis of students’ perceptions and prospects for peace based on the essay responses. All quotes have been translated from French into English by the authors. Whereas the translations are truthful to the original meaning, grammar and spelling have been corrected in English.

Post-conflict Stability in Numbers

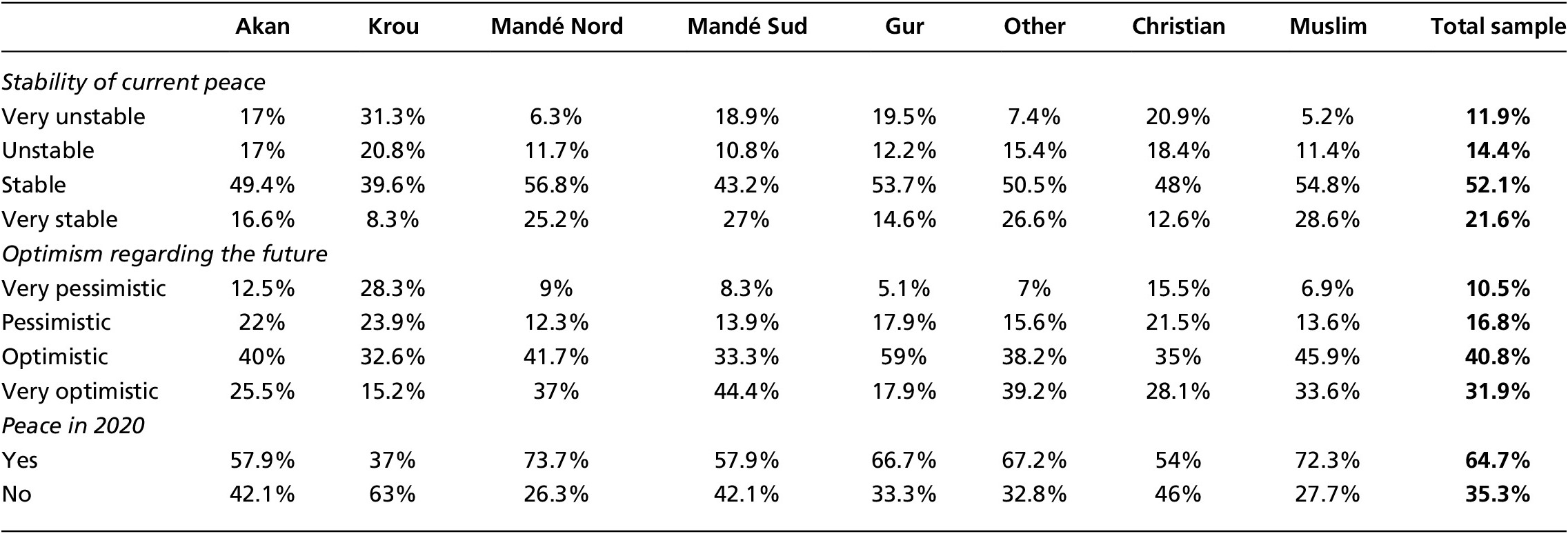

According to the survey results (see Table 2), a large majority of secondary-educated youths considered the country to be “somewhat” (52.1 percent) to “very” (21.6 percent) stable in 2017. Overall, they were also, for the most part, very optimistic (72.7 percent) about the future. As such, more than two-thirds of the adolescents (64.7 percent) believed peace would last after the 2020 elections.Footnote 11 It seems that adolescents were somewhat more positive than the adult population, among whom 56.4 percent at that time believed that the country was going in the right direction (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017).Footnote 12 Even more convincingly, while 46.8 percent of Ivoirians feared that violent conflict or war would recur in 2015 (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015), in our survey this belief was lower, around 35 percent.

Table 2. Youths’ views on (future) peace by ethnic and religious group belonging (%)

Whereas there are no significant differences between male and female adolescents in this respect, older students (often overage for their grade) were marginally more pessimistic regarding Côte d’Ivoire’s future than their younger peers.Footnote 13 Furthermore, we found evidence of a weak, yet significant, association between religious background and students’ assessment of the 2017 peace dividend (Kendall’s τb = –0.270, p<0.001; reference group: Muslims), students’ optimism regarding the future (Kendall’s τb = –0.134, p<0.001; reference group: Muslims) and their belief in a stable peace after the 2020 elections (r = –0.189, p<0.001 reference group: Muslims). More specifically, 37 percent of Christian students were “very” pessimistic regarding the future, compared to only 20.5 percent of Muslim students. Similarly, 72.3 percent of Muslim students thought there would be peace after the 2020 elections, compared to only 54 percent of Christian adolescents. There is also a significant association between these variables and students’ ethnic groups.Footnote 14 Table 2 shows that adolescents identifying as Krou—the ethnic background of ex-president Laurent Gbagbo—were particularly negative regarding the 2017 peace dividend and the future of peace, whereas ethnic groups of northern origins (Mandé Nord, Gur, other) were notably more positive. Although identities are more fluid, it is important to note here that there was a strong association between ethnic and religious group belonging (Cramer’s V = 0.710, p <0.001), with the Akan and Krou ethnic groups being predominantly Christian and the other groups being predominantly Muslim. Similar dynamics can be observed in the Afrobarometer data.

Another finding that stands out is that Christian students living in Bouaké (33.9 percent of all Christian students) were more optimistic regarding the prospects of future peace than Christians living in Abidjan (Cramer’s V = 0.237, p <0.001). There was no such association among Muslim students. These findings could pick up on a “Soro-effect”—remember that the ethno-religious background of the former rebel leader (Christian Sénoufo) challenged the popular perception of the rebels being a homogenous group of Muslim Dioulas. This effect is, most likely, not driven by ethnicity, however, since only nine students in our sample identified as Christian Gurs (the group to whom Sénoufo belong). Instead, place identity and territorial bonds could account for the effect. After all, Bouaké was the rebels’ stronghold at the time of the civil war.

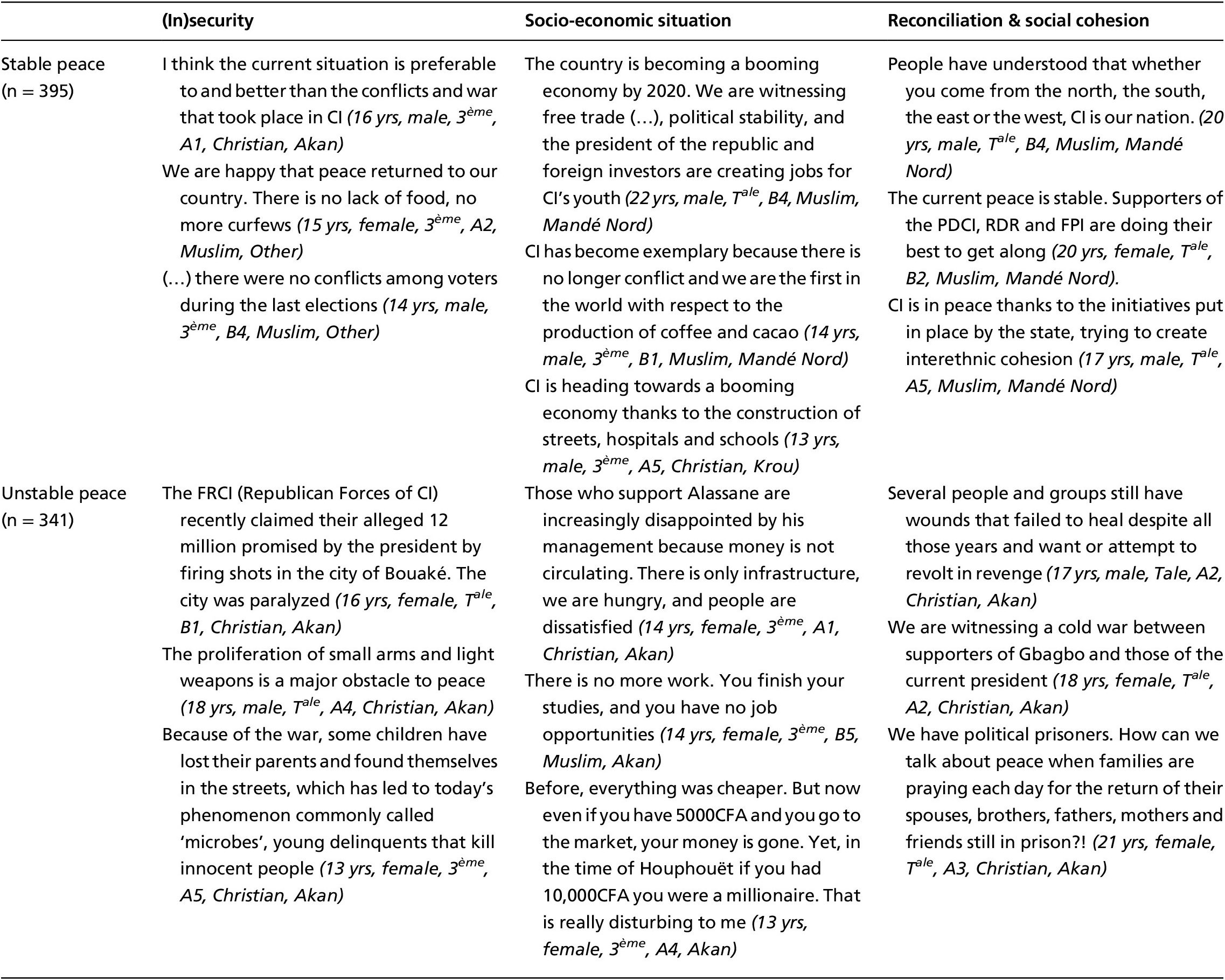

Postwar Stability: In-depth Analysis of Essays

Notably, the proportion of students describing peace in the country in negative terms as part of their essay response was larger than the proportion of students who indicated that the country was somewhat or very unstable as part of the survey. Indeed, when analyzing students’ descriptions of the 2017 state of the country irrespective of their response to the survey question, we identified 395 out of 736 valid essay responses (169 did not answer the relevant question) as positive (i.e., the country was stable/at peace) and 341 as negative (i.e., the country was not stable/at peace). What is more, at least 69 of the 395 students who described peace as stable also showed some restraint or hesitation. Illustratively, one student defined the situation as “a cold peace, because, although Ivoirians are happy, they continue to live in fear of a future war” (23-year-old male, Tale, Abidjan 2, Akan). Another student compared the country to a sleeping volcano: “The country is on one leg. The current situation in Côte d’Ivoire resembles a sleeping volcano. At any moment, it can become active again” (16-year-old female, Tale, Bouaké 2, Christian, Akan). It thus seems that secondary-educated youths are divided when it comes to their assessment of postwar stability. When looking into the reasons for this, adolescents’ views largely diverged on three main themes (see Table 3).

Table 3. Examples of perceptions of peace among adolescents in Abidjan (A) & Bouaké (B), Côte d’Ivoire (CI)

First, there was disagreement over the country’s socioeconomic situation. On the one hand, students praised the country’s economic growth. Among these essays, notably, 64 students reproduced Ouattara’s 2015 electoral discourse of ‘l’émergence à l’horizon 2020’ (a booming economy by 2020). On the other hand, there were many students who complained about the lack of socioeconomic opportunities. Youth unemployment in particular stood out: “There are many youths, maybe more than 70 percent, and we find that [among them] more than 2 million youths have degrees but are jobless,” (21-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 3, Christian, Akan). The student further added that he believed that most positions were “sold.” Relatedly, other adolescents had the impression that particular ethnic groups were favored in the public sector: “The government only favors certain ethnic groups. This favoring affects relations between ethnic groups that do not really contribute to peace” (17-year-old male, Tale, Abidjan 4, Christian, Krou). There were also impressions of religious favoritism: “Within the administration, they are all Muslim” (16-year-old female, 3ème, Abidjan 5, Christian, Mandé Nord). Afrobarometer data show that the adult population is divided on this point as well. The opinion that the government managed the economy “fairly to very well” was held by 49.1 percent, compared to 45 percent who deemed the government fared “fairly to very badly” in this respect. Unemployment was a shared concern, too, as evidenced by a mere 33.6 percent of the adult population expressing satisfaction with the creation of jobs by the government (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017).Footnote 15 In 2015, relatedly, 58.2 percent of the general population were worried about unemployment, increasing to a staggering 81.7 percent in Abidjan (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015). The surveys also confirm to some extent the youths’ perceptions of favoritism in their society: in 2015, 13.7 and 9.4 percent of Ivoirians attested to having been victims of discrimination based on ethnicity and religion, respectively (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015) compared to 12.3 percent and 6.4 percent in 2017 (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017).Footnote 16

Second, students either described their perceptions of whether security had been restored or if it continued to be lacking. Those of the former opinion noted that fighting had ended (n = 44) or explained how daily life could take place uninterrupted (n = 21): “The prevailing climate of peace is good for us, inhabitants. We, students, can go to school again and market activities have resumed” (20-year-old female, Tale, Abidjan 2, Muslim, Mandé Sud). Those who were of the latter opinion identified particular security threats, such as the mutinies within the armed forces (n = 40) and/or the presence of microbes (n = 48). Among youths nationwide, 23 percent considered that their neighborhood at the time was “very” insecure; 20 percent considered security neither good, nor bad (HHI data; Vinck et al. Reference Vinck, Pham and Balthazard2016). Feelings of insecurity were slightly higher among the adult population, among whom close to 30 percent “several times” to “always” felt unsafe when walking in their neighborhood (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017).Footnote 17

Third, adolescents diverged with respect to reconciliation and social cohesion in the country. On a positive note, students wrote about improved inter-ethnic relations, among others, thanks to “awareness raising campaigns in the media, songs and via comedians” (19-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 3, Muslim, Gur). References to elite-level reconciliation, in contrast, were few. Only two students mentioned the CDVR: “Currently, peace is stable in Côte d’Ivoire with the support of organizations created after the war, such as the CDVR” (17-year-old male, Tale, Abidjan 1, Muslim, Mandé Nord). Among those who were less positive, students worried about “peace manifesting itself on the face, but not in the heart” (17-year-old male, Tale, Abidjan 2, Christian, Akan). Among others, persisting tensions were attributed to an apparent climate of victor’s justice, for which peace was argued to be conditional on “both responsibles facing justice, not a single one” (20-year-old male, Tale, Abidjan 2, Christian, Krou). In addition, there were clear expressions of the lingering effects of Ivoirité: “Since Alassane became president, Côte d’Ivoire is full of Burkinabe and other, today even, there are more Burkinabe than real Ivoirians!” (14-year-old male, 3ème, Abidjan 5, Christian, Mandé Sud). Feelings of a lack of social cohesion and inter-group trust were also observed among the general population. In 2015, for instance, less than half of the general population trusted people from other nationalities and ethnic groups (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015).

Similar fault lines were apparent when analyzing students’ reflections on the unfolding socio-political environment. On the one hand, there were students who believed that peace would be consolidated in the years to come: “I believe that the climate of peace in Côte d’Ivoire is more and more under control and that by 2020 we will have a Côte d’Ivoire of understanding, social cohesion, without conflicts and without discrimination” (18-year-old female, Tale, Bouaké 1, Muslim, other). On the other hand, there were students who feared the electoral cycle and its impact on peace and conflict in the country. Among these youths, some showed general skepticism regarding the durability of the peace process: “I don’t believe in peace in Côte d’Ivoire, because each election leads to a conflict. I have the impression that in Africa more generally, but especially in Côte d’Ivoire, every election causes a war” (17-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 2, Christian, Krou). Others were concerned with the 2020 elections in particular, fearing that Ouattara would refuse to leave power: “I often wonder whether we are not heading towards another crisis if the president refuses to leave power” (20-year-old female, Tale, Bouaké 1, Muslim, other). A possible power struggle between Ouattara and Soro was also among the concerns: “Alassane dismissed all allies of Soro (…) and he put aside Soro for Daniel Kablan Duncan as prime minister. But sooner or later, those people will rebel, of that I am very sure” (13-year-old male, 3ème, Abidjan 4, Christian, Akan).

Peacebuilding Strategies

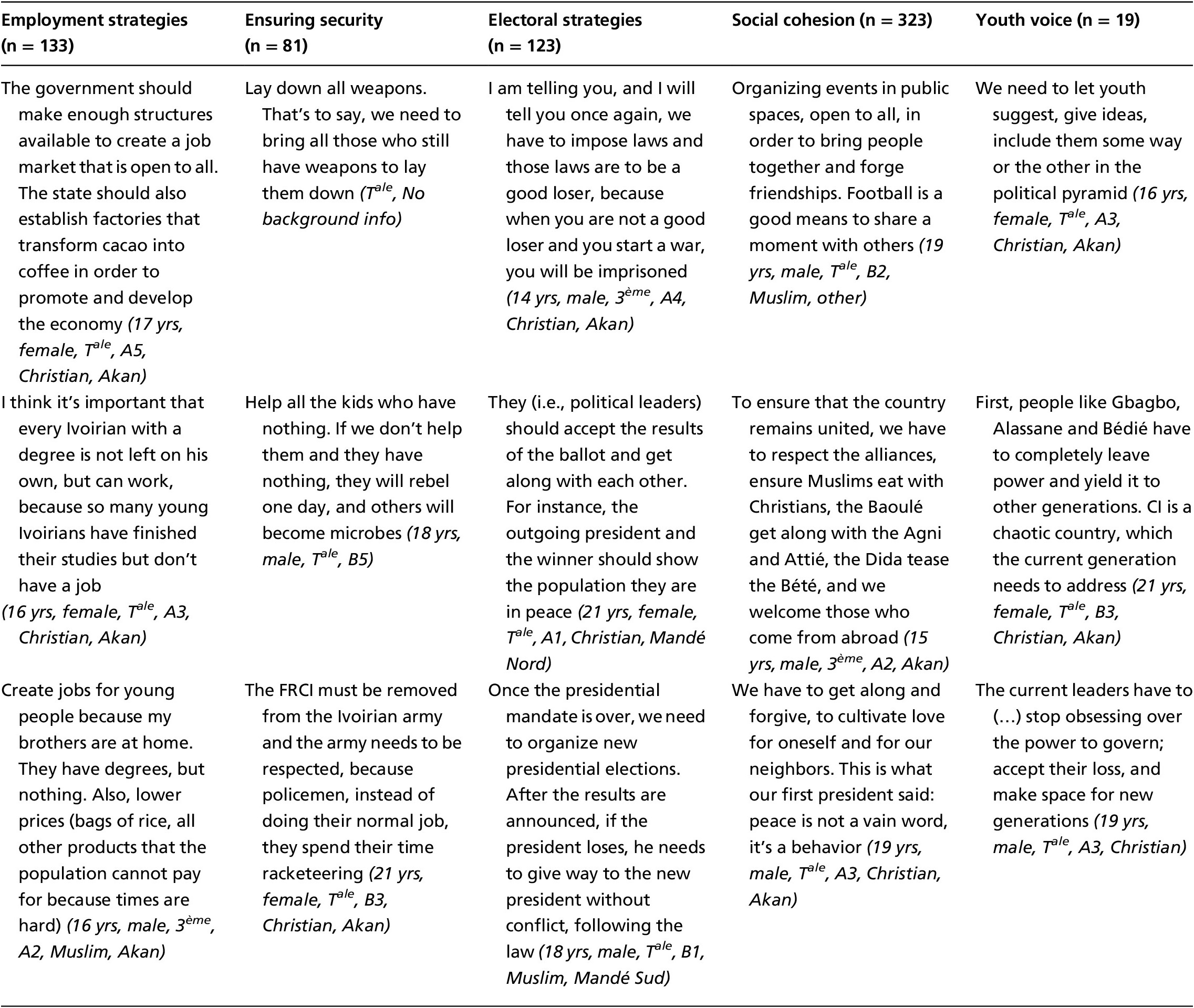

Finally, we turn to the students’ proposed strategies to overcome these challenges and build sustainable peace (see Table 4). It is positive in this respect that survey data shows that, nationwide, youths believed they could positively contribute to peace and reconciliation in Côte d’Ivoire, at least locally; only 5 percent thought that they could not have any impact in this regard (Vinck et al. Reference Vinck, Pham and Balthazard2016). Overall, we were able to discern five main strategies: (1) increasing socio-economic opportunities, (2) improving security, (3) building social cohesion bottom-up, as well as (4) top-down, and (5) passing on power to younger generations. Whereas the first four strategies directly address push factors that characterize the post-conflict environment, the latter strategy is evidence of the persistence of yesteryear’s inter-generational struggle.

Table 4. Examples of strategies for building sustainable peace among adolescents in Abidjan (A) & Bouaké (B), Côte d’Ivoire (CI)

First, the essays included many suggestions of interventions aimed at increasing socioeconomic opportunities in the country (n=133). Indeed, several essays emphasized how creating opportunities would contribute to discouraging youngsters from joining criminal or rebel groups. Students clearly appeared to follow the logic of increasing opportunity costs (Urdal Reference Urdal, Brown and Langer2012). One student explained: “The state should invest in infrastructure for unemployed people, why I say so? Because if a person does not have a job, you can extend them a hand and become a rebel” (14-year-old male, 3ème, Bouaké 1, Christian, other). Although rare, about ten essays stood out for emphasizing the need to “change currency”: “We have to leave the FCFA and demand our complete freedom, without interferences in our internal affairs (…) What does independence mean if we cannot do anything at our own will?” (18-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 3, Muslim, Krou).

A second group of students (n = 81) formulated strategies to improve security in the country. On the one hand, these accounts focused on finding a solution to address the microbes, such as “an association to help the microbes because most of them are orphans (…) facing many difficulties leaving them no choice but to attack to survive” (17-year-old male, 3ème, Abidjan 2, Christian, Krou). Other security-focused essays emphasized the continued need for disarmament in the country.

Third, there was a strong emphasis on building socially cohesive communities. A majority of essays (n = 323) referred to awareness-raising activities aimed at building peace, fostering reconciliation, and promoting forgiveness at the local level. Interestingly, many students appeared to echo the rhetoric of academics and practitioners in the field of peacebuilding by focusing on the need to foster intergenerational change in attitudes and behavior: “We could educate future generations about the consequences of war and the damage that conflicts can cause so that they have a clear idea of how to cultivate peace in our country” (20-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 5, Muslim, Mandé Nord). In contrast to local initiatives, 123 essays referred to interventions at the national level, including elite-level reconciliation: “Political parties and sides should come together and reconcile because they are always talking about reconciliation and peace, but themselves, they are not reconciled” (15-year-old female, 3ème, Abidjan 1, Christian, Akan). In addition, there were pleas to halt ethnic favoritism and represent all groups equally: “Political leaders should not decide based on ethnicity, choosing only graduates from their ethnic group to lead the country (…) each ethnicity should have a representative in the government in order to preserve peace” (17-year-old male, Tale, Bouaké 2, Christian, Akan). Still, most students focusing on top-down peacebuilding strategies underscored the need to accept electoral defeat: “We should organize the elections better and ensure that each candidate accepts the results” (15-year-old male, 3ème, Abidjan 3, Christian, Akan). Relatedly, a limited number of essays suggested “abolishing political parties and creating a single political party instead” (17-year-old female, Tale, Bouaké 3, Muslim, Mandé Nord). These strategies should be understood in the context of the continued veneration of first president and single party-head Houphouët-Boigny in the country: “Things should become again as in the days of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, a president our country will never have again” (14-year-old female, 3ème, Bouaké 5, Muslim, Akan). Among the adult population, too, a significant share of the population (20 percent) agreed that political parties create division and that it is therefore not necessary to have multiple parties (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017).

Finally, several adolescents expressed how important it is to provide a voice to their generation as well as future generations: “We have to ensure they (i.e., youths) are allowed to express themselves. Because we have the right to speak and we have many ideas that can contribute to the development of the country” (15-year-old female, 3ème, Abidjan 3, Christian, Mandé Nord). Others suggested “changing the political leadership” (22-year-old female, Tale, Abidjan 5, Christian, Akan), leaving way for new generations: “All people like Gbagbo, Alassane and Bédié have to leave power completely leaving another generation to take power” (21-year-old female, Tale, Bouaké 3, Christian, Akan). These accounts were few, however.

Except for unemployment, none of the underlying problems that these peacebuilding strategies seek to address were identified by the adult population in 2017 as major priorities for the government to address. Compared to issues related to poverty, health, poor infrastructure, and public service provision, concerns related to street children, security, political instability and ethnic tensions, civil war, and discrimination were hardly raised (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017). It is, however, important to stress here that the framing of the question was significantly different from that in our essay.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we tried to gain more insights into the potential causes and risks of conflict recurrence in Côte d’Ivoire and ways to prevent those from materializing by “seeing like youth” (King et al. Reference King, Harel, Burde, Hill and Grinsted2020; Manful Reference Manful2022). We argued in this respect that youths’ experiences during the peacebuilding process and their perceptions of that process and its achievements determine to a large extent whether or not youths might think of violence as their only “bargaining chip” in the near or more long-term future. Commonly characterized either as “idealists” or “criminal opportunists” (Murphy Reference Murphy2003), we emphasized that the identities of post-conflict youths are dynamic in practice and their political involvement contingent on the structure, opportunities, and precarity of the post-conflict environment (Berckmoes Reference Berckmoes2014; McMullin Reference McMullin2022; Olawale & ‘Funwi Reference Olawale and ’Funmi2021). For this reason, we examined the peace perceptions of a large and heterogenous group of young men and women, instead of focusing on (formerly) mobilized youths only, as is the general tendency in youth-focused conflict scholarship.

Analyzing 905 essays written by secondary-educated adolescents in the cities of Abidjan and Bouaké, we found that these youths were generally optimistic about the peace dividend. According to a majority of participants, Côte d’Ivoire was stable at the time of our research. More convincingly, more than 70 percent of students believed that the country would remain peaceful after the 2020 elections. Comparative survey research showed that such optimism was more moderate among the adult population (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017; ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015). This reflects findings from other survey-based research in Africa and beyond which show that younger people are generally somewhat more positive regarding their futures (Resnick Reference Resnick, Mueller and Thurlow2019). With older students being marginally more pessimistic than their younger peers, we even noticed such dynamics within our own sample. According to Danielle Resnick (Reference Resnick, Mueller and Thurlow2019), such changes reflect adolescents’ increased awareness of the political environment once they reach or pass the voting age.

Our fine-grained analysis of students’ statements and descriptions showed that this general optimism came with a number of important caveats, however. Descriptions of the political climate as a “cold war” or, in contrast, “cold peace,” as well as metaphors of the country being “on one leg” or resembling a “sleeping volcano” are telling in this respect. In many ways, these words echo those of Jessica Moody, who wrote that Ivoirian citizens perceive a “façade of peace that has been established, while reconciliation and reintegration remain unfinished” (Reference Moody2021:116). First, even though a majority of young women and men described the country as stable, at least one third of the students worried about insecurity, lack of socioeconomic opportunities, and persistent division, which are examples of, common “push” factors behind young people’s choice to join armed groups. Second, those who experienced the country as peaceful often shared reservations too, similar in nature to those who perceived the country to be unstable. Notably, ethno-religious and political grievances were particularly strong among adolescents belonging to the ethno-religious group of former president Laurent Gbagbo. In their essays, many students lamented ethnic favoritism and at times reproduced Gbagbo’s nativist and anti-colonial discourse. More generally, there was a significant association between youths’ views on current and future peace prospects and their ethnic and religious group belonging, even though it was not strong. Interestingly, this identity effect interacted with place belonging. Christian students in Bouaké, for instance, were more positive with respect to the 2017 sociopolitical climate and future peace than those in Abidjan—a silver lining in the sense that ethno-religious identity seems not to be the all-determining factor that it is usually presumed to be.

To improve post-conflict stability and address the constraints young people face, finally, we asked students to formulate interventions aimed at fostering and/or consolidating peace. Five themes emerged: First, most proposed peacebuilding strategies focused on building social cohesion. This echoes past and ongoing peacebuilding activities in the country, that, in line with the local turn in peacebuilding, focus on grassroots reconciliation. Many of the country’s challenges remain to be addressed at the national level, however (Piccolino Reference Piccolino2019), which the students recognized as well. As such, second, they formulated strategies that focused on elite-level reconciliation. Importantly, many accounts in this category called upon leaders to cooperate and concede their electoral loss. More generally, the essays uncovered a malaise among youths regarding elections in their country. Similarly, the OECD (2017) survey established that trust was low among youths with respect to the electoral process. Clearly, there is a need to reestablish confidence in this respect. Third, besides local and national reconciliation, other peacebuilding strategies that students proposed focused on improving security in the country, and, fourth, ensuring socioeconomic opportunities for all. Such suggestions are in line with youths’ demands in other post-conflict societies, including Kenya (King Reference King2018). Fifth and last, taking stock of the reproduction of yesteryear’s gerontocratic order, it is surprising that only a small number of students explicitly called for handing over power to younger generations and creating avenues for political participation. More generally, however, engagement in the democratic process is low among younger Africans, especially in contexts of the entrenchment of incumbent leaders as is currently the case in Côte d’Ivoire (Resnick & Casale Reference Resnick and Casale2014).

All in all, the student essays indicate that, while peace had to some extent been consolidated by 2017, youths in Côte d’Ivoire had been remarginalized in that process and continued to face many constraints. Those constraints were not unique to them, however. Existing survey data showed striking similarities between this group and the general adult population (Afrobarometer Round 7 2017; ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015). These similarities, we argue, need to be understood in the societal context of Côte d’Ivoire, and other African societies for that matter, to the extent that youthhood, irrespective of age criteria, is increasingly prolonged or blocked altogether (Honwana Reference Honwana, Foeken, Dietz, de Haan and Johnson2014). We nonetheless believe that the results of this study show that comprehensive youth-targeted efforts are needed to overcome the feelings of “stuckness” prevalent among the group of secondary-educated youths in particular. Not only does survey data indicate that relatively educated Ivoirians (having at least secondary education) generally feel more discriminated against than others (ENV survey; Tape et al. Reference Tape, Samassi, Touré, Yao, Abou and Amani2015; Afrobarometer Round 7 2017), educated youths across sub-Saharan Africa also tend to protest more than their peers with lower levels of education, in particular when they are also unemployed, have little trust in political institutions, and experience higher levels of deprivation (Resnick Reference Resnick, Mueller and Thurlow2019). While we agree with Banégas and Popineau (Reference Banégas and Popineau2021) that “it is not at all sure that the new generations (…) left behind by ‘emergence’ have the means to overthrow this gerontocratic order,” the continued presence of exactly these push factors in Côte d’Ivoire call for action.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our earnest gratitude to the students who participated in our research for sharing their perspectives on the peacebuilding process in Cote d’Ivoire. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor of ASR for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Their suggestions have significantly strengthened our article.