As twentieth-century Americans gained access to new federal government benefits, generous policies grew popular with citizens, who in turn mobilized to protect them, making them politically sustainable (e.g., Lubell Reference Lubell1952; Pierson Reference Pierson1994). Although Social Security, for instance, faced initial opposition from Republican elected officials and conservative elites, its beneficiaries eventually became a formidable political force that effectively pressured lawmakers of both parties to safeguard the program (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a). Yet in the twenty-first century, partisan polarization creates a new political context that may interrupt the familiar process in which program popularity grows as individuals receive benefits. Instead of party leaders converging to embrace new programs, they diverge to rally their respective bases of political support, with opponents threatening to terminate policies enacted by their partisan foes. These circumstances introduce a new, not well explored dynamic that may influence beneficiaries, including partisans, shaping their response to programs.

This raises a pair of questions: first, how do political conditions affect whether public support develops for a new policy? Second, and more specifically, does the presence of partisan polarization prevent the emergence of support? The answers to these questions are crucial to understanding whether policies, once enacted, can endure. Drawing from the broad literature on partisan politics and political behavior, we propose an integrated theoretical framework that considers policy feedback in the context of policy change threat and polarization. We examine how it may be affected by two sources of variation: first, the extent of partisan polarization in the mass public and, second, the presence or absence of policy change threat (hereafter, referred to as “policy threat”) in which an existing policy faces possible repeal or fundamental weakening.

Our investigation builds on policy feedback theory, the idea that policies, once adapted, reshape how citizens experience government programs or regulations and that, in turn, affects their political attitudes or participation. Feedback effects are typically thought to emanate from endogenous features of policy design (Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). These may include “resource effects,” channeled through the money, goods, or services they offer, as well as “interpretive effects,” sent through the messages or lessons they convey (e.g., Cook, Jacobs, and Kim Reference Cook, Jacobs and Kim2010; Rose Reference Rose2018; Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Soss Reference Soss1999). Yet scholars have tended to treat policies as though they yield consistent outcomes, irrespective of exogenous political circumstances (but cf. Béland, Campbell, and Weaver Reference Béland, Campbell and Weaver2022; Pacheco, Haselswerdt, and Michener Reference Pacheco, Haselswerdt and Michener2020; Pacheco and Maltby Reference Pacheco and Maltby2019). The result is that policy feedback analysis has yet to give systematic attention to how variation in political conditions influences whether feedback effects actually emerge, and if so, when (Patashnik Reference Patashnik2019).

We expand the policy feedback analytical framework by incorporating mass partisanship, given its exceptional influence on social identity and the mass public’s political choices (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Barber and Pope Reference Barber and Pope2018; Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). Major policies like Social Security and the GI Bill reshaped politics and policy in the middle of the twentieth century when partisanship was relatively muted. Since the 1990s, however, Americans have sorted ideologically between the parties, and partisanship has come to play a formidable role in politics, generating highly negative views of those in the other party (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2010; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009; Mason Reference Mason2018).

Partisan polarization creates a new political context for policy feedback. Recent research indicates that rising partisanship may weaken policy feedback (Béland, Rocco, and Waddan Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2018; Galvin and Thurston Reference Galvin and Thurston2017; Oberlander and Weaver Reference Oberlander and Weaver2015; Patashnik and Zelizer Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013, 1080). A few empirical studies, each focused on the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the sweeping health care reform law signed by President Barack Obama, find evidence that partisanship does dim feedback effects (e.g., McCabe Reference McCabe2016). Early on, beneficiaries credited the law with improving access to health insurance or medical care for themselves and their families, but their overall assessment of it depended on their partisan identity and trust in government and not on their policy experiences (Jacobs and Mettler Reference Jacobs and Mettler2018, 356). Strong partisanship also deterred Republicans from enrolling in ACA-provided insurance plans (Lerman, Sadin, and Trachtman Reference Lerman, Meredith L. and Samuel2017). One innovative panel study did find that some ACA experiences during 2013–2014 led to more positive views of the law among those enrolled in marketplace insurance plans regardless of partisan identity (Hosek Reference Hosek2019). But each of these studies focused on the first several years of the law’s implementation, before the political threat to its future became viable. Scholars have yet to consider how policy feedback is affected when a policy faces an existential threat at the same time as heightened mass partisanship roils the polity.

Threats to repeal or substantially weaken major new policies influence how citizens respond to them. A rich psychological literature details how humans, faced with an immediate threat to resources crucial to their survival, behave differently than normal, and political scientists have argued that this occurs in politics as well. When the Reagan administration threatened Social Security benefits in the 1980s, it powerfully heightened policy feedback effects, causing a spike in participation rates among seniors, who mobilized to protect the program (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a, 106–13; Pierson Reference Pierson1994). Yet those developments unfolded in a period marked by low partisan polarization, leaving open the question of how policy threat will affect feedback in the context of strong partisanship.

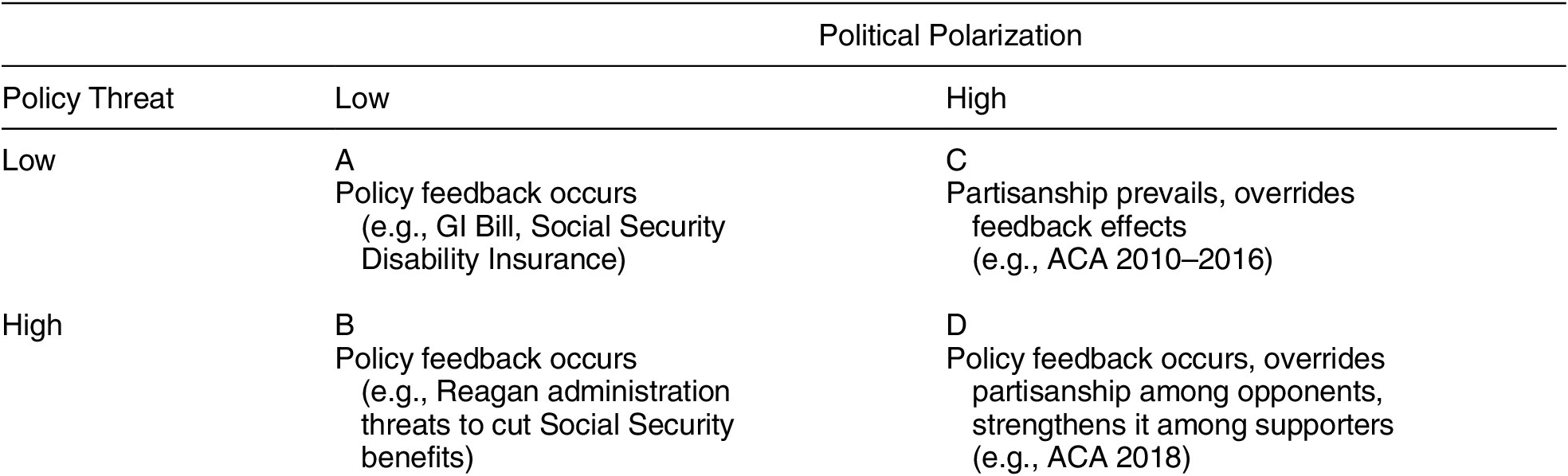

Our overarching argument is that policy feedback effects are conditioned by the existence or absence of both strong mass partisanship and policy threat. In the absence of either, policy feedback effects may be explained solely by policy design and individual attributes of beneficiaries, as demonstrated by the GI Bill and Social Security Disability Insurance (Mettler Reference Mettler2005; Soss Reference Soss1999). The presence of policy threat in the absence of strong partisanship may strengthen feedback effects, as Pierson (Reference Pierson1994) and Campbell (Reference Campbell2003a) demonstrated with respect to Social Security in the 1980s. Conversely, elevated partisanship in the absence of policy threat may reinforce partisanship and effectively block or weaken feedback effects, as several studies find to have been the case for the ACA in its early years (though for an exception, see Hosek Reference Hosek2019).

What occurs when both polarization and threat occur simultaneously? We develop a theory that predicts that under these circumstances, policy feedback effects will be accentuated. We highlight two mechanisms: salience, as threat induces people to notice or appreciate policies more than they had previously, and loss aversion, as the prospect of losing benefits evokes a stronger reaction from people than did gaining them in the first place. We expect that in the case of a policy that provides for basic needs, these dynamics may be sufficient to blunt the powerful influence of mass partisanship and permit policy feedback effects.

We test this theoretical model of policy feedback by focusing on the ACA. We probe how Americans responded to it initially and how their responses were affected once an empowered political opposition put its future in doubt. The ACA was enacted in a deeply polarized Congress and its early years of implementation were plagued by partisan attacks and Republican calls for its repeal, resulting in over 50 House votes for its termination. Once Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House after the 2016 elections, the threat became real: they stood poised to abolish the law, and if they fell short of that, to weaken it. The House of Representatives again voted for its repeal, and this time the Senate came within one vote of eviscerating critical parts of it. Although outright repeal failed, Congress succeeded in terminating the ACA’s individual mandate provision and the Trump administration continued to attack the law using its administrative powers and by supporting numerous court challenges to it. Therefore, the ACA provides an excellent case for examining whether the GOP policy threat to terminate or weaken the law triggered partisan responses to it, limiting feedback effects, or instead heightened feedback effects and broadened support for it.

Our five-wave national panel study of the ACA from its enactment in 2010 through 2018 equips us to study the longitudinal dynamics of public attitudes in the midst of strong partisanship, and the effect of policy threat once Republican elected officials stood poised to decimate the policy. We find that the GOP raised the salience of the ACA’s benefits, grabbing the attention of low-income individuals and those who had not previously perceived its effect, and strengthened their support for the law. In addition, the repeal threat affected individuals’ voting calculations in ways not intended by its GOP supporters: it mobilized Democrats to vote based on their concerns about “the health care issue” and muted such behavior among Republicans. These results suggest that policy threat introduces important contingencies in policy feedback, heightening its effects for some populations while depressing it for others, and mitigating partisan polarization in some cases. This finding points to the ACA’s substantial impact and the importance of the political context in conditioning policy feedback effects. In the next section we examine prior research on policy feedback and political threat before moving on to discuss our panel data and the results of our analysis.

How Political Conditions Influence Policy Feedback

Incorporating Policy Threat into Policy Feedback Research

“Policy change threat” is an established concept, defined by Joanne Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Krosnick, Holbrook, Tahk, Dionne, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016, 175) as “a citizen’s perception that a politically powerful individual or individuals are mobilizing to change public policy in a way that the citizen opposes.” In research conducted before Republicans gained control in 2016, these scholars anticipated that perceptions of such threat emerge when “a newly elected President … express[es] a commitment to changing an existing law or passing a new one” (175). In our analysis, policy threat refers to the political conditions that exist when the opponents of a policy, who have targeted it for repeal or weakening, gain control of law-making institutions and thus wield the power to attempt to carry through on those plans.

Scholars have offered two explanations for the influence of policy threat on political attitudes and behavior. The first, the salience explanation, emanates from social psychologists who draw on Darwinian evolutionary theory and observe that any organism, in order to survive, must seek out food and avoid predators; when the human brain detects a threat, it triggers humans to “stop what they are doing, reevaluate their current situations, and determine new courses of action” (Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2004, 509). Political scientists who study interest groups find that threatening circumstances, especially policy-change threats, modify people’s “information, preferences, and resources,” and these in turn “interact with the actual incentives that organizations offer, forming the subjective assessments of benefits and costs that enter into personal calculations” (Hansen Reference Hansen1985, 80). As a result, threats can make organizational benefits become more salient, more noticeable, and more important to people (Walker Reference Walker1991, 28, 43, 47).

The second explanation for policy threat comes from research by behavioral economists on dynamics related to the asymmetry of losses and gains, specifically the concept of loss aversion. Kahneman and Tversky (Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984) demonstrate that individuals, under certain circumstances, are particularly sensitive to loss and, indeed, may place a higher weight on avoiding loss than securing gain, even if the loss and the benefit are of equivalent value. Accordingly, a threat by politicians to reduce or terminate benefits could be expected to generate a pronounced negative reaction, even among those who had not expressed appreciation of benefits previously. Paul Pierson (Reference Pierson1994) found that efforts at retrenchment in both the United States during the Reagan administration and Great Britain under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher were “extremely treacherous” because of voters’ “negativity bias,” meaning that they are more responsive to losses than gains. “The concentrated beneficiary groups are more likely to be cognizant of the change, are easier to mobilize, and because they are experiencing losses rather than gains will be more likely to consider the change in their voting calculations” (Pierson Reference Pierson1994, 18). Similarly, Campbell showed that the Reagan administration’s efforts to curtail Social Security benefits heightened seniors’ awareness of risk and motivated them to “ignore the rational calculations of the Olsonian free rider and instead work to defend their programs” (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a, 101).

Building on these ideas, we argue that policy threat may heighten policy feedback effects, even amid strong mass partisanship. Among those likely to be policy opponents or unengaged, policy threat may increase the salience of public policies by making individuals more attentive to policy benefits than they had been previously and thus more inclined to support them. Although the basic model of policy feedback predicts that effects will occur exclusively among individuals who are most directly affected by policy resources or messages, policy threat may broaden the scope of effects to additional individuals. For example, feedback dynamics may also encompass beneficiaries who perceived a lesser effect of the policy on their lives (e.g., they may already have been insured prior to the ACA’s enactment but gained new protection against losing insurance owing to the restrictions the law placed on companies), family members or community members of beneficiaries, people who are relatively unaffected by the policy personally but nonetheless appreciate its effect on others, and those who appreciate the peace of mind of having future access to benefits “just in case” they or their family need them. Policy threat may also lead to an elevated sense of loss aversion, activating beneficiaries who are less politically engaged and who had exhibited less concern about the policy until faced by the prospect of its demise. In either case, policy threat may grab individuals’ attention and trigger a powerful focusing moment that evokes their policy support (Cho, Gimpel, and Wu Reference Cho, Gimpel and Wu2006). Meanwhile, for policy supporters, the combination of polarization plus threat may strengthen feedback effects.

How Do Policy Feedback Effects Vary with Policy Threat and Partisan Polarization?

Table 1 summarizes key theoretical expectations of policy feedback effects under four possible combinations of policy threat and partisan polarization.Footnote 1 In the absence of either condition, policy feedback effects are likely to occur in ways predicted by theories that emphasize the role of policy design, as indicated in quadrant A. This is evidenced by a number of studies of policy feedback that focused on periods prior to 2000, featuring lower levels of partisan polarization. Examples include the GI Bill’s education and training benefits, which prompted beneficiaries to become more engaged in politics, and Social Security Disability Insurance, which conveyed salutary messages to beneficiaries, bolstering their political efficacy (Mettler Reference Mettler2005; Soss Reference Soss1999). Quadrant B combines high policy threat with comparatively mild partisan polarization, producing policy feedback. This is exemplified by the Reagan administration’s announcement of a plan to cut benefits for early retirees, tighten disability requirements, delay benefit increases, and reduce benefit growth, which triggered a backlash that strengthened support for the program (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a, 90, 103–11).

Table 1. The Potential Influence of Policy Threat and Polarization on Policy Feedback

High levels of partisan polarization in contemporary American politics, by contrast, can override policy feedback when it occurs in the absence of policy threat. Under these circumstances, scholars of political polarization would expect individuals to sort into partisan and ideological clusters and cleave more firmly to the issue positions of their respective leaders when new policies are introduced (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2010; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009). This expectation is represented by quadrant C in Table 1. The early implementation of the ACA, from 2010 to 2014, featured the roll-out of several policies that Americans valued including the coverage of young adults on their parents’ coverage to age 26, expanded prescription drug coverage for seniors, and new coverage rules applied to insurance companies, followed by the exchange subsidies and expanded Medicaid. Yet several prior studies of the ACA suggest that these years were marked by sharp partisan divergence in Americans’ overall assessments of the law, as Democrats grew increasingly supportive and Republicans more opposed (e.g., McCabe Reference McCabe2016; Oberlander Reference Oberlander2020). In an era of strong partisanship among national and state lawmakers, stances on key policies are highly aligned with partisanship, becoming a litmus test for partisan identification.

However, when change in political control poses a serious threat to an existing policy we expect policy feedback to prevail even in the presence of high levels of partisanship. This set of circumstances, captured in quadrant D in Table 1, is illustrated by the dynamics associated with the actions of Republican politicians to repeal the ACA when they took control of Congress and the White House in the 2016 elections. The real threat to regulations and medical services vital to human life may have elevated the salience of benefits and triggered loss aversion sufficiently to offset the powerful allure of partisan identity, thus prompting some Americans who usually support Republican Party positions to become more supportive of (or less adamantly opposed to) the ACA. In other words, we expect threat to mitigate the strong partisanship of opponents, permitting policy feedback to occur among Republicans, and for it to accentuate the already-strong support of Democrats.

Our research into how political conditions shape policy feedback effects has two distinctive features. First, we focus on political attitudes. A large literature examines how the ACA or other health care policies have affected the political participation of the mass public (e.g., Baicker and Finkelstein Reference Baicker and Finkelstein2019; Clinton and Sances Reference Clinton and Sances2018; Haselswerdt Reference Haselswerdt2017; Haselswerdt and Michener Reference Haselswerdt and Michener2019; Michener Reference Michener2018). In contrast, fewer studies examine the effect of the ACA on political attitudes—namely, policy support (e.g., Hopkins and Parish Reference Hopkins and Parish2019; Hosek Reference Hosek2019). For example, Katherine McCabe (Reference McCabe2016) shows that those who experienced a positive change in their insurance situation adopted a more positive view of the ACA, but partisan bias prompted Democrats to be more likely to credit the law for such changes, whereas Republicans were more likely to blame it for negative changes in their insurance situation. However, these studies examine the ACA during early implementation, prior to the 2017–2018 escalation of policy change threat (but cf. Lerman and Trachtman Reference Lerman and Trachtman2020, which draws on 2017 data). Our analysis of threat builds on these studies as well as earlier policy feedback research that considered the effect of threat on political participation (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a; Reference Campbell2003b; Cho, Gimpel, and Wu Reference Cho, Gimpel and Wu2006). We draw on these latter studies of political participation to examine the influence of threat on political attitudes—namely, policy support.

Second, although most studies of the ACA examine how just one of its features—such as expanded Medicaid or health exchanges—affects individuals who benefit directly, we take a broader approach, encompassing both the entire law and the United States population generally, beneficiaries and nonbeneficiaries of such provisions alike. The ACA is a broad, multifaceted law that includes not only redistributive features such as those mentioned above but also a wide array of regulatory changes, such as the requirements that insurance companies can neither avoid coverage of nor terminate benefits for those with preexisting health conditions or children. Nearly all Americans are affected by the ACA, most in several ways, and the particular features of the law that most affect individuals likely vary over the life course. Therefore, we are interested in how Americans respond to the law generally, not just to one component of it. In addition, we are interested in all Americans’ responses. This is consistent with new research that demonstrates that the self-interest assumptions underlying the typical approach to be inadequate: individuals are members of families, communities, and a nation, and they may have their views of policies affected by broader concerns that transcend their own personal well-being (Jacobs and Mettler Reference Jacobs and Mettler2018). Although policy feedback research to date has produced rich findings by focusing on how individuals in targeted groups of specific policies are affected, we give broader attention to how mass publics respond to laws.

Theoretical Expectations: When Threat Confronts the ACA

In summary, we have four sets of theoretical expectations about how the threat to terminate or weaken the ACA, in a context of high partisanship, would affect Americans’ political attitudes.

-

➢ We expect that the policy threat posed to the ACA during 2017–2018 heightened policy feedback effects by increasing both support for the ACA and motivation to prioritize the health care issue in selecting candidates.

-

➢ We expect that policy threat heightened the ACA’s salience among those likely to have been less attentive to it previously (including low-income people and those who discerned less of an effect on their access to health care) and generated feedback effects among them.

-

➢ We expect that policy threat triggered loss aversion toward the ACA among Americans generally, generating feedback effects.

-

➢ We expect policy threat to moderate partisanship by both depressing its effect among Republicans (producing increased ACA support and muting the motivation to make voting decisions based on health reform) and accentuating its influence on Democrats (further increasing ACA support and health-care-motivated voting).

Data and Methods

Panel Design

We use a panel study to analyze the longitudinal effects of policy feedback, with a focus on the effect of political threat. Panel data make it possible to track changes in individual attitudes and behavior, asking the same pool of respondents identical questions over time. This approach rigorously follows change at the individual level and permits direct estimates of how changes relate to policy experiences together with a comparison of years before and after (Bartels Reference Bartels1999). The panel study approach to examining the ACA’s effect on individual-level political attitudes and behavior corrects a methodological drawback of most prior policy feedback research—selection bias. Previous empirical studies of policy effects mostly consisted of in-depth case studies and comparisons across several policies. These studies relied primarily on cross-sectional data, making it difficult or impossible to determine whether observed attitudes and behavior actually result from the policy intervention or instead emanate from preexisting characteristics that are not known or cannot be controlled for in statistical analysis. A few recent studies use longitudinal rolling cross-section survey samples to test policy feedback effects on political participation (e.g., see Clinton and Sances Reference Clinton and Sances2018; Hopkins and Parish Reference Hopkins and Parish2019), but they mostly correlate changes in behavior with enacted policies at the state and county levels based on inferences from rolling survey samples. Only a few feedback studies to date have used panel data to track feedback effects at the individual level (Bruch, Ferree, and Soss Reference Bruch, Ferree and Soss2010; Hosek Reference Hosek2019; Morgan and Campbell Reference Morgan and Campbell2011, chap.7).

Our panel approach collected in-depth data from the same group of individuals soon after the passage of the ACA in 2010 and continued through the implementation of key provisions in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018. The first wave in fall 2010 surveyed 1,200 adults; this included 1,000 in a national random sample plus an oversample of 200 individuals who were between the ages of 18 and 64 and living in low-income households with incomes under $35,000. We returned to these same 1,200 individuals with the same questionnaire during four waves: in 2012, after the National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius Supreme Court decision; in 2014, one year after the health insurance exchanges began and 9 months following the start of the Medicaid expansions; in 2016, leading up to the presidential election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton; and in 2018, after President Trump and congressional Republicans pursued repeal and other steps to undermine the ACA. In each case, the interviews were conducted during the election season in September and October, when health reform received heightened attention. The 2010 survey used landlines only; the subsequent four waves used both mobile phone numbers and landlines to contact participants.

We retained subjects over time through regular communications and incentives.Footnote 2 The maximum total number of cases included in our analysis for this paper is 2,544, pooling participants across the five survey waves, each of whom participated in at least two waves. Overall, 66% (949 out of 1,473) of panelists from prior waves sampled completed the Wave 5 interview. Forty-four percent of the original 2010 survey (524 individuals) responded to all five waves, and 58% (691 individuals) participated in both 2010 and 2018.Footnote 3

Using the same survey instrument with a stable panel over time diminishes the risk that respondents’ answers are simply a by-product of how a question is framed. While responses to survey instruments at one point in time may be influenced by question wording, changes in responses over time to identically worded questions by the same individuals are more apt to reflect genuine reactions to new experiences.

Measures and Variables

We developed dependent and independent variables for our theoretical expectations. Our models focus on explaining the favorability of the ACA and the importance that individuals place on health care in making their voting decisions.

What We Are Explaining

We use two dependent variables. The first dependent variable, which examines the public’s overall evaluation of the health reform law, is comparable to the ACA favorability measures used in a few recent studies (Hopkins and Parish Reference Hopkins and Parish2019; McCabe Reference McCabe2016). Our measure is based on respondents’ evaluations of a “major health reform bill enacted in 2010” on a nine-point favorability scale from strongly unfavorable to strongly favorable.Footnote 4 Our second dependent variable involves Americans’ own assessment of their political motivation in voting and, specifically, the importance of health care in their evaluation of candidates. This variable is measured as a five-point scale from “not at all important” to “extremely important.”Footnote 5 To be clear, this variable measures an individual’s evaluation of the weight assigned to a policy issue in vote choice; panel data equips us to track variations in the weightings of individuals.

Explanatory Variables

We included four theoretically important independent variables to account for public assessments of the ACA and the importance of the health care issue to candidate evaluation. The first is the respondents’ reports on the ACA’s effect on “access to health insurance and medical care supported or provided by government” for themselves and their families. There are five response categories: “no impact,” “a little impact,” “some impact,” “quite a bit of impact,” and “a great deal of impact.” This variable measures individual assessments of a fundamental purpose of the ACA.

The second is annual income which is measured as a dichotomous variable: under $35,000 (scored as 1) and over $35,000. This variable measures the economic status of individuals who are potentially most affected by the ACA.

The third is partisan identity, which is measured along a seven-point scale: 1 for “strong Republican,” 4 for “independent,” and 7 for “strong Democrat.” The points in between indicate individuals who “lean” toward one of the parties or have a “weak” affiliation. This variable captures the defining political identity in contemporary American politics.

The fourth variable is the policy threat, which is measured with a dichotomous variable for the year 2018, as a proxy measure of the political circumstances that endangered the ACA’s future after the Republicans took control of law-making.Footnote 6 We then use “Year 2018” to create individual interaction terms with each of the three previous independent variables to investigate the potential divergent effects of the Republican repeal efforts based on individuals’ income, partisan identity, and experience with the ACA.

In addition, we included control variables to account for potential confounding relationships. In particular, we included measures of gender (coded as “1” for female and “0” for male), race and ethnicity (nonwhite), respondents’ ages, education,Footnote 7 and political knowledge.Footnote 8

Methods

Our analysis of ACA favorability and health care importance in vote choice relies on Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ADL) modeling, which is appropriate for analyzing dynamic panel data (Ahn and Schmit Reference Ahn and Schmidt1995; Anderson and Hsiao Reference Anderson and Hsiao1982; De Boef and Keele Reference De Boef and Keele2008). This method and the estimation of dynamic panel data models allow us to include prior favorability or prior issue-based candidate selection (i.e., lagged dependent variables) as explanatory variables measured with a lagged dependent variable (Arellano and Carrasco Reference Arellano and Carrasco2003; Greene Reference Greene2003; Honoré and Kyriazidou Reference Honoré and Kyriazidou2000). Substantively, the ADL specification examines how our theoretically important variables influence change in people’s ACA favorability or the importance of health care policy to their candidate selection rather than their absolute level of favorability or issue importance when voting.

Our panel includes individuals from varying socioeconomic backgrounds and diverse political perspectives. These factors might introduce heteroskedasticity. To account for potential heterogeneity, we specify robust standard errors in each empirical model.Footnote 9

Analysis

The policy threat by Republicans after the 2016 election to repeal and weaken the ACA unleashed significant and distinct effects on Americans’ support for the law and on the importance they attached to using health care to select candidates.

The Effect of Policy Threat on ACA Favorability

When the Obama administration implemented the ACA, it shielded health reform from an early legislative threat of repeal or significant weakening. The Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the ACA’s constitutionality also blocked an initial judicial threat. During this period of comparatively low threat, the public’s favorability toward health reform was closely related to partisan identity. As we show below, the partisan split on the ACA continues, but it has been altered by the dynamics of threat.

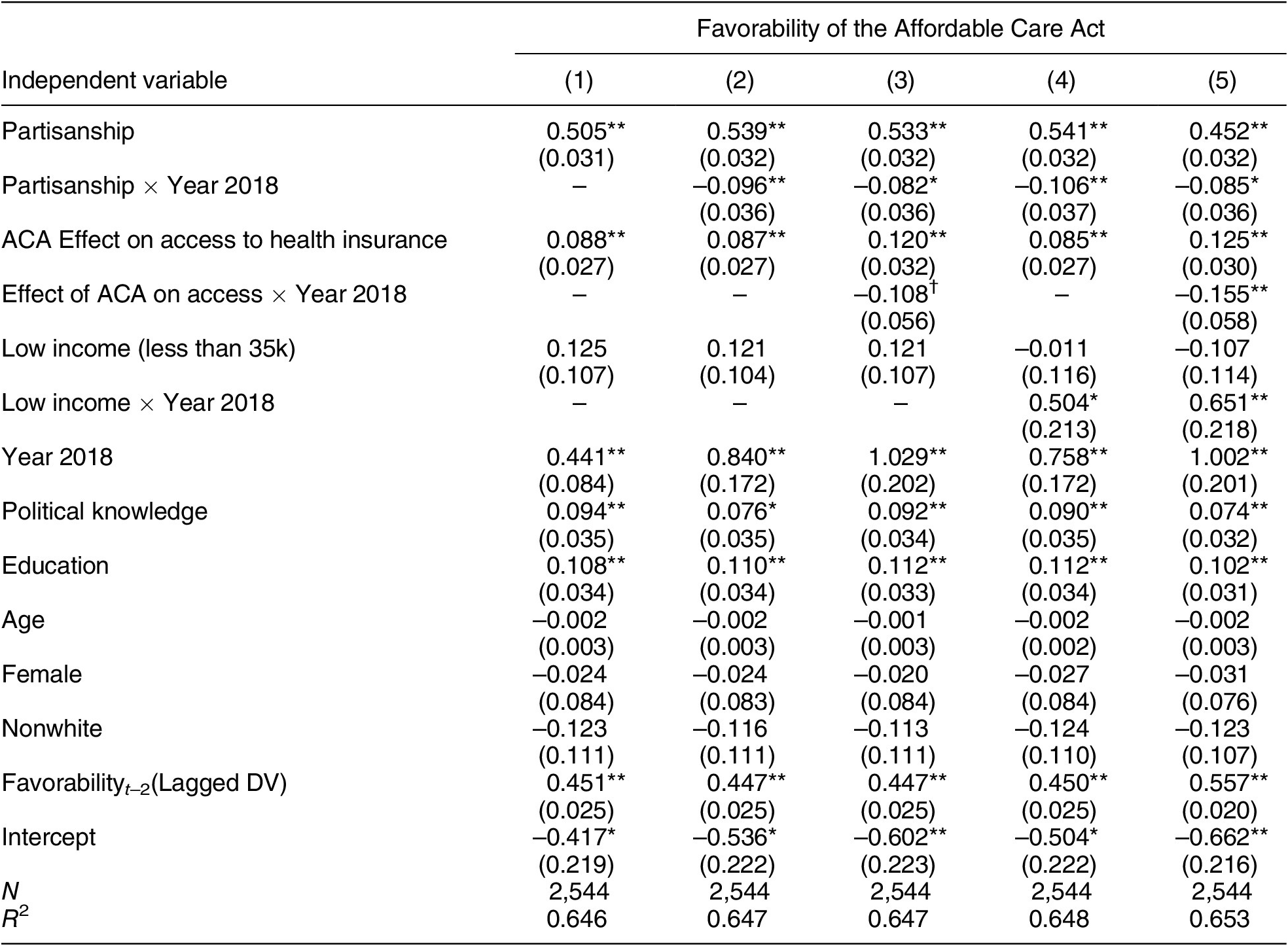

Table 2 presents three striking patterns about the influences of the policy threat on the policy’s favorability that were discernable by the fall of 2018. In each case, the patterns that ensued after the onset of policy threat contrasted to the established patterns beforehand. In the case of partisanship, for the first several years of ACA implementation, a familiar pattern became established: Democrats were significantly more supportive of the ACA than were Republicans. This partisan gap continued, as expected in quadrant C in Table 1. The potent and consistent influence of party identification on ACA support is apparent in the simplest model (Column 1, b = 0.505, p < 0.01) as well as the most specified model (Column 5, b = 0.452, p < 0.01).

Table 2. Political Threat, Policy Experience, and Favorability toward the Affordable Care Act: Linear Dynamic Panel Regression and Interaction Models

Note: The dependent variable “Favorability” measures respondents’ attitudes toward the 2010 health care bill, coded on a 1–9 scale, with “1” referring to “strongly unfavorable,” “5” referring to “neutral,” and “9” referring to “strongly favorable.” Models 1–4 are estimated using “xtreg” in Stata. Module (5) is estimated using “reg” in Stata. †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

However, as we anticipated the introduction of a potent policy threat after the 2016 elections changed the dynamics surrounding public reactions to the ACA. Once President Trump and Republican Members of Congress took actions to repeal and undermine the ACA, they inadvertently rallied support for it from an unexpected source—rank-and-file Republicans. The negative and statistically significant interaction of partisanship and “Year 2018” in Models 2–5 indicate that among Americans, Republicans became a source of the increased support for the ACA, as anticipated by quadrant D in Table 1. These findings contradict prior research that reported intense, unaltered partisan sorting in which Americans polarized into self-contained and stable blocs (e.g., Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2010; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009). Table 2 indicates that the policy threat to the ACA moderated the partisan split in ACA favorability that existed during the previous years.Footnote 10

The second finding in Table 2 is that the threat to the ACA’s future broadened appreciation of its direct effects on the lives of its beneficiaries. Individuals who reported the ACA’s strong effect on their own or their family’s access to health insurance and medical care were consistently more supportive of the law generally, well before 2017 and 2018, as is evident in Models 1 to 5. For instance, Model 1 shows that acknowledgement of the ACA’s personal effect on access to health care registers as a positive and significant effect (b = 0.088, p < 0.01) even after controlling for partisanship and a host of other potentially confounding factors. Yet policy threat jolted individuals who had not previously reported much of an effect of the ACA on their personal access to health coverage to become more favorable toward the law. In the fully specified Model 5, the interaction of access and Year 2018 yields a significant and negative coefficient (b = −0.155, p < 0.01); Model 3 indicates a significant negative coefficient (at the 0.10 level) for the interaction of ACA effect and Year 2018. This indicates that even those for whom ACA benefits had been relatively less salient previously now noticed and appreciated them more and became more favorable toward the law once it appeared to be vulnerable.

The third main finding pertains to how the effect of political threat is channeled by income to create asymmetric effects on low- and high-income people. Table 2, Column 1 reports an insignificant coefficient for the income variable. This finding suggests that prior to 2016 income alone is not a main driver of one’s view toward the ACA.

However, the interaction of low income and Year 2018 produces positive, significant coefficients in Models 4 and 5. The fully specified Model 5 in Table 2 shows that the interaction of being low income and Year 2018 exerts a potent effect (b = 0.651, p < 0.01). After Trump’s election, the political threat awakened low-income Americans, those who disproportionately stood to gain from the ACA since its passage in 2010 but had not previously fully appreciated the source of their new benefits.

Our findings that threat particularly triggered low-income individuals contrasts with Campbell’s analysis, which found that the 1981–1983 threats to Social Security activated low-income seniors nearly as much as high-income seniors. She regarded this as “notable” given that the former are less educated and less likely to belong to interest groups that mobilize seniors (Campbell Reference Campbell2003a, 111). In contrast, threat in the case of the ACA appears to disproportionately accentuate policy awareness among the less well-off.

In summary, Republicans’ efforts to repeal and weaken the ACA inadvertently accelerated its feedback effects. The threat fueled increased ACA support among several groups of individuals: Republicans, individuals who previously reported less of an effect of the ACA on their own and their families’ lives, and low-income people.

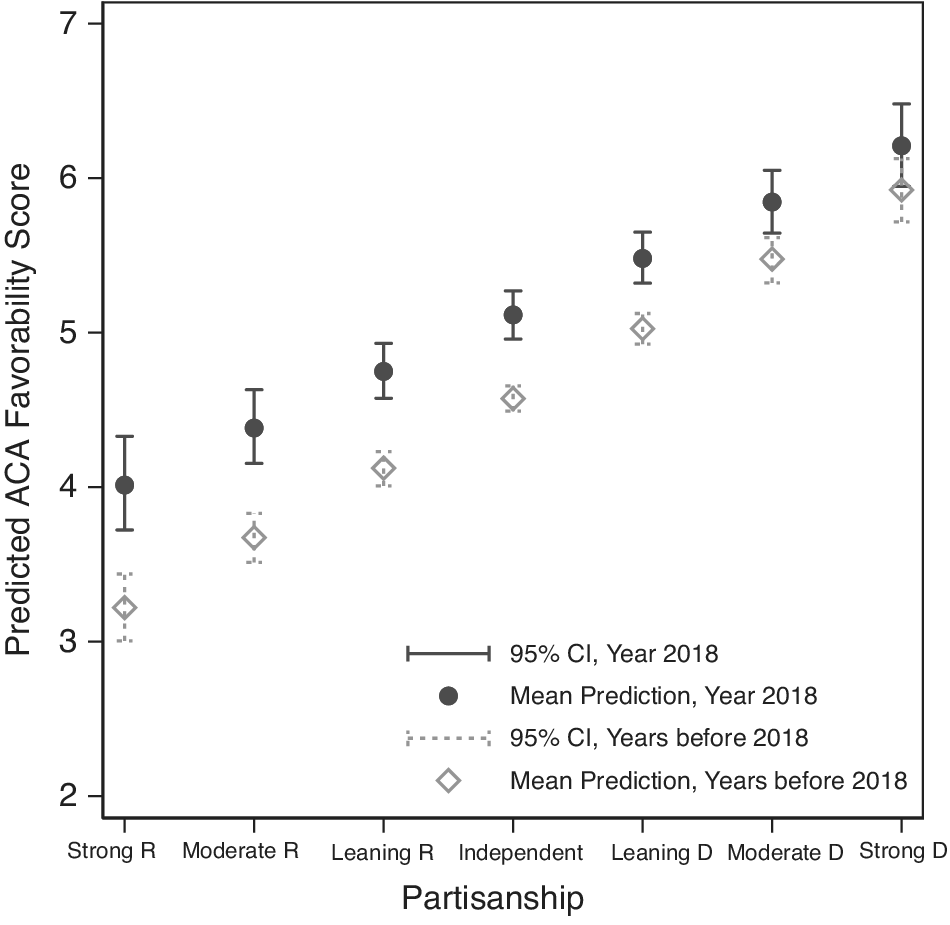

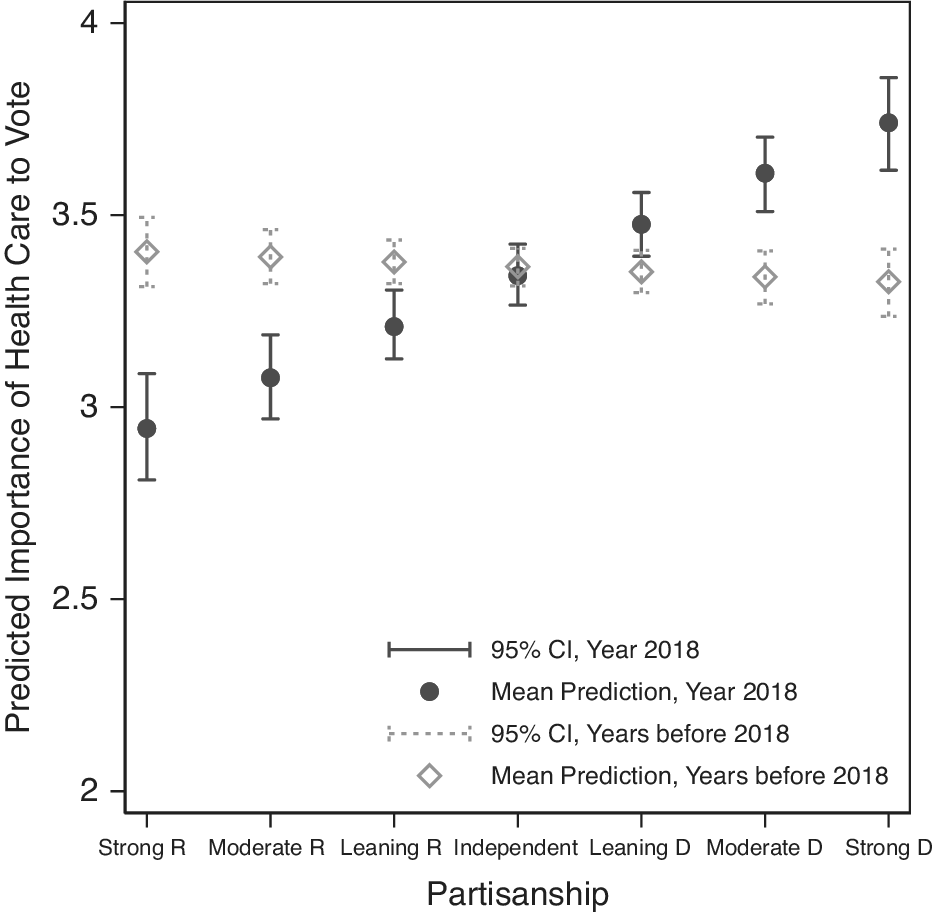

Figures 1–3 depict visually how the short-term effect of political threat on favorability is channeled through individuals’ partisanship, access to new ACA benefits, and their income. Based on the model in Column 5 in Table 2, we produce Figure 1 to show the dual effects of partisanship on favorability, conditioned by the year 2018. We rely on the Clarify (Tomz, Wittenberg, and King Reference Tomz, Wittenberg and King2003) routine in Stata 15, which uses the Monte Carlo simulations and out-sample predictions to show how the predicted favorability score varies across the full observed range of the party identification variable before and during 2018 (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000). The mean predicted favorability level and the 95% confidence intervals are calculated for the year 2018 and for the average across the prior four waves of our panel study from 2010 to 2016. All other explanatory variables are held constant at their means in this visual.

Figure 1. Political Threat, Partisanship, and Favorability toward the ACA

Note: Based on Table 2, Model 5.

The substantive finding of Figure 1 is twofold. On the one hand, Democrats are consistently more favorable toward the ACA than are Republicans. The average predicted favorability score for those who strongly identify with the Democratic Party is about 6 (out of a 1–9 Likert-type scale), but favorability scores were estimated to be much lower for strong Republicans (around 3 before 2018 and 4 during 2018). This partisan pattern originated during the ACA’s passage and implementation during 2010–2016 when the threat to health reform was comparatively low. On the other hand, though, Republicans are the source of the biggest gains in favorability under circumstances of threat: this is evident in the wider gap for Republicans than Democrats between the mean prediction for favorability in 2018 and the mean prediction for the 2010–2016 waves. Across the partisan identification scale, even those who have the least favorable evaluation (strong Republicans) increased their favorability score in 2018.

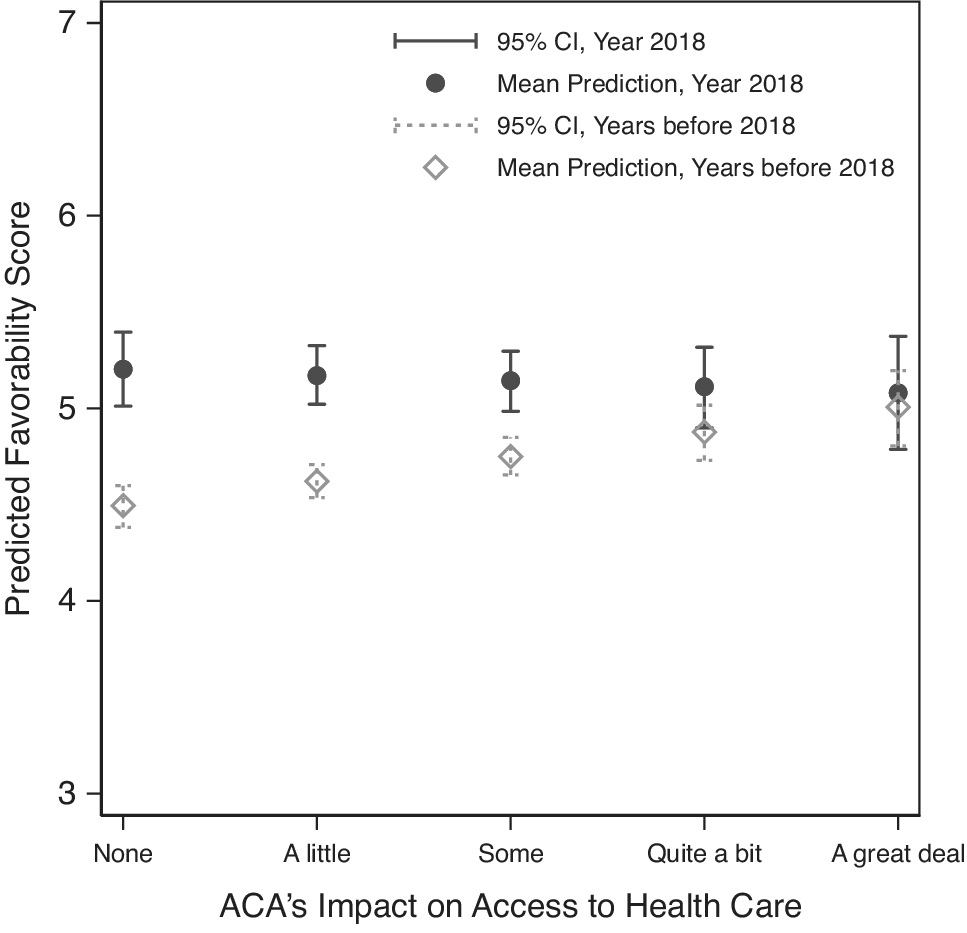

Figure 2 visualizes differential mean predicted favorability scores between 2018 and the prior 4 waves across the scale measuring individuals’ different experiences with the ACA. The greatest increase in favorability in 2018 comes from respondents who had not recognized any effect from the ACA’s expansion of access to health coverage for themselves and their families and who previously reported more negative assessments of it. Strikingly, by 2018 support levels for the ACA among those who report that they do not benefit from it personally resemble those of respondents who benefit from it “a great deal.” The threat against the ACA awoke individuals who had not previously appreciated its benefits.

Figure 2. Political Threat, Policy Experience, and Favorability toward the ACA

Note: Based on Table 2, Model 5.

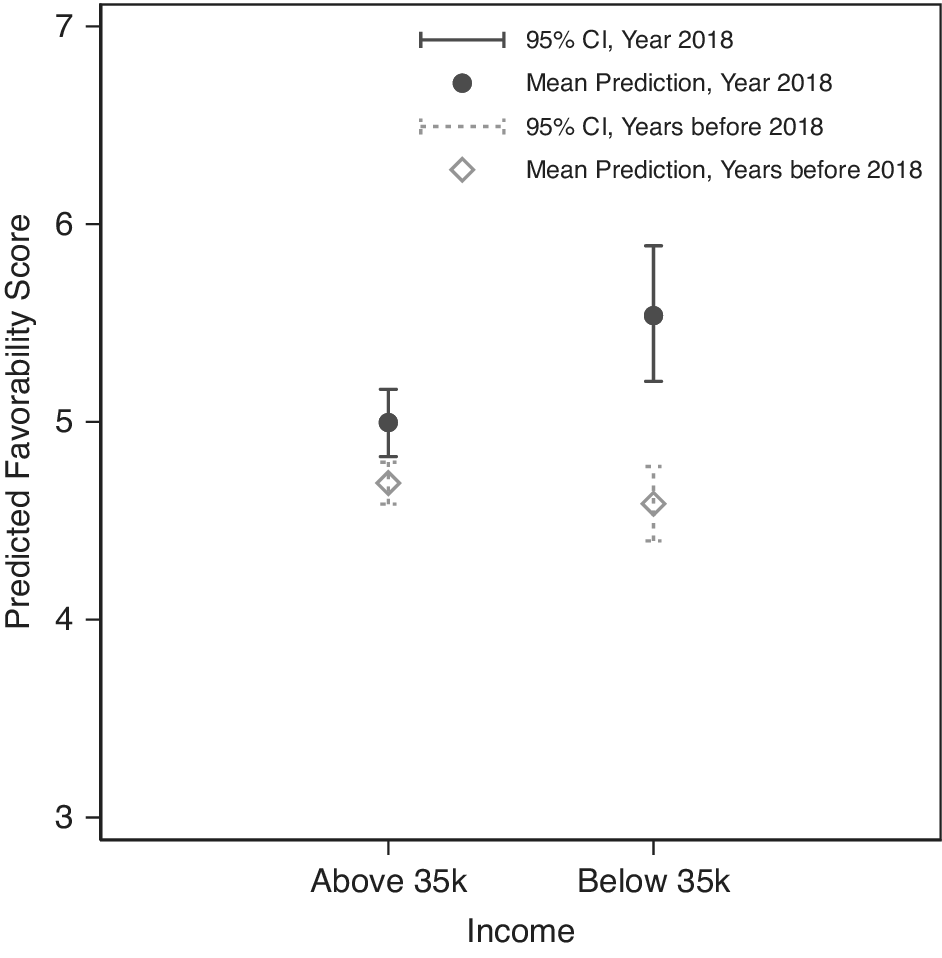

Figure 3 dramatically displays the sharp gains in support among low-income people after Republicans attempted to reduce or repeal the ACA. For individuals earning below $35,000 annually, there is a large gap between the mean predicted favorability in 2018 and before, whereas among higher-income individuals, favorability toward the ACA only increased slightly compared with years before 2018.

Figure 3. Political Threat, Income, and Favorability toward the ACA

Note: Based on Table 2, Model 5.

In summary, the repeal threat to the ACA during 2017–2018 significantly accelerated policy feedback effects, especially among groups of people who had not previously been responsive, including Republicans, those who did not discern an effect of the law on their personal access to health coverage, and low-income people. Unintentionally, the proponents of repeal and weakening the law broadened the ranks of its supporters.

Policy Threat and Issue-Based Voting Motivation

Now we turn to exploring whether threat might influence the importance that Americans reported they assigned to the health care issue as they decided which candidates to support in the 2018 election. This permits us to understand how people interpreted their own motivation in vote choice relative to how they did in previous years.

Up through the 2016 elections, before the threat to the ACA became a real danger, vocal opposition to the law among Republican officials in Washington motivated Republican citizens to assign importance to the health care issue when they selected candidates. Democrats were similarly motivated, in their case due to their support for the ACA. This is consistent with the pattern of partisanship and muted policy feedback identified in quadrant C in Table 1.

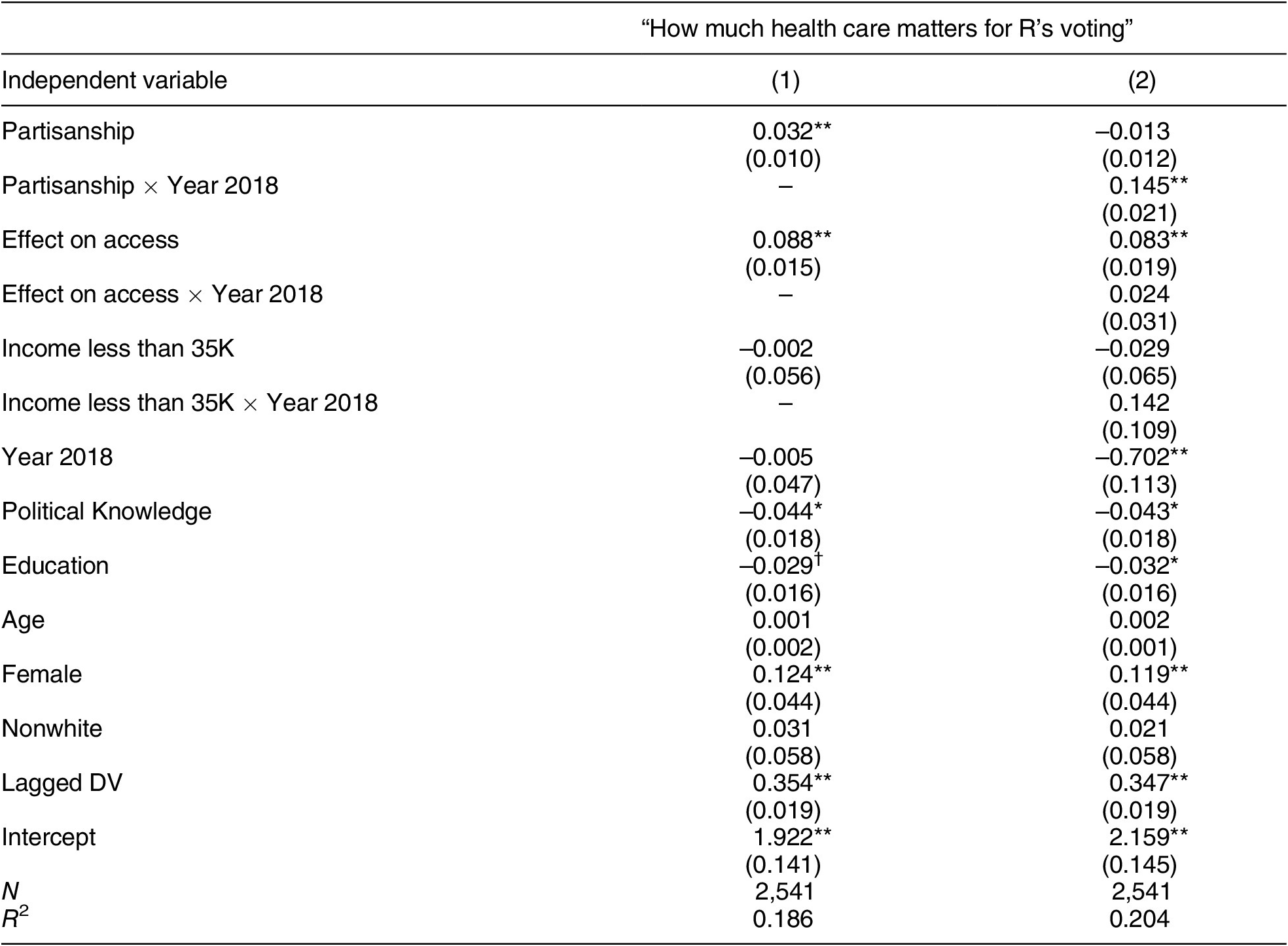

Our analysis of the effect of threat after the 2016 elections both confirms and modifies the predicted pattern of partisan sorting. Table 3 shows that partisanship increased the Democratic intent to make a vote based on the health care issue (Column 1, b = 0.032, p < 0.01). Our further analysis in Figure 4 reveals a striking seesaw pattern. For strong Democrats, the intent to cast a health care vote rose sharply from what it had been during the 2010–2016 period to an elevated level in 2018. In contrast, strong Republicans had been highly mobilized to vote in an anti-ACA manner during 2010–2016, but that changed in 2018, as the priority they placed on health care became muted.

Table 3. Political Threat, Policy Experience, and the Importance of Health Care for Voting

Note: The dependent variable measures how much health care matters for respondents’ voting. †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 4. Political Threat, Partisanship, and Importance of Health Care to Respondents’ Vote

Note: Based on Table 3, Model 2.

In earlier years, when Republican leaders criticized the ACA but were incapable of acting to repeal it, partisans did not vary much in the degree of importance they assigned to health care policy in influencing their vote choice, as indicated by the gray squares. The predicted importance of health care was quite close among “leaners” in both parties and not strikingly different even among strong partisans. Yet that pattern evaporated once the policy was actually under threat of termination. In effect, the strategy of President Trump and congressional majorities to use antagonism to the ACA to mobilize their base and demoralize Democrats backfired: it subdued Republicans, activated the allies of health reform, and rallied Democrats (Jacobs and Skocpol Reference Jacobs and Skocpol2015).

These findings modify our understanding of partisan sorting and policy feedback. Threat spurred both dynamics among Democrats, influencing them to make health policy a still-greater priority than they had previously. However, Republican voters under conditions of policy threat reacted in a manner that would not be anticipated by the scholarship on polarization: they scaled back their intent to vote based on health care.

Confirming the Effects of Threat and Policy Feedback

Increasingly sophisticated research by policy feedback scholars has used a range of empirical methods including causal modeling, experimental designs, and difference-in-difference estimation. To confirm our approach, we checked the robustness of our empirical findings from our ADL analyses using panel regression models without lagged dependent variables.Footnote 11 This alternative approach produced coefficients with consistent signs.

To investigate further the robustness of our analyses, we respecified our panel regression model using the fixed effects approach. In particular, we checked our regression results by including (1) fixed effects by respondents and (2) a full set of year fixed effects (i.e., year dummy variables) for our survey waves. The fixed effects approach produced similar substantive findings regarding the interplay between threat, partisanship, and individual’s experiences with the ACA; in general, the coefficients of our main variables continued to reach statistical significance and had consistent signs.Footnote 12

When Partisanship is Modified by Policy Feedbacks

Our analysis of the interplay of policy feedback and threat indicates that political attitudes and behavior are shaped not only by endogenous features of government programs alone but also by exogenous political conditions, modifying prior research on policy effects. Prior research indicates that in the absence of strong partisanship, policy design features combine with individual characteristics to shape policy feedback effects; even when policy threat occurs in such circumstances, it will likely heighten policy feedback effects. Conversely, when partisanship intensifies but threat is absent, polarization may overpower and nullify policy feedback effects, making policies vulnerable to repeal or weakening.

However, our findings suggest, that the influence of partisanship on public attitudes may be more conditional than appreciated previously (e.g., Bafumi and Shapiro Reference Bafumi and Shapiro2009). Our examination of the first eight years of the ACA’s implementation finds that the tangible threat to repeal it after the 2016 elections heightened its salience and triggered loss aversion, which led to policy feedback among Republicans. The influence of partisanship remained, but the threat of repeal prompted rank-and-file Republicans to become more receptive to policy effects and to resist party leaders’ efforts to rally opposition among them.

Evidence that policy threat can disrupt the hold of partisanship offers a specific and perhaps uncommon condition in which the power of this political identity is compromised. The ACA presented a distinctive set of circumstances that accentuated the effect of threat on feedback: a multifaceted policy that affects a central component of basic needs—health care—for Americans nationwide, and that became the focus of extraordinarily visible party conflict, carried out over a sustained period. The ACA’s far-reaching life-saving services likely made both less-engaged citizens and those whose own party leaders opposed it more attentive to and appreciative of its benefits and therefore more amenable to feedback effects even in a highly polarized environment. At the same time, the sustained political conflict the ACA precipitated—with party leaders keeping it in the headlines and prominent on the campaign trail for over a decade—spurred greater feedback effects among Democrats, particularly once it was under threat. In combination, these attributes elevated salience and loss aversion, triggering policy feedback.

Should we expect policy threat to offset partisanship in the case of additional policies? On the one hand, few policies are likely to engender the same combination of features that spur both policy threat and feedback. The most common policy threats are carried out by well-organized interests that quietly and successfully reverse taxes or regulations during the technical implementation process (such as the Dodd–Frank financial restrictions following the 2008 economic crisis); these occur without the broad public’s notice and in the absence of feedback effects (Jacobs and King Reference Jacobs and Desmond2021). Conversely, some highly visible policies, such as the pandemic-era stimulus bills, gain broad public support from the outset and do not become subject to threat. Even in today’s polarized polity, in fact, there continue to be bipartisan legislative enactments that are not stymied by the intense partisan threat that confronted the ACA (Curry and Lee Reference Curry and Lee2020). Partisan polarization does persist over policies such as immigration restrictions and gun control, but the fact that these do not affect the basic needs of most citizens mean that feedback effects are less likely to transpire (Barber and Pope Reference Barber and Pope2018, 42).

Yet on the other hand, policy feedback triggered by partisan threats may recur on occasion and yield vast consequences when it does. “Policy backlash,” defined by Eric Patashnik (Reference Patashnik2019, 48) as “a strong adverse reaction against a line of policy development,” has become more common in the contemporary political environment given its intense polarization and party leaders seeking opportunities to mobilize their bases. It presents “a particular threat today to the … sustainability of policies that serve diffuse, marginalized, or otherwise poorly organized constituencies” (Patashnik Reference Patashnik2019, 48). When partisanship and threat combine, it has the potential to prove fateful for existing public policies. Yet as we have seen, backlash may also eventually backfire, spurring both political advantages for partisan opponents and policy feedback effects that help make policies sustainable.

Moreover, American federalism adds still greater complexity to these dynamics when national policies that leave some authority to state governments. In the case of the ACA, decisions by state lawmakers in some instances heightened policy threat and in others mitigated partisanship, producing feedback effects (Pacheco and Maltby Reference Pacheco and Maltby2019; Pacheco, Haselswerdt, and Michener Reference Pacheco, Haselswerdt and Michener2020). The consequences of this interplay between the national and state level warrants greater attention.

Future analyses should investigate the mechanisms through which the public discerns a policy threat to be credible. It remains beyond our analysis here to probe how citizens distinguish between empty political threats (e.g., the numerous votes for repeal in the House when Obama still occupied the presidency and Democrats held the majority in the Senate) and those that can actually lead to policy termination. Scholars might consider the role played by the president as well as the media in making threats credible particularly in today’s polarized environment.

Although the breadth and circumstances of our findings remain to be specified, our analysis opens up new theoretical and empirical questions about the dynamics of policy feedback and the possibilities for policy sustainability in an age of pitched partisanship.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000612.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation that supports the findings of this study is openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FO6OXL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Joanne Miller and Robert Shapiro for crucial guidance at the outset of this project and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive advice on this article. We are also thankful to Mallory SoRelle, Deborah McFarlane, and participants at the 2019 Annual Meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association and American Political Science Association who provided useful feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award #69766. In addition, support was provided by Cornell University, including the Center for the Study of Inequality, the Department of Political Science; the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston; the Walter F. and Joan Mondale Endowment; and the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare that the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Cornell University, protocol ID# 1009001648. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s “Principles and Guidance on Human Subjects Research.”

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.