Soon after the April 1, 1964, military coup in Brazil, the generals who took power identified, imprisoned, and expelled thousands of members of the armed forces, across military branches. Those targeted had either opposed the coup or had been identified by these generals as subversive soldiers. The first groups to be expelled were “constitutionalist” officers, particularly those who supported ousted president João Goulart, and the sergeants and soldiers who had mobilized during the three preceding years to demand the expansion of their rights in the armed forces.

The political views and experiences of the expelled officers and the soldiers differed widely. While some were adherents of the communist ideology and looked to Cuba as a model for resistance in the context of the Cold War, others identified as constitutionalists and believed in a strong state that would control certain resources but also encourage private enterprise. They mostly shared a strong opposition to military interventionism and identified as “nationalists.” Nevertheless, they were often categorized as communists and treated as potential terrorists, purged from the armed forces and persecuted from 1964 until 1985. Prior to the coup, the Brazilian armed forces were already enforcing the punishment of soldiers accused of communist activity.Footnote 1 Between 1946 and 1964, approximately 1000 members of the armed forces endured political persecution. After 1964, however, arrests increased exponentially—between 1964 and 1985, more than 6500 officers and soldiers were expelled from the military ranks.Footnote 2 This spike in arrests highlights the efforts of the military government to cleanse the armed forces of opposition.

Throughout the twentieth century, military officers disagreed over the role of the armed forces in Brazilian society. While some believed the institution should refrain from engaging in politics and focus exclusively on external defense, others claimed the forces were obliged to intervene in political affairs when necessary.Footnote 3 Non-interventionist officers believed the armed forces should respond to democratically elected presidents. Interventionist officers, on the other hand, believed the armed forces were responsible for containing the spread of communism in Brazil.Footnote 4 Officers also disagreed about Brazil's role in the Cold War. While a group of “internationalists” believed in close alignment with the United States, others, who identified as “nationalists,” claimed Brazil should seek economic autonomy and control of its own resources.Footnote 5 These ideological divides inside the armed forces highlight the adverse environment in the institution during the period leading up to the coup. As interventionist generals took power in 1964, officers and soldiers who opposed the coup were expelled from the armed forces. Nevertheless, the ideological conflicts did not disappear after these expulsions.Footnote 6 After opponents of military intervention were expelled from the military, new conflicts took shape as former officers and soldiers continued to oppose military rule outside the military barracks.

The military junta that took power on April 1 and became the first military government of general Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, in office from 1964 to 1967, acted preemptively to avert reactions of members of the armed forces against the coup. Any indication that suggested a soldier or officer would challenge the coup, from participation in political activities such as rallies or protests to a private conversation about politics, was enough for the first military government to issue orders of expulsion.Footnote 7 Once expelled, many former military personnel stayed in Brazil and tried not to get involved in political activities during the era. Others, however, took an active role in opposing the dictatorship, and some even sought training from Cuba in guerrilla warfare. This article focuses on the cases of men who organized resistance movements against the government, from within Brazil or from exile. Using different tactics, hundreds of expelled officers and soldiers framed their opposition against the regime similarly. Stressing non-interventionism and economic autonomy in the context of the Cold War, these men conceptualized their opposition to military rule as a fight for national autonomy and democratic participation.

Historiography and Sources

The scholarship that examines the transformations within the armed forces after the 1964 coup and the experiences of officers who led military rule is extensive.Footnote 8 Many authors have studied military generals’ attempts to consolidate power as conflicts emerged between interventionist officers, who were themselves divided in two factions: hard-liners and moderates. Officers who believed in a long-term military intervention to end communist infiltration in Brazil were known as hard-liners, and officers who supported a short-term intervention and a relatively quick return of governmental control to civilians were known as moderates, or castelistas. This division of the military into just two categories has produced a binary view of history that opposes interventionist officers and civilian militants, whose numbers included labor unions and the student movement. Such interpretation is incomplete, neglecting deeper divisions within the armed forces, as many officers and soldiers disagreed with both the hard-liner and the moderate factions.

Some scholars have challenged the binary interpretation, showing deeper divisions within the armed forces during the dictatorship. Maud Chirio, for example, highlights the disagreements within the hard-liner faction, identifying what might be called two generations in this group. She claims that right-wing junior officers challenged hard-liner generals in their ideology and strategy between 1961 and 1978.Footnote 9 This group of junior officers fought to gain control of the core of the police state and enforced the state's clandestine actions inside the military barracks and in public spaces.Footnote 10 Other authors have written about the cases of leftist and constitutionalist (or simply non-interventionist) officers and soldiers, mainly during the years prior to 1964. These works have focused on conflicts such as the sergeants’ movement between 1961 and 1964, the revolt of the sailors in 1964, and the harassment of officers with ties to the Communist Party before 1964.Footnote 11 Such emphases have contributed to an understanding of political conflicts in the armed forces before 1964. They show how sergeants and sailors with leftist tendencies fought against a conservative and interventionist military ideology before the coup. However, after 1964, most officers and soldiers who disagreed with military interventionism either disappear from the historical record, or are examined individually or independently from their connection with the armed forces. That is the case of many soldiers who participated in the guerrilla movement between 1964 and 1975.Footnote 12

In the wake of the coup, just as the generals in power were creating institutions to eliminate resistance in unions and student movements, they also struggled to eradicate opposition inside the military. If we broaden the places and institutions in which we examine resistance and repression to include the armed forces themselves, we realize that the consolidation of military rule in Brazil was a more contentious process than what has been previously portrayed. Such focus shows that the armed forces were not a unified body that supported and enforced military rule. The officers who implemented the coup, took over the Brazilian government, and held onto it for over 20 years not only had to fight against leftist civilian movements in Brazil but also to struggle to transform the armed forces and eliminate any opposition that could emerge within the institution.

This article assesses how non-interventionist and nationalist officers and soldiers began to formulate different sets of tactics to challenge the newly installed regime. In particular, it examines the emergence and decline of two resistance movements, the Resistência Armada Nacionalista (RAN) and the Guerrilha do Caparaó. The analysis presented here relies on 30 interviews I conducted with expelled high-ranking officers, sergeants, and low-ranking soldiers; lawsuits filed by politically persecuted individuals and their families against the state in Rio Grande do Sul demanding financial reparations; intelligence reports that recently became available to the public at Brazil's National Archive; and documents from the São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro state archives. The interviews examined here attest to the personal and collective experiences of many members of the forces and show how invested many of them were in preventing the coup from taking place and fighting against the dictatorship once it had been established.Footnote 13 I have employed an analytical framework that interprets interviews through memory lenses. In this way, instead of inquiring if interviewees were being truthful when remembering certain events, I have attempted to understand how they constructed their narratives in a determined way. This study indicates that although expelled officers and soldiers disagreed on resistance tactics against the regime, they shared democratic and anti-interventionist ideals.

I am the first to assess and incorporate documents from the Air Force Intelligence Center (Centro de Informações da Aeronáutica, CISA) in a historical analysis focusing on expelled members of the armed forces.Footnote 14 This newly available set of sources allows me to expand on contributions other scholars have made about officers and soldiers who were expelled from the military from 1964 to 1985.Footnote 15 Nina Schneider has argued that the cases of expelled officers and soldiers have not been discussed at length because they challenge ideas of “perpetrators” and “victims” of the regime.Footnote 16 According to her analysis, scholars have chosen to focus on human rights abuses, often assuming that a nuanced representation of the military institution would be detrimental to condemning military rule.Footnote 17 In this article, I show that a nuanced focus on the armed forces, on the contrary, expands our understanding of military rule; it reveals that when coup leaders expelled non-interventionist members of the forces they failed to end internal conflicts present in the institution.

Instead of ending military ideological disputes, the generals who took power in 1964 brought about their expansion, as former non-interventionist officers and soldiers, together with civilians, began to fight against military intervention across the country and outside the military barracks.Footnote 18 Sources from CISA attest to the substantial mobilization of the members of the armed forces who opposed and resisted military rule in Brazil. They highlight the need to go beyond categorizations that identify officers and soldiers after 1964 as either moderates or hard-liners and to examine the thousands of cases of members of the forces who opposed and resisted the regime in Brazil.

Imprisonment of Officers and Soldiers in the Wake of the Coup

News of the ousting of president João Goulart on April 1, 1964, led officers and sergeants who opposed military intervention to react in different ways. When a group of about 400 students from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro gathered in front of the university's law school in protest, police forces in support of the coup arrived with automatic machine guns to end the students’ demonstration.Footnote 19 Captain Ivan Cavalcanti Proença, an Army captain who served in the First Cavalry Regiment in Rio de Janeiro, heard about the conflict and decided to protect the students. He confronted the armed group, even though as an Army captain he was not authorized to leave his post to do so. After helping students escape from the building, the captain returned to his post at the Ministry of War. When he arrived, a lieutenant had already told Proença's superiors about his actions. Two superior officers accused him of taking the students’ side and being one of the “red ones.”Footnote 20 He was imprisoned immediately and kept at the Fort of Santa Cruz and then at Fort Imbuí for 58 days.

Proença understood that by breaking military hierarchy he would face disciplinary action. As such, his imprisonment did not shock him. Some officers who were expelled from the forces during this period, however, seemed to have been surprised when they were detained because they had not committed any acts that would qualify as resistance to the coup. Paulo Pinto Guedes, for example, an Army lieutenant colonel who served as National Security Council secretary-general during Goulart's presidency, did not react against the coup but was still imprisoned. On April 4, military authorities sent Guedes to Rio de Janeiro, where he was imprisoned at the First Military Region headquarters.Footnote 21 Although Proença's prison order had come after his alleged communist acts in helping university students, the officers who imprisoned Guedes did not immediately accuse him of subversion. After he was incarcerated, Guedes learned he was being accused of voluntarily participating in president Goulart's government, and that this was grounds for his imprisonment and expulsion from the forces. A military police inquiry (inquérito policial militar, IPM) accused Guedes of the crime of supporting the former president's subversive acts and of not questioning his authority: the least he should have done, they said, was to “resign from the post he occupied voluntarily.”Footnote 22 Therefore, Guedes was labeled a communist and expelled from the forces because he had worked closely with Goulart. This proximity to the ousted president automatically made him a communist in the eyes of the leaders of the military coup.

The regime also expelled some high-ranking officers before they could react to the military intervention. Officers who conspired against Goulart knew the president had supporters inside the armed forces who would attempt to resist the coup, so they acted quickly to stop any opposition movement from gaining strength inside the institution. On April 1, Air Force brigadier Francisco Teixeira and other officers met to evaluate the viability of an immediate reaction to the coup. After determining that they had very little chance of success—they had come to believe that Goulart was not willing to resist his ouster—they decided not to take action.Footnote 23 On April 5, brigadier Armando Perdigão and two colonels arrived at Teixeira's house with an order of imprisonment.Footnote 24 Teixeira was sent into the military reserves during the time he was imprisoned, and one month after his release was dismissed from the Air Force.Footnote 25 Brigadier Rui Moreira Lima, who received several medals of honor for participating in 94 missions in World War II, was also expelled from the Air Force and imprisoned for subversion. On the day after the coup the military government ordered him to leave the command of the Base Aérea de Santa Cruz for opposing the ousting of president Goulart. Beyond imprisonment and the termination of political rights, military pilots like Moreira Lima also had their flying licenses revoked, which prevented them even from piloting private airplanes.Footnote 26 This was also the case of lieutenant Roberto Baere, another Air Force pilot. After 50 days of imprisonment, the lieutenant was purged and had his flying license revoked.Footnote 27

Sergeants’ and soldiers’ experiences with imprisonment and harassment by the military government were largely harsher than officers’ experiences. Army sergeant Astrogildo José Deponti, whose superiors saw him as a supporter of leftist politician Leonel Brizola in Rio Grande do Sul, was asleep when a group of soldiers surrounded his home at 2:00 am on April 3. The group held him for 14 days at a warehouse, where they interrogated him every day and gave him constant beatings. Afterward, he was sent to the Department of Political and Social Order (DOPS) of Porto Alegre, where he stayed for 45 days. He was released but required to report to DOPS every 15 days, and every time he was tortured again.Footnote 28 Arlindo Mendes da Rosa, an Army sublieutenant in Rio Grande do Sul, was accused by the Superior Military Tribunal of being part of a group officers and sergeants who dedicated their time to speak publicly in favor of the Goulart government's policies. As a member of this group, Mendes da Rosa was accused of proselytizing for “Sovietizing” political programs, which “after leading the country into anarchy,” would “communize” it.Footnote 29 He was also imprisoned at a military base for two months.

In Rio de Janeiro, the sailors who were members of the Associação de Marinheiros e Fuzileiros Navais do Brasil (AMFNB) were among the first to be imprisoned under the new regime. By October 1964, 170 sailors and marines who had participated in an AMFNB meeting that took place a few days before the coup were excluded from the Navy.Footnote 30 Soldiers who were not affiliated with political movements were also imprisoned. Several soldiers of the Air Force who claimed they had never participated in political activities were nonetheless expelled and harassed, because their superior officers believed they had revolutionary connections. Many soldiers I interviewed claimed the Air Force had imprisoned, tortured, and expelled them because they knew a political prisoner, or owned what the authorities considered to be “subversive material”—flyers about political rallies, books written by leftist authors, or even albums of leftist musicians. Norberto Batista Simões, for example, was imprisoned and tortured because he knew one political prisoner at the Base Aérea do Galeão, where he served. This prisoner, who was his neighbor, asked Simões to tell someone about his whereabouts, and when his superiors found out Simões had helped the prisoner, they accused him of subversion. He endured torture regularly and had to work for the Air Force under dire conditions for four years. Only in 1969 did the Air Force discharge him.Footnote 31 Ataíde de Moura Lemos, another soldier who was expelled from the Air Force, claimed his superiors found literature he owned about two politicians, Leonel Brizola and Darcy Ribeiro, and accused him of being a communist.Footnote 32 These cases show that the generals who took governmental power acted preemptively, imprisoning and expelling even those who had not opposed the coup but could potentially do so.

Some members of the armed forces targeted for imprisonment by the military government were able to escape. A few went into exile and did not return to Brazil until the end of the dictatorship, but the military police were able to eventually detain many who initially escaped.Footnote 33 It also took the police a few months to identify some they considered “subversive” officers and soldiers and plan their arrest. This was the case of sublieutenant Emígdio Mariano dos Santos, who the Army believed was a communist infiltrator. Instead of immediately imprisoning him, the military police decided to use him to capture other individuals they believed were “communists.” One month after the coup, a soldier posing as a leftist activist lied to Dos Santos and gained his trust, claiming he wanted Dos Santos's help in organizing a resistance movement. The man, who called himself “Trajano,” got close to the sublieutenant and became part of a small group that wanted to challenge the dictatorship. The impostor gathered information about everyone involved, and when the police proceeded to capture members of the group they already had proof Dos Santos and his group were plotting against the dictatorship.Footnote 34 The Army police kept Dos Santos in the basement of their headquarters for 12 days in September 1964 and then transferred him to solitary confinement for two months. During his time in prison he was expelled from the Army.Footnote 35

These cases demonstrate how much effort and energy military authorities employed to cleanse the armed forces of any kind of opposition. Decrees called Institutional Acts, issued throughout the era, allowed military presidents to expel officers and soldiers from the armed forces, sending them to the military reserves, retiring them, or simply dismissing them.Footnote 36 In many cases, the government forcibly retired highest-ranking officers, sent junior officers to the military reserves, and dismissed many sergeants and low-ranking soldiers. Certain officers were also sent first to the military reserves and months later dismissed, as was the case with brigadier Teixeira, who was fired from the Air Force one month after he was released from prison. Although many officers were retired or transferred to the reserves, which in theory meant they would still receive pensions, this did not mean they transitioned peacefully to a life outside the military.Footnote 37 This kind of transfer was a quieter way for officers in power to remove many of their colleagues from the military ranks, especially colleagues who they saw as subversive but who still held social capital and a certain degree of influence in society. Nevertheless, these high-ranking officers were expelled for political reasons when they were still young enough to continue actively serving in the military. The practices of sending officers to the reserves and retiring them, while firing many low-ranking soldiers, perpetuated the hierarchy of the armed forces, even as these men were being expelled from their ranks.

Lower-ranking soldiers and sailors, sergeants, and junior officers faced more drastic expulsions than higher ranking officers. Military rank was the main factor that determined whether an expelled member of the forces was tortured while imprisoned, at least during the first few years after the coup. The approach to imprisonment was also respectful of military rank during those years. Officers who enforced the coup approached colleagues who opposed military intervention and imprisoned them. A few weeks after these officers and sergeants were captured, the orders for their expulsions were published in the Diário Oficial, the official vehicle of communication of the Brazilian government. Lower-ranking soldiers, on the other hand, were usually approached by sergeants and were not always expelled through the Institutional Acts: many were dishonorably discharged, and others had their superiors inform them that they were working under a military contract that had expired. Although these individuals had different ideological backgrounds, all were treated as communists who had to be neutralized.

First Reactions to the Coup

Despite the efforts of the generals in power to damper military opposition inside the armed forces, many expelled officers and soldiers continued fighting against the regime outside the military barracks. Even before Goulart was ousted in March 1964, many officers who supported him had strategized ways to stop the coup from taking place. However, after realizing that the conspiracy had a lot of support and that the planning of the coup was already in an advanced stage, they decided to refrain from further involvement. During the first years of military rule, officers such as Army colonel Paulo Pinto Guedes and captain Ivan Cavalcanti Proença decided not to openly challenge military rule. While opposing and resisting the dictatorship by not taking part in the military government, these officers, who had never been involved in political activism outside of the armed forces, stayed out of more structured political movements. One of the most important factors that discouraged these and other officers from open resistance was watching president Goulart fail to handle the democratic crisis of 1964.Footnote 38 Remembering the events of March 31, some officers who supported the ousted president claimed that in the weeks prior to the coup Goulart did not believe there was a conspiracy against him, and on the days following the coup he fled to Uruguay instead of fighting against the coup. If the president himself was not willing to resist, many of his supporters in the armed forces assumed they did not have the support to do so.Footnote 39

Ivan Cavalcanti Proença claimed that before the coup supportive officers had attempted to tell the president that certain officers were conspiring against him. Both brigadier Francisco Teixeira and Army lieutenant José Wilson da Silva confirmed this.Footnote 40 Da Silva claims he wrote reports about some of the men who conspired against Goulart and who made plans to imprison “communist” members of the armed forces. Goulart, however, did not believe these reports, as they implicated men who he believed were his allies.Footnote 41 Teixeira also stated that he called the president's office to suggest some initial steps to avoid a political crisis, but that the president did not take them into consideration. When some officers among Teixeira's troops expressed their wish to meet the president in Rio Grande do Sul and gather forces to resist the coup, Teixeira revealed that Goulart had not contacted him about resisting. He believed the president was not able to deal with the military crisis because he did not have competent military counsel during his time in office.Footnote 42

Proença claimed that it would have been possible to prevent the coup peacefully by imprisoning the most invested conspirators. He felt that if Goulart had neutralized these antagonistic forces, the coup could have been avoided—the elimination of those actors would have dissuaded other officers who decided to join the coup only at the last minute.Footnote 43 However, Goulart did not take action and did not change the commands of the military bases, as he thought such action would anger his opponents even more and thus strengthen a conspiracy against his government.Footnote 44 While it seems that some expelled officers like Guedes opted to abstain from public political actions or involvement with resistance organizations in the following years and tried to live quiet lives, others, such as Teixeira and Da Silva, decided to resort to different strategies to attempt to bring down the dictatorship.

The men who did decide to resist the dictatorship disagreed about the methods to use. Teixeira, albeit opposing the dictatorship, did not agree that armed struggle should be looked to as a tactic of resistance. Like Proença and Guedes, he had been a supporter of João Goulart, coming from a Varguista tradition.Footnote 45 Proença and Guedes, however, were never involved in political parties or activist movements outside of the armed forces. In the first months following the coup, Teixeira joined a group of military opponents of the dictatorship.Footnote 46 Initially, Teixeira agreed with the group that a military offensive coming from the barracks was ideal. He believed that a military insurgency starting in Rio Grande do Sul, where Goulart had the most support within the military, could be viable with the support of Leonel Brizola and Goulart, who were living in Uruguay.Footnote 47 However, due to increasing hostilities between the two politicians, this plan fell apart. Teixeira did not believe that other types of armed reactions to the coup that would involve the Brazilian population were viable.Footnote 48 The former officer trusted that the failed attempts of a military offensive indicated that the best strategy of resistance was through unarmed popular political mobilization.

Many expelled officers resisted the regime by simply not agreeing to serve in the military while interventionist officers were controlling the armed forces and the state government. Many believe that some officers who opposed intervention decided to keep quiet and proceed with their careers in the institution.Footnote 49 Others, however, claimed they could not serve with officers who enforced the authoritarian state. Proença, for example, rejected an offer, a sort of compromise, from his superiors. After spending 40 days imprisoned at Fort Imbuí, he met with four generals who proposed that he accept a transfer to an isolated military region in Campo Grande, in Mato Grosso, where he would be allowed to continue his Army career. In return, Proença would agree not to get involved in political actions and would not be imprisoned again. The captain, however, understood that this required him to consent to the decrees and actions of the military government and to work with coup leaders and its supporters. He rejected the proposal and was expelled from the Army the next day.Footnote 50

Armed Insurgency

In addition to everyday acts of resistance, some expelled members of the forces organized armed movements against the dictatorship.Footnote 51 Two of the first organizations created in opposition to military rule were run by former officers and sergeants. These were the Nationalist Armed Resistance (Resistência Armada Nacionalista, or RAN), created with the support of politician Brizola, and the Caparaó Guerrilla Movement (Guerrilha do Caparaó), implemented at Caparaó mountain between the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo. In the days following the coup, lieutenant José Wilson da Silva realized that the Army was seeking to imprison him and decided to go into hiding. In the first weeks after the coup, he and a group of officers attempted to create a resistance plan that involved mobilizing military troops in the south. After 20 days in hiding, Da Silva recognized that the plan could not be implemented immediately because it had little civilian support, and he decided to move to Uruguay. There, he and other expelled officers and sergeants in exile created a network of about 470 individuals (in Brazil and in exile) who were willing to participate in an offensive against the regime, which would start in Rio Grande do Sul.Footnote 52 Colonel Átila Escobar evaluated the support of the Brigada Militar (the Rio Grande do Sul military police force), and former Air Force captain Alfredo Ribeiro Daudt coordinated soldiers and civilians in Porto Alegre. Former colonels José Lemos de Alencar and João Guerreiro Brito, as well as a few other purged officers kept up their relationships inside the Army to assess how much support they had in that military branch. In addition, a group of about 21 purged sergeants expressed their willingness to participate in an armed offensive against the officers in power.Footnote 53 This network led to the creation of the Nationalist Armed Resistance.Footnote 54

A few months after this group started to organize a counter-coup, the Brazilian military intelligence service found out about its plans. In October 1964, the Centro de Informações da Marinha (Navy Intelligence Center, or CENIMAR), circulated a report about the existence of a political apparatus formed mostly by former military personnel. “Sá” was the alleged leader of the group of sergeants who sought to create a network of all groups who were willing to fight against military rule through armed insurgency. Their plan was to take control of a region between Goiás and Mato Grosso, where they would establish an operational base. According to the document, this group had “200 men, money, and material conditions.”Footnote 55 CENIMAR and CISA continued informing on the activities of political exiles in Uruguay and trying to capture those they could find in Brazil in the following years. In April 1965, former Army colonel Jefferson Cardim de Alencar Osório and sergeant Albery Vieira dos Santos, together with a group of 16 men, were captured at the border of Santa Catarina and Paraná states with a plan to attack airports, military barracks, bridges, radio stations, and farms.Footnote 56

While former officers and soldiers prepared for a counteroffensive, government agents remotely monitored their activities in exile. As soon as they arrived on Brazilian soil, the police tried to apprehend them. Surveillance operations were extremely organized and detailed. The CISA archive, which is the only military intelligence archive even partially available to the public, contains a great number of documents pertaining to the whereabouts of the expelled members of the armed forces who were living in exile, including such details as places they visited, and which people they had talked to.Footnote 57 In a document from May 1966, an Air Force agent reported that many political exiles had met at former Navy admiral Cândido Aragão's house to approve the creation of Movimento de Resistencia Militar Contitucionalista, MRMN—which changed its name to RAN a few months later.Footnote 58 According to CISA, MRMN members were willing to conduct operations to destroy property, such as exploding cars, kidnapping, and attacking citizens of the United States who were living in Brazil. They would, however, avoid operations that could hurt Brazilian citizens. The MRMN envisioned a scenario in which their actions would increase state repression, which would in turn bring more individuals to the resistance movement. The final stage of the plan would be a broad-based armed insurgency, and a counter-coup. Officers expelled from the military who were still in Brazil, such as Francisco Teixeira, would articulate the implementation of these actions.Footnote 59

Conflicts within the movement started almost immediately, as members of MRMN were divided regarding guerrilla action and non-military involvement in an armed confrontation. While politician Leonel Brizola believed the best strategy for resistance was to have the former military in Rio Grande do Sul head a counter-coup, former officers such as Navy admiral Cândido Aragão believed in a social movement with the support and involvement of the masses, including urban and rural workers and students, that would result in guerrilla warfare. The CISA archives highlight that Brizola believed opponents to military rule first needed to exhaust the less violent resistance options, avoiding early involvement of the public in the fight, and also to prepare public opinion for the possibility of an armed struggle.Footnote 60 Da Silva claims that Brizola was able to convince Ferreira and other legalist officers and sergeants to try a military insurrection in the South and resort to guerrilla warfare with public participation only if the first approach was unsuccessful.Footnote 61

It did not take long for the military police to expose and defeat Brizola's resistance plans with the MRMN. In February 1967, the Air Force discovered that former sergeant Amadeu Ferreira was directing a plan of resistance. The report stated that Brizola had been responsible for organizing an armed offensive that would include 40 armed men and last 90 days. The movement, however, suspended the event, which would have taken place in December 1966 in Mato Grosso. The police believed that Brizola postponed it to make it coincide with other resistance actions that were being organized throughout Brazil.Footnote 62 By October 1967, due to disagreements that caused splits in the group, the movement of former officers and soldiers in Uruguay had lost many members, and the MRMN, which had changed its name to Resistência Armada Nacionalista (RAN), was functioning with a lack of resources. The Air Force Intelligence Agency, CISA, continued informing on RAN members and former members into the 1970s. However, their reports on the organization drastically decreased after 1968, which indicates that the regime did not believe RAN was as threatening to the maintenance of the military government then as it had been in 1966.Footnote 63

The Guerrilha do Caparaó Movement

While the former members of the armed forces living in Uruguay were trying to keep the resistance movement alive in exile, a number of sergeants became tired of waiting for Brizola's plans to unfold and decided to develop a different strategy. Because the attempts at insurrection were failing one after another, the group of sergeants who had been planning the creation of a guerrilla movement at Serra do Caparaó decided to implement it at the end of 1966. This decision represented one of the most important splits within RAN: while some members wanted to implement the plan at Caparaó, others strongly rejected the idea of guerrilla warfare. Francisco Teixeira, for example, considered that guerrilla tactics could scare the population and backfire, strengthening the regime.Footnote 64

The Guerrilha do Caparaó was a short-lived movement, established in the Caparaó mountains and comprised mainly of expelled members of the armed forces.Footnote 65 Years after its end, some of its former members admitted that the movement had had support from Cuba and was part of a larger project to fight capitalism in Latin America. The men who joined the movement spent eight months in Cuba receiving training in guerrilla tactics used in the jungle and the mountains. At the end of 1966, former sailor Avelino Capitani and other expelled officers and soldiers returned to Brazil and headed to Caparaó to implement their own guerrilla movement.Footnote 66 The military government was confident that Cuba's participation in the movement, providing training and resources to Brazilian guerrilla members, made the island a major coordinator of the group.Footnote 67 Nevertheless, although the guerrilla group received support from Cuba, it was not being manipulated by the nation as the Army's report suggested. Nonetheless, the military government in Brazil used a Cold War narrative that centered the Caribbean nation as the main articulator of guerrilla movements in Latin America, overplaying its role in Caparaó. A close analysis of the events that took place in Caparaó in the beginning of 1967 and the intentions of its organizers show that Brazilians built and implemented the movement autonomously, addressing local problems and concerns. The Caparaó guerrilla members shaped their mobilization as a fight for national autonomy and democratic participation, looking to Cuba, as well as to China and Vietnam, as examples of revolutionary success. As Avelino Capitani stated it, “If Cuba could do it, so could we.”Footnote 68

The movement, however, did not last. Before its members could perform any actions against the regime, the military government found out about its existence and location. In November 1966, several Brazilian intelligence agencies started to investigate reported guerrilla activity in the region of Caparaó.Footnote 69 The police organized daily trips to study the territory and search for members of the movement. By March 1967, the police had already identified a group of up to 40 armed men living in the mountains.Footnote 70 When the police of Minas Gerais captured two of the men, former second-lieutenant Jelcy Rodrigues Correa and sergeant Josué Cerejo Gonçalves, the press found out about the guerrilla activity in the region and made it public. In April, when one man became ill, the rest of the group decided to leave the mountains and go to the nearest town to purchase medication. Eight members of the Caparaó movement set camp close to a trail and were discovered by the police, who sent 30 soldiers to capture them.Footnote 71 By mid April, the police had captured the rest of the group in Caparaó, including former captain Juarez Alberto de Souza Moreira, sublieutenant Itamar Maximiniano Gomes, and sergeant Deodato Baptista Fabrício.Footnote 72 All told, the Caparaó Guerrilla Movement lasted less than six months. Twenty-one members of the movement were prosecuted for their participation, and many others were investigated for their involvement in providing support to the group's activities.Footnote 73

The operations leading to the capture of Caparaó guerrilla members did not immediately result in armed confrontations or deaths. The historical context of 1967 and the amount of media coverage the case received informed the police's careful methods in detaining the men of Caparaó. From 1964 to 1967, president Castelo Branco was relatively concerned with the public image of the regime, particularly in regard to the enforcement of legal procedures. To this end, the first military government attempted to preserve some aspects of the legal and justice systems in use before 1964.Footnote 74 This included prosecuting political prisoners and allowing them to face trials, for example. The president's goal was to transition power back to civilians once the military had rid political spaces of communist influence. Therefore, although the police did conduct operations that resulted in the killing of individuals seen as enemies of the state, the general direction of the regime was to respect certain judicial rites, including trials and prison time for “subversives.” This situation changed later, especially during the governments of Arthur da Costa e Silva and Emílio Garrastazu Médici, when the order became eliminating “the communist threat” at all costs. With the implementation of the Fifth Institutional Act and increasing media censorship, guerilla members faced harsher consequences; the ones who were caught were often killed during a confrontation with the police or during interrogation.Footnote 75

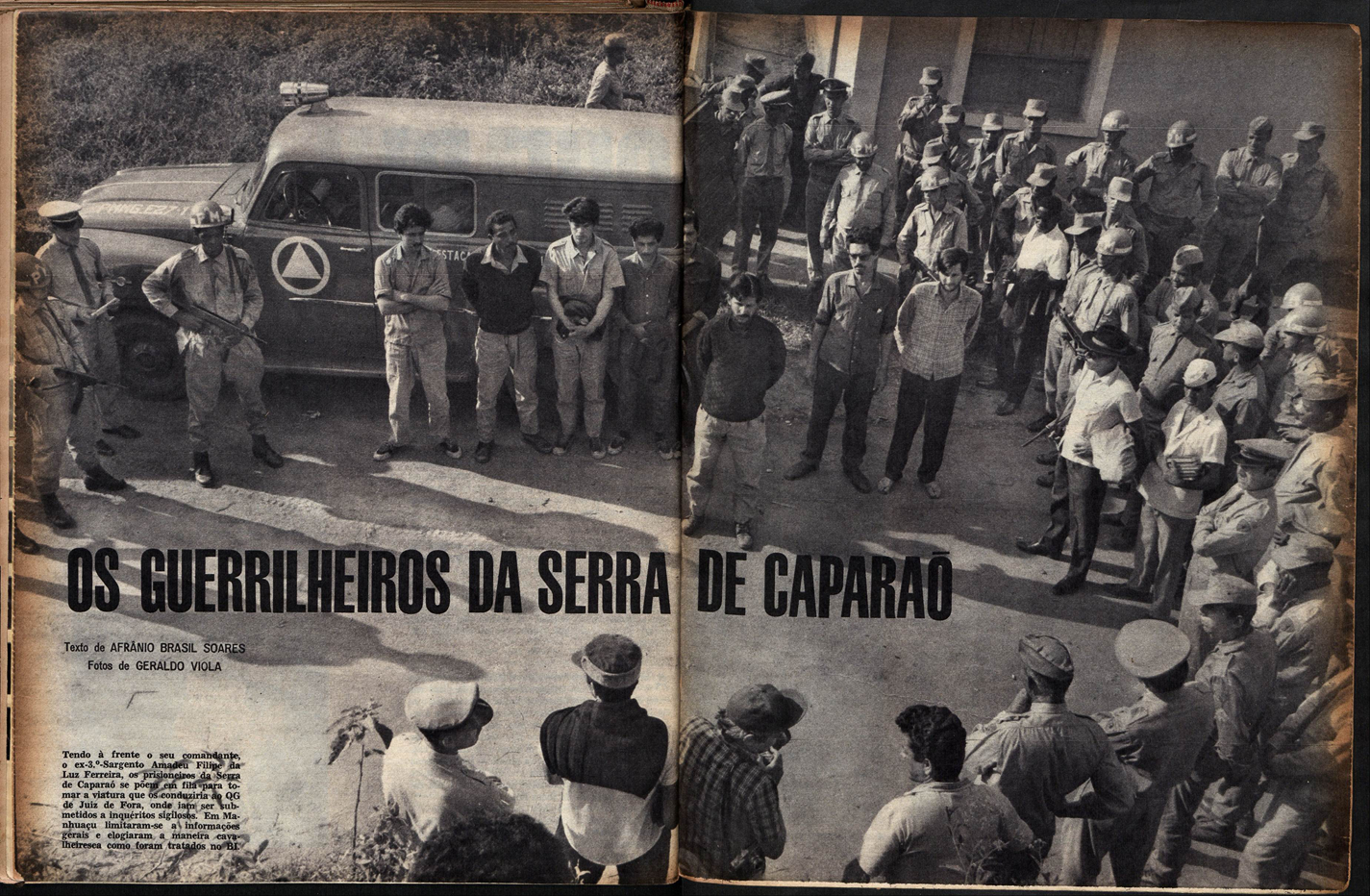

Despite media censorship and the press's careful reporting of the regime's actions, news about the Caparaó guerrilla movement attracted a lot of public attention. Just a year before, in August 1966, Manuel Raimundo Soares, an expelled sergeant who joined the resistance movement, had been detained and killed by the police.Footnote 76 His story exposed the military regime as a repressive force that killed its opponents. Thus, when the case of Caparaó became public, the military government, which transitioned to Costa e Silva's leadership in April 1967, responded strategically to improve its image with the public. On April 15, 1967, the magazine O Cruzeiro published a six-page article about the capture of eight members of Caparaó. In the picture that underlay the first and second pages of the article, the eight men stand, unharmed and uncuffed, surrounded by a group of about 40 policemen and three photographers and/or journalists (see Figure 1). The composition of the photograph suggests its careful staging. Portraying the detained men in a structured, nonviolent setting was intended to highlight the capture operation's nonviolent character, providing a counter-narrative to accusations that the regime tortured and killed all of those who opposed it. At the same time, the picture also projects a disciplined and well-structured image of the regime and the police. With this picture, these institutions communicated that although they respected human and civil rights, they had the resources to fight and end movements that opposed the regime.

Figure 1 Captured members of the Caparaó movement, surrounded by police and journalists

The Caparaó guerrilla were judged and convicted, receiving sentences that ranged from four to 15 years of jail time. Some of them, such as Amadeu Felipe da Luz Ferreira and Jelcy Rodrigues Corrêa, were released from jail after serving four-year sentences; others, such as Avelino Capitani, escaped from prison and joined other movements of resistance.Footnote 77 During the time they were in jail members of Caparaó were tortured. At least one of them died in jail, an event the police accounted for as a suicide even though some of his colleagues believed he was executed.Footnote 78

United Against the Coup

Officers and soldiers interpreted, and embraced or rejected, the ideologies that marked the era of the Cold War in different ways. While some identified with communist ideology, as did the men who fought in the Caparaó Guerrilla Movement, others believed in a strong state that would control certain resources but encourage private enterprise. The officers who were expelled from the forces in the wake of the coup were mainly constitutionalists or legalists, not communists. Most of them shared two principles: nationalism and a strong opposition to military interventionism. Collectively, they positioned themselves against the ousting of president Goulart, military rule, and the influence of the United States in Brazil. They supported the maintenance of the constitution and the democratic process. Therefore, although diverging in tactics, expelled members of the forces who opposed the coup had similar principles in their fight against the dictatorship.

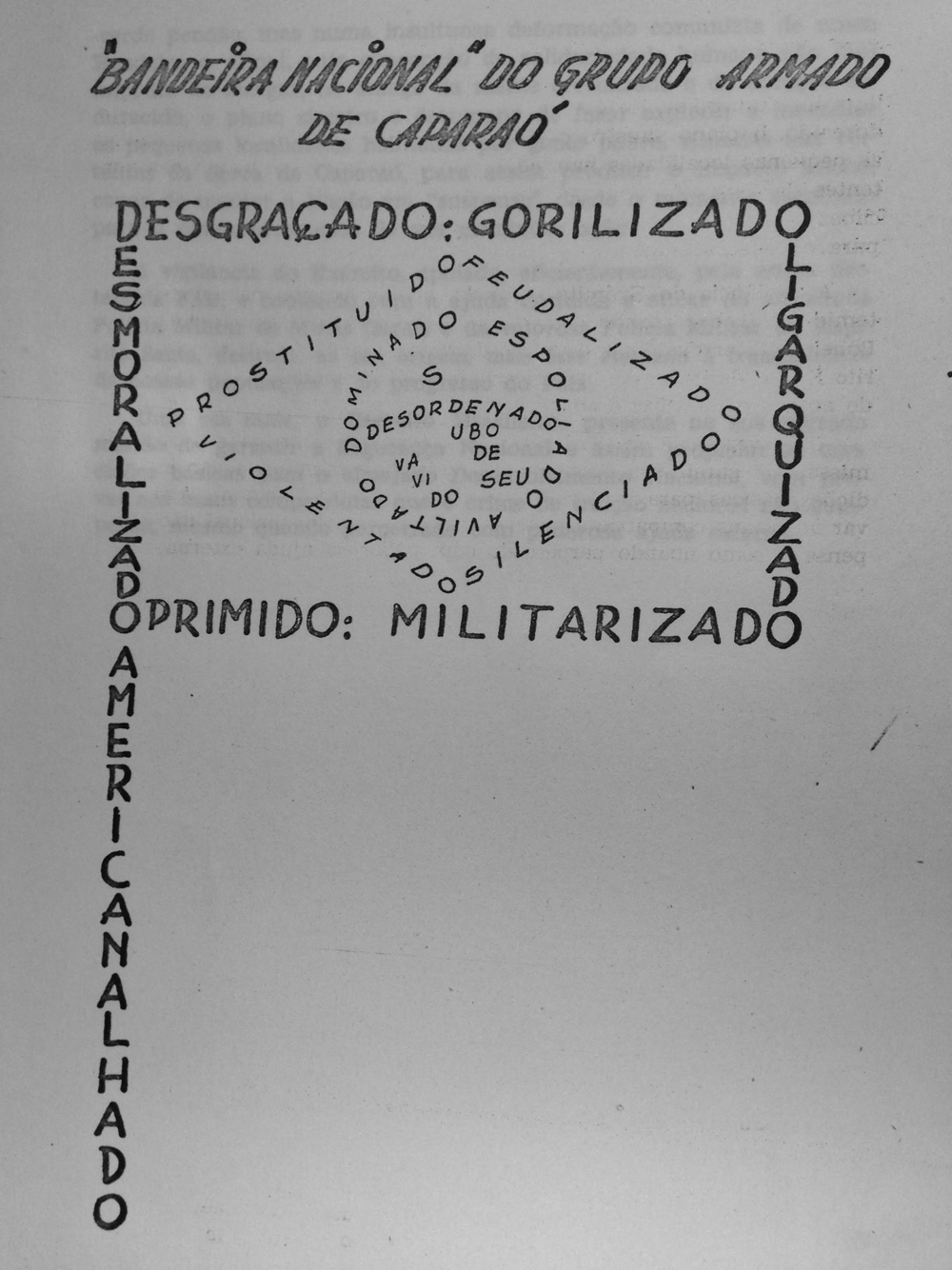

Members of the Guerrilha do Caparaó communicated what they believed military rule represented in a drawing of a modified version of the Brazilian flag (Figure 2). It is possible to identify in this flag a strong anti-interventionist and pro-nationalist ideology that condemned the influence of US interests in Brazil. The group criticized interventionist officers for having transformed Brazil into a country that was “disgraced, oligarchized, oppressed, militarized, demoralized, Americanized, prostituted, feudalized, violated, silenced, dominated, plundered, demeaned, disordered and gorilizado”—from ‘gorilla,’ which was how interventionist officers became known inside military circles. The words ‘disgraced, oppressed, militarized, demoralized, violated, silenced, demeaned, disordered, and gorilizado’ represented accusations of the violent aspects of authoritarianism, especially the increasingly repressive role of the police under military rule in subjugating the population and silencing its opponents.

Figure 2 National Flag of the Guerrilha do Caparaó

Members of Caparaó believed the Brazilian population was living under an oppressive military order. They also used the terms “oligarchized and feudalized” to condemn the fact that a small group of elites were governing the country. They were referring to the military elites who implemented the coup, but also to the interests of economic elites in Brazil and abroad that were contributing to and benefitting from this order, such as private companies, multinationals, and other anticommunist groups, namely represented by the Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos Sociais (IPES) and the Instituto Brasileiro de Ação Democrática (IBAD).Footnote 79 Members of the Caparaó guerrilla movement accused these elites of controlling Brazil and using the country for their own personal benefits. The last words on the flag, “Americanized, prostituted, and plundered,” represented an outcry about the role and support of the United States in the military regime. Although the flag represents the sentiments of members of the guerrilla movement who identified with the communist ideology more than others, most of the men I interviewed who opposed the coup expressed similar anti-interventionism and nationalism. In his interview, Proença, for example, talked about the influence of IPES and IBAD in the implementation of the coup. He claimed these institutions were responsible for creating propaganda to manipulate the population into believing there was a real risk of Brazil becoming a communist nation, which raised support for military intervention.Footnote 80 Proença, José Wilson da Silva, Francisco Teixeira, and others who never participated in the guerrilla movement criticized military rule for the same reasons the members of Caparaó did.

One of the strongest sentiments that circulated among legalist officers who supported the policies of former president Getúlio Vargas (1930–45, 1951–54), including Proença and Da Silva, was an economic nationalism that rejected US influence in Brazil. This sentiment emphasized that the South American country should explore its own natural resources and revert the profits to its population. This idea was strongest during Vargas's O Petróleo é Nosso campaign in the early 1950s, which was dedicated to keeping petroleum a public national enterprise.Footnote 81 Private multinational corporations pressured the Brazilian state to grant them exploration rights, but these “nationalist” groups fought to keep petroleum a national and state enterprise. In this context, Vargas created Petrobrás, the state company that had monopoly over oil exploration in Brazil. Among the legalist officers who were expelled in 1964, many were influenced by this economic nationalism and believed that the riches that were generated in Brazil should have stayed in the country. Revenues generated by the exploration of natural resources should have been reverted to the general population, instead of allowing international companies, especially those from the United States, to exploit the wealth and send the profits to their headquarters. The words ‘Americanized, prostituted, and plundered’ were a direct claim by members of Caparaó that military leaders were prostituting Brazil to the interests of the United States, which stood to benefit from the military regime ransacking the country's resources. However, these words also represented sentiments shared by legalist officers who did not believe in the armed struggle.

Therefore, even though the flag in Figure 2 was intended to represent the beliefs of members of Caparaó, many officers who were never involved with guerrilla warfare shared the same ideals. Former officers often expressed a belief that countering US interests in Brazil was central for the viability of the coup. Teixeira, for example, claimed that the main force that coordinated the military movement for the coup and the political struggle against president Goulart was the US embassy.Footnote 82 Proença expressed a similar belief, claiming that it was not advantageous for the United States's imperial interests that a country of Brazil's size and potential implement the reforms Goulart proposed. The Army captain believed the United States supported the military coup in Brazil because it wanted to prevent the South American country from becoming a powerful economic and political force in the region.Footnote 83 Sergeant Almoré Zock Cavalheiro, who was also expelled from the Army in 1964, claimed that US officers had trained Brazilian military personnel and “brainwashed” officers at the Academia Militar das Agulhas Negras—the largest school for combatant officers of the Brazilian Army—into thinking according to US interests.Footnote 84 Therefore, even though members of the Caparaó Guerrilla Movement created this flag, it relates to the larger movement of military opposition to the dictatorship.

In addition to revealing the guiding principles of many officers and soldiers who opposed the dictatorship, the flag placed the fight of thousands of members of the armed forces against authoritarianism within the context of the global Cold War, as part of a larger struggle that advocated for Brazilian economic autonomy and sovereignty. This aspect of the flag shows that militarism in Brazil went far beyond an interventionist ideology supported by only moderates and hard-liners. While officers who enforced military rule in Brazil fought over how long they would keep governmental control, what characterized subversive actions, or how they would end communism in Brazil, non-interventionist officers and soldiers rejected these premises and engaged in developing different strategies to resist the dictatorship.

Although not all expelled soldiers were conscious of the reasons that led to their expulsions, the ones who resisted the dictatorship were. They were also aware that the circumstances of their struggle had changed. If before the coup they had fought against an interventionist conservatism inside the military, they now fought against forces that exerted influence and control outside the barracks. The military interventionism and internationalism within the armed forces spread outward to become the ideology that governed Brazil, and expelled officers and soldiers who opposed military rule believed they would have to pressure coup leaders and supporters to return to the barracks. The struggle of expelled soldiers makes clear that they could not all be categorized as moderates or hard-liners. Just as the civilians who resisted military rule during the period, their role was now to stop this military ideology from disgracing, oppressing, militarizing, demoralizing, violating, silencing, and demeaning the population, both inside and outside of the armed forces. After the 1964 coup, the fight of non-interventionist and nationalist officers became the fight of all Brazilians who opposed military rule.

Conclusion

Although the political views and experiences of the men considered here differed, all of them were purged from the armed forces because coup leaders believed they could potentially challenge the coup. Using a rhetoric that condemned breaks in military hierarchy, communism, and subversion, the interventionist generals who took power in 1964 made a clear effort to cleanse the armed forces of opposition. In most cases, these expulsions were used as a preventive measure against the emergence of insurgency movements opposed to the coup from within the barracks. The regime's opponents inside the armed forces were to be neutralized and kept from access to arms and other resources that could be used against the dictatorship. However, being expelled from the institution did not stop many of them from continuing to challenge interventionist officers, and their non-interventionist and nationalist ideologies led them to the forefront of the resistance movements.

The disagreements among the officers and soldiers examined here who opposed military rule as to which strategies were practical and which would be most effective in fighting the regime led to the creation of different organizations and movements. However, there was a set of beliefs that united those who resisted the coup. While they were divided between those who aimed to create guerrilla movements and those who did not believe the armed struggle would be successful or should even be considered, a nationalist sentiment strongly connected to Brazil's economic and political sovereignty guided the actions of most military opponents of the regime. Those who did not share the beliefs of interventionist and internationalist officers before 1964 continued fighting against that ideology, but now outside the military. Although the officers in power were successful in neutralizing most of the dissent within the forces, the regime's military opponents reconceptualized their opposition to interventionism, challenging the regime. They resisted outside the armed forces, forming alliances and movements with other officers and soldiers, and with civilians and politicians. The opposition efforts of non-interventionist and nationalist members of the forces became the efforts of thousands of Brazilians who fought against military rule until 1985.

Throughout this cycle of authoritarianism in Brazil, soldiers continued to be accused of subversion and expelled from the armed forces. Nevertheless, they persisted, using everyday tactics of resistance to survive persecution. Members of the short-lived organizations RAN and Caparaó continued resisting the regime, building different strategies and movements of opposition within Brazil and in exile. Those who participated in guerrilla movements after 1968, however, faced a more drastic fate than those who did so in the first years of military rule. The Fifth Institutional Act, issued in December 1968, closed the congress, instituted a stricter national security law that allowed the government to detain anyone and strip them of their political rights, suspended habeas corpus in cases of political crimes, and outlawed political meetings, strikes and demonstrations.Footnote 85 The effect of the act was to increase political persecution in Brazil. Between 1968 and 1974, the police tortured and killed opponents of the regime more consistently than during the first years of the dictatorship.