INTRODUCTION

The people play with terror and laugh at it; the awesome becomes a “comic monster” (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1984:91).

In the years since Dibble and Anderson completed the monumental task of translating the Nahuatl text of the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982), the large extant corpus of colonial Nahuatl alphabetic writing has received a significant amount of attention from scholars. One subcategory of this corpus, however, remains under-studied: the diverse spectrum of writing of a religious nature, which includes Indigenous-language doctrinas (catechisms), sermonarios (collections of sermons), and literature of a devotional nature. Despite important contributions (Alcántara-Rojas Reference Alcántara Rojas2005, Reference Alcántara Rojas2013; Burkhart Reference Burkhart1989, Reference Burkhart1996, Reference Burkhart2020; Christensen Reference Christensen2013, Reference Christensen2016; Tavárez Reference Tavárez2011, Reference Tavárez2013), the study of colonial Nahua “Christianities” through the translation and analysis of Nahuatl religious texts is a field with many opportunities for new research. Texts of this class contain a wealth of cultural and linguistic data, as each of the studies referenced above attest. Of particular interest are Nahuatl presentations of the Church's teaching on hell and the Final Judgment (Leeming Reference Leeming2012, Reference Leeming2017). These subjects frequently constitute what Olko (Reference Olko2018) has referred to as “loci of meaning,” moments in a text where Native writers linger to elaborate on foreign material in such a way that allows Indigenous meanings to surface. This article collects and analyzes lexical data from two such “loci of meaning”: descriptions of demons and sinners. Although these figures bear some resemblance to their Medieval counterparts, data collected for this paper suggest that in some instances Native authors also drew on pre-contact sources when fashioning their descriptions. In particular, I will argue that in certain instances writers transformed these frightening and pitiful characters destined for hell into powerful, liminal beings who played an essential, balancing role in the spiritual economy. Native transformations such as these undermined the goal of Church teachings on hell and damnation, and laid the groundwork for the thoroughly indigenized manifestations of Christianity that persist all over Mesoamerica today.

What stands out in the data I have collected for this paper is the creativity Nahua authors employed in describing the physical features of their subjects. Specifically, these physical features often appear as exaggerated, hyperbolized, or deformed. Demons are described as having “sagging ears,” as being “jar-nosed,” and having “bowl lips,” while sinners are “fatsos” and “draggers.” In addition to these physical details, indigenized demons and sinners also tend to be marked by behaviors that can be termed aberrant or transgressive: they “raise and lower the head like a crazy person,” “scurry like mice,” “walk on tiptoes,” and “stumble around off balance.” These descriptions stand in contrast to the more formulaic (and, in my mind, European) ones which tend to describe demons and sinners in moral—not physiological—terms: they are “lazy,” “sinful,” and “drunk,” and no mention is made of “bowl lips” or “jar noses.”

This difference raises the first question I aim to address in this paper: What was the source of inspiration for descriptions like these? In what follows, I will argue that the most direct source was the wealth of ethnographic research that Franciscan friars and Nahua collaborators had collected between the 1540s and the 1570s. This material was most famously redacted into what has come to be called the Florentine Codex, the 12-volume ethnographic encyclopedia of Nahua culture whose creation was overseen by the inimitable Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún. The existence of analogous material in the sixteenth-century ethnographic corpus, however, necessarily forces us to look deeper into the past for sources of inspiration and clues as to their meaning. For this paper, I have identified a number of pre-contact Mesoamerican human and other-than-human beings whose physical and behavioral manifestations suggest they are linked to colonial descriptions of demons and sinners to be analyzed here. This cast of characters includes sculpted Olmec dwarfs, painted Maya “fat men,” and bawdy comic performers associated with the Mexica royal court. This motley crew of Mesoamerican freaks and funny-people constitute what I call the “monster-clown complex,” a constellation of beings and their associated traits with a long history in Mesoamerican cultures. Beings that fall within the monster-clown complex are human and other-than-human, giants and dwarfs, madmen and foreigners, entertainers and ritual specialists. What links together this disparate group are two common traits: they manifest their status as “other” in grotesque bodily deformations and aberrant behavior that transgresses social norms. Intriguingly, many of these figures are also performers whose physical deformity and transgressive antics were simultaneously frightening (hence “monsters”) and humorous (“clowns”). I believe that it was this monster-clown complex that certain Nahua authors drew on when composing descriptions of demons and sinners for the church's Nahuatl-language doctrinal writings.

The second question to be addressed in this paper has to do with the effects of such descriptions on Indigenous understandings of the categories of “demon” and “sinner.” Although it is difficult to know precisely what early colonial Indigenous audiences thought about anything, I believe a case can be made that by drawing on this ancient complex of beings and associated traits, demons and sinners were transformed into powerful entities more akin to ritual clowns than the frightening beings that haunted the Christian consciousness. Specifically, Nahua comic demons and sinners were stripped of the unambiguously evil moral status they held in the Christian context and instead were pulled into an ambiguous moral state where their actions could be deemed both ordering and disordering, welcome and unwelcome. Additionally, their comic nature may have made them laughable, a trait utterly at odds with the aims of the missionary friars who oversaw the production of written materials to be used in the indoctrination process. In this sense, laughter became an instrument of subversion, each chuckle one of a thousand cuts that in time eroded the effectiveness of the Church's message. Finally, the linking of demons and sinners to ancient and widespread Indigenous American traditions of ritual clowning facilitated the establishing of continuities with the pre-Christian past. Over the course of centuries this contributed to the flourishing of the multitude of Indigenous Catholicisms that today are practiced all over the Mesoamerican region (Christensen Reference Christensen2013:3–4).

SELECTION AND PRESENTATION OF DATA

Not every treatment of demons and sinners received the sort of creative elaboration that suggests they were loci of meaning. Although these moments are more common in some texts than others, in my experience they tend to be relatively rare overall, brief spasms of creativity where the Indigeneity of the writer bubbles up, only to subside again beneath the surface of the dominant Christian discourse. Therefore, the collection of data for this paper has, of necessity, been selective, a focused search for such fleeting apparitions. I surveyed dozens of sources, starting with significant imprints like the Dominican Order's Doctrina christiana of 1550, fray Juan de la Anunciación's Sermonario en lengua mexicana of 1577, the numerous titles that appear under fray Juan Bautista's name (including Reference Bautista1600, Reference Bautista1604, Reference Bautista1606), fray Juan Mijangos’ Espejo divino (Reference Mijangos1607), fray Juan de Gaona's Coloquios de la paz (Reference Gaona1582), the Confessionario mayor and breve (Reference Molina1565a, Reference Molinab) of fray Alonso de Molina, and others. I also examined many manuscripts, including the paraphrastic translation of the Imitatio Christi possibly by fray Luis Rodriguez and fray Juan Bautista (prior to Reference Rodriguez and Bautista1570), fray Andrés de Olmos’ Tratado de hechicerías (Reference Olmos1990 [1553]), Sahagún's Apendice and Adiciones a la postilla (Reference Sahagún and Anderson1993 [1579]), the Bancroft Library's early seventeenth-century Santoral en mexicano (see Schwaller Reference Schwaller1986:379–380), the Nahuatl religious plays published in Sell and Burkhart's Nahuatl Theater project (Reference Sell and Burkhart2004–2009), and others. The methodology I employed to narrow my search involved focusing on specific topics in the doctrinal literature that often involve descriptions of demons and sinners. These sources include expositions on the Seven Deadly Sins and the Fourteenth Article of the Faith and the Advent sermons, both of which discuss the Final Judgment. Similarly, I have also found the exempla genre to be a rich source of material on demons, sinners, and hell. Within these textual fields, I came to identify certain tell-tale signs of Indigenous influence, which in turn suggested they might be loci of meaning. These signs include the presence of Indigenous poetic structuring, such as the extensive use of parallel constructions, long lists of terms, and difrasismos (semantic couplets). As will be clear in the data below, another tell was the repetitious use of words formed by using Nahuatl's pejorative suffix -pol (singular) and -popol (plural). The addition of this suffix increases the size or nature of what it modifies in a negative manner. For example, tlatlacoani (“[he/she is a] sinner”) becomes tlatlacoanipol (“[he/she is a] big old sinner, miserable sinner, or wretched sinner”). In the hands of certain writers, the -pol suffix endowed writers with a tool with which to greatly extend the range of negative descriptors they could apply to their subjects, the results of which constitute some of the most evocative expressions preserved in colonial Nahuatl writing.

In selecting the representative examples that follow, I have had to shorten many passages out of consideration for space and the reader's patience. Additionally, since the amount of source material is vast, I propose that the following examples represent a small sampling of a larger pattern. Finally, because loci of meaning are not ubiquitous in the doctrinal sources, my data set is unavoidably selective; I have only collected those descriptions which appear to have been strongly shaped by the monster-clown complex. To be clear, I make no claim that all descriptions of demons and sinners in Nahuatl doctrinal texts were influenced by ancient Mesoamerica's monster-clown complex, but only that many of the most Indigenous in nature do.

Unless otherwise noted, all Spanish and Nahuatl translations in this article are my own (as are any resulting errors). The exceptions are Nahuatl quotations from the Florentine Codex, where Dibble and Anderson's translations have been used with only slight modification. In the presentation of all other Nahuatl quotations, the original orthography (either of the manuscript, imprint, or modern edition) has not been altered.

(1) Fray Juan Mijangos (Reference Mijangos1607:17), Espejo divino en lengua mexicana: Ca niman ahmo qualnezque, cenca telchihualonime: ixhuitlatzpopul, ixquayeque, canpoputztique, yacahuictique, yacacocotoctique, ixtlètlexochpopul, ixxocuichtique, ixpepetoctique, nacazhuihuilaxpopul, yacaxocuichpopul, itztapalteneque, tlexochnenepileque.

The [demons] are positively hideous! They are most worthy of scorn, the big old long-faces, forehead-fatties, plump-cheekies, long noses, busted noses, big old bloodshot eyes, grubby faces, pop-eyes, big old saggy ears, big old snot-noses, paving-stone lips, burning-ember tongues.

(2) Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1540:f. 60v), Siguense unos sermones…

Auh izca, in quenamique vmpa nemi tlatlacatecolo, ca tzitzimime, tzitzinteneq[ue] tenxaxacaltique, camacoyauaq[ue], tla[n]tepuzvitzoctiq[ue], tla[n]cocultique, tlecueçalnenepileque, ixtletlexochpupol, necoc ixeq[ue], tla[n]cochtetechcame noviya[n] tequa, noviya[n] tequetzoma, noviya[m]pa teca[m]paxotiuetzi, intech quique[n]ticac yn i[n]tzitzinte: yva[n] iztivivitlatzpopol.

And this is what the tlatlacatecolo [demons] who dwell there are like. Indeed, they are Tzitzimime, they have mouths like Tzitzimime, they have mouths like huts, they have gaping mouths. They have metal bars for teeth, they have curved teeth, they have tongues of flame, their eyes are big burning embers. They have faces on both sides. Their molars are sacrificial stones. Everywhere they eat people, everywhere they bite people, everywhere they gulp people down. They have mouths on all their joints like monsters with which they chew. And they have big long nails (Burkhart Reference Burkhart1989:55 trans.).

(3) Santoral en mexicano (17th c.:f. 318v)

Maçihui ȳ motlacanextique, cahmo ca çan iuhquin cacatzacpopol, tlilpopochecpopol, tlilquimilpopol, yuhquin tlecocollochpopol, yn intzō yuhquin tlecocototzpol, tlemamalichpol, tenhuitlatzpopol, yacahuitlatzpopol, yacahuicolpopol, yacamimilpopol, tencaxpopol, tenpahçolpopol, tlacahuiacapopol, tlacamecapopol, xohuihuitlatzpopol, yxteyáyáhualpopol, yxtepepetocpopol.

Although they appeared to be human in form, they certainly were not. They were just like big old filthy ones, big old smoky black ones, big old black bundles. Their hair was like big old fiery curls, like big fiery crinkles, big fiery tufts. [They were] big old long lips, big old long nose, big old jar nose, big old pillar nose, big old bowl lips, big old bushy lips, big old giants, big old human ropes, big old long legs, big old circle-eyes, big old pop-eyes.

(4) Fray Andrés de Olmos (Reference Olmos1990 [1553]:6), Tratado de hechicerías y sortilegios

Yoan uel yc omitzmomaquixtili yn inmacpa yn moyaohuan in tçonpachpopol yn cuitlanexpopol in tequanime yn tlatlacatecolo in Diablome.

And because of this he truly saved you from the hands of your enemies, the big old mossy heads, big old ash-covered ones, the people-eaters, the human horned owls, the devils.

(5) Sermonario en lengua nahuatl (17th c.:f. 4r)

Auh oquimocniuhti ce tlacatl tlahueliloc, teca mocacayahuani, tlaçiuhqui, antlan teittani. Auh in ye quinnotza in tlatlacatecolo, niman ohuallaque cenca icahuacatihuitze, tlacocomotztihuitze, tlatetecuitztihuitze. Auh in yehuatl in tlacatl, ca huel yuhquin oyolpoliuh, oyulçotlahuac.

And [a person from Padua] befriended a wicked person, a deceiver, a soothsayer, one who gazes upon water. And when he summoned the demons, then they came, they came roaring greatly, they came thundering, they came thumping the ground with their feet. And the person, he lost his mind, he fainted from fright.

(6) Sahagún (Reference Sahagún and Anderson1993 [1579]:104–106), Adiciones, Apéndice a la Postilla: y Ejercicio Cotidiano

Auh ynic ontlamantli amimatizque yn ipa[n] yn amonemiliz yn otli…amo no cenca çan namoyollic y[n] ayezque, amo anquihuihuilanazque yn amocxi ynic amo amopan mitoz anvilaxpopol anxocotexpopol, ameticapopol ynic amo amopan mihtoa antlatlaztimintinemj anquiquimichmitinemih, ynic amo ancamanalti amo cuepazque amihtolozque amixiuhcanenemizque amo no anquetzilnenemizq[ue], amo no anxoxotlamatizque, amo anmocuecuelotizque ynic amo amopa[n] mitoz, ca çan antleinpopol, ca ancuecuechme.

Second, you must be prudent in the way you conduct yourself along the road…you really mustn’t creep along, you mustn’t drag your feet so that it won't be said of you: “Big old draggers! Big old leavening agents! Big old dead weights!” [and] so that it won't be said of you that you go around waddling, you go around like mice, so that you don't turn into jokes. It will be said of you that you walk like a pregnant woman. Also don't hurry along on tiptoes, don't act like a firefly, don't go along raising and lowering your head [like a crazy person], so that it won't be said of you: “You big old good-for-nothings! You shameless ones!”

(7) Sermones y ejemplos en mexicano (16th c.:n.p.)

Auh y[n] tlatlacoanime in tlacentelchihualtin. yezque ocel intlaheuliltic […] ca cuicuichecpopol tlaltepopol […] ca nel noço mictlatenamazpopol ye tihui huel aqualnezcapopol temamauhticapopol iyacapopol tlaelxayaquicapopol tlacatecolotlachielicecapopol.

And the sinners, those who are utterly cursed, O how unfortunate they are, […] the big old sooty ones, big old clods of earth! Truly they also go along [like] big-old mictlan hearth-stones. They are big old uglies, big old scaries, big old stinkers, big old excrement-faces, big old human-horned-owl look-alikes.

(8) De contempu[s]omnium vanitatum huius mundi (prior to Reference Rodriguez and Bautista1570:f. 88v)

Oc no centlamantli yn itlayhiyohuiliz yez in yehuantin tlatziuini, in tlatziuhtomacpopol, cuitlatzcopicpopol, cuitlaçotlacpopol, tepoztica quintzopinitinemizque.

And here's another thing regarding what their torments will be, those lazy people, those big lazy fatsos, big careless lazy people, big old slackers: [the demons] will go along pricking them with metal.

MONSTER-CLOWN COMPLEX IN PRE-CONTACT MESOAMERICA

Defining of Terms: Monsters and Clowns

The results of my search for Indigenous examples of physical deformity and transgressive behavior draw together a motley crew of characters and characteristics that I have termed the monster-clown complex. Although the terms “monster” and “clown” are commonly used by scholars, both are problematic in that they carry their own reservoirs of meaning in the Western tradition. Therefore, a clear definition of each is warranted before proceeding any further.

Early European observers of the Americas and its inhabitants frequently described visions of monsters among the Indigenous inhabitants of the land. The chronicles they wrote are filled with stories of people “with two heads but one body” (Lockhart Reference Lockhart1993:56), gentes que no tienen cabezas, sino en los pechos (Alvarado Tezozómoc Reference Alvarado Tezozómoc1987:692), and men who “lacked ears, thumbs, and big toes” (Durán Reference Durán1994:495). These beings, however, were figments of the European imagination, not the Indigenous. Regarding Nahua understandings of “monsters” and “monstrosity,” Echeverría García (Reference Echeverría García2018) has proposed two defining characteristics. First, he states that the monster was any being “that exceeded the limits of the natural,” typically expressed in exaggerated bodily dimensions. He goes on to add that in central Mexico the monster was typically identified by “abundant hairiness and its frizzy consistency” as well as “the absence of any lower limbs, their malformation or their substitution for an object” (Echeverría García Reference Echeverría García2018:335–336). The second quality he associates with monsters is their transgressive nature. He emphasizes the link between transgression and physical deformity, stating that the monster's deformity “alluded to its immorality” (Echeverría García Reference Echeverría García2018:336). He cites studies of pre-contact teteoh (plural of teotl, Nahuatl for “deity”) such as the Cihuateteoh and Tezcatlipoca, who bear the marks of their sexual transgressions in the form of deformed feet and twisted bodies.

These two characteristics of monsters, deformity and transgression, accord with what I have found in my search for material analogous to the descriptions of demons and sinners in the early colonial Nahuatl-Christian sources. I find the term “monster” problematic, however, inescapably linked as it is in the Western imagination with Frankensteins, vampires, and the like. In its place, I propose the Nahuatl term ahtlacatl. In his 1571 Vocabulario, Franciscan friar Alonso de Molina defines ahtlacatl as mal hombre (Online Nahuatl Dictionary 2000–2020). However, the literal meaning of the term is simply “not-person” or “non-human.” While Molina's definition reflects a European, moralizing perspective on the word, a related term, ahtlacacemelleh, strikes closer, I think, to the Indigenous understanding of “not-human.” According to R. Joe Campbell (personal communication 2019), ahtlacacemelleh carries the following range of meanings: “wild; madman; monstrous; one who is perverse; bewildered or foolish; a deformed thing”. This broader field of associations supports the idea that for Nahuas both physical abnormality and transgressive behavior stripped a person of the status of tlacatl (human, person) and rendered them ahtlacatl or ahtlacacemelleh (Echeverría García Reference Echeverría García2013:42). Nahuas associated many different kinds of beings and behaviors with the term ahtlacatl, from dwarfs and cripples to vagabonds, drunks, and ahuianimeh (“ones who indulge in pleasure,” prostitutes). Foreigners could also be ahtlacah (plural of ahtlacatl), people whose “otherness” was described both in terms of disordered behavior and physical abnormalities. Huastec warriors, for example, stood out in Mexica accounts as “wide-headed, broad-headed” people who let their hair “hang over the ear lobes,” descriptions that echo those of demons and sinners cited above (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 10, pp. 185–186). As such, ahtlacatl seems a more suitable, emic term than “monster” to describe this category of Indigenous being or person.

Like monsters, “clowns” constitute a category in need of reimagining, since one cannot help but conjure images of Bozo or Ronald McDonald when confronted by the term. Nevertheless, these contemporary personae—with their clumsy, comic behavior, their enlarged red noses, and outrageous hair—do hint at the ancient association in both Western and Indigenous American traditions of clowning with certain kinds of disordered behavior and physical abnormality. In the European context familiar to the friars of New Spain, clowns were linked to the long tradition of the fool, the jester, and the jongleur, as well as carnival and the burlesque performances of folk theater (Otto Reference Otto2007). Fools were performers whose antics were intended to elicit laughter. Since their performances could often involve burlesque and obscenity, not to mention biting satire and parody, they were frequently the targets of Church efforts to enforce strict moral standards on the masses who so enjoyed their work. New Spain's friars held a low view of such performances and the laughter they elicited, deeming them unseemly at best and blasphemous or diabolical at worst.

Using the term “clown” to describe certain Indigenous Mesoamerican performances which involved humor and laughter risks masking Indigenous phenomena beneath Western concepts. Brylak (Reference Brylak2015:332), in her work on pre-contact Nahua performance genres, notes that no word existed in colonial Nahuatl that approximated the English word for “actor” or “performer,” at least not as these categories are understood in Western usage. In this paper I will adopt one of the possibilities she discusses, the word mahuiltiani. It is derived from the verb, ahuiltia, which Molina defines as dar plazer a otro con algun juego regozijado, o retozar a alguna persona (Online Nahuatl Dictionary 2000–2020). Mahuiltiani, therefore, means someone who engages in such activities. It can, however, also signify one who mocks or makes sport of people. In this way, the word hints at the complex field of Indigenous performances that involved mimicry, humor, mocking play, as well as the trickster figure.

Performers such as these have been referred to as ritual clowns or sacred clowns in the literature. Ritual clowning is a well-documented and world-wide religious phenomenon, some of the best-described examples of which come from the Americas. Ritual clowns are figures who are ambiguous and difficult to classify, but in general they are performers who strive to “reverse and challenge accepted norms…through theatrics,” much of which is received by their respective audiences as humorous (Attardo Reference Attardo2014:646). Although best documented in the America Southwest among Native American tribes such as the Hopi and Zuni, sacred clowning was a pan-Mesoamerican phenomenon as well. In the absence of a precise term to label pre-contact Nahua sacred clowns, I will use mahuiltiani, given its association with mockery, play, and humor. The mahuiltiani, or sacred clown, is the second category in the monster-clown complex that I argue was indexed by early colonial Nahuatl descriptions of demons and sinners.

Ahtlacah (“Monsters”) in Pre-contact Mesoamerica

One of the principle ways pre-contact Mesoamerican ahtlacah manifested their alterity was through physical deformity. Miller and Taube (Reference Miller and Taube1997:75–76) note that fascination with physical abnormalities dates back to the early Formative period. One of the most ancient and ubiquitous examples of this fascination is the dwarf motif and its close cousin, the hunchback. Dwarfism refers to a number of genetic disorders, the most common of which is achondroplasia, or “short-limbed dwarfism.” Achondroplasia results in a host of physical abnormalities, most notably shorter-than-average limbs (which results in the overall small stature of dwarfs), but also including an enlargement of the head (macrocephaly), prominent foreheads, sway back (lordosis), and bowed legs. Another deformity associated with achondroplasia is kyphosis, or hunchback (U.S. National Libraries of Medicine 2019).

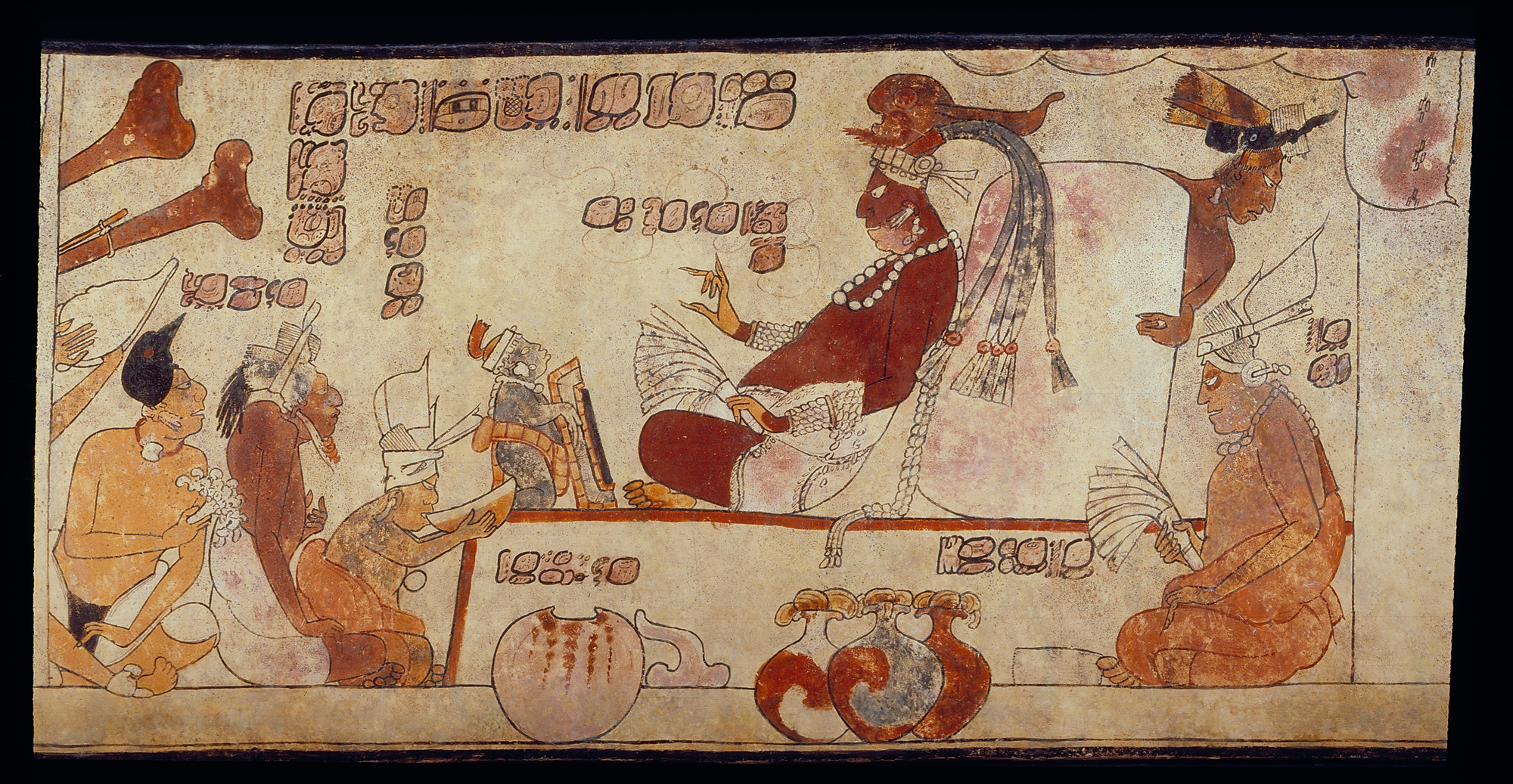

Starting with the Olmec, dwarf and hunchback imagery abounds in Mesoamerican art. Olmec carved stone figurines display a diverse array of human forms that appear to “exceed the limits of the natural,” referring again to Echevarría García's definition of Nahua “monsters,” or ahtlacah (Reference Echeverría García2018:335). At San Lorenzo, Potrero Nuevo Monument 2 shows dwarfs as “skybearers,” supporting the heavenly throne of the king (Taube and Taube Reference Taube, Taube, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009:246). These and other images depict human forms that emphasize their squat stature, short limbs, enlarged heads, distorted facial features, and hunched backs (Figures 1 and 2). During the Maya Classic period, dwarf imagery multiplied, with dwarfs populating carved stone monuments, painted vessels, and appearing in numerous carved or molded clay figurines. Miller (Reference Miller and Benson1980:141) lists the characteristic features of Maya dwarfs as “small stature, abnormally short and fleshy limbs, a protruding abdomen, and a disproportionately-large head with prominent forehead, sunken face, and a drooping lower lip” (Figure 3). In addition to dwarfs, Maya figurines include a number of other types that also demonstrates physical deformities. Among these, Halperin (Reference Halperin2014:99) lists “fat men” (also “fat gods”) who are characterized by “big bellies, hanging jowly cheeks, closed or swollen eyes,” and large lips (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Crouching Figure (Olmec), 10th–4th century b.c. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number: 1979.206.691 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/312878).

Figure 2. Seated Hunchback Holding Mirror (Olmec), 1000–500 b.c. ©The Dallas Museum of Art. Object Number: 1993.81 (https://collections.dma.org/artwork/5070493 ).

Figure 3. Dwarf Figurine (Maya), a.d. 550–850. ©The Walters Art Museum. Accession Number 2009.20.36 (https://art.thewalters.org/detail/80191/dwarf-figurine/).

Figure 4. Costumed Figure (Maya), a.d. 7th–8th century. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number 1979.206.953 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/313151).

In ancient Mesoamerica, dwarfs were closely linked with the royal family, appearing as attendants and entertainers, but also may have been associated with royal lineage, sacrifice, the journey to the underworld, and the Mesoamerican ballgame (Figure 5). “Royal dwarfs” are well documented for the Maya, as the examples above make clear; however, colonial chronicles suggest that the phenomenon was common in the civilizations of central Mexico as well. For example, in his account of Moteuczoma's court, conquistador Díaz del Castillo (Reference Díaz del Castillo and Carrasco2008:168) relates how “sometimes at meal times there were present some very ugly humpbacks, very small of stature and their bodies almost broken in half.” Duran's (Reference Durán1994:295–296) survey of the Mexica tlahtoqueh (pl.; tlahtoani, “ruler”) corroborates this account and contains numerous mentions of “slaves, hunchbacks, and dwarfs” as members of royal households. Durán (Reference Durán1994:307) relates that upon the death of Tizoc in a.d. 1486 “many slaves and hunchbacks and dwarfs were killed, with all the slaves of the king's household, so that not one was left and so they would accompany the king to serve him in the other world,” a statement that hints at a supernatural understanding and function of these special individuals.

Figure 5. Maya ruler attended by a dwarf holding an obsidian mirror. ©Justin Kerr, K1453, Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC.

Dwarfs and hunchbacks were also linked with Mexica teteoh. Muñoz Camargo (Reference Muñoz Camargo1892:154–155) writes of the goddess Xochiquetzal that “in her service there were a large number of dwarves and hunchbacks, scoundrels and vulgar ones, who gave her comfort with great music and dance,” a description of a heavenly retinue that finds parallels in the earthly retinues of the tlahtoqueh described above. In Book 3 of the Florentine Codex, Sahagún's (Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 3, p. 37) informants relate how Quetzalcoatl was accompanied by “the dwarfs, the hunchbacks, his servants.” Another figure associated with Quetzalcoatl was Xolotl, his canine spirit double, or nahualli, who accompanied his master on his journey to the underworld. The word xolotl may be related to xolochoa, “to wrinkle, fold something,” which suggests a semantic field that could index both the effects of age as well as the deformations of achondroplasia, which “folds” bodies over with swayed and hunched backs (Online Nahuatl Dictionary 2000–2020). According to colonial chroniclers like Tezozomoc, dwarfs and hunchbacks were in fact referred to as xolomeh (plural of xolotl; Brylak Reference Brylak2015:108). This usage may perhaps be due to the belief that they, too, would accompany their masters on their journeys to the underworld (Brylak Reference Brylak2015:104); it also alludes to the supernatural power with which certain individuals whose bodies have been “wrinkled or folded” by deformity were endowed.

The evidence reveals a strong link between physical deformity and supernatural beings and powers in Mesoamerican cultures. In particular, physical deformation seems to have been understood to be the result of behavior that transgressed moral boundaries. The Nahua classified certain types of people as “other,” including those Echeverría García (Reference Echeverría García2013, Reference Echeverría García2018) labels “the vagabond,” “the lunatic,” and “the drunkard.” These are people whose actions or behaviors were deemed disordered, excessive, or otherwise transgressing of clearly-stated moral boundaries. It is notable that, in each case, their immoral status was manifest either physically (in deformed bodies) or behaviorally (in disordered behavior). The vagabond is one who abandons the orderly world of the urban center and wanders aimlessly through dangerous, peripheral spaces. In the metaphorical language of the Nahua, he or she has “become a rabbit, become a deer” (in otitochtiac, in otimaçatiac; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 253), a transformation that spoke of the loss of human status (ahtlacatl). The transgressive wanderings of the vagabond could manifest as crooked hands and feet, as illustrated in the Codex Mendoza (Figure 6), or by the chaotic or filthy state suggested by the diphrastic couplet in tzonpachpol, in cuitlanexpol, “big old mossy head, big old ash-colored one” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 243).

Figure 6. Vagabond, from the Codex Mendoza (c. 1541:MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1, fol. 70r). Photograph © Bodleian Libraries.

The lunatic behaves like one who has drunk mixitl, tlapatl, the psychotropic jimson weed and Datura (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 253). In the huehuetlahtolli (“speech of the elders”) recorded by Olmos, the ensuing behavioral display of such a person is described thus: “he beats his neck, he hangs his shoulders, he raises his shoulders, he raises his voice, he shouts…he turns back and forth, he turns around…he screams madly, he calls out loud” (García Quintana Reference García Quintana1974:155). The Florentine Codex describes the behavior of the drunkard using similar language (“he threw himself down, he fell on his face…he went howling and shouting…he chattered, jabbered, gibbered, and mumbled”; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 4, pp. 12, 15) as well as physical transformations of the face (ixchichilpul, “big-old red face,” yxovcpul, “decrepit drunkard's face”), hair (quapopolpol, “big-old twisted hair,” quatzompapol, “big-old matted hair”), and eyes (ixchichilivi, “red-eyed,” yxpupuçaoa, “his eyes were inflamed,” ixtenmjmjlivi, “his eyelids drooped,” ixquatoleeoa, “his eyelids burned”; Figure 7; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982, bk. 4, pp. 11, 13). These brief examples, notable for their repeated deployment of Nahuatl's -pol derogatory suffix, suggest that the ethnographic data collected by Olmos and Sahagún were likely the immediate sources for the descriptions of demons and sinners excerpted above. This makes sense in light of the fact that both ethnographic and doctrinal textual production took place in the scriptoria of New Spain's Franciscan convents and involved the same group of Nahua informants and writers.

Figure 7. Drunk, from the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1575–1577), bk. 4, f. 8v. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Med. Palat. 218–220. Courtesy of MIBACT (Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo).

In addition to the drunks, lunatics, and vagabonds—individuals whose behavior clearly labels them as moral transgressors—the Florentine Codex is replete with instances where vivid language emphasizing bodily transformations can be found. With the assistance of Campbell (personal communication, 2019), I have gathered passages employing Nahuatl's derogatory suffix, -pol, a common lexical denominator in much of the data collected for this paper. There are a number of subject areas where -pol words appear, just the briefest representative examples of which include: descriptions of foreigners: otompol, cuaxoxopol, cuatilacpol, cuexcochchichicapol, otontepol, otompixipol (“you are a miserable Otomí, a green-head, a thick-head, a big tuft of hair over the back of the head, an Otomí blockhead”; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 10, p. 178), descriptions of various kinds of animals: ololpol, catzacpol, yayacpol […] cuitlatolpol, cuitlatolompol (it is round, dirty, dark […] it is very fat, very corpulent,” i.e., a toad; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 10, p. 72), and descriptions of pre-contact gods and rites: texxaxacaltic, tenxaxacalpol, ihuan ixtotolompol (“it had large lips, it had huge lips; and it had big, round, protruding eyes,” i.e., a ritual mask; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 156).

Another highly suggestive passage appears in the well-known description of the teixiptla (deity impersonator) of Tezcatlipoca from Book 2 of the Florentine Codex. Designated for sacrifice at the climax of the high holy day of Toxcatl, the teixiptla was chosen for his perfect physical characteristics. Thus he can be seen as a kind of “manifesto” of Nahua aesthetics. Intriguingly however, he is described primarily in terms of negatives stating what he should not look like. The list produced by the Nahua informants of this passage fills an entire folio (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982: bk. 2, pp. 66–68) and offers one of the most striking parallels to the passages describing demons and sinners cited above. The words used to describe what the perfect human form ought not to look like are some of the very words certain Nahua writers borrowed—and modified with -pol—to describe hideous and sinful beings of the Christian realm. For example, the teixiptla of Tezcatlipoca is described as amo quacocototztic (“not curly-haired”), amo ixquaxitontic (“did not have a forehead like a tomato”), amo ixpopotztic (“not of bulging eye”), amo tencaxtic (“not bowl-lipped”), and amo iacacocoiactic (“he did not have a nose with wide nostrils”; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 2, pp. 66–67). This passage was a rich resource from which writers could mine vivid language, transforming it with the addition of Nahuatl's derogatory suffix, and thereby conjure beings who were the epitome of Nahua views of ugliness and revulsion.

The Florentine's Nahua informants also described transformations of the human form that were not the direct result of moral transgression, but rather due to coming into close contact with more mysterious forces. For example, Sahagún's Nahua informants relate that when one who is weak (cenca auhtic, “very puny”) eats the seeds or ingests the sap of the Teopochotl tree, his or her body swells dramatically. The swelling victim is called nacatica tlamomotlalpol, tlacamimilli, xocopaticapol (“lumpy with flesh, round, an old clod of flesh with two eyes”), is said to have camatalapol, cantetepol, zan huihuiyocpol (“fat cheeks, heavy cheeks, quivering cheeks”), and yacatatamalpol, yacahuiyocpol, yacaololpol (“tamal-like nose, quivering nose, round nose”; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 216). Another example linking physical deformity to contact with some unseen power is found in Book 11's description of the tezcatl, the black obsidian mirror used in divination rituals and associated with the deity Tezcatlipoca. Regarding its magical properties, it was said that in aquin ic motezcahuia, in ompa ommotta camatalapol, ixcuatolmimilpol, tenxipaltotomacpol, camaxacalpol (“when someone uses such a mirror, from it is to be seen a distorted mouth, swollen eyelids, thick lips, a large mouth”; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 228).

Nahuatl-speaking peoples understood physical mutations like those described above as divine punishment for transgression. Two groups of teteoh were responsible for punishing transgressors this way: the five male Macuiltonalequeh (also Ahuiateteoh) and their five female counterparts, the Cihuateteoh. As punishment for excessive drinking, sex, and other kinds of pleasures, these frightening deities would strike the transgressor with various forms of disease, misfortune, and physical deformation. Speaking of the Cihuateteoh, Book 1 of the Florentine Codex records, “When one was under their spell, possessed, one's mouth was twisted, one's face was contorted; one lacked use of a hand; one's feet were misshapen – one's feet were deadened; one's hand trembled; one foamed at the mouth” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 19). Klein (Reference Klein, Klein and Quilter2001:208) notes that “reversed or contorted bodies, limbs, and head often specified sexual misconduct in Colonial-period Nahua manuscript paintings” and cites an illustration of one of the Cihuateteoh in Codex Vaticanus B who is shown her with feet twisted inward.

Bodily deformation was also associated with Tlaloc, the Nahua god of rain, lightning, and storms. Beings called tepictoton were mountain deities considered aspects of Tlaloc. According to Sahagún's informants, they punished those who drank pulque before it was fully prepared, afflicting them with gross bodily disfigurations. In Book 1 we read: “And of him who secretly tasted it, who in secret drink some, even tasting only little, it was said that his mouth would become twisted, it would stretch to one side; to one side his mouth would shift; it would be drawn over” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Dibble and Anderson1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 49). Clendinnen (Reference Clendinnen1991:50) notes that although we tend to find the behavior associated with drunks “no more than irritating or embarrassing,” “for the Mexica it could attract the lightning strike of the sacred.” Inebriation, whether from pulque or through the ingesting of psychotropics, like a murderous rage, or a warrior in the frenzy of battle, or sexual ecstasy, “brought the sacred dangerously near” and therefore required controlling through rigid social norms, punishments, or properly carried-out rituals (Clendinnen Reference Clendinnen1991:51). Twisting of mouths, like the contorting of bodies, marked the transgressor and left them transformed by such “close encounters” with the sacred. Such could also be said of those guilty of looking into the depths of Tezcatlipoca's black obsidian mirror or ingesting the sap of the Teopochotl tree.

Although little understood, it appears that physical deformity in pre-contact Mesoamerica was a condition that marked an individual as somehow special, so much so that kings would keep them close by and society would countenance their sacrifice—often in the form of children—to the gods of rain. It seems likely that dwarfs and others with physical deformities (like the pulque-taster cited above) were thought to have been touched by sacred power, their deformation a visible mark of that awesome and frightening encounter. Such an encounter rendered them liminal beings whose status as human was ambiguous, not-quite-human (ahtlacatl).

Mahuiltianimeh (“Ritual Clowns”) in Pre-contact Mesoamerica

The “royal dwarf” of ancient Mesoamerica lies at the center of the Venn diagram whose outer rings encompass the Indigenous categories of “monsters” and “clowns.” Because of their physical appearance, dwarfs were ahtlacah, beings whose deformation conferred upon them a special status. In their well-documented roles as performers in the courts of the tlahtoqueh, however, they were also mahuiltianimeh, “ones who make fun, who mock, who play,” in other words, ritual clowns. These individuals were both entertainers and important ritual specialists. Their performances were therefore simultaneously profane and sacred, humorous and terrifyingly powerful. Like ahtlacah, ritual clowns were powerful liminal beings who demonstrated their alterity both through physical deformity and what society deemed behavior out of place.

Ritual clowning is a world-wide phenomenon that is particularly well-documented among the Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and North America (Halperin Reference Halperin2014; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1992; Taube Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989; Tedlock Reference Tedlock, Tedlock and Tedlock1975; Wright Reference Wright1994). Ritual clowns operate in sacred contexts, not in the secular ones that are the typical habitat of their European counterparts. Masked and costumed, they engage in the “ritual enactment of reversals,” flipping deeply-ingrained societal concepts like gender roles, sexual norms, political relations, and kinship rules (Attardo Reference Attardo2014:646). Clowns are specially sanctioned to employ ridicule, joking, parody, buffoonery, and juxtaposition—they are taboo breakers and mockers of the powerful whose principal weapon is laughter. Some researchers understand this laughter as providing “psychotherapeutic release” for the audience, while others argue it serves an apotropaic role, and still others note that it marks important moments in the religious and emotional lives of people (Mitchell Reference Mitchell1992:29; Wright Reference Wright1994:x). What is clear is that ritual clowns provide far more than “comic relief,” and are in fact regarded as very powerful individuals.

In the Mesoamerican context, pre-contact ritual clowning is best documented among the Maya. Taube (Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989) employs the terms “festival humor” and “ceremonial jesting” due to the association of the phenomenon of humor with major annual religious rituals. Festival humor involving mocking, joking, and burlesque were forms of “symbolic inversion” that aimed to reinforce the very structures they targeted. Elsewhere, Taube and Taube (Reference Taube, Taube, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009:246) note that one fundamental function of royal dwarfs, perhaps the most common form of ritual clown in pre-contact Mesoamerica, was to serve as the king's mirror-bearer. This is suggestive of what may have been one of the primary functions of the royal dwarf: to magnify and honor the king as the ideal of physical perfection by way of contrast with the dwarf's anti-ideal of deformity and ugliness. This aspect is vividly illustrated in a polychrome painted vessel (Figure 5). Standing up on the royal dais, we see a royal dwarf holding up an obsidian mirror so that the ruler can gaze upon himself in all his finery. The Olmec figurine depicting a hunchback holding a mirror (Figure 2) suggests that this essential symbolic function of dwarfs and hunchbacks stretches back to the very dawn of Mesoamerican civilization.

Beyond reinforcing the kingly ideal, Taube asserts that Maya ritual clowns played key roles in rituals marking critical transitional moments in the calendar (such as the nameless Wayeb’ days) or in matters of royal succession. These were moments of uncertainty and danger which would surely have aroused anxiety among rulers. Although we do not know precisely how humorous ritual performances functioned in the Mesoamerican context, the liminal status of ritual clowns and their ability to serve as intermediaries between humans and deities may have endowed them with the powers necessary to ensure peaceful transition from one calendrical cycle or dynasty to the next.

Although best documented for the Maya region, ritual clowning was a pan-Mesoamerican phenomenon. Surveying the material evidence, Taube (Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989) summarizes the main physical traits of pre-contact ritual clowns. He notes that depictions of clowns are characterized by “ugliness, old age, drunkenness, wanton sexuality, animal impersonation, and shabbiness,” are frequently “grotesquely ugly,” “old and wrinkled,” while others are depicted vomiting on themselves while imbibing alcohol by cup or enema (Figures 4 and 5; Taube Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989:377). The similarities between these traits and those described by Halperin, whose survey of Maya figurines was noted above, show how closely Mesoamerican ahtlacah aligned with mahuiltianimeh. Halperin (Reference Halperin2014:107–108) states as much, situating the “old men, “fat men,” “dwarfs,” and “grotesques” in what she calls the “trickster/ritual clowning complex.” Each one of these categories was associated with the Maya royal court and are assumed to be representations of “entertainers, musicians, dancers, buffoons, and assistants” (Halperin Reference Halperin2014:108). Their performative function is highlighted by the fact that many are depicted holding fans and rattles, wearing masks, and donning costumes (Figure 4).

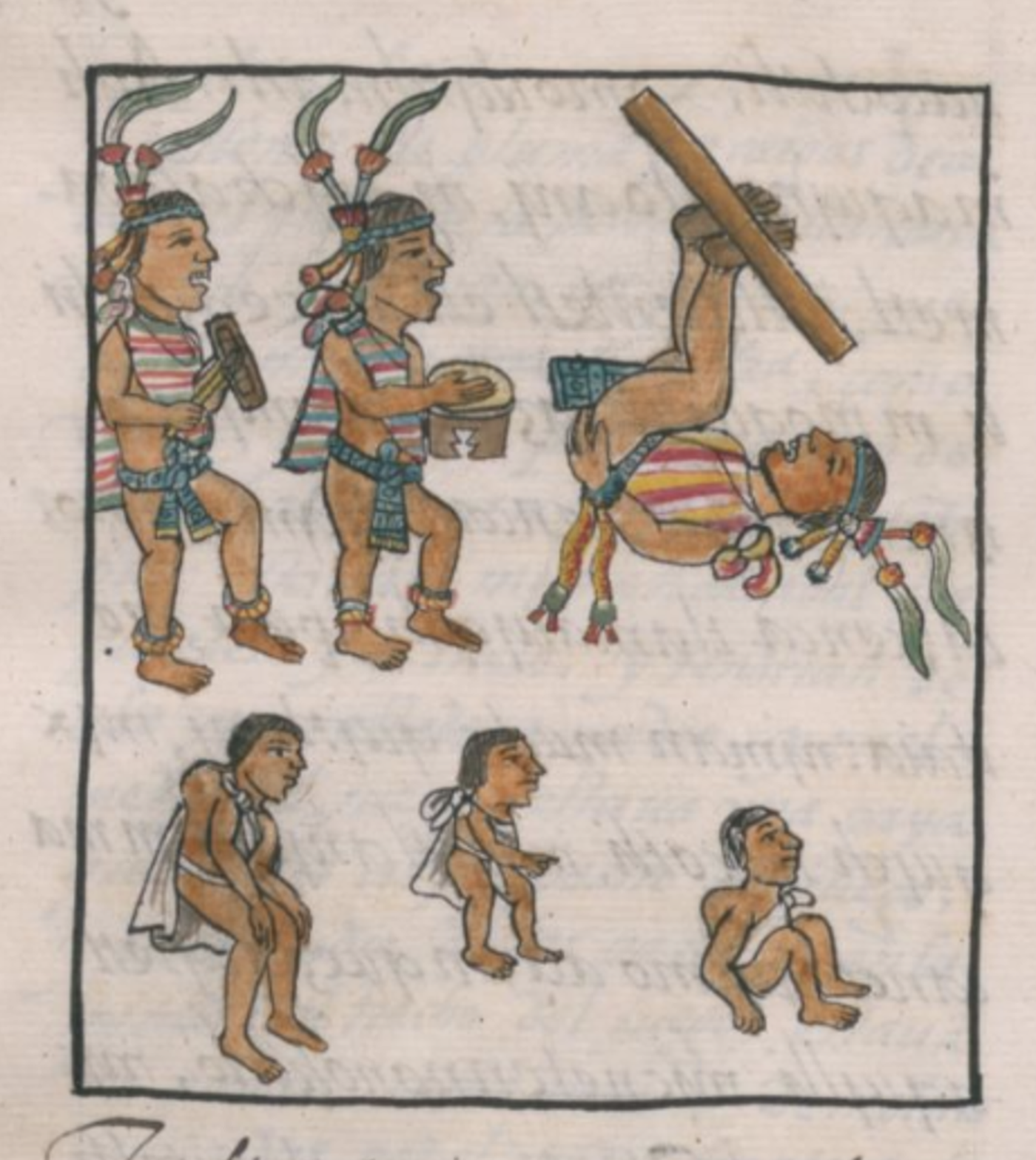

Brylak's (Reference Brylak2015:262) work sheds more light on the form and function of ritual clowning among the Nahua of central Mexico. Spanish observers applied the general concept of “play” (using the word juego) to encompass a very diverse spectrum of cultural phenomena which served as sources of diversion, amusement, and laughter for Nahuas. Among these she lists betting games (netlatlaniliztli), board games (patolli), ballgames (tlachtli), and fake battles. Chroniclers, however, also made note of activities that were more akin to performances. These events they tended to refer to as entremeses, farsas y regocijos de truhanes (Durán Reference Durán2006:vol. 1, p. 257). Torquemada (Reference Torquemada1986:vol. 2, p. 554) describes one such display in the following manner: “One [performer] throwing himself onto his back with his feet raised high, takes a round stick, as long as three rods, and places it on the soles of his feet, turns it and turns it again, throwing it high, and catching it again with the same feet so quickly it is barely visible.” In an illustration from the Florentine Codex that accompanies the description of the same type of entertainment, the artist has included three squat figures in the same frame as the performers, two of whom are clearly hunchbacks, the third a dwarf (Figure 8). This silently attests to the close association of people with these distinctive physical features with performances intended to inspire delight, amusement, and laughter.

Figure 8. Performance with hunchbacks and a dwarf from the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1575–1577), bk. 8, f. 19v. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Med. Palat. 218–220. Courtesy of MIBACT (Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo).

Torquemada (Reference Torquemada1986:vol. 2, p. 554) wrote off these amusing performances as monerías (“monkey business”), but other acts witnessed by Spaniards were viewed in a more sinister light. Various juegos de prestidigitación (“conjuring games”; Brylak Reference Brylak2015:276) and performances involving tiny effigies (what Brylak [Reference Brylak2015:105] calls “puppet shows”) involved forms of magic and divination which the friars condemned as immoral and diabolical. The colonial sources are clear that central Mexican royal courts retained the services of many diverse forms of performers, including those the friars labeled conjurers and sorcerers. But what class of people were they? Were they ritual specialists or merely “entertainers”? Brylak writes that the difficulty we have in answering these questions underscores how little we really understand pre-contact performance and humor. Brylak (Reference Brylak2015:288–289) raises the salient point that whereas non-Indigenous colonial observers made a clear distinction between “entertainment” and “ritual,” no such clear distinction existed in Mesoamerican cultures. The same could be said for the categories of “humor” and “ritual,” categories both deeply implicated in the performances of ritual clowns. The role of play in Nahua culture, like that of humor, was both a means of diversion and a means of opening humans to the sacred power of teotl. Ritual clowns, through their “monerías” and by virtue of their liminal status, performed ritual openings among their audience and played a central role in maintaining the equilibrium of existence that was the general function of Mesoamerican religion.

Based on my research, I argue that Mesoamerican ritual clowns likely all bore some form of physical deformity, that exaggerated facial features (eyes, noses, ears, or lips), deformed heads and disorderly hair, and bodies either shrunken or bent over were integral aspects of what gave the clown its liminal status and endowed it with power. Formative period “skybearers,” Classic Maya “fat men,” and Mexica royal dwarfs attest to the antiquity of this Mesoamerican fascination with individuals bearing the marks of physical deformity, as well as the close association of these individuals with ritual performance and clowning. Colonial ethnographic sources like the Florentine Codex contain the written artifacts of such a tradition, translating the visual culture of the pre-contact era into the new alphabetic system of the colonial world. Early colonial Nahuas who were the writers of Christian texts would have been well aware of this ancient association of deformity with sacred power and clowning; texts like the Florentine Codex and the huehuetlahtolli provided them with a rich lexicon to draw upon, even decades after the voices of the first Nahua informants had faded into the past.

NAHUATL-CHRISTIAN COMIC MONSTERS

The Indigenous bodies and behaviors outlined above overlapped on some level with the friars’ own views of demons and sinners. To European ears, howling and teeth-gnashing were familiar ways to describe the poor souls condemned to hell, as well as the infernal beings who inflicted suffering upon them. Similarly, Euro-Christian demons were marked by bodily deformations which transformed them into frightening, inhuman beings. Some medieval descriptions clearly overlap with the Nahuatl data above and point to European influence. We must, however, not simply register this correspondence and prematurely end our inquiry. To do so would be to fall into the same trap the friars fell into, a trap Lockhart (Reference Lockhart1985:477) has famously dubbed “Double Mistaken Identity.” Regarding the way that early colonial Spaniards and Nahuas understood each other's culture, Lockhart (Reference Lockhart1985) states that each side had the tendency to assume they adequately understood the other's culture, a mistake that was especially tempting when there existed what appeared to be close similarity between the two. He writes that each side manifest “relatively little interest in the other side's internal structure, apparently expecting it in some way to mirror its own.” He continues, stating “the unspoken presumption of sameness showed itself above all in the way each used its own categories in interpreting cultural phenomena of the other” (Lockhart Reference Lockhart1992:445). While similarities between the demons and sinners described above and their European counterparts are evident, if we assume that Nahua authors were merely describing European phenomena using Indigenous terms, we perpetuate the illusion of sameness and remain blind to Mesoamerican cultural forces that may have contributed to shaping how Nahuas understood what was being described. It is necessary to state that it is not the thesis of this article to suggest Nahua descriptions of demons and sinners were utterly novel or universal. Rather, I am interested in exposing what Lockhart (Reference Lockhart1992:445) called the “internal structure” of Mesoamerican thinking about physical deformity and transgressive behavior, and showing that certain Nahua descriptions of demons and sinners indexed cultural phenomena with very different meanings from the European.

In the eyes of the friars, descriptions of demons and sinners that emphasized physical deformity were deemed acceptable since their European analogues were also imagined as grotesque figures whose bodies and behaviors branded them as frightening and “other.” The early friars, however, were likely unaware that in the Indigenous tradition Nahua writers were drawing upon, physical deformity also indexed a host of alternative cultural associations, one of which was ritual clowning. In doing so, three fundamental aspects of the beings referred to in Nahuatl-Christian discourse as tlatlacatecoloh (demons) and tlatlahcoanimeh (sinners) were transformed: their evil constitution, their peripheral status, and their frightening nature. The effects of these transformations fundamentally altered the nature and status of these beings, rendering them comic monsters.

Although demons and sinners could make appearances as comic figures in the medieval context, as far as church teaching was concerned, there was never any question about their status as morally evil beings. Augustine of Hippo (2017) was unequivocal in his lengthy discussion of demons in book 8, chapter 22 of City of God, stating, “we must believe them to be spirits most eager to inflict harm, utterly alien from righteousness, swollen with pride, pale with envy, subtle in deceit.” In medieval hagiographies, demons pursued their efforts to “inflict harm” on the saints of God, even if sometimes their antics could verge on the humorous (Russell Reference Russell1984:155ff.). So, too did the comical machinations of demons in medieval religious theater (Burkhart Reference Burkhart and Trexler2008). In the end, however, saints always triumphed over demons, as good inevitably triumphed over evil in the vast corpus of Christian literature and art that stretches back to earliest times.

In their catechisms and sermons, the friars of New Spain sought to instruct Nahuas in the nature of demons. This was no simple task. While there were Indigenous beings whose appearance and behavior aligned on a superficial level with Christian understandings of demons, one thinks of the Cihuateteoh or Tzitzimimeh, these beings were deities or supernaturals and therefore threatened to undermine the friars’ insistence on the belief in zan huel cen nelli teotl, the “only really one true deity” (Gante Reference Gante1553:f. 69v). Instead, they appropriated a human personage from pre-contact tradition, an Indigenous “sorcerer” in the friars’ perspective, who was understood to be both malicious and dangerously powerful (Burkhart Reference Burkhart1989:40). This personage was the tlacatecolotl, the “human horned owl.” Molina defined this creature as “demonio o diablo” (“demon or devil”), as if merely stating this as fact would make it so in the minds of Indigenous people whose understanding was conditioned by centuries of cultural development (Online Nahuatl Dictionary 2000–2020). Still, it was necessary to be absolutely certain Nahuas understood this being was evil, not merely dangerous. Unfortunately for them, there simply was no synonym for malvado (“evil”). The friars opted for phrases like ahmo cualli (“not good”), an extremely weak surrogate to be sure. Another frequently used word was tlahueliloc. Although Molina defined this as malvado, vellaco (“evil, wicked”), the root of this word is the Nahuatl tlahuelli, which means “rage, fury, or indignation” (Online Nahuatl Dictionary 2000–2020). Here, too, it was clear that conveying the evil nature of demons was doomed from the outset, since none of the surrogates they chose—human horned owls or those described as “furious”—would match closely enough with what they intended. In the absence of clear cultural analogues, friars and their Nahua colleagues resorted to persuasion by description, exploiting the expressive power of the Nahuatl language to create descriptions that would at least frighten Nahuas if not also convince them of the evil status of demons and sinners.

Descriptions such as the one taken from the early seventeenth-century Santoral en mexicano (example 3) are prime examples of this strategy of persuasion by description. As I have argued, however, in addition to indexing European understandings of demons as evil beings, they simultaneously indexed the monster-clown complex, which in turn opened the door to them being rendered comic monsters. Importantly, the comic monster par excellence, the ritual clown of Indigenous American tradition, was not understood to be an evil being. In a broad sense, this was true simply because “good” and “evil” didn't exist as categories in Mesoamerican metaphysics (Maffie Reference Maffie2014:155). What Nahuas called teotl, and the friars inaccurately labeled dios, was the ever-renewing, ever-changing sacred, an impersonal and amoral power that maintained the universe. Both creation and destruction, birth and death, joy and sorrow—categories the friars associated with morally absolute poles of good and evil—were dualities thought of merely as natural and inevitable manifestations of the same oneness of teotl (León-Portilla Reference León-Portilla1963:80–103). For Nahuas, “the basic cosmic conflict was between order and chaos,” not good and evil, and both were deemed essential for the continuation of life as we know it (Burkhart Reference Burkhart1989:35). The “goal” of Nahua spirituality, if it can be spoken of in that way, was not the victory of good over evil, but rather maintaining a balance between the naturally cyclical forces of order and chaos (Burkhart Reference Burkhart1989:47).

In the Mesoamerican tradition, ritual clowns were performers whose humorous antics played a vital role in maintaining balance and order in society. One of the ways they did this was by serving as a foil for the ideal physical and behavioral attributes of the ruler, as previously discussed. Their performances and their very being reinforced dominant societal values through inversion: their physical deformity magnified the ruler's physical perfection; their disordered behavior magnified the ruler's model comportment. By reinforcing these values all of society in turn would benefit from the stability and balance that flowed outward from royal centers of power.

Anthropologists such as Bricker (Reference Bricker1973) and Blaffer (Reference Blaffer1972) argue that modern-day manifestations of ritual clowning strongly suggest that the tradition has deep roots in the pre-contact period, in the Maya region and all across Mesoamerica. Although their studies cannot be taken as direct evidence of colonial attitudes and practices of ritual clowning, they present data which can be seen as constituting the current point on a trajectory that originated in the pre-contact past, remained active in the early contact period, and continued to develop throughout Colonial times. Bricker's (Reference Bricker1973) seminal study Ritual Humor in Highland Chiapas highlights another of the balancing functions of Mesoamerican ritual performers: the lampooning of authority figures such as rulers, priests, and respected elders. According to Bricker, every Christmas season the mayordomos (male religious officials) of Zinacantan assume the roles of ritual humorists called “Grandfathers” and “Grandmothers.” Donning distinctive costumes and masks, they perform a humorous ritual bullfight to the delight of throngs of townspeople, whose enjoyment has augmented by days of drinking. The Grandfathers and Grandmothers engage in lively banter, hurling insults laden with sexual innuendo and eliciting cascades of laughter from the onlookers. Grandmother (who is played by a man) speaks using phrases only elder men use when speaking to younger men, and Grandfather gets “gored” by the “bull” (played by another performer in costume). Together they mockingly enact a bone-setting ritual that parodies the actual prayers offered by Zinacateco bonesetters. The bone-setting impersonator incants: “Stretch out, bone! Stretch out, muscle! Remember your place, bone! Remember your place, muscle!” “Bone” and “muscle” here are references to the penis, just as “place” and “hole” are references to the vagina; the mock bonesetter is of course talking about sex (Bricker Reference Bricker1973:30).

Bricker (Reference Bricker1973:291) notes that, while ritual humor is certainly experienced as entertaining by Zinacantecos, it plays an even more vital role as a means of social control. The antics of the Grandfathers and Grandmothers make stark the contrast between behavior deemed appropriate and inappropriate by the Zinacantecos. The humorous behavior of the Grandmothers reinforces for young girls what kind of behavior their culture expects of women. The same is true for young boys in the audience. Seen from a functionalist perspective, ritual clowns serve to strengthen community norms by mocking them. These kinds of clowning rituals are carried out in Zinacantan over a 13-day period that spans the end of the old year and the beginning of the new. This timing highlights the association of ritual humor with auspicious period endings and beginnings. In his study of Classic Maya humor, Taube (Reference Taube, Hanks and Rice1989:351) argues that ritual humor “marked key periods of transition in the succession of calendrical periods,” such as the five unlucky Wayeb' days at the end of the eighteenth “month” in the haab calendar (Nahuas called this dangerous period at the end of the xiuhpohualli solar calendar the nemontemi.). This period was a time of great uncertainty, a liminal period where cataclysm loomed, kings feared the usurping of their rule, and frightening stellar deities, the Tzitzimimeh, threatened to descend from the sky. Ritual clowns performed important balancing functions, their own liminality and connection with supernatural power perhaps making them especially effective in ensuring a safe transition. In Zinacantan, the climax of the period in which the ritual clowns perform is the ritual “killing” of the “bull.” In Zinacantecan culture, bulls are considered evil, associated with malevolent witchcraft. Bricker (Reference Bricker1973:45) speculates that “through [the bull's] ritual killing and the ceremonial feast which follows the killing, the evil in the community is exorcised every year.”

In early colonial times, when Indigenous audiences had yet to come to terms with the foreign categories of “good and evil,” demons and sinners whose appearance and behavior echoed that of ritual clowns would have been unlikely to have been seen as “evil.” Instead, their deformed bodies and transgressive behavior would have echoed that of powerful liminal beings whose humorous antics were deemed beneficial, ordering forces in times in the ritual year when chaos threatened. Rather than rejecting demons and sinners, as surely was the friars’ intent, their portrayal as Nahuatl-Christian comic monsters instead may have transformed them into beings essential to the maintenance of order and harmony in society during primary moments of transition in the ritual calendar.

Perhaps the most devastating transformation of demons and sinners, at least as far as the mission of the friars went, was the possibility that descriptions like those discussed in this paper rendered these supposedly frightening characters humorous. In his widely-cited discussion of laughter, Bakhtin (Reference Bakhtin1984:90–91) writes that laughter “overcomes fear, for it knows no inhibitions, no limitations.” Laughter represents “victory over the mystic terror of God…the defeat of divine and human power, of authoritarian commandments and prohibitions, of death and punishment after death, hell and all that is more terrifying than the earth itself.” Bakhtin saw in the chaotic and libertine expressions of medieval festival and carnival a subversion of those “authoritarian commandments” and a bold rejection of fear. Of this raucous form of resistance he declared, “the people play with terror and laugh at it; the awesome becomes a ‘comic monster’” (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1984:91). For Bakhtin, the riotous exuberance of carnival-goers was “grotesque” and he associated them with “various deformities, such as protruding bellies, enormous noses, or humps” all of which he deemed suggestive of “pregnancy or procreative power” (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1984:91). The power inherent in this kind of grotesque lay in its ability to transform the frightful into the comic. Laughter gives birth to new possibilities, possibilities that run contrary to the intentions of the powerful.

The friars sought to teach Christianity by frightening Nahuas into rejecting elements of their past deemed “evil” and fleeing into the arms of the merciful Holy Mother Church. Nahua writers collaborated with them and were indispensable cultural intermediaries in the production of the terrifying descriptions of hell and the demons and sinners who inhabited its flame-filled halls. As much as the friars sought to control the narrative of indoctrination, however, Nahua writers drew on language that indexed ancient associations of grotesque physical deformity and boundary-crossing behavior, associations that conjured the clowning dwarfs and “fat men” of the distant Mesoamerican past. By transforming demons and sinners into ritual clowns, the role these frightening characters were intended to play in Nahuatized Christianity was shifted from pitiful foils for the friars’ dogmatizing to important social actors whose ritual activity was central to the maintenance of balance and harmony.

RESUMEN

Durante el período Colonial temprano, los escritores nativos, trabajando con los frailes, compusieron textos cristianos en náhuatl como parte de los esfuerzos de la Iglesia para adoctrinar a la población indígena. Sin embargo, estos “escritores fantasmas” nativos no fueron participantes pasivos en la traducción del cristianismo. Numerosos estudios han demostrado cómo los escritores nativos ejercieron influencia en la presentación del cristianismo, en efecto “indigenizando” el mensaje y permitiendo la persistencia de elementos esenciales de la cosmovisión mesoamericana. Este artículo se enfoca en descripciones de demonios y pecadores extraídos de textos náhuatl-cristianos y argumenta que los escritores nativos se basaron en un antiguo repertorio mesoamericano de imágenes que implican deformidad física y comportamiento transgresor (el “complejo monstruo-payaso”). En tiempos previos al contacto, tales imágenes estaban asociadas con figuras específicas, incluidos enanos olmecas, “dioses gordos” mayas, y artistas cómicos vinculados a la corte real mexica. En cada una de estas figuras, tanto la deformidad física como el humor los convertían en seres liminales poderosos, a menudo denominados “payasos rituales.” Al recurrir a este “complejo monstruo-payaso,” los escritores nativos transformaron lo que pretendían ser motivadores terroríficos de conversión en algo muy diferente: moralmente neutral, sobrenaturalmente poderoso, y miembros esenciales del reino sagrado mesoamericano.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This essay is part of a multi-year project titled “Of Farces and Jesters: Humour and Laughter in Pre-Hispanic and Colonial Nahua Culture from Anthropological Perspective and In the Context of Intercultural Contact (16th–17th Centuries)” directed by Agnieszka Brylak, University of Warsaw. The research leading to the results published here has received funding from the National Science Center, Poland, based on Decision No. DEC-2016/21/D/HS3/02672. The author would also like to express thanks to the participants at the Northeastern Group of Nahuatl Scholars annual meeting in May of 2019 of their collective help with some very difficult Nahuatl words, and to Joe Campbell in particular for his translation assistance, boundless generosity, and friendship. Thanks also to Stephanie Wood, University of Oregon, whose Online Nahuatl Dictionary is an invaluable resource for translators of Nahuatl texts.