Since the 1980s, studies into anxiety have significantly improved the understanding of emotions in language education, contributing significantly to pedagogical innovations. Numerous studies on Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) show that this emotion can be triggered by various factors in and beyond language classrooms, affecting learners’ attainment. Yet, few previous studies in language education endeavored to tackle anxiety in language classrooms from other approaches. One noticeable exception is Shao et al. (Reference Shao, Stockinger, Marsh and Pekrun2023), which approaches anxiety using instruments based on theoretical constructs beyond FLA. Inspired by the emerging education psychology scholarship in epistemic emotions (i.e., emotion related to the generation of knowledge), we attempted to further this endeavor by investigating epistemic anxiety in an ab initio Korean language course. Our results demonstrate that learners’ epistemic anxiety correlates with their perceived value of learning the target language, but it appears to have no significant impact on their intended efforts. Therefore, we further investigated curiosity, another important epistemic emotion, and found it significantly correlates with perceived value and intended efforts. We also found these patterns did not alter between online and offline learning environments. Before discussing the pedagogical implications of these findings, we first review the relevant literature, raise research questions, introduce our methodology, and present the results of our analyses.

Literature Review

Language Learner Emotions: Anxiety and Beyond

In language education, Scovel (Reference Scovel1978) is commonly considered the groundbreaker of research on anxiety. However, research on anxiety did not become mainstream until a decade later, when Horwitz et al. (Reference Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope1986) conceptualized FLA and developed the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS). Since then, anxiety—understood as the learners’ “distress at their inability to be themselves and to connect authentically with other people through the limitation of the new language” (Horwitz, Reference Horwitz, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017, p. 41)—has become the most studied emotion in language education (Sampson, Reference Sampson2022), dominating the landscape of emotions research. During the past decade, particularly under the influence of positive psychology (MacIntyre & Gregersen, Reference MacIntyre and Gregersen2012), a renewed interest has broadened the scope of emotion research in language education (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2022). Consequently, together with anxiety, some positive emotions—such as enjoyment (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014, Reference Dewaele, MacIntyre, MacIntyre, Gregersen and Mercer2016), pride (Ross & Stracke, Reference Ross and Stracke2016), and love (Pavelescu & Petrić, Reference Pavelescu and Petrić2018)—have attracted increasing scholarly attention. Within this context, Plonsky et al. (Reference Plonsky, Sudina and Teimouri2022) noted an expansion of constructs studied in association with emotions, including motivation (MacIntyre & Vincze, Reference MacIntyre and Vincze2017), willingness to communicate (MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Clement, Dörnyei and Noels1998), emotional intelligence (Li et al., Reference Li, Huang and Li2021), grit (Teimouri et al., Reference Teimouri, Plonsky and Tabandeh2020), and flow (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2022).

Although anxiety is widely recognized as a critical emotion in language learning, there has been increasing scrutiny of how scholars approach it. For example, Pavlenko (Reference Pavlenko, Gabrys-Barker and Bielska2013) criticized the overly narrow focus on anxiety in the relevant literature. Similarly, proponents of positive psychology noted that focusing on negative emotions is too reductive (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, MacIntyre, Gregersen and Talbot2018). Additionally, Sampson (Reference Sampson2022) showed that anxiety in language classrooms is low compared to other emotions. Yet, some of the more substantial criticisms of anxiety research in language education are about how it has been measured. FLCAS remains the most used tool to measure anxiety in language classrooms. However, Shao et al. (Reference Shao, Pekrun and Nicholson2019, Reference Shao, Stockinger, Marsh and Pekrun2023) observed that almost one-third of its items seem to not be not directly relevant to anxiety in language learning but instead measure self-efficacy and anxiety outside the classroom. They also noted that the predominant dimension of the scale is related to communicative apprehension, concluding that “FLCAS represents a mix of constructs; it measures more than its name denotes” (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Stockinger, Marsh and Pekrun2023, p. 4). This concern echoes Dewey et al. (Reference Dewey, Belnap and Steffen2018), who reported a small and negative correlation between a FLCAS-based measure and cortisol level. This result problematizes the validity of FLCAS, as cortisol is the primary stress hormone associated with anxiety (Fink, Reference Fink and Fink2016). Likewise, Sparks and Ganschow (Reference Sparks and Ganschow2007) argued that FLCAS probably targets not anxiety but other language-related constructs. In addition, Sparks and Patton (Reference Sparks and Patton2013) voiced concerns about limiting anxiety to the language domain. To sum up, despite its wide adaptation by language education scholars, FLCAS has undeniable limitations in measuring anxiety associated with knowledge generation activities in language classrooms. To bridge this gap, we take on the perspective of epistemic emotions.

Epistemic Emotions: Anxiety and Curiosity

Epistemic emotions have recently started attracting attention from educational psychologists. However, research on these emotions in language education remains underdeveloped. According to educational psychologists, epistemic emotions “result from information-oriented appraisals (i.e., the cognitive component of an emotion) about the alignment or misalignment between new information and existing beliefs, existing knowledge structures, or recently processed information.” (Muis et al., Reference Muis, Chevrier and Singh2018a, p. 169). Therefore, epistemic emotions, such as curiosity, confusion, and frustration, are strictly related to learning and the “knowledge-generating qualities of cognitive activities” (Pekrun et al., Reference Pekrun, Vogl, Muis and Sinatra2017, p. 1268).

Like achievement emotions, epistemic emotions affect learning and outcomes in academic settings, but they also differ from the former in three ways. First, whilst the object focus of achievement emotions lies in the achievement of (or failure to achieve) a goal (Pekrun & Perry, Reference Pekrun, Perry, Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia2014), the object focus of epistemic emotions lies in the generation of knowledge (Vogl et al., Reference Vogl, Pekrun, Murayama and Loderer2019a). For this reason, certain emotions (such as curiosity and confusion) are predominantly epistemic. In contrast, other emotions (such as anxiety and enjoyment) can be either achievement or epistemic, depending on the object focus (Pekrun et al., Reference Pekrun, Vogl, Muis and Sinatra2017). Second, epistemic emotions promote knowledge exploration (Vogl et al., Reference Vogl, Pekrun, Murayama, Loderer and Schubert2019b) and engagement with learning tasks (Chevrier et al., Reference Chevrier, Muis, Trevors, Pekrun and Sinatra2019), affecting learners’ goal setting, motivation, use of metacognitive strategies, and reaching of learning outcomes (Muis et al., Reference Muis, Chevrier and Singh2018a). Finally, although many antecedents (including control, value, novelty, and complexity) are associated with epistemic emotions (Muis et al., Reference Muis, Chevrier and Singh2018a), the essential one is “epistemic incongruity,” which refers to mismatches between new information and background knowledge or beliefs (Chevrier et al., Reference Chevrier, Muis, Trevors, Pekrun and Sinatra2019; Vogl et al., Reference Vogl, Pekrun, Murayama, Loderer and Schubert2019b).

Two epistemic emotions have been studied often. First, epistemic anxiety is a form of doubt arising from “epistemically unsafe” beliefs (Hookway, Reference Hookway, Brun, Doguoglu, Brewer and Cohen2008, p. 61). In academic settings, it is triggered by the misalignment of learners’ beliefs and task content (Trevors et al., Reference Trevors, Muis, Pekrun, Sinatra and Muijselaar2017). Another epistemic emotion often studied with anxiety is curiosity, understood as the “desire for new information aroused by novel, complex, or ambiguous stimuli” (Litman & Jimerson, Reference Litman and Jimerson2004, p. 147). Curiosity is also a form of cognitive deprivation arising from the perception of an information gap, which, therefore, becomes a drive to promote a deeper level of knowledge (Loewenstein, Reference Loewenstein1994). Chevrier et al. (Reference Chevrier, Muis, Trevors, Pekrun and Sinatra2019) found epistemic anxiety to be negatively related to knowledge elaboration, while curiosity promotes learning and self-regulation, which indicates that “curiosity emerged as the most significant epistemic emotion” (p. 15). Muis et al. (Reference Muis, Sinatra, Pekrun, Winne, Trevors, Losenno and Munzar2018b) found that both epistemic anxiety and curiosity can predict critical thinking. They also confirmed that curiosity is triggered by novel and complex tasks when students feel they understand the task and can learn from it. On the other hand, they found that anxiety was triggered when the learner faced information incongruent with their previous knowledge and when learners’ epistemic aim was blocked.

Research on epistemic emotions in educational psychology mainly focuses on investigating learners’ emotional reactions to texts and learning content that may present controversial information or incongruities with learners’ epistemic beliefs, such as content related to climate change (Chevrier et al., Reference Chevrier, Muis, Trevors, Pekrun and Sinatra2019). However, we argue that epistemic emotions such as anxiety and curiosity are also relevant to the language classroom, where students learn language structures, vocabulary, and aspects specific to the target culture that may be in dissonance with their linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Although epistemic emotions remain understudied in language education, their importance is evident. For example, using conversation analysis, Rusk et al. (Reference Rusk, Pörn and Sahlström2016) found that an increase in L2 use in the language classroom posed the risk of generating epistemic discrepancies and restricting the acquisition of L2 conceptual knowledge, such as the meaning of new words. Nakamura et al. (Reference Nakamura, Reinders and Darasawang2022) found curiosity in the language classroom associated with novelty and comprehensibility, while Takkaç Tulga (Reference Tulga2018) argued that it could affect language learners’ linguistic and pragmatic development. Fraschini (Reference Fraschini2023) reported that students in language classrooms experience significantly more curiosity than other emotions, including anxiety. Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy (Reference Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy2019) found a negative correlation between curiosity and FLA, concluding that anxiety may interfere with curiosity in the learning process and that students curious about language learning feel less anxious. Likewise, Hong et al. (Reference Hong, Hwang, Liu and Tai2020) also found a negative correlation between FLA and curiosity, indicating that anxiety may negatively affect the exploration of a foreign language.

Despite their demonstrated importance, language education research has yet to fully explore what emotions like epistemic anxiety and curiosity, in particular, mean for language classrooms. How are these emotions triggered? What are their effects in promoting the exploration of knowledge? We aim to bridge these gaps by investigating how epistemic anxiety and curiosity link learners’ perceived value and intended effort.

Perceived Value and Intended Effort

Value is demonstrated to be a critical antecedent of emotions in academic settings. According to the Control Value Theory of achievement emotions, aspects of the learning environment, including learner-related characteristics, may affect how much a learner feels in control of outcomes and activities and the value they attach to them (Pekrun, Reference Pekrun2006). In other words, learners’ emotional reaction is affected by their perception of control and value. Subsequently, the perceived value was found to be relevant also in the case of epistemic emotions. For example, Palmer (Reference Palmer2018) and Rossing and Long (Reference Rossing and Long1981) found curiosity positively associated with perceived value. Di Leo et al. (Reference Di Leo, Muis, Singh and Psaradellis2019) noted high task value levels related more to curiosity and less to anxiety. Language education researchers have also explored the relationship between learners’ perceived value and anxiety. For example, Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Yang2022) found an increase in anxiety associated with a decrease in intrinsic and attainment values. In this study, we examined whether and how epistemic emotions in language classrooms are affected by students’ perceived value of the language being learned, the learning experience, and the learning activities.

In addition, we also considered the concept of intended efforts to understand whether and how epistemic anxiety and curiosity may promote knowledge exploration in a language-learning setting. Learners’ intended effort has been explored with motivation in language education, but studies sometimes report contrasting results. For example, according to Yashima et al. (Reference Yashima, Nishida and Mizumoto2017), learners with a stronger sense of ideal and ought-to L2 self tend to make more effort in learning the target language. However, Kwok and Carson (Reference Kwok and Carson2018) reported that the ideal L2 self is not a significant predictor of learners’ intended efforts. More recently, Pawlak et al. (Reference Pawlak, Zarrinabadi and Kruk2022) identified several factors of learners’ intended efforts, including the boost effect of negative emotions such as anxiety. Besides, the link between anxiety and intended efforts remains unclear. For example, Shih (Reference Shih2019) did not find any significant relationship between the two, implying that an anxious learner may still put effort into the learning activity.

A further emotion-related construct recently explored in language education that significantly overlaps with intended efforts is grit—perseverance of effort and consistency of interest despite difficulty (Sudina & Plonsky, Reference Sudina and Plonsky2021). Khajavy and Aghaee (Reference Khajavy and Aghaee2022) found perseverance of effort to be a negative predictor of FLA. Similarly, Li and Dewaele (Reference Li and Dewaele2021) also found grit negatively related to anxiety. Besides, anxiety has been reported to be negatively correlated to willingness to communicate (WTC) (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre, Gkonou, Daubney and Dewaele2017), while curiosity is positively correlated (Mahmoodzadeh & Khajavy, Reference Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy2019). These contesting arguments warrant new empirical analysis.

Emotions in Online and Offline Language Learning Settings

Various scholarly efforts have been made to investigate how the online environment impact learner emotions, sometimes with contrasting results. For example, some scholars in educational research claim that leaner emotions differ between online and offline teaching modalities (Butz et al., Reference Butz, Stupnisky and Pekrun2015; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Markus and Gläser-Zikuda2019). Others, however, argue that the effects of leaner emotions are similar between face-to-face and remote classrooms (Daniels & Stupnisky, Reference Daniels and Stupnisky2012; Heckel & Ringeisen, Reference Heckel and Ringeisen2019).

The body of research investigating emotion in online or simply computer-mediated settings is small but growing (Pawlak & Kruk, Reference Pawlak and Kruk2023). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research linking emotions to online language learning modalities was mainly limited to informal digital environments (see, for example, Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yeung and Osburn2022; Lee & Hsieh, Reference Lee and Hsieh2019; Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2020). However, the necessity brought by the COVID-19 pandemic forced teachers and students worldwide to seek alternatives to the offline classroom (Fraschini & Tao, Reference Fraschini and Tao2021; Tao, Reference Tao, Golley, Jaivin and Strange2021a). As a result, researchers started considering how emotions may affect learners in a formal online teaching modality. For example, Resnik and Dewaele (Reference Resnik and Dewaele2021) analyzed a survey comparing students’ online classes with pre-pandemic offline learning, finding that online language learning weakens all positive and negative emotions. However, Resnik et al. (Reference Resnik, Dewaele and Knechtelsdorfer2022) integrated a similar data-gathering technique with qualitative interviews, finding that online learning in an emergency remote teaching situation provided more anxiety-triggering aspects. Dewaele et al. (Reference Dewaele, Albakistani and Ahmed2022) also found that learners in an offline modality experienced significantly more FLA. Yet, they noted that technology-related issues, rather than learning activities, are the main cost of anxiety in the online learning modality. Beyond anxiety, Resnik et al. (Reference Resnik, Moskowitz and Panicacci2021) demonstrated that grit is a reliable predictor of FLA in an online learning environment. In addition, Kruk and Pawlak (Reference Kruk and Pawlak2022) found that curiosity had limited fluctuation across time in a cohort of students learning English in the virtual world of the game Second Life in both informal interactions and the formal virtual language classroom.

Our research intends to continue the existing scholarly efforts to compare language learners’ emotions between the online and offline teaching modalities. However, unlike the studies reviewed above, our research focuses explicitly on epistemic emotions, bridging a gap in the existing literature.

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

This study investigates how epistemic anxiety and curiosity link perceived value and intended efforts in language classrooms from the understudied perspective of epistemic emotions. Furthermore, considering recently observed peculiarities of emotions in online language classrooms, we conducted comparative investigations in both traditional and online teaching modalities. Our research questions are as follows.

RQ1. What is the relationship between epistemic anxiety and curiosity?

RQ2. What is the relationship between learners’ perceived value and intended efforts?

RQ3. What are the effects of perceived value on epistemic anxiety and curiosity?

RQ4. What are the effects of epistemic anxiety and curiosity on learners’ intended efforts?

RQ5. To what extent does the teaching modality (online vs. offline) affect how epistemic anxiety and curiosity link learners’ perceived value and intended efforts?

Methodology

Setting

Data for this study were collected among students enrolled in the ab initio Korean language course at the University of Western Australia (UWA) between February and June 2022. This course is taught across a standard 12-week semester. Students started by learning the Korean script in the first two weeks. They then learned basic grammar structures and how to use the language for communicative purposes across the speaking, reading, listening, and writing domains. The students were allocated to 12 similar-sized tutorial groups, eight of which were taught face-to-face. The remaining four groups were taught entirely online. Four instructors (two Korean L1 and two Korean L2 speakers) rotated between different tutorial groups. Whilst most students stuck to the same tutorial group, some took classes in different modes for various reasons, including the need to comply with COVID isolation regulations.

Each group met twice a week. The first class mainly included grammar-focused exercises, and the second included speaking, reading, and listening activities. Students’ epistemic emotions were measured with specific reference to the activities conducted during the second class. The course coordinator prepared identical teaching materials and lesson plans for all groups to guarantee that all students had similar learning experiences, studied the same language content, and conducted the same classroom activities.

Participants

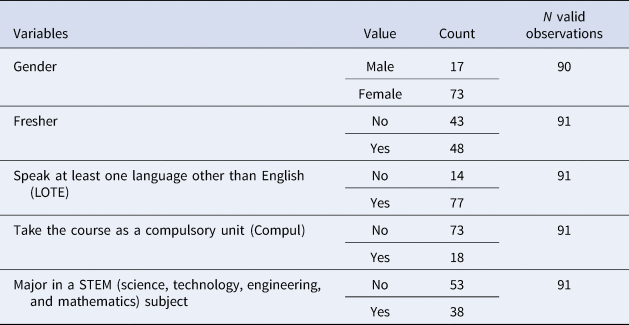

In total, 317 students enrolled in the ab initio Korean course in 2022, among whom 91 students participated in the survey at least once, yielding a participation rate of 28.7%. This sample shares many features of the whole class. For example, as Table 1 shows, the number of females is significantly higher than males, and there were more first-year students than returning students. In addition, most students took this course as an elective. Furthermore, students who majored in a STEM subject (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) counted for 38% of the sample. The rest of the sample consisted of students majoring in arts, business, law, and other non-STEM subjects. Finally, almost 85% of the sample reported that they had previously learned another language, reflecting the institution's multicultural environment and the fact that the course is popular among international students.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Note: Words in parentheses mark respective control variables in the regression tables.

Survey Instrument

The survey used for this study included 21 items, among which eight were used to collect information on learners’ backgrounds, including previous language learning experience, gender, L1, degree area, whether the course is compulsory or optional to the student, and the tutorial group the student attended at the time of the survey. The final item asked whether the class was online and whether a Korean L1 or L2 teacher taught it. In addition, five items, adapted from Wigfield and Eccles (Reference Wigfield and Eccles2000), were used to measure perceived value, and another six were adapted from Yashima et al. (Reference Yashima, Nishida and Mizumoto2017) to measure intended efforts. The consistently high value of Cronbach's alpha, as reported in Table S1 of the supplementary file,Footnote 1 indicates that the survey instruments are reliable. Finally, to measure epistemic anxiety and curiosity, we adapted the two relevant single items in the short version of the epistemically related emotions scales (EES) (Pekrun et al. Reference Pekrun, Vogl, Muis and Sinatra2017). In addition, we customized the instruction to reflect the content of the speaking, reading, and listening activities conducted in the Korean language class that represents the context under investigation.

Data Collection

The same survey was deployed weekly through the course's Learning Management System (LMS) for six consecutive weeks, from week 5 to week 10. After receiving institutional Human Research Ethics approval, students were invited to participate in the survey through a weekly announcement posted on the LMS. In addition, reminders were sent at the end of each week's language class. Each announcement made clear that participation was voluntary. It was also clear that students did not have to commit to all six weekly surveys. At the end of their second weekly class, students were given three to five days to participate in the survey, after which we closed the previous week's survey and opened the same survey for the next week.

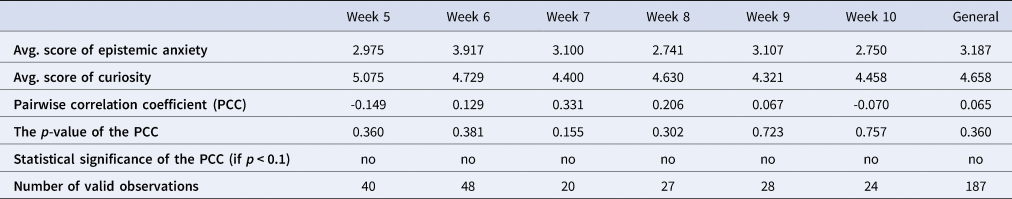

Data Analysis

As shown in the supplementary material, more than half of the participants took the survey only once, and just over a quarter of the participants took the survey three or more times. In addition, according to the weekly average score of epistemic anxiety or curiosity reported in Table 2, there is no significant nor consistent trend in either epistemic emotion over the weeks. The lack of a pattern in the weekly dynamics of both epistemic emotions is further revealed by the boxplots in Section 2 of the supplementary file. Therefore, time is unlikely to be an independent variable that affects epistemic anxiety and curiosity in our research setting. Accordingly, we pooled all data into one set for all regression analyses reported in the next section. However, to prevent our results from being disrupted by unobvious dynamics between weeks, we clustered regression models by weeks where possible and relevant. The regression results of the cluster terms, reported in the supplementary file, further confirm that both epistemic emotions were primarily stable throughout the survey period.

Table 2 The Weekly and General Scores of Epistemic Anxiety and Curiosity

Notes:

1. The epistemic emotions were measured on a 7-point scale between 1 and 7, with 1 indicating not at all and 7 indicating extremely strong.

2. The statistical significance threshold is set at the 10% level. No significance on such a loose threshold indicates that the PCCs are not significant on tighter thresholds, meaning the two emotions are extremely unlikely to be correlated.

Results

Relationship Between Epistemic Anxiety and Curiosity

As demonstrated in Table 2, our statistical results indicate that epistemic anxiety and curiosity are unrelated. These results suggest that L2 learners can simultaneously experience epistemic anxiety and curiosity, as the two emotions are not interdependent. However, it is worth noting that the average level of curiosity was consistently much higher than that of anxiety.

Relationship Between Learners’ Perceived Value and Intended Efforts

Our results confirm that learners’ perceived value positively correlates with their intended efforts. As shown in Table 3, this correlation is significant and stable even after control variables are included and the results are clustered weekly. According to these results, the higher the value a learner attaches to learning the target language, the more likely they intend to make learning efforts. Besides, other things being equal, return students reported a higher level of intended efforts than first-year students, which is consistent with our teaching experience.

Table 3 Regression Results Regarding the Correlation Between Learners’ Perceived Value and Intended Efforts

Notes:

1. Single asterisks (*) indicate coefficients significant at the 10% level. Double asterisks (**) indicate coefficients significant at the 5% level. Triple asterisks (***) indicate coefficients significant at the 1% level.

2. t statistics are reported in parentheses.

3. “L1 Teacher” stands for the class taught by a Korean L1 speaker.

4. The model is clustered by week.

5. Please refer to the supplementary file for (1) completed results of the model above that include coefficients and standard errors for dummy variables of weeks and (2) results of the simpler models without control and/or cluster variables—their results of which are consistent with those reported here.

6. All notes above apply to subsequent tables, which only include additional notes to avoid repetition.

Effect of Perceived Value on Epistemic Anxiety and Curiosity

As reported in Table 4, perceived value correlates with both epistemic anxiety and curiosity but in different ways. On the one hand, perceived value negatively correlates with epistemic anxiety, although the significance level is low when controlling learner and teacher variables. On the other hand, perceived value positively correlates with curiosity, with coefficients and significance levels both stronger than those associated with epistemic anxiety.

Table 4 Regression Results Regarding the Correlations Between Learners’ Perceived Value and Epistemic Emotions

In addition, the results regarding control variables in Table 4 show that male students appeared to be more curious than female students and that, other things being equal, STEM students tend to report a higher level of curiosity. In addition, students tend to experience a lower level of epistemic anxiety and curiosity in classes taught by an L1 speaker. This pattern deserves additional investigation in the future because it indicates that under certain circumstances, epistemic anxiety and curiosity could be affected in the same direction. We also noted that students who took the course as a compulsory unit tended to report lower levels of epistemic anxiety. This pattern confirms our observation that students who take Korean studies as a major or minor tend to be more confident in the ab initio language class.

Effect of Epistemic Anxiety and Curiosity on Learners’ Intended Efforts

According to Table 5, other things being equal, epistemic anxiety does not correlate with intended efforts, whether presented alone or alongside curiosity. On the other hand, curiosity positively correlates with intended efforts, whether presented alone or alongside epistemic anxiety. The fact that no control variable remains significant across all models in Table 5 further highlights curiosity's importance in language classrooms.

Table 5 Regression Results Regarding the Correlations Between Learners’ Epistemic Emotions and Intended Efforts

Effect of the Offline/Online Teaching Modality on Epistemic Emotions and How They Link Learners’ Perceived Value and Intended Efforts

As shown in Table 6, our empirical findings reveal that epistemic emotions and their linking patterns with learners’ perceived value and intended efforts are similar between online and offline teaching modalities. First, according to the results of Models 5a.1 and 5a.2, online and offline learners in our sample appear to experience similar epistemic anxiety and curiosity levels. Second, according to the results of Model 5b, learners’ perceived value correlates with their intended efforts in both online and offline language classrooms. Third, according to the results of Models 5c.1 and 5c.2, the correlations between epistemic emotions and perceived values follow the same pattern in online and offline teaching settings. Finally, according to the results of Models 5d.1, 5d.2, and 5d.3, the patterns of relationships between epistemic emotions and intended efforts do not differentiate between online and offline settings.

Table 6 Regression Results Regarding Whether and How Online/offline Learning Environments Correlate with Epistemic Emotions, Perceived Values, and Intended Efforts

Note: We also conducted regressions with interaction terms between online/offline learning environments and other independent variables, including perceived value and epistemic emotions. The results are consistent with those reported above. Those models are only presented in the supplementary file due to severe multicollinearity, a further sign that online/offline learning environments do not alter the statistical patterns reported in Tables 4 and 5.

Discussion

The analysis of our data collected among university learners enrolled in an ab initio Korean language course shows epistemic anxiety and curiosity to be unrelated. However, previous research in language learning suggested that anxiety (measured by FLCAS) negatively correlates with curiosity, implying that the former may impede the latter (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Hwang, Liu and Tai2020; Mahmoodzadeh & Khajavy, Reference Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy2019). Considering this, we acknowledge that further research in language learning must be conducted to understand the relationship between anxiety and curiosity better. Nevertheless, if we focus on curiosity, our results align with the findings of Kruk and Pawlak (Reference Kruk and Pawlak2022), revealing that language learners experience consistently higher levels of curiosity than negative emotions such as anxiety. In addition, our results complement the few pioneering works on curiosity (e.g., Fraschini, Reference Fraschini2023; Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Reinders and Darasawang2022), further highlighting the necessity of more in-depth studies on curiosity in language classrooms.

Our empirical results confirm that learners’ perceived value and intended efforts are correlated. This correlation is perhaps intuitive for many language educators. However, to promote students’ intended efforts in language classrooms through evidence-based pedagogical innovations based on this correlation, we need to look into the possible intermediate effects of epistemic emotions. Our results show that perceived value correlates positively with curiosity and negatively with epistemic anxiety, demonstrating that the value learners attach to language classroom activities affects their experience of epistemic emotions. These findings are aligned with Di Leo et al. (Reference Di Leo, Muis, Singh and Psaradellis2019) and Pekrun et al. (Reference Pekrun, Vogl, Muis and Sinatra2017), confirming that students who attach a higher value to the learning activity are also likely to be more curious in language classrooms.

Our results show that male learners appear more curious than female learners in language classrooms. However, language education scholars have, thus far, reported no consensus on the correlation between gender and emotions (Botes et al., Reference Botes, Dewaele and Greiff2022). Therefore, subsequent studies must further investigate our results because our sample has a relatively small number of male participants.

Regarding intended efforts, we found it to be correlated with curiosity but not anxiety. This result echoes Shih (Reference Shih2019), indicating that learners who experience epistemic anxiety during classroom activities may still put effort into language learning. Furthermore, the positive correlation between curiosity and intended efforts confirms that curiosity can promote knowledge exploration (Vogl et al., Reference Vogl, Pekrun, Murayama, Loderer and Schubert2019b), learning task engagement (Chevrier et al., Reference Chevrier, Muis, Trevors, Pekrun and Sinatra2019), and WTC (Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy, Reference Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy2019).

Finally, our results show no significant difference regarding episodic anxiety and curiosity between online and offline teaching modalities. This finding contradicts many existing studies, arguing that the online environment is a potential source of more anxiety (Resnik et al., Reference Resnik, Dewaele and Knechtelsdorfer2022) or that emotions are more substantial in offline settings (Dewaele et al., Reference Dewaele, Albakistani and Ahmed2022; Resnik & Dewaele, Reference Resnik and Dewaele2021). A possible explanation of our finding is that the online teaching modality in our study can be only partially categorized as emergency remote teaching, which constituted the environment of previous research. However, not all students in our online classrooms were forced to learn remotely, as many opted in for various reasons and in various patterns. For example, some attended the online lessons for one or a few weeks, while others attended the first tutorial class of the week online and the second tutorial class offline. Moreover, our students were already used to online learning at the time of data collection, thanks to their previous experience during the pandemic. That said, it is worthwhile to conduct subsequent research examining whether our findings hold in other settings because, notwithstanding some excellent pioneering works (Han et al., Reference Han, Huang, Yu and Tsai2021; Trevors et al., Reference Trevors, Muis, Pekrun, Sinatra and Muijselaar2017), epistemic emotions remain severely understudied in the online learning environment.

Concluding Remarks

From the intriguing yet understudied perspective of epistemic emotions, this paper reports the level of epistemic anxiety and curiosity in an ab initio Korean language course and how these two epistemic emotions link learners’ perceived value and intended effort. Our results show that epistemic anxiety and curiosity are independent of each other. They both correlate with learners’ perceived value but in different ways. However, among the two epistemic emotions we studied, only curiosity correlates with the intended effort, suggesting that curiosity is a crucial link between learners’ perceived value and intended effort. We also found these patterns hold in both online and offline learning environments.

These results indicate that epistemic emotions in the language classroom deserve more scholarly attention. Subsequent studies will likely be rewarding by analyzing other epistemic emotions related to the two explored in this paper, including confusion, frustration, and excitement, focusing on how they relate to various language classroom learning activities.

Our findings have two implications for language education. First, students in contemporary higher education institutions can appear instrumentalist, leaving some educators worrying that demanding learning tasks may upset students (Tao, Reference Tao2021b). However, our results, especially the absence of a correlation between learners’ epistemic anxiety and intended effort, mean that educators should feel confident to assign slightly more challenging learning tasks to students, provided these tasks can stimulate their curiosity. Second, our results highlight the importance of curiosity in language classrooms, suggesting that curiosity can significantly affect language knowledge-generating behaviors. Many contemporary universities assign language education to teaching-only faculty members with no or limited workload allocated to their research activities. However, our experience and observations indicate that original research is vital for educators to stimulate learners’ curiosity and evidence-based pedagogical innovations (Tao & Griffith, Reference Tao and Griffith2020). The empirical results reported in this paper further highlight the importance of restoring, maintaining, and strengthening the teaching-research nexus in language classrooms.