Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 November 2011

page 338 note 4 I would like to thank Mr. K. W. Toyne for lending me the cameo while it was in his possession and Mr. G. C. Knowles for help in the preparation of this note.

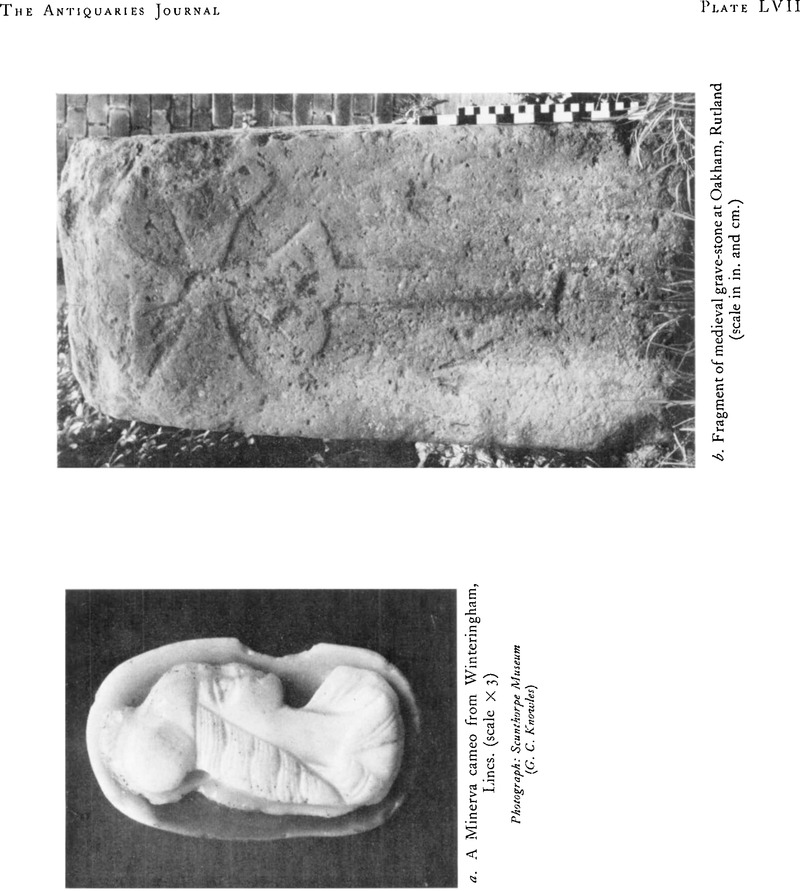

page 338 note 5 Both surfaces have a bluish tinge. Note that the bust is undercut so that it stands out from its background more clearly.

page 339 note 1 Babelon, E., Catalogue des camées antiques et modernes de la Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris, 1897), nos. 17–30Google Scholar. Eichler, F. and Kris, E., Die Kameen im Kunsthistorischen Museum (Vienna, 1927), no. 85Google Scholar. Walters, H. B., Catalogue of Engraved Gems, B.M. (London, 1926), nos. 3441–6Google Scholar. Intaglios are also known; an example engraved on cornelian was found in Canterbury in an Antonine context (information Professor S. S. Frere, F.S.A.), and a jasper ascribed to the first or second century has been published from Charterhouse on Mendip (V.C.H. Somerset i, 43 and fig. 93).

page 339 note 2 Niessen, C. A., Beschreibung römischer Altertümer (Cologne, 1911), no. 5290Google Scholar. Henkel, F., Die romischen Fingerringe der Rheinlande (Berlin, 1913), no. 458Google Scholar. Also note a cameo from Gruissan, Aude, (Gallia xxiv (1966), 453–4Google Scholar, fig. 9), a much finer rendering of the same type. It is slightly larger than the Lincolnshire stone and was presumably set in a brooch.

page 340 note 1 Arch. Anzeiger, lvi (1941), 374–5, fig. 17Google Scholar.

page 340 note 2 I omit an early Byzantine cameo, cut on a garnet and showing a bearded head wearing a Phrygian hat, set in an Anglo-Saxon pendant and found in a garden in Epsom, Surrey, and a possible cameo from Wickham Bushes (V.C.H. Berks, i. 206), about which there is too little information, If it is a cameo it would seem to represent Bonus Eventus, and not ‘Hermes’ as stated.