Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 April 2018

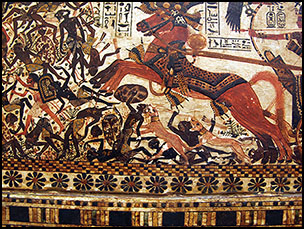

The recent discovery of a well-preserved horse burial at the Third Cataract site of Tombos illuminates the social significance of equids in the Nile Valley. The accompanying funerary assemblage includes one of the earliest securely dated pieces of iron in Africa. The Third Intermediate Period (1050–728 BC) saw the development of the Nubian Kushite state beyond the southern border of Egypt. Analysis of the mortuary and osteological evidence suggests that horses represented symbols of a larger social, political and economic movement, and that the horse gained symbolic meaning in the Nile Valley prior to its adoption by the Kushite elite. This new discovery has important implications for the study of the early Kushite state and the formation of Kushite social identity.