Introduction

Several archaeogenetic and ‘big data’ analyses have recently concluded that the introduction of mining and quarrying practices in Northern Europe at the beginning of Early Neolithic (c. 4000 BC) was related to migration and population change. In these studies, innovations in how flint for toolmaking was extracted from the ground are explained by the rapid expansion of agricultural groups that migrated into Britain and southern Scandinavia from areas in north-western Europe, where mining and quarrying had been practised from c. 4300 BC (e.g. Shennan Reference Shennan2018; Baczkowski Reference Baczkowski2019; Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough2020).

Here, we consider this broad-scale explanation against a local context by examining a selection of human-material relationships related to the introduction of flint extraction in the area around Malmö in south-western Sweden (Figure 1). Using a ‘good-for-thinking’ model (Table 1) that proposes scenarios of transformation by migration, we discuss variation in the ways that transregional practices played out at a local scale during the centuries immediately before and after 4000 BC. We conclude that migration and population change are only part of the explanation for the introduction of flint extraction in the area. Local variations reveal a dynamic interaction between recently introduced human-material relationships and older practices being adapted to change.

Figure 1. Map of the Malmö area, with places mentioned in the text marked. Blue outline = the Södra Sallerup area; black outline = area shown in the historical map in Figure 5; brown line = known extent of the beach ridges. Inset: map of southern Scandinavia with the Malmö area marked (map by Å. Berggren).

Table 1. Scenarios of transformation by migration, related to the potential impact and effect on technology, and social transformation (modified after Högberg Reference Högberg and Brink2015; Furholt Reference Furholt2017).

A ‘good-for-thinking’ model

Robb (Reference Robb2013: 657) encourages us to study the Neolithic “as a set of new human-material relationships which were experimented with” (see also Mithen Reference Mithen2019). Furholt (Reference Furholt2021) demonstrates how such relationships played out with small-scale local and regional impacts, but also with transformative effects on multiple transregional scales. This relates to general theories of migration, which are commonly outlined from either a macro- or a micro-analytical perspective (Castles Reference Castles2010). While macro-approaches refer to large-scale changes in human society, micro-approaches focus on small-scale transformative changes in human social and material lives (Portes Reference Portes2008). Hence, when analysing the complexities involved in human mobility, a conceptual framework for discussing migration in the Neolithic benefits from exploration of transformative processes on the various scales manifested in human-material relationships.

Starting from a model that suggests a selection of potential changes in social transformations related to migration (Table 1), we discuss how groups inhabiting the landscape of south-western Sweden during the centuries either side of 4000 BC had access to and exploited various flint extraction sites. We elaborate on what this means for our understanding of migration and integration of new transregional human-material relationships in a local context. Note that while we roughly use ‘migration’ and ‘mobility’ here as synonyms, no consensus exists on how to define these concepts (see discussion in Burmeister Reference Burmeister2000).

South-western Sweden in the Early Neolithic

Shifting forms of mobility and social interaction related to migration operated at various spatio-temporal scales in south-western Sweden during the late fifth and early fourth millennia BC (Rowley-Conwy Reference Rowley-Conwy2011; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). From the centuries before 4000 BC we have archaeological evidence of transregional contacts, for example objects from continental contexts found in southern Scandinavia (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014). At that time, foraging was the dominant means of subsistence, but variations in material culture on a regional scale indicate the establishment of territorial boundaries and a more sedentary way of life. From the first 200 years of the Early Neolithic—4000 to 3800 BC—we see gradual changes in landscape use, with the introduction of agriculture, farms and large ritual and burial sites (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Artursson and Brink2016). It is not clear how these changes are related to migrating groups, but a few hundred years after we have this first archaeological evidence of agriculture and animal husbandry in south Scandinavia (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Artursson and Brink2016), results from aDNA studies indicate that genetic relationships with farming groups on the Continent and Britain (Malmström et al. Reference Malmström2015; Sánchez-Quinto et al. Reference Sánchez-Quinto2019) existed.

The Malmö area

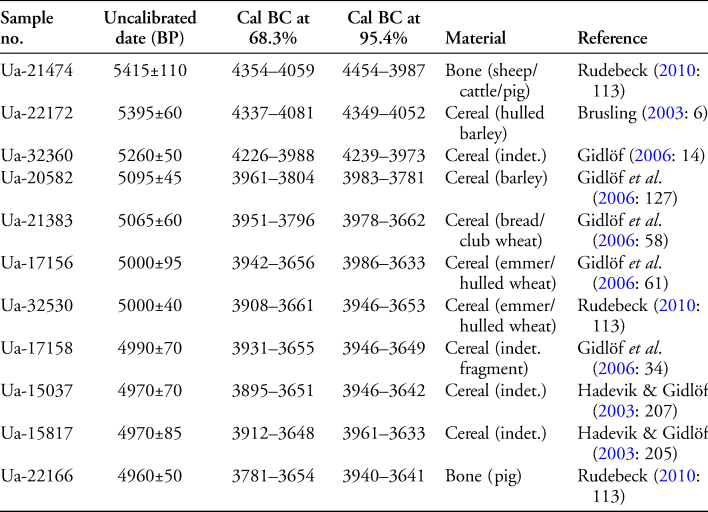

In the area around the city of Malmö in south-western Sweden, more than 45 years of extensive, large-scale contract archaeological excavations have yielded a wealth of prehistoric material that has been systematically investigated and analysed (Nilsson & Rudebeck Reference Nilsson and Rudebeck2010) (Figure 1). The region is a core research area for the southern Scandinavian Early Neolithic (Larsson Reference Larsson2007; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2014; Brink Reference Brink2015; Shennan Reference Shennan2018). Andersson and colleagues, for example, have recently concluded that, here, the landscape was “gradually altered and filled with new meanings in the two first centuries of the EN [Early Neolithic]”, with the Early Neolithic “emerging as a landscape of complex economic and social relations” (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Artursson and Brink2016: 87). Evidence for these changes includes radiocarbon results from the analysis of cereals and domesticated animal bone (Table 2), early indications of the construction of monumental graves, the remains of early post-built structures interpreted as two-aisled houses, and evidence for large sites for gathering and feasting (Berggren Reference Berggren2010; Brink Reference Brink2015; Rudebeck & Macheridis Reference Rudebeck, Macheridis and Brink2015).

Table 2. Selected radiocarbon dates on cereal and bones from domesticated animals from the Malmö area. Dates modelled in OxCal v4.4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2021). Atmospheric data from Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer2020). Indet. = indeterminate.

Local access to and extraction of flint

Early Neolithic groups dwelling in the landscape of the present-day Malmö area had abundant access to flint resources. In-situ limestone outcrops with high-quality Danian-age (c. 66–61.6 Mya) flint were exposed on the surface and along shorelines (Figure 2). In addition, Weichsel glaciation processes created moraine deposits covering the bedrock—deposits containing a variety of flint types, which became accessible where exposed (Högberg & Olausson Reference Högberg and Olausson2007). Although these flint resources were exploited throughout prehistory (Högberg Reference Högberg2009), only two sites, presented below, were quarried for the extensive production of Early Neolithic axehead preforms.

Figure 2. Limestone extraction on the coast of Malmö, from in-situ flint-bearing bedrock (painting by A.T. Fäldt, 1885, in Wickström (Reference Wickström2020, from the cover)); (reproduced courtesy of I. Wickström).

It has been known since the early twentieth century that the area around the village of Södra Sallerup was quarried for flint during prehistory. Slabs of chalk, some several hundred metres long and up to 30m thick, were transported by glacial movement and deposited locally, resulting in the formation of a more than 4.5km long and 700–800m wide area of chalk containing flint of the Senonian age (c. 88.5–65 Mya). From the late 1960s onwards, excavations have systematically documented prehistoric flint mining and quarrying around Södra Sallerup. This work has revealed that flint was extracted by the recurrent digging of pits in locations where chalk was visible on the surface. In areas where glacial moraine deposits overlaid the chalk, mines up to 7m deep were dug (Rudebeck et al. Reference Rudebeck, Olausson, Säfvestad, Weisgerber, Weiner and Slotta1980; Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck, de G. Sieveking and Newcomer1987). Because the chalk does not belong to in-situ bedrock, it is insufficiently stable for the tunnelling of underground shafts or galleries, as was done elsewhere in continental Europe and Britain (Topping Reference Topping2021). Otherwise, the character of flint extraction at Södra Sallerup shows similarities with mining and quarrying in continental Europe; as Shennan (Reference Shennan2018) argues, it is therefore reasonable to consider the introduction of mining and quarrying practices at Södra Sallerup in light of developments in other locations in north-western Europe c. 4000 BC (Wheeler Reference Wheeler and Bossut2006).

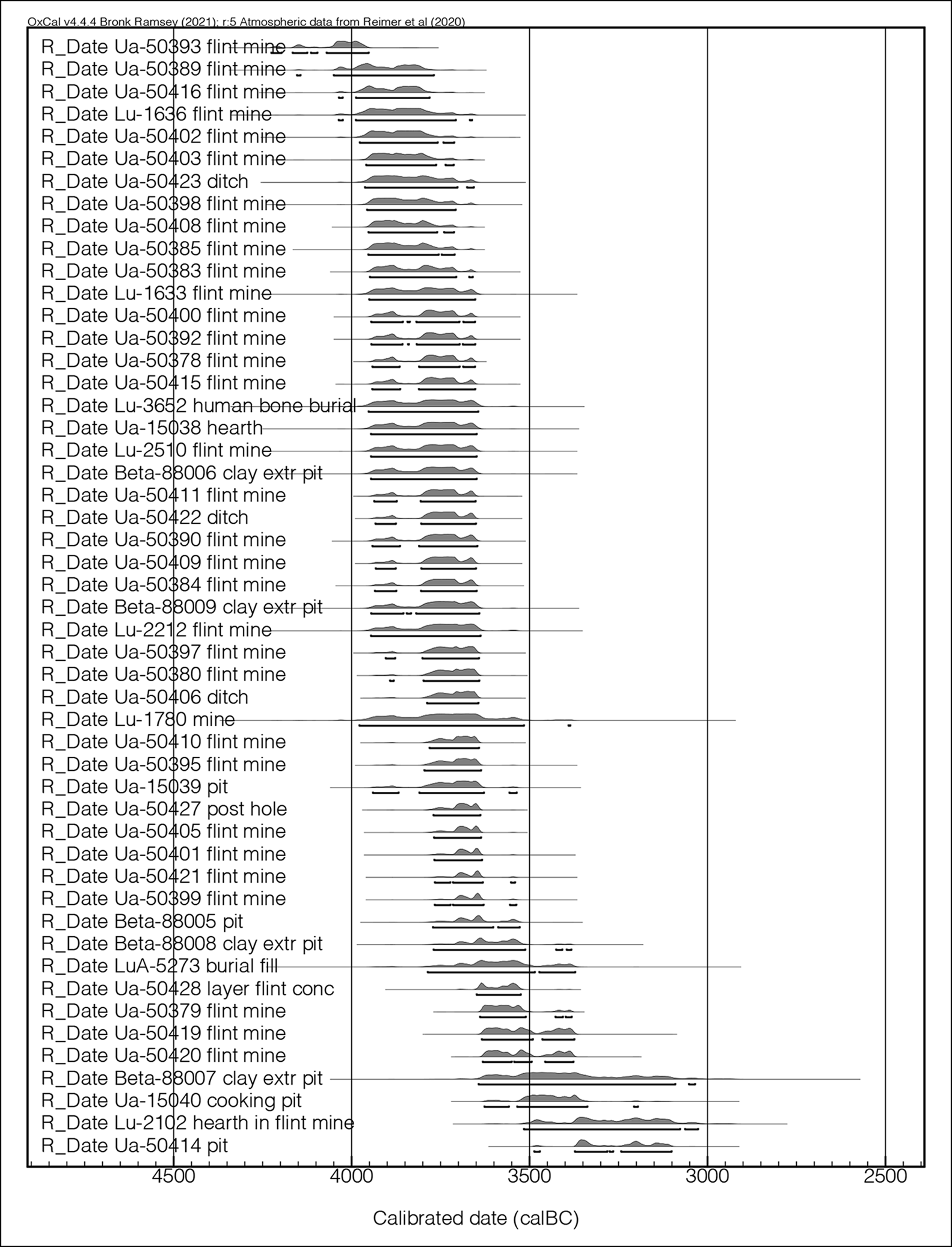

It has been estimated that more than 7000 prehistoric flint mines and quarries were dug in the Södra Sallerup area (Berggren et al. Reference Berggren, Högberg, Olausson and Rudebeck2016), although only a small percentage has been archaeologically documented (Figure 3). Radiocarbon dating of finds from these extraction sites demonstrates a peak in mining and quarrying activities during the Early Neolithic (Berggren Reference Berggren2018) (Figure 4). Although the area was inhabited from an earlier date, there is no known evidence for flint mining or quarrying before 4000 BC at Södra Sallerup (Berggren et al. Reference Berggren, Högberg, Olausson and Rudebeck2016; Berggren Reference Berggren2018; contra Topping Reference Topping2021). Mining was less common during later prehistoric periods but discard piles and older knapping floors were used for raw material extraction up to the Bronze Age (1700–500 BC) (Högberg Reference Högberg2009).

Figure 3. a) Aerial photograph of flint mines in the Södra Sallerup area, 1982 (photograph by L. Wilhelmsson); b) a flint mine under excavation, 2014 (photograph by Å. Berggren).

Figure 4. Results from radiocarbon analysis, showing the main period of flint mining in the Södra Sallerup area (dates calibrated in OxCal v4.4.4, using the IntCal20 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2020; Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2021)).

While mining and quarrying activities at Södra Sallerup are well-known, flint extraction from beach ridges along the coast of the Malmö area has received less attention (Figures 5 & 6). Formed by the Littorina Sea, these ridges consist of gravel and sand, and at several locations there are abundant deposits of flint nodules, which were exploited during prehistory (Högberg Reference Högberg2002). Excavations have revealed shallow pits dug into the beach ridges (Jonsson Reference Jonsson2005). These pits were “bell-shaped […], as a rule about 1m across and about 50cm deep” (Althin Reference Althin1954: 33). It is unclear whether these pits were solely intended for the extraction of flint, as demonstrated in north-eastern Scotland (Saville Reference Saville, Topping and Lynott2005), or whether they also had other purposes. Nonetheless, the analysis shows that the tools used at these beach sites (e.g. core axes, flake axes, blade knifes, transverse arrowheads), as well as associated flakes and debris from tool production, are made of flint sourced from the beach ridges. Radiocarbon dating reveals that these sites were in use during the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic, between approximately 4300 and 3600 BC (Jonsson Reference Jonsson2005). In line with Topping (Reference Topping2021), we see here evidence of Late Mesolithic flint extraction in a region where Early Neolithic flint mining and quarrying activities were introduced c. 4000 BC (see also discussion in Nyland Reference Nyland2016; Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough2021). It is important to emphasise that no earlier evidence of flint extraction is known from south-western Sweden. In contrast to the situation identified elsewhere in Europe (Nyland Reference Nyland2016; Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough2021; Topping Reference Topping2021), flint used for tool production before c. 4300 BC in southern Scandinavia was not mined or quarried but, rather, was collected from the surface, for example along beaches or the banks of streams where flint from limestone bedrock or moraine deposits was exposed (Knarrström Reference Knarrström2001).

Figure 5. Historical map, dated 1702. Beach ridges are marked in the green area east of the shoreline. The yellow linear zone within the green area marks a historical road running north–south along the coast, located on the highest point of the ridges. The light brown area by the coast north of the green beach-ridge area marks a historical zone for extracting in-situ flint-bearing limestone bedrock in open pits. Map originally drawn with south at the top, rotated here by 180° and georeferenced (for scale, see Figure 1) (from Jonsson Reference Jonsson2005: pl. 3, courtesy of Malmö Museum).

Figure 6. Section of the beach ridge in 1957 (photograph from Malmö Museum archive, courtesy of Malmö Museum).

The beach ridges were also used for extensive flint extraction throughout the Neolithic. Within defined areas of the ridges, thousands of preforms for various types of flint axeheads were produced, including Early Neolithic types (Rydbeck Reference Rydbeck1918; Högberg Reference Högberg2002) (Figure 7). These preforms were manufactured using mainly high-quality flint of the Danian age extracted from the beach ridges. The finds were made in the early twentieth century as a result of industrial gravel extraction (Kjellmark Reference Kjellmark1903). As archaeological evidence was destroyed by these modern industrial activities, the nature of the Early Neolithic flint extraction processes at these sites cannot be determined. Several similarly destroyed sites are known from other areas in southern Scandinavia (Högberg Reference Högberg2002).

Figure 7. a) Preforms for point-butted axeheads of flint (see also Rydbeck Reference Rydbeck1918); b) preforms collected in 1995 (photograph by A. Nilsson).

We can therefore conclude that when mining and quarrying were introduced into the area around Södra Sallerup c. 4000 BC, earlier flint extraction sites were already in operation in the region. Hence, at the beginning of the Early Neolithic, we see evidence both of local continuity in the use of sites with a history of flint extraction and the establishment of new mining and quarrying practices. Below, we elaborate on the characteristics of these sites and the flint extracted from them. Our focus here is on the Early Neolithic production of preforms for axeheads, although both informal (expedient) and formal tools were produced at Södra Sallerup and on the beach ridges (Rudebeck et al. Reference Rudebeck, Olausson, Säfvestad, Weisgerber, Weiner and Slotta1980; Jonsson Reference Jonsson2005).

Local production

Burmeister (Reference Burmeister2000) emphasises that variation in technological regimes related to landscape-transforming activities are well suited for the analysis of mobility. Along such lines, Edinborough and colleagues (Reference Edinborough2020) suggest that the introduction of mining and quarrying in Britain was related to the need for high-quality raw material to produce axes designed to clear forests for agricultural activities. Similar arguments have been made for southern Scandinavia, and Sørensen and Karg (Reference Sørensen and Karg2014) show that the distribution of Early Neolithic point-butted axeheads (Figure 8) reflects the early expansion of agrarian settlements. Moreover, the flint mining and quarrying area around Södra Sallerup has been highlighted as a place for the manufacture of preforms for point-butted axeheads (Rudebeck Reference Rudebeck, Edmonds and Richards1998). Results from recent archaeological excavations in the area confirm this production (Berggren Reference Berggren2018). Hence, as in Britain, there appears to be a spatio-temporal correlation here between flint mining and quarrying and Early Neolithic axehead production.

Figure 8. An example of the first type of point-butted axehead (Type I) to appear in the Early Neolithic (photograph by A. Högberg).

The introduction of flint mining and quarrying in the Södra Sallerup area cannot, however, be explained only by a need for high-quality flint for axehead production, as large quantities of high-quality flint were already accessible at the beach ridge sites and, as discussed above, this flint was also used for the production of point-butted axeheads.

An alternative explanation lies in the differences in the types of flint available: at Södra Sallerup, Senonian-age flint was quarried and mined, while at the beach ridge sites, predominantly Danian-age flint was extracted. The character of these two types of flint differs somewhat, with Danian-age flint being coarser (Högberg & Olausson Reference Högberg and Olausson2007). Differences in the treatment of these two types of flint in the production of axeheads have also been identified by Rudebeck (Reference Rudebeck, Edmonds and Richards1998), who notes that small patches of cortex, mainly on the butt-end of the axeheads, are more common on those made of Senonian-age flint than those made of Danian-age flint. These cortex patches could easily have been removed while knapping without altering the shape or affecting the axes’ hafting qualities, but this was not done. Instead, patches of cortex seem to have been deliberately left on the axeheads as a ‘mark of provenance’. Rudebeck (Reference Rudebeck, Edmonds and Richards1998: 326) concluded that flint from the Södra Sallerup area has

been desirable, not only because of the physical qualities of the raw material, but also because of its meaning as a sign of particular events in the social realm […] a sign of the special value attributed to the act of extracting flint.

Studies of the distribution of British Neolithic axeheads have reached similar conclusions (see discussion in Topping Reference Topping2021). Schauer and colleagues (Reference Schauer2020: 836), for example, emphasise that “spatial distributions of prehistoric axeheads cannot be explained merely as the result of uneven resource availability in the landscape, but instead reflect the active favouring of particular sources over known alternatives”. Along similar lines, Topping (Reference Topping2021: 147) concludes that mining and quarrying sites “provided Neolithic communities with ‘socially-valorised’ objects […] emblematic of the origins of the raw material”.

The differences in the ways flint was extracted reflect such discrimination. On the beach ridges, it was possible to extract flint nodules without digging deep into the ground. As Althin (Reference Althin1954) reported, shallow pits dug into the ridges seem to have been sufficient. Caution is required, however, as these sites were discovered more than 100 years ago, without proper archaeological investigation. Nonetheless, there is a considerable difference in the extraction technique used here when compared with the methods for extracting flint at Södra Sallerup, where nodules were excavated from the chalk by digging shafts up to 7m deep.

Rather than linking the introduction of mining and quarrying in the Södra Sallerup area to the need for high-quality raw material for axes, we should perhaps view it as fulfilling a need for axeheads made of the particular type of flint available there. From its history of having been mined and quarried in certain ways at a specific source, the flint from Södra Sallerup carried special meanings to groups using it. Axeheads made of flint extracted from the beach ridges did not carry the same meanings.

Migrating groups?

We return to the model introduced in Table 1 in order to elaborate on flint extraction, the introduction of mining and quarrying in south-western Sweden, and how it might relate to migration and innovation processes.

Gron and Sørensen (Reference Gron and Sørensen2018: 968) define the time between 4400 and 4000 BC as a contact phase, “during which the first signs of the Neolithic emerge” in southern Scandinavia. In south-western Sweden and the Malmö area, flint extracted from beach ridges was already used for tool production some time before 4000 BC. It is possible to see this development as resulting from mobility between groups, in which transregional practices related to flint extraction were introduced from continental Europe to southern Sweden and adopted by existing local populations (scenario A in Table 1). In such a scenario, regional foraging groups may have been influenced to start extracting flint from the ground, as opposed to collecting it from the surface, by agricultural groups inhabiting areas in north-western Europe (see also Jennbert Reference Jennbert1984). Another scenario is that, at the beach ridges some time before 4000 BC, we see evidence of the gradual integration of what is new (flint extraction practices associated with agricultural groups) with what is old (flint extraction practices associated with foraging groups) (scenario B in Table 1). If so, this may represent evidence of migrating individuals introducing the ‘continental’ practice of extracting flint from the ground without changing the local foraging way of life. This is in line with what Hinz (Reference Hinz and Furholt2014: 217) has discussed as the start of “ritual, symbolic or ideological” Neolithic human-material relationships.

Circa 4000 BC, we see a rapid introduction and development of transregional repertoire of human-material practices in the Södra Sallerup area, similar to that seen in Britain (e.g. Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough2020). In light of aDNA research that shows genetic relationships between southern Scandinavian Early Neolithic groups and farming groups in continental Europe and Britain (Malmström et al. Reference Malmström2015; Sánchez-Quinto et al. Reference Sánchez-Quinto2019), it is reasonable to view what occurred in the Södra Sallerup area c. 4000 BC as influenced by the presence of migrating groups. These groups brought with them not only the knowledge and skills required to mine and quarry chalk outcrops, but also a repertoire of human-material relationships related to specific ways of gaining access to flint (Topping Reference Topping2021). The form this mobility took is, however, unclear, as is the local impact that migrating groups had on social transformation processes. The reason for this uncertainty is that, c. 4000 BC, there was also local continuity in the extraction of flint from beach ridges. In a study of raw material extraction sites in Norway, Nyland (Reference Nyland2016) shows that, in some places, the groups who accessed raw material sources before 4000 BC seem to be the same as those that continued to do so after 4000 BC. If, in line with Nyland's results, flint extraction at the beach ridge sites was undertaken by groups which already had a tradition of using these sites, then embodied layers of practice in place for hundreds of years was still expressed at the beach ridges, but for making a new type of axe. If, on the other hand, beach-ridge flint was extracted by groups who had migrated to the area, then older extraction sites were now being used by new groups to produce a new tool type.

Gron and Sørensen (Reference Gron and Sørensen2018: 969) discuss the period between 4000 and 3700 BC as a “negotiation phase”, emphasising that during this phase, regional variation in “both foraging and farming strategies were practised […] with cultural negotiation between populations”. From our study, however, it is unclear whether the practices seen at the beach ridges c. 4000 BC represent:

1) groups associated with those mining and quarrying in the Södra Sallerup area, but who did not have a common repertoire of practice related to the type of flint extracted and the specific ways to access it as in the Södra Sallerup area (scenario C in Table 1);

2) additional migrating groups who adopted flint extraction at the beach ridge sites to produce the same type of axeheads as in the Södra Sallerup area (scenario C or D in Table 1); or

3) groups related to foraging groups who extracted flint from the beach ridges before 4000 BC and were now in the process of ‘becoming Neolithic’ (Mithen Reference Mithen2019), using the same extraction sites as before but producing the same type of axeheads as those produced by the groups in the Södra Sallerup area (scenario B or D in Table 1).

Conclusion

Recently, studies that draw on results from archaeogenetics and big data analysis have related the introduction of Early Neolithic flint extraction practices to migrating groups bringing agriculture into new areas in south-western Sweden. Our results, however, uncover variation in how transregional practices played out on a local scale (for discussion, also see Edinborough et al. Reference Edinborough2021). We see evidence of the introduction of new landscape-transforming activities at c. 4000 BC, which were likely initiated by migrating groups who brought with them certain ways of expressing common repertoires of human-material relationships related to specific ways to access flint, and how this flint was valued. These groups, however, were not the first to extract flint from the ground in the region. This was done before 4000 BC by groups with a foraging way of life. From our results, we cannot determine if these groups continued to extract flint at the same sites as they had before, or if other groups started to use these sites.

Furholt (Reference Furholt2021: 495) recently concluded that the formation of Neolithic lifeways was “a complex process with many locally and regionally distinct histories, in which, from an archaeological point of view, migrants and locals and new and old traditions interacted”. Our study shows similar results. Circa 4000 BC in southwestern Scandinavia, we see both new human-material relationships introduced, and older ones in play adapting to change in various ways. What happened on a transregional scale seems to have played out with its own dynamics on a local scale.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ingemar Wickström for permission to use his image from his fascinating book (Figure 2). We also thank Elisabeth Rudebeck and Liv Nilsson Stutz for constructive comments on an earlier draft and the two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

Funding statement

This article was written as part of the excavation project Pilbladet I, Sydsvensk Arkeologi. The research was partly funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2021-01522).